The Burning Question: Claims and Counter Claims on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Heritage Values and to Identify New Values

FLORISTIC VALUES OF THE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS WORLD HERITAGE AREA J. Balmer, J. Whinam, J. Kelman, J.B. Kirkpatrick & E. Lazarus Nature Conservation Branch Report October 2004 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment (World Heritage Area Vegetation Program). Commonwealth Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment or those of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. ISSN 1441–0680 Copyright 2003 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment. Published by Nature Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph: Alpine bolster heath (1050 metres) at Mt Anne. Stunted Nothofagus cunninghamii is shrouded in mist with Richea pandanifolia scattered throughout and Astelia alpina in the foreground. Photograph taken by Grant Dixon Back Cover Photograph: Nothofagus gunnii leaf with fossil imprint in deposits dating from 35-40 million years ago: Photograph taken by Greg Jordan Cite as: Balmer J., Whinam J., Kelman J., Kirkpatrick J.B. & Lazarus E. (2004) A review of the floristic values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2004/3. Department of Primary Industries Water and Environment, Tasmania, Australia T ABLE OF C ONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................................1 1. -

Characteristics of Interstate and Overseas Bushwalkers in the Arthur Ranges, South West Tasmania

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERSTATE AND OVERSEAS BUSHWALKERS IN THE ARTHUR RANGES, SOUTH-WEST TASMANIA By Douglas A. Grubert & Lorne K. Kriwoken RESEARCH REPORT RESEARCH REPORT SERIES The primary aim of CRC Tourism's research report series is technology transfer. The reports are targeted toward both industry and government users and tourism researchers. The content of this technical report series primarily focuses on applications, but may also advance research methodology and tourism theory. The report series titles relate to CRC Tourism's research program areas. All research reports are peer reviewed by at least two external reviewers. For further information on the report series, access the CRC website [www.crctourism.com.au]. EDITORS Prof Chris Cooper University of Queensland Editor-in-Chief Prof Terry De Lacy CRC for Sustainable Tourism Chief Executive Prof Leo Jago CRC for Sustainable Tourism Director of Research National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Grubert, Douglas. Characteristics of interstate and overseas bushwalkers in the Arthur Ranges, South West Tasmania. Bibliography. ISBN 1 876685 83 2. 1. Hiking - Research - Tasmania - Arthur Range. 2. Hiking - Tasmania - Arthur Range - Statistics. 3. National parks and reserves - Public use - Tasmania - Arthur Range. I. Kriwoken, Lorne K. (Lorne Keith). II. Cooperative Research Centre for Sustainable Tourism. III. Title. 796.52209946 © 2002 Copyright CRC for Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd All rights reserved. No parts of this report may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by means of electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Any enquiries should be directed to Brad Cox, Director of Communications or Trish O’Connor, Publications Manager to [email protected]. -

Managing Seismic Risk for Hydro Tasmania's Dams

MANAGING SEISMIC RISK FOR HYDRO TASMANIA'S DAMS ANDREW PATILE HYDRO TASMANIA INVITED SPEAKER Andrew Pattie has held the position of Dam Safety Manager with Hydro Tasmania for the last 4 years and is responsible for managing the safety of 54 dams. Prior to his current position, Andrew had 10 years experience as a civil engineer in the hydro-electric power industry in New Zealand. Dam owners devote considerable resources to managing seismic risks in New Zealand's dynamic landscape, and Andrew has been involved in a large number of earthquake engineering projects, ranging from seismotectonic studies to post-earthquake inspections of damaged facilities. (Full paper not available at time ofprinting) Experience from a number of large earthquakes worldwide has shown that dams have a very good seismic resistance, and have caused essentially nil loss of life during the last two decades. In the same period, there have been several hundred thousand fatalities due to earthquake effects such as building collapses, tsunamis, landslides and post-earthquake fires. The excellent seismic performance record of dams, together with the low level of seismic activity in Tasmania, indicates that Hydro Tasmania's dams pose an infinitesimal risk to the population of Tasmania. However, seismic risks cannot be completely ignored and responsible dam ownership requires that they still need to be considered as part of risk management activities. This paper describes Hydro Tasmania's approach to managing seismic risk for their 54 dams. The primary activities are: • determining regional and site specific seismic hazard • re-assessing the seismic resistance of dams, using analysis techniques and knowledge of precedent behaviour of dams during earthquakes • ensuring emergency preparedness includes post-earthquake response procedures. -

