Homeless in America: Examining the Crisis and Solutions to End Homelessness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homelessness and Its Criminalization

Downward Spiral:. Homelessness and Its Criminalization Maria Foscarinis t A city council recently developed a policy that homeless residents "are no longer welcome in the City."' City memoranda describe a plan "continually [to] remov[e] [homeless people] from the places that they are frequenting in the City.". In one phase of what a court later described as the city's "war on the homeless,"' police conducted a "harassment sweep" in which homeless people "were handcuffed, transported to an athletic field for booking, chained to benches, marked with numbers, and held for as long as six hours before being released to another location, some for such crimes as dropping a match, a leaf, or a piece of paper or jaywalking." 3 Over the past decade, as homelessness has increased across the country,4 the number of people living in public places has also grown.5 Emergency shelters, the primary source of assistance, do not provide sufficient space to meet the need even for temporary overnight accommodations; on any given night there are at least as many people living in public as there are sheltered.6 t Executive Director, National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty; A.B. 1977 Barnard College; M.A. 1978, J.D. 1981, Columbia University. I am grateful to Susan Bennett, Stan Herr, and Rick Herz for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article; to Teresa Hinze for her unstinting assistance, and to Bob Ellickson and Peter Margulies for their encouragement. I am grateful to Greg Christianson, Chrysanthe Gussis, Rick Herz, Steve Berman, and Tamar Hagler for their excellent research documenting the trends discussed in the Article. -

Homelessness and Human Rights: Towards an Integrated Strategy

Saint Louis University Public Law Review Volume 19 Number 2 Representing the Poor and Homeless: Innovations in Advocacy (Volume Article 8 XIX, No. 2) 2000 Homelessness and Human Rights: Towards an Integrated Strategy Maria Foscarinis National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/plr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Foscarinis, Maria (2000) "Homelessness and Human Rights: Towards an Integrated Strategy," Saint Louis University Public Law Review: Vol. 19 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/plr/vol19/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Public Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW HOMELESSNESS AND HUMAN RIGHTS: TOWARDS AN INTEGRATED STRATEGY MARIA FOSCARINIS* Years ago, a volunteer team of lawyers staffed a legal clinic at a shelter in Washington, D.C. Any resident who felt a need for legal counsel could come to the folding table we had set up in the shelter hall way. Quite a few did, bringing a wide range of problems: evictions, benefit denials, unpaid wages. While their circumstances were unusually desperate, these clients presented routine legal problems. Others had more complicated stories involving the CIA, radio waves and thought control. These problems we did not generally think of as legal: we referred these clients to the social workers thinking, almost certainly mistakenly, that there was a mental health treatment program for them. -

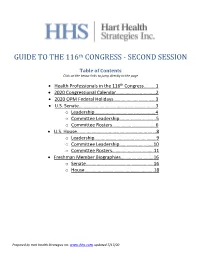

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

Bipartisan Letter Urges Additional Relief Fund Flexibilities and Extended Deadlines IDPH Releases New and Updated Vaccine Inform

5/13/2021 link.ihaonline.org/m/1/42467087/02-b21132-b3e58f5eb0f84ce191345e09344306d8/1/416/521ad1d7-acdc-4b7f-806e-7563bd062853 Click here if you are having trouble viewing this message. Wednesday, May 12, 2021 Bipartisan letter urges additional relief fund flexibilities and extended deadlines The Iowa Hospital Association continues to advocate for an extension to the deadline for hospitals to spend unused funds from the Provider Relief Fund. This week, Reps. Cindy Axne and Mariannette Miller-Meeks led a bipartisan group of 77 members in a letter to the Department of Health and Human Services calling for greater flexibility and additional time for health care providers to use financial assistance they have received from the Provider Relief Fund. Reps. Ashley Hinson and Randy Feenstra also signed the letter, and Sens. Joni Ernst and Chuck Grassley also are advocating for the same changes. Providers face a deadline of Wednesday, June 30, to spend unused funds and have limited options for how funds may be used. The letter notes that some providers have only tapped this assistance as a last resort for fear of being required to return a significant portion. This has resulted in hospitals postponing projects that would greatly help in responding to the pandemic, like converting patient care rooms to negative-pressure rooms. IDPH releases new and updated vaccine information IDPH has released the following new and updated COVID-19 vaccine information: COVID-19 Vaccine Information Brief. Vaccine Access and Wastage Guidance. Vaccine Equity Funding Questions and Answers. These documents are posted to the HAN *3 COVID-19 Vaccine folder. -

