Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unveiling Extreme Metal Festival Producers

UNVEILING EXTREME METAL FESTIVAL PRODUCERS: THE EMERGENCE OF NARRATIVE IDENTITIES _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science _____________________________________________________ by MARK KLOEPPEL Dr. Grace Yan, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2016 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled: Unveiling Extreme Metal Festival Producers: The Emergence of Narrative Identities Presented by Mark Kloeppel, A candidate for the degree of Master of Science, and herby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Grace Yan, Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism (Chair) David Vaught, Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Timothy Vos, School of Journalism ii Acknowledgements I would like to extend my gratitude and acknowledgement to Grace Yan and the University of Missouri-Columbia Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Department for their guidance in the facilitation of this research opportunity. iii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ -

I Wanna Be Me”

Introduction The Sex Pistols’ “I Wanna Be Me” It gave us an identity. —Tom Petty on Beatlemania Wherever the relevance of speech is at stake, matters become political by definition, for speech is what makes man a political being. —Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition here fortune tellers sometimes read tea leaves as omens of things to come, there are now professionals who scrutinize songs, films, advertisements, and other artifacts of popular culture for what they reveal about the politics and the feel W of daily life at the time of their production. Instead of being consumed, they are historical artifacts to be studied and “read.” Or at least that is a common approach within cultural studies. But dated pop artifacts have another, living function. Throughout much of 1973 and early 1974, several working- class teens from west London’s Shepherd’s Bush district struggled to become a rock band. Like tens of thousands of such groups over the years, they learned to play together by copying older songs that they all liked. For guitarist Steve Jones and drummer Paul Cook, that meant the short, sharp rock songs of London bands like the Small Faces, the Kinks, and the Who. Most of the songs had been hits seven to ten 1 2 Introduction years earlier. They also learned some more current material, much of it associated with the band that succeeded the Small Faces, the brash “lad’s” rock of Rod Stewart’s version of the Faces. Ironically, the Rod Stewart songs they struggled to learn weren’t Rod Stewart songs at all. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

Ouch Podcast

Ouch Talk Show 21 December 2016 bbc.co.uk/ouch Presented by Damon Rose, Beth Rose and Emma Tracey Punk Therapy EMMA Before we get into this week’s episode of Inside Ouch I just want to tell you about an event Ouch will be holding in early 2017. It’s a live storytelling night and the theme is love and relationships. So, if you have a suitable story that you fancy telling in front of a live audience email it to [email protected]. Maybe you’re blind and your partner snogged someone right in front of you at a party. Or maybe your differences make intimacy a little tricky. All we ask is that you are disabled, that the story is true and that it’s about disability in some way. Bookmark bbc.co.uk/ouch/disability for further details. Now, let’s get back into this week’s episode of Inside Ouch. [Music playing – Christmas as a Punk] What do you when you’ve turned 18 or finished formal education if you’ve got learning disabilities? Electric Umbrella sought a solution and wound up with an amazing Christmas single, and they’re here on a quest to make Christmas As A Punk number one. This is Inside Ouch; I’m Emma Tracey in Edinburgh. In London we have Damon Rose. DAMON Hello. EMMA We have Beth Rose. BETH Hi there. EMMA And we have three members of Electric Umbrella. Hello. BAND Hello! EMMA Awesome. So, we’ve got Tom Billington. TOM Hello. EMMA Used to be in Mohair touring with Razorlight and the The Killers. -

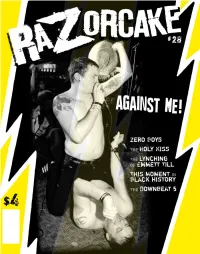

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

At Thirty-Three, My Anger Hasn't Subsided. It's Gotten

t thirty-three, my anger hasn’t subsided. It’s gotten And to all this, I don’t have a real answer. I don’t think I’m naïve. I deeper. It’s more like magma keeping me warm instead of lava don’t think I’m expecting too much, but it’s hard not to feel shat upon by AAshooting haphazardly all over the place. It’s managed. You see, the world-at-large every step of the way. There are a couple of things that I’ve been able to channel the balled-fist, I’m hitting-walls-and-breaking- temper my anger. First off, when we were doing our math, I got another knuckles anger into something of a long-burning fuse. Oh, I’m angry, but number: sixty-four. That’s how many folks help out Razorcake in some I’m probably one of the calmest angry people you’re likely to meet. I take way, shape, or form on a regular basis. Damn, that’s awesome. Sixty- all of my “fuck yous” and edit. I take my “you’ve got to be fucking kid- four people, without whom this zine would just be a hair-brained ding me”s and take pictures and write. I seek revenge by working my ass scheme. off. Anger, coupled with belief, is a powerful motivator. The second element is a little harder to explain. Recently, I was in an What do I have to be angry about? I don’t think it’s obvious, but we do adjacent town, South Pasadena. -