A Review of Geoconservation Values

Geoconservation Values of the TWWHA and Adjacent Areas 3.0 GEOCONSERVATION AND GEOHERITAGE VALUES OF THE TWWHA AND ADJACENT AREAS 3.1 Introduction This section provides an assessment of the geoconservation (geoheritage) values of the TWWHA, with particular emphasis on the identification of geoconservation values of World Heritage significance. This assessment is based on: • a review (Section 2.3.2) of the geoconservation values cited in the 1989 TWWHA nomination (DASETT 1989); • a review of relevant new scientific data that has become available since 1989 (Section 2.4); and: • the use of contemporary procedures for rigorous justification of geoconservation significance (see Section 2.2) in terms of the updated World Heritage Criteria (UNESCO 1999; see this report Section 2.3.3). In general, this review indicates that the major geoconservation World Heritage values of the TWWHA identified in 1989 are robust and remain valid. However, only a handful of individual sites or features in the TWWHA are considered to have World Heritage value in their own right, as physical features considered in isolation (eg, Exit Cave). In general it is the diversity, extent and inter-relationships between numerous features, sites, areas or processes that gives World Heritage significance to certain geoheritage “themes” in the TWWHA (eg, the "Ongoing Natural Geomorphic and Soil Process Systems" and “Late Cainozoic "Ice Ages" and Climate Change Record” themes). This "wholistic" principle under-pinned the 1989 TWWHA nomination (DASETT 1989, p. 27; see this report Section 2.3.2), and is strongly supported by the present review (see discussion and justification of this principle in Section 2.2). -

Wellington Park Historic Tracks and Huts Network Comparative Analysis

THE HISTORIC TRACK & HUT NETWORK OF THE HOBART FACE OF MOUNT WELLINGTON Interim Report Comparative Analysis & Significance Assessment Anne McConnell MAY 2012 For the Wellington Park Management Trust, Hobart. Anne D. McConnell Consultant - Cultural Heritage Management, Archaeology & Quaternary Geoscience; GPO Box 234, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001. Background to Report This report presents the comparative analysis and significance assessment findings for the historic track and hut network on the Hobart-face of Mount Wellington as part of the Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project. This report is provided as the deliverable for the second milestone for the project. The Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project is a project of the Wellington Park Management Trust. The project is funded by a grant from the Tasmanian government Urban Renewal and Heritage Fund (URHF). The project is being undertaken on a consultancy basis by the author, Anne McConnell. The data contained in this assessment will be integrated into the final project report in approximately the same format as presented here. Image above: Holiday Rambles in Tasmania – Ascending Mt Wellington, 1885. [Source – State Library of Victoria] Cover Image: Mount Wellington Map, 1937, VW Hodgman [Source – State Library of Tasmania] i CONTENTS page no 1 BACKGROUND - THE EVOLUTION OF 1 THE TRACK & HUT NETWORK 1.1 The Evolution of the Track Network 1 2.2 The Evolution of the Huts 18 2 A CONTEXT FOR THE TRACK & HUT 29 NETWORK – A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 2.1 -

The Lake Pedder Decision

Hrasky, S. , & Jones, M. J. (2016). Lake Pedder: Accounting, environmental decision-making, nature and impression management. Accounting Forum, 40(4), 285-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2016.06.005 Peer reviewed version License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1016/j.accfor.2016.06.005 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the accepted author manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Elsevier at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2016.06.005. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Lake Pedder: Accounting, Environmental Decision-Making, nature and impression management Sue Hrasky and Michael Jones University of Tasmania, University of Bristol Acknowledgements We wish to thank participants at the 15th Financial Reporting and Business Communication Conference, Bristol, July 2011, the 23rd International Congress on Social and Environmental Accounting Research (CSEAR), St Andrews, September 2011 and the 10th CSEAR Australasian Conference, Launceston, December 2011, for their helpful comments and suggestions. My thanks also to Claire Horner for her help collecting data. Finally, I would like to thank Glen Lehman and an anonymous reviewer Corresponding Author Department of Accounting and Finance University of Bristol 8 Woodland Road, Bristol BS8 1TN, UK Email: [email protected] Phone: +44 (0)117 33 18286 Lake Pedder: Accounting, Environmental Decision-Making, Nature and Impression Management Abstract This paper looks at the role of accounting in a major environmental infrastructural project the flooding of Lake Pedder in Tasmania in the 1960s. -

AEES Newsletter

The Editor: Kevin McCue AEES is a Technical Society of AGSO Canberra ACT 2601 IEAust The Institution of Engineers [email protected] Australia and is affiliated with IAEE fax: 61 (0)2 6249 9969 Secretariat: Barbara Butler [email protected] 2/2000 AEES Newsletter Contents and committee members were considered and decisions President’s Perambulations ......................... 1 taken on the content of the next draft. AEES 2000 Conference & AGM ……………. 1 Elsewhere in this newsletter you are invited to The Society Website/email list .................... 2 apply for a research scholarship or register for post- Nuggets from the Newsgroup .............…….. 2 earthquake activities. These invitations derive from Earthquakes in Australia, 1999 …….……….. 3 our AGM in Sydney last year. Recent strong motion recordings ………….… 3 Letter to Editor ..................…………..……. 5 Bill Boyce Obituary –Dr Malcolm Somerville ………….. 5 Forthcoming Conferences.....................….... 7 Report: 12th WCEE ………………………….. 7 AEES 2000 Conference and AGM New Books and old …………………………… 7 Earthquake Engineering Research Scholarship .. 8 The conference theme: Dams, Fault Scarps and Earthquakes. The theme is broad enough to be of interest to PRESIDENT’S PERAMBULATIONS engineers, geologists, seismologists, emergency managers and planners. Along with about 2,000 other delegates, including 30 or so from Australia, I attended the 12th World Venue: Conference on Earthquake Engineering in Auckland The main lecture theatre at the Geology from 30 January – 4 February, 2000. The conference Department, University of Tasmania in Hobart. was very well organised and the offerings ranged over key-note speakers giving state-of-the-art addresses on Date: topics of interest, theme sessions with speakers, Wednesday 15 to Friday 17 November 2000 poster sessions, plenary sessions on the Turkey and Taiwan earthquakes, a public debate on our effectiveness in reducing earthquake risk and several Conference dinner: social events. -

