Some Murder Ballads and Poems Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Petr Husseini Nick Cave’s Lyrics in Official and Amateur Czech Translations Master‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Renata Kamenická, Ph.D. 2009 Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. .................................................. Author‟s signature 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Renata Kamenická, Ph.D., for her kind help, support and valuable advice. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 1. Translation of Lyrics and Poetry .............................................................................. 9 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 9 1.2 General Nature of Lyrics and Poetry ........................................................ 11 1.3 Tradition of Lyrics Translated into Czech ............................................... 17 1.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................... 20 2. Nick Cave’s Lyrics in King Ink and King Ink II ................................................... 22 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 22 -

A Message to MTV

textploitationtefl A message to MTV Do you know anything about these people? What do you think they might do? (try to use some of the language below) Target language He might be / she could be … He looks like a … I guess she is probably a … They both look as if they are … Listening 1 – Gist Listen and answer the following questions 1. Who is the letter to? 2. What is the letter about? 3. What is he grateful for? 4. What does the writer ask for? 5. What does the writer say he feels unhappy with? Listening 2 – Vocab building Which words complete these phrases? Listen to check nominations I have ________ feel more ________ with ________ appreciated I have always been of the ________ my ________ thanks at the ________ of times ________ said that, glittering ________ textploitationtefl Listening 3 - Attitude Listen again and decide how you think the reader, Kylie, feels about the letter? a) Serious c) Amused b) Concerned d) Happy Reflection What do you think of this decision? Why might other musicians want to take part in awards shows and ceremonies? Should the arts in general be evaluated by competition and prizes? (why/why not) Writing "My muse is not a horse and I am in no horse race." 1. What is the register of the letter you have just heard, formal or informal? Why? 2. Now read the letter on the next page, are there any words which would be typically formal? _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ 3. What typical features of a formal letter are there in this letter? 4. -

Repor 1 Resumes

REPOR 1RESUMES ED 018 277 PS 000 871 TEACHING GENERAL MUSIC, A RESOURCE HANDBOOK FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. BY- SAETVEIT, JOSEPH G. AND OTHERS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPT., ALBANY PUB DATE 66 EDRS PRICEMF$0.75 HC -$7.52 186P. DESCRIPTORS *MUSIC EDUCATION, *PROGRAM CONTENT, *COURSE ORGANIZATION, UNIT PLAN, *GRADE 7, *GRADE 8, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS; BIBLIOGRAPHIES, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, NEW YORK, THIS HANDBOOK PRESENTS SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING CONTENT, METHODS, AND MATERIALS APPROPRIATE FOR USE IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM IN GENERAL MUSIC FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. TWENTY -FIVE TEACHING UNITS ARE PROVIDED AND ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ADAPTATION TO MEET SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS. THE TEACHING UNITS ARE GROUPED UNDER THE GENERAL TOPIC HEADINGS OF(1) ELEMENTS OF MUSIC,(2) THE SCIENCE OF SOUND,(3) MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS,(4) AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC, (5) MUSIC IN NEW YORK STATE,(6) MUSIC OF THE THEATER,(7) MUSIC FOR INSTRUMENTAL GROUPS,(8) OPERA,(9) MUSIC OF OTHER CULTURES, AND (10) HISTORICAL PERIODS IN MUSIC. THE PRESENTATION OF EACH UNIT CONSISTS OF SUGGESTIONS FOR (1) SETTING THE STAGE' (2) INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION,(3) INITIAL MUSICAL EXPERIENCES,(4) DISCUSSION AND DEMONSTRATION, (5) APPLICATION OF SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDINGS,(6) RELATED PUPIL ACTIVITIES, AND(7) CULMINATING CLASS ACTIVITY (WHERE APPROPRIATE). SUITABLE PERFORMANCE LITERATURE, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE CITED FOR USE WITH EACH OF THE UNITS. SEVEN EXTENSIVE BE.LIOGRAPHIES ARE INCLUDED' AND SOURCES OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRIES, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE LISTED. (JS) ,; \\',,N.k-*:V:.`.$',,N,':;:''-,",.;,1,4 / , .; s" r . ....,,'IA, '','''N,-'0%')',", ' '4' ,,?.',At.: \.,:,, - ',,,' :.'v.'',A''''',:'- :*,''''.:':1;,- s - 0,- - 41tl,-''''s"-,-N 'Ai -OeC...1%.3k.±..... -,'rik,,I.k4,-.&,- ,',V,,kW...4- ,ILt'," s','.:- ,..' 0,4'',A;:`,..,""k --'' .',''.- '' ''-. -

Adapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire for the Classical Guitar

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2015 Adapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire for the Classical Guitar Andrew Rhinehart University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rhinehart, Andrew, "Adapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire for the Classical Guitar" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 44. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/44 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, Day Department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 Points)

The elective discipline «INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, day department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 points) Task: Select one British folk ballad from the list below, write your name, perform your individual scientific research paper in writing according to the given scheme and hand your work in to the teacher: Titles of British Folk Ballads Students’ Surnames 1. № 58: “Sir Patrick Spens” 2. № 13: “Edward” 3. № 84: “Bonny Barbara Allen” 4. № 12: “Lord Randal” 5. № 169:“Johnie Armstrong” 6. № 243: “James Harris” / “The Daemon Lover” 7. № 173: “Mary Hamilton” 8. № 94: “Young Waters” 9. № 73:“Lord Thomas and Annet” 10. № 95:“The Maid Freed from Gallows” 11. № 162: “The Hunting of the Cheviot” 12. № 157 “Gude Wallace” 13. № 161: “The Battle of Otterburn” 14. № 54: “The Cherry-Tree Carol” 15. № 55: “The Carnal and the Crane” 16. № 65: “Lady Maisry” 17. № 77: “Sweet William's Ghost” 18. № 185: “Dick o the Cow” 19. № 186: “Kinmont Willie” 20. № 187: “Jock o the Side” 21. №192: “The Lochmaben Harper” 22. № 210: “Bonnie James Campbell” 23. № 37 “Thomas The Rhymer” 24. № 178: “Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon” 25. № 275: “Get Up and Bar the Door” 26. № 278: “The Farmer's Curst Wife” 27. № 279: “The Jolly Beggar” 28. № 167: “Sir Andrew Barton” 29. № 286: “The Sweet Trinity” / “The Golden Vanity” 30. № 1: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” 31. № 31: “The Marriage of Sir Gawain” 32. № 154: “A True Tale of Robin Hood” N.B. You can find the text of the selected British folk ballad in the five-volume edition “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads: five volumes / [edited by Francis James Child]. -

Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog 2003-2004 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog Kentucky Library - Serials 2003 Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog 2003-2004 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ky_hum_council_cat Part of the Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog 2003-2004" (2003). Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog. Paper 5. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ky_hum_council_cat/5 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V - ^• ,.:»-?r: - y,• 1.' t JJ •'•^1 Ba ni'l^Tlnll iui imnmthh^ ¥ mm fa. f*i '• yi-^\ WHOLE HUMANITIES CATALOG August 1, 2003-July 31, 2004 This edition of the Whole Humanities Catalog—the eighteenth—is your comprehensive source for the Kentucky Humanities Council's unique statewide programs. What's your pleasure? Speakers who deftly combine scholarly insights with revealing anecdotes? Kentucky writers discussing their works? A fascinating figure from Kentucky's past brought backto life by our living historyprogram (thereare five newcharacters this year)? Or maybe a book discussion program? There is truly somethingherefor everyone. It is only with your generous and continuing support that weareableto enrich this catalog with morequalityprograms every year. Thank you, and enjoy! Contents Credits Speakers Bureau Featured Speakers 3 Kentucky Writers 15 More Speakers 18 Speakers BureauTravel Map 19 Kentucky Chautauqua 20 Book Discussions 26 Appiication Instructions 28 Application Forms Inside Back Cover www.kyhumanities.org You'll tliid this catalog and much more on our web site. -