Congressional Advocacy and Key Housing Committees

Congressional Advocacy and Key Housing Committees By Kimberly Johnson, Policy Analyst, • The Senate Committee on Appropriations . NLIHC • The Senate Committee on Finance . obbying Congress is a direct way to advocate See below for details on these key committees for the issues and programs important to as of December 1, 2019 . For all committees, you . Members of Congress are accountable to members are listed in order of seniority and Ltheir constituents and as a constituent, you have members who sit on key housing subcommittees the right to lobby the members who represent are marked with an asterisk (*) . you . As a housing advocate, you should exercise that right . HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL CONTACT YOUR MEMBER OF SERVICES CONGRESS Visit the committee’s website at To obtain the contact information for your http://financialservices.house.gov. member of Congress, call the U S. Capitol The House Committee on Financial Services Switchboard at 202-224-3121 . oversees all components of the nation’s housing MEETING WITH YOUR MEMBER OF and financial services sectors, including banking, CONGRESS insurance, real estate, public and assisted housing, and securities . The committee reviews Scheduling a meeting, determining your main laws and programs related to HUD, the Federal “ask” or “asks,” developing an agenda, creating Reserve Bank, the Federal Deposit Insurance appropriate materials to take with you, ensuring Corporation, government sponsored enterprises your meeting does not veer off topic, and including Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and following-up afterward are all crucial to holding international development and finance agencies effective meetings with Members of Congress . such as the World Bank and the International For more tips on how to lobby effectively, refer to Monetary Fund . -

April 28, 2021 the Honorable Rosa Delauro Chair Appropriations

April 28, 2021 The Honorable Rosa DeLauro The Honorable Tom Cole Chair Ranking Member Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Health and Human Services, and Education 2358-B Rayburn House Office Building 2358-B Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Chairwoman DeLauro and Ranking Member Cole: As you begin work on the Fiscal Year 2022 Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations bill, we respectfully request that you provide increased funding at $15.4 million to study the intersection of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome (PACS) at the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Programs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and to include the attached report language to complement this work. While the cause of ME/CFS is unknown, multiple studies have found it has a viral trigger, often following acute infections from the Spanish flu of 1918 to Epstein-Barr to Ebola. Some patients experiencing PACS – so called long haulers – meet the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS and may become permanently disabled.1 Dr. Anthony Fauci during a July 2020 news conference stated that many COVID-19 patients develop symptoms strikingly similar to ME/CFS and that “this is something we really need to seriously look at because it very well might be there is a post-viral syndrome associated with COVID-19.”2 The Institute of Medicine estimated in a 2015 report that between 836,000 and 2.5 million people in the United States suffer from ME/CFS.3 The direct and indirect costs on individuals, the U.S. -

DMDC 2021 Sept

DMDC 2021 Sept. 22 – 24, 2021 Updated July 26, 2021 *Itinerary is subject to change THANK YOU TO PRESENTING SPONSORS Wednesday, Sept. 22 5:30 a.m. (CST) Check-In Begins at Des Moines International Airport Southwest Airlines ticket counter located near baggage claim. Private Breakfast Reception sponsored by Des Moines Airport Authority 6:30 a.m. (CST) Begin Boarding 7 a.m. (CST) Flight departs from Des Moines International Airport Passengers must be checked in at gate by 6:30 a.m. (CST). 10:10 a.m. (EST) Arrive at Washington Dulles International Airport Charter buses to Hilton Hotel on Capitol Hill. 525 New Jersey Ave. N.W., Washington, D.C. 20001 Luggage Holding – Bags will be unloaded by Hotel Bell StaFF and stored at the Hilton Hotel on Capitol Hill until attendees check in and retrieve them after 4:30 p.m. 12 – 2 p.m. DMDC 2021 Delegation Welcome Luncheon and Opening Charge from Jay Byers, President and CEO, Greater Des Moines Partnership and Fred Buie, 2021 Partnership Board Chair Hilton Hotel on Capitol Hill Grand Ballroom Sponsored by Nyemaster Goode, P.C. and The Weitz Company 2 – 2:30 p.m. Break 2:30 – 4:30 p.m. U.S. Chamber Briefing Hilton Hotel on Capitol Hill Ballroom 6 – 8 p.m. Iowa Congressional Reception Hall of States – The Rooftop at 400 N Capitol 444 North Capitol Street N.W., Washington, D.C. 2001 Thursday, Sept. 23 8 – 9:45 a.m. Continental Breakfast and Briefing featuring Iowa’s Congressional Delegation Sponsored by Delta Dental oF Iowa and Principal Financial Group Invited to speak are Iowa’s Congressional Delegation — Senator Chuck Grassley, Senator Joni Ernst, Congresswoman Ashley Hinson, Congresswoman Mariannette Miller-Meeks, Congresswoman Cindy Axne and Congressman Randy Feenstra. -