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #19 www.razorcake.com ight around the time we were wrapping up this issue, Todd hours on the subject and brought in visual aids: rare and and I went to West Hollywood to see the Swedish band impossible-to-find records that only I and four other people have RRRandy play. We stood around outside the club, waiting for or ancient punk zines that have moved with me through a dozen the show to start. While we were doing this, two young women apartments. Instead, I just mumbled, “It’s pretty important. I do a came up to us and asked if they could interview us for a project. punk magazine with him.” And I pointed my thumb at Todd. They looked to be about high-school age, and I guess it was for a About an hour and a half later, Randy took the stage. They class project, so we said, “Sure, we’ll do it.” launched into “Dirty Tricks,” ripped right through it, and started I don’t think they had any idea what Razorcake is, or that “Addicts of Communication” without a pause for breath. It was Todd and I are two of the founders of it. unreal. They were so tight, so perfectly in time with each other that They interviewed me first and asked me some basic their songs sounded as immaculate as the recordings. On top of questions: who’s your favorite band? How many shows do you go that, thought, they were going nuts. Jumping around, dancing like to a month? That kind of thing. -

Family Album

1 2 Cover Chris Pic Rigablood Below Fabio Bottelli Pic Rigablood WHAT’S HOT 6 Library 8 Rise Above Dead 10 Jeff Buckley X Every Time I Die 12 Don’t Sweat The Technique BACKSTAGE 14 The Freaks Come Out At Night Editor In Chief/Founder - Andrea Rigano Converge Art Director - Alexandra Romano, [email protected] 16 Managing Director - Luca Burato, [email protected] 22 Moz Executive Producer - Mat The Cat E Dio Inventò... Editing - Silvia Rapisarda 26 Photo Editor - Rigablood 30 Lemmy - Motorhead Translations - Alessandra Meneghello 32 Nine Pound Hammer Photographers - Luca Benedet, Mattia Cabani, Lance 404, Marco Marzocchi, 34 Saturno Buttò Alex Ruffini, Federico Vezzoli, Augusto Lucati, Mirko Bettini, Not A Wonder Miss Chain And The Broken Heels - Tour Report Boy, Lauren Martinez, 38 42 The Secret Illustrations - Marcello Crescenzi/Rise Above 45 Jacopo Toniolo Contributors - Milo Bandini, Maurice Bellotti/Poison For Souls, Marco Capelli, 50 Conkster Marco De Stefano, Paola Dal Bosco, Giangiacomo De Stefano, Flavio Ignelzi, Brixia Assault Fra, Martina Lavarda, Andrea Mazzoli, Eros Pasi, Alex ‘Wizo’, Marco ‘X-Man’ 58 Xodo, Gonz, Davide Penzo, Jordan Buckley, Alberto Zannier, Michele & Ross 62 Family Album ‘Banda Conkster’, Ozzy, Alessandro Doni, Giulio, Martino Cantele 66 Zucka Vs Tutti Stampa - Tipografia Nuova Jolly 68 Violator Vs Fueled By Fire viale Industria 28 Dear Landlord 35030 Rubano (PD) 72 76 Lagwagon Salad Days Magazine è una rivista registrata presso il Tribunale di Vicenza, Go Getters N. 1221 del 04/03/2010. 80 81 Summer Jamboree Get in touch - www.saladdaysmag.com Adidas X Revelation Records [email protected] 84 facebook.com/saladdaysmag 88 Highlights twitter.com/SaladDays_it 92 Saints And Sinners L’editore è a disposizione di tutti gli interessati nel collaborare 94 Stokin’ The Neighbourhood con testi immagini. -

Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate If Seminar And/Or Writing II Course

MUSIC HISTORY 13 PAGE 1 of 14 MUSIC HISTORY 13 General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Music History 13 Course Title Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice x Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis • Social Analysis x Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This course falls into social analysis and visual and performance arts analysis and practice because it shows how punk, as a subculture, has influenced alternative economic practices, led to political mobilization, and challenged social norms. This course situates the activity of listening to punk music in its broader cultural ideologies, such as the DIY (do-it-yourself) ideal, which includes nontraditional musical pedagogy and composition, cooperatively owned performance venues, and underground distribution and circulation practices. Students learn to analyze punk subculture as an alternative social formation and how punk productions confront and are times co-opted by capitalistic logic and normative economic, political and social arrangements. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Jessica Schwartz, Assistant Professor Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes x No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs 2 4. -