Vulnerable Victims: Homicide of Older People

Research and Issues NUMBER 12 • OCTOBER 2013 Vulnerable victims: homicide of older people This Research and Issues Paper reviews published literature about suspected homicide of older people, to assist in the investigation of these crimes by Crime and Misconduct Commission (CMC) or police investigators. The paper includes information about victim vulnerabilities, nature of the offences, characteristics Inside and motives of offenders, and investigative and prosecutorial challenges. Victim vulnerabilities .................................... 3 Although police and CMC investigators are the paper’s primary audience, it will Homicide offences ........................................ 3 also be a useful reference for professionals such as clinicians, ambulance officers Investigative challenges ................................ 8 or aged care professionals who may encounter older people at risk of becoming Prosecutorial challenges ............................. 10 homicide victims. Crime prevention opportunities .................. 14 This is the second paper produced by the CMC in a series on “vulnerable” victims. Conclusion .................................................. 15 The first paper, Vulnerable victims: child homicide by parents, examined child References .................................................. 15 homicides committed by a biological or non-biological parent (CMC 2013). Abbreviations ............................................. 17 Appendix A: Extracts from the Criminal Code (Qld) ................................................. -

Barbara Allen

120 Charles Seeger Versions and Variants of the Tunes of "Barbara Allen" As sung in traditional singing styles in the United States and recorded by field collectors who have deposited their discs and tapes in the Archive of American Folk Song in the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. AFS L 54 Edited by Charles Seeger PROBABLY IT IS safe to say that most English-speaking people in the United States know at least one ballad-tune or a derivative of one. If it is not "The Two Sisters, " it will surely be "When Johnny Comes Marching Home"; or if not "The Derby Ram, " then the old Broadway hit "Oh Didn't He Ramble." If. the title is given or the song sung to them, they will say "Oh yes, I know tllat tune." And probably that tune, more or less as they know it, is to them, the tune of the song. If they hear it sung differently, as may be the case, they are as likely to protest as to ignore or even not notice the difference. Afterward, in their recognition or singing of it, they are as likely to incor porate some of the differences as not to do so. If they do, they are as likely to be aware as to be entirely unconscious of having done ·so. But if they ad mit the difference yet grant that both singings are of "that" tune, they have taken the first step toward the study of the ballad-tune. They have acknow ledged that there are enough resemblances between the two to allow both to be called by the same name. -

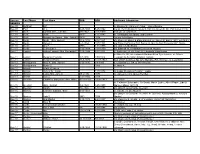

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P. m. Eleanor R. Clark 5-21-1866; stone illegible Bee-09 Purl J. C. 8-25-1898 5-25-1902 s/o Dr. Henry Bosworth & Laura Purl; b/o Aileen B. (Dr. Purl buried in CA) Bee-10 Buck Cynthia (Mrs. John #2) 2-6-1842 11-6-1930 2nd wife of John Buck Bee-10 Buck John 1807 3-25-1887 m.1st-Magdalena Spring; 2nd-Cynthia Bee-10 Buck Magdalena Spring (Mrs. John #1) 1805 1874 1st w/o John Buck Bee-10 Burris Ida B. (Mrs. James) 11-6-1858 2/12/1927 d/o Moses D. Burch & Efamia Beach; m. James R. Burris 1881; m/o Ora F. Bee-10 Burris James I. 5-7-1854 11/8/1921 s/o Robert & Pauline Rich Burris; m. Ida; f/o Son-Professor O.F. Burris Bee-10 Burris Ora F. 1886 2-11-1975 s/o James & Ida Burris Bee-10 Burris Zelma Ethel 7-15-1894 1-18-1959 d/o Elkanah W. & Mahala Ellen Smith Howard Bee-11 Lamkin Althea Leonard (Mrs. Benjamin F.) 7-15-1844 3/17/1931 b. Anderson, IN; d/o Samuel & Amanda Eads Brown b. Ohio Co, IN ; s/o Judson & Barbara Ellen Dyer Lamkin; m. Althea Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Franklin 1-7-1836 1/30/1914 Leonard; f/o Benjamin Franklin Lamkin Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Frank 11-9-1875 12-17-1943 Son of B.F. & Althea; Sp. Am. War Mo., Pvt. -

Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave

Student ID: XXXXXX ENGL3372: Dissertation Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave Table of Contents Introduction 2 Chapter One – ‘I went on down the road’: Cave and the holy blues 4 Chapter Two – ‘I got the abattoir blues’: Cave and the contemporary 15 Chapter Three – ‘Can you feel my heart beat?’: Cave and redemptive feeling 25 Conclusion 38 Bibliography 39 Appendix 44 Student ID: ENGL3372: Dissertation 12 May 2014 Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the lyrics of Nick Cave Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown INTRODUCTION And I only am escaped to tell thee. So runs the epigraph, taken from the Biblical book of Job, to the Australian songwriter Nick Cave’s collected lyrics.1 Using such a quotation invites anyone who listens to Cave’s songs to see them as instructive addresses, a feeling compounded by an on-record intensity matched by few in the history of popular music. From his earliest work in the late 1970s with his bands The Boys Next Door and The Birthday Party up to his most recent releases with long- time collaborators The Bad Seeds, it appears that he is intent on spreading some sort of message. This essay charts how Cave’s songs, which as Robert Eaglestone notes take religion as ‘a primary discourse that structures and shapes others’,2 consistently use the blues as a platform from which to deliver his dispatches. The first chapter draws particularly on recent writing by Andrew Warnes and Adam Gussow to elucidate why Cave’s earlier songs have the blues and his Christian faith dovetailing so frequently. -

English 577.02 Folklore 2: the Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246)

English 577.02 Folklore 2: The Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246) Instructor: Richard F. Green ([email protected]; phone: 292-6065) Office Hours: Wednesday 11:30 - 2:30 (Denney 529) Text: English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ed. F.J. Child, 5 vols (Cambridge, Mass.: 1882- 1898); available online at http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/the-305-child-ballads.aspx.\ August Thurs 22 Introduction: “What is a Ballad?” Sources Tues 27 Introduction: Ballad Terminology: “The Gypsy Laddie” (Child 200) Thurs 29 “From Sir Eglamour of Artois to Old Bangum” (Child 18) September Tues 3 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 1 Thurs 5 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 2 Tues 10 Tragic Ballads Thurs 12 Twa Sisters (Child 10) Tues 17 Lord Thomas and Fair Annet (Child 73) Thurs 19 Romantic Ballads Tues 24 Young Bateman (Child 53) October Tues 1 Fair Annie (Child 62) Thurs 3 Supernatural Ballads Tues 8 Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight (Child 4) Thurs 10 Wife of Usher’s Well (Child 79) Tues 15 Religious Ballads Thurs 17 Cherry Tree Carol (Child 54) Tues 22 Bitter Withy Thurs 24 Historical & Border Ballads Tues 29 Sir Patrick Spens (Child 58) Thurs 31 Mary Hamilton (Child 173) November Tues 5 Outlaw & Pirate Ballads Thurs 7 Geordie (Child 209) Tues 12 Henry Martin (Child 250) Thurs 14 Humorous Ballads Tues 19 Our Goodman (Child 274) Thurs 21 The Farmer’s Curst Wife (Child 278) S6, S7, S8, S9, S23, S24) Tues 24 American Ballads Thurs 26 Stagolee, Jesse James, John Hardy Tues 28 Thanksgiving (PAPERS DUE) Jones, Omie Wise, Pretty Polly, &c. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 310 957 SO 020 170 TITLE Folk Recordings

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 310 957 SO 020 170 TITLE Folk Recordings Selected from the Archive of Folk Culture. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Div. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 59p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indians; Audiodisks; Audiotape Cassettes; *Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Music; *Songs IDENTIFIERS Bahamas; Black Folk Music; Brazil; *Folk Music; *Folktales; Mexico; Morocco; Puerto Rico; Venezuela ABSTRACT This catalog of sound recordings covers the broad range of folk music and folk tales in the United States, Central and South America, the Caribbean, and Morocco. Among the recordings in the catalog are recordings of Afro-Bahain religious songs from Brazil, songs and ballads of the anthracite miners (Pennsylvania), Anglo-American ballads, songs of the Sioux, songs of labor and livelihood, and animal tales told in the Gullah dialect (Georgia). A total of 83 items are offered for sale and information on current sound formats and availability is included. (PPB) Reproductions supplied by EMS are the best that can be made from the original document. SELECTED FROM THE ARCHIVE OF FOLK CULTURE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON. D.C. 20540 U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER IERICI hisdocument has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it C Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction duality Pointsof view or opinions stated in thisdccu- ment do not necessarily represent officral OERI motion or policy AM.