Public Interest/Public Service Fellows Program Advisory Board (2020-2021)

Public Interest/Public Service Fellows Program Advisory Board (2020-2021) ESHA BHANDARI ’10 Senior Staff Attorney, ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project Esha Bhandari is a senior staff attorney with the ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, where she works on litigation and advocacy to protect freedom of expression and privacy rights in the digital age. She also focuses on the impact of big data and artificial intelligence on civil liberties. She has litigated cases including Sandvig v. Barr, a First Amendment challenge to the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act on behalf of researchers who test for housing and employment discrimination online, and Alasaad v. Wolf, a challenge to suspicionless electronic device searches at the U.S. border. Esha was previously an Equal Justice Works fellow with the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project, where she litigated cases concerning a right to counsel in immigration proceedings and immigration detainer policies. She has argued before multiple federal district and appellate courts about constitutional issues affecting civil rights and liberties. Esha is a graduate of McGill University, where she was a Loran Scholar and received the Allen Oliver Gold Medal in Political Science. She has an M.S. from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and a J.D. from Columbia Law School, where she received the Robert Noxon Toppan Prize in Constitutional Law and the Archie O. Dawson Prize for Advocacy. Esha was a member of the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, the Columbia Law Review, and the Columbia Journal of Gender and Law. Following law school, Esha served as a law clerk to the Hon. -

MBCACA House Cosponsors 117Th Congress 106 As of 6/24/2021 Arizona Raul Grijalva (D-03) Arkansas Rick Crawford (R-01) Bruce

MBCACA House Cosponsors 117th Congress Florida 106 as of 6/24/2021 Gus Bilirakis (R-12) (Original Cosponsor) Kathy Castor (D-14)* (Lead) Arizona Brian Mast (R-18) (Original Cosponsor) Raul Grijalva (D-03) Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-23) (Original Cosponsor) Arkansas Rick Crawford (R-01) Georgia Bruce Westerman (R-04) (Original Cosponsor) Lucy McBath (D-06) American Samoa Illinois Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen (R-At Large) Rodney Davis (R-13) (Original Cosponsor) California Iowa Doug LaMalfa (R-01) (Original Cosponsor) Mariannette Miller-Meeks (IA-02) John Garamendi (D-03) Cindy Axne (D-03) (Original Cosponsor) Doris Matsui (D-06) Randy Feenstra (R-04) Josh Harder (D-10) Mark DeSaulnier (D-11) Kentucky Jackie Speier (D-14) John Yarmuth (D-03) Eric Swalwell (D-15) Salud. Carbajal (D-24) Maine Judy Chu (D-27) Chellie Pingree (D-01) (Original Cosponsor) Adam Schiff (D-28) (Original Cosponsor) Tony Cardenas (D-29) Maryland Brad Sherman (D-30) C.A. Dutch Ruppersberger (D-02) Pete Aguilar (D-31) David Trone (D-06) Grace Napolitano (D-32) Ted Lieu (D-33) Massachusetts Karen Bass (D-37) James McGovern (D-02) Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-40) Lori Trahan (D-03) Ken Calvert (R-42) Jake Auchincloss (D-04) Nanette Diaz Barragan (D-44) (Original Seth Moulton (D-06) (Original Cosponsor) Cosponsor) Ayanna Pressley (D-07) Katie Porter (D-45) (Original Cosponsor) Stephen Lynch (D-08) Alan Lowenthal (D-47) William R. Keating (D-09) (Original Cosponsor) Juan Vargas (D-51) Sara Jacobs (D-53) Michigan Dan Kildee (D-05) Connecticut Andy Levin (MI-09) Joe Courtney (D-02) (Original Cosponsor) Debbie Dingell (D-12) (Original Cosponsor) Jim Himes (D-04) (Original Cosponsor) Jahana Hayes (D-05) Minnesota Angie Craig (D-02) Betty McCollum (D-04) Mary Gay Scanlon (D-05) Tom Emmer (R-06) (Original Cosponsor) Chrissy Houlahan (D-06) Pete Stauber (R-08) (Original Cosponsor) Matt Cartwright (D-08) Dan Meuser (R-09) New Hampshire Guy Reschenthaler (R-14) Chris Pappas (D-01) Glenn Thompson (R-15) Ann M. -