Festival 30000 LP SERIES 1961-1989

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS FESTIVAL 30,000 LP SERIES 1961-1989 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER AUGUST 2020 Festival 30,000 LP series FESTIVAL LP LABEL ABBREVIATIONS, 1961 TO 1973 AML, SAML, SML, SAM A&M SINL INFINITY SODL A&M - ODE SITFL INTERFUSION SASL A&M - SUSSEX SIVL INVICTUS SARL AMARET SIL ISLAND ML, SML AMPAR, ABC PARAMOUNT, KL KOMMOTION GRAND AWARD LL LEEDON SAT, SATAL ATA SLHL LEE HAZLEWOOD INTERNATIONAL AL, SAL ATLANTIC LYL, SLYL, SLY LIBERTY SAVL AVCO EMBASSY DL LINDA LEE SBNL BANNER SML, SMML METROMEDIA BCL, SBCL BARCLAY PL, SPL MONUMENT BBC BBC MRL MUSHROOM SBTL BLUE THUMB SPGL PAGE ONE BL BRUNSWICK PML, SPML PARAMOUNT CBYL, SCBYL CARNABY SPFL PENNY FARTHING SCHL CHART PJL, SPJL PROJECT 3 SCYL CHRYSALIS RGL REG GRUNDY MCL CLARION RL REX NDL, SNDL, SNC COMMAND JL, SJL SCEPTER SCUL COMMONWEALTH UNITED SKL STAX CML, CML, CMC CONCERT-DISC SBL STEADY CL, SCL CORAL NL, SNL SUN DDL, SDDL DAFFODIL QL, SQL SUNSHINE SDJL DJM EL, SEL SPIN ZL, SZL DOT TRL, STRL TOP RANK DML, SDML DU MONDE TAL, STAL TRANSATLANTIC SDRL DURIUM TL, STL 20TH CENTURY-FOX EL EMBER UAL, SUAL, SUL UNITED ARTISTS EC, SEC, EL, SEL EVEREST SVHL VIOLETS HOLIDAY SFYL FANTASY VL VOCALION DL, SDL FESTIVAL SVL VOGUE FC FESTIVAL APL VOX FL, SFL FESTIVAL WA WALLIS GNPL, SGNPL GNP CRESCENDO APC, WC, SWC WESTMINSTER HVL, SHVL HISPAVOX SWWL WHITE WHALE SHWL HOT WAX IRL, SIRL IMPERIAL IL IMPULSE 2 Festival 30,000 LP series FL 30,001 THE BEST OF THE TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS, RECORD 1 TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS FL 30,002 THE BEST OF THE TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS, RECORD 2 TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS SFL 930,003 BRAZAN BRASS HENRY JEROME ORCHESTRA SEC 930,004 THE LITTLE TRAIN OF THE CAIPIRA LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SFL 930,005 CONCERTO FLAMENCO VINCENTE GOMEZ SFL 930,006 IRISH SING-ALONG BILL SHEPHERD SINGERS FL 30,007 FACE TO FACE, RECORD 1 INTERVIEWS BY PETE MARTIN FL 30,008 FACE TO FACE, RECORD 2 INTERVIEWS BY PETE MARTIN SCL 930,009 LIBERACE AT THE PALLADIUM LIBERACE RL 30,010 RENDEZVOUS WITH NOELINE BATLEY AUS NOELEEN BATLEY 6.61 30,011 30,012 RL 30,013 MORIAH COLLEGE JUNIOR CHOIR AUS ARR. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

SUBCULTURE: the MEANING of STYLE with Laughter in the Record-Office of the Station, and the Police ‘Smelling of Garlic, Sweat and Oil, But

DICK HEBDIGE SUBCULTURE THE MEANING OF STYLE LONDON AND NEW YORK INTRODUCTION: SUBCULTURE AND STYLE I managed to get about twenty photographs, and with bits of chewed bread I pasted them on the back of the cardboard sheet of regulations that hangs on the wall. Some are pinned up with bits of brass wire which the foreman brings me and on which I have to string coloured glass beads. Using the same beads with which the prisoners next door make funeral wreaths, I have made star-shaped frames for the most purely criminal. In the evening, as you open your window to the street, I turn the back of the regulation sheet towards me. Smiles and sneers, alike inexorable, enter me by all the holes I offer. They watch over my little routines. (Genet, 1966a) N the opening pages of The Thief’s Journal, Jean Genet describes how a tube of vaseline, found in his Ipossession, is confiscated by the Spanish police during a raid. This ‘dirty, wretched object’, proclaiming his homosexuality to the world, becomes for Genet a kind of guarantee - ‘the sign of a secret grace which was soon to save me from contempt’. The discovery of the vaseline is greeted 2 SUBCULTURE: THE MEANING OF STYLE with laughter in the record-office of the station, and the police ‘smelling of garlic, sweat and oil, but . strong in their moral assurance’ subject Genet to a tirade of hostile innuendo. The author joins in the laughter too (‘though painfully’) but later, in his cell, ‘the image of the tube of vaseline never left me’.