Key Committees for the 116Th Congress

TH KEY COMMITTEES FOR THE 116 CONGRESS APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEES The Senate and House Appropriations Committees determine how federal funding for discretionary programs, such as the Older Americans Act (OAA) Nutrition Program, is allocated each fiscal year. The Subcommittees overseeing funding for OAA programs in both the Senate and the House are called the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies Subcommittees. Listed below, by rank, are the Members of Congress who sit on these Committees and Subcommittees. Senate Labor, Health & Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Subcommittee Republicans (10) Democrats (9) Member State Member State Roy Blunt, Chairman Missouri Patty Murray, Ranking Member Washington Richard Shelby Alabama Dick Durbin Illinois Lamar Alexander Tennessee Jack Reed Rhode Island Lindsey Graham South Carolina Jeanne Shaheen New Hampshire Jerry Moran Kansas Jeff Merkley Oregon Shelley Moore Capito West Virginia Brian Schatz Hawaii John Kennedy Louisiana Tammy Baldwin Wisconsin Cindy Hyde-Smith Mississippi Chris Murphy Connecticut Marco Rubio Florida Joe Manchin West Virginia James Lankford Oklahoma Senate Appropriations Committee Republicans (16) Democrats (15) Member State Member State Richard Shelby, Chairman Alabama Patrick Leahy, Ranking Member Vermont Mitch McConnell Kentucky Patty Murray Washington Lamar Alexander Tennessee Dianne Feinstein California Susan Collins Maine Dick Durbin Illinois Lisa Murkowski Alaska Jack Reed Rhode Island Lindsey Graham South Carolina -

Monmouth University Poll IOWA: DEMS LEAD in 3 of 4 HOUSE

Please attribute this information to: Monmouth University Poll West Long Branch, NJ 07764 www.monmouth.edu/polling Follow on Twitter: @MonmouthPoll _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Released: Contact: Thursday, October 22, 2020 PATRICK MURRAY 732-979-6769 (cell); 732-263-5858 (office) [email protected] Follow on Twitter: @PollsterPatrick IOWA: DEMS LEAD IN 3 OF 4 HOUSE RACES Open seats: Dem pulls ahead in IA2; GOP lead narrows in IA4 West Long Branch, NJ – The U.S. House race in Iowa’s 2nd Congressional District has shifted to the Democrat’s favor while the Republican’s edge in the 4th has decreased since the summer, according to the Monmouth (“Mon-muth”) University Poll. Two first-term Democratic U.S. House incumbents in Iowa remain in strong position to be reelected in the 1st and the 3rd. “Democrats appear to be on track to retain the three House seats they currently hold and are making a run in a deep red district,” said Patrick Murray, director of the independent Monmouth University Polling Institute. IOWA CD1: First-term Rep. Abby Finkenauer holds a sizable lead over state legislator Ashley Hinson in her bid to win a second term. The race stands at 52% for the Democrat to 44% for the Republican among all registered voters, with 3% undecided. The incumbent maintains her advantage among likely voters in a high turnout scenario (54% to 44%). Finkenauer’s high turnout 10-point lead is similar to the 11-point lead she held in Monmouth’s August poll. Finkenauer has a 15-point registered voter edge (55% to 40%) in the four counties she won by just over 13 points combined in 2018 (including Black Hawk, Dubuque, Linn, Winneshiek). -

United States Congress Washington DC, 20510

United States Congress Washington DC, 20510 June 1, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker of the House Minority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: We, a bipartisan group of representatives, remain committed to fighting the pandemic and the economic downturn to help the American people through this hardship. The unemployment rate is nearly 15%, and GDP could fall as much as 30%. We must confront the economic fallout from this crisis head on. As the crisis recedes and our nation recovers, we cannot ignore the pressing issue of the national debt, which could do irreparable damage to our country. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the debt held by the public is likely to exceed 100 percent of GDP in just a few months, and it will hit record levels in a few years. In addition, trust funds for some of our most critical programs will face exhaustion far sooner than we expected as a result of the current crisis. Trust fund insolvency threatens serious hardship for those who depend on the programs. We, therefore, respectfully request that further pandemic-response legislation include provisions for future budget reforms to ensure we confront these issues when the economy is strong enough. These reforms should have broad, bipartisan support. They should not stand in the way of our making the necessary decisions to deal with the crisis at hand. They should ensure that, in addition to addressing health and economic needs, we lay the foundation for a sustainable fiscal future by building on reforms with established bipartisan support.