Track, Macquarie Harbour to Upper Huon

(No. 106.) 188 I. TA S M A NI A·. LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL. TRACK, MACQUARIE HARBOUR TO UPPER HOON: REPOR'I'S OF MESSRS. JONES AND COUNSEL, WITH INSTRUCTIONS. Laid npon the; Table by Mr. Moore, and ordered by the Council to be printed, · · - October 27, 1881. INSTRUCTIONS issued to Mr. Surveyor JoNES in reference to the Expedition which started from Macquarie Harbour in July last, and Mr . .JoNEs's Report; also Instruc tions issued to Mr. CouNsEL, who went to the relief of the said Expedition, and Mr. ConNSEL's Report in connection there'UJith. Lands and Works Office, Hobart, 14th June, 1881. MEMORANDUM OF INSTRUCTION. MR. Surveyor Jones will proceed to Macquarie Harbour on the West Coast in the ketch Esk, now ready for sea, taking with him the necessary outfit for a surveying or exploration party. He will examine, the country between Macquarie Harbour and the Craycraft River, in the Valley of the Huon (to which river a track has recently been cleared by the Government), with the view of ascertaining whether a practicable Horse-track ran be found, subsequently capable of being converted into a road, so as to open up communication between Hobart and the West Coast at Macquarie Harbour. The services of Mr. M'Partlan, who has a thorough knowledge of the country, have been arranged for, who will accompany Mr. Jones and render every assistance: A careful examination of the country will be necessary, with the view to the adoption of a track that presents the least engineering difficulties and secures the most ad-rnntageous terminus, either on the River Gordon in the vicinity of Pyramid Island, or on Macquarie Harbour in the vicinity of Birch's Inlet, or any other point on. -

Strategic Plan

Strategic Plan 2018-2021 Outside cover image: Pandani and views from Mount Anne, Southwest National Park. Inside cover image: Grass Point is a family-friendly walk, South Bruny Island National Park. CONTENTS 1 _________ MESSAGE FROM THE PREMIER OF TASMANIA 3 ________ MESSAGE FROM THE DEPUTY SECRETARY 5 ________OUR CONSERVATION FOOTPRINT 6 ________OUR ROLE & RESPONSIBILITIES 7 ________OUR CORPORATE OBJECTIVES 8 ________OUR PRINCIPLES 11 _______INTEGRATED PLANNING 12 _______OUR ASPIRATIONS 15 _______OUR GOALS 17 _______ GOAL 1 – INSPIRING AND ENJOYABLE EXPERIENCES FOR VISITORS 23 ______ GOAL 2 – A HEALTHY, RESILIENT AND UNIQUELY TASMANIAN LANDSCAPE 29 ______ GOAL 3 – PRODUCTIVE AND SUSTAINABLE LAND USE THAT BENEFITS TASMANIA’S ECONOMY 35 ______ GOAL 4 – OUR ESTATE IS RELEVANT TO, AND VALUED BY, OUR COMMUNITIES 43 ______ GOAL 5 – A SUSTAINABLE, CAPABLE AND CONTEMPORARY ORGANISATION Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service acknowledges and pays respect to Tasmanian Aboriginal people as the traditional and original owners, and continuing custodians of this land and acknowledges Elders – past, present and emerging. Image: Star light, Ben Lomond National Park. Message from the PREMIER OF TASMANIA, Minister for Parks National parks are very important to the people of lutruita / Tasmania and to their way of life. They are important places for me and my family. We treasure our time in the outdoors and there is nowhere more beautiful in the world. I recognise the intrinsic values of our parks and reserves. That is why I deliberately chose to lead the Parks portfolio, to elevate the work of the Parks and Wildlife Service and our unique and extraordinary landscapes in the minds of both my Cabinet and the community. -

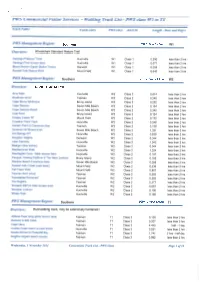

Walking Track List - PWS Class Wl to T4

PWS Commercial Visitor Services - Walking Track List - PWS class Wl to T4 Track Name FieldCentre PWS class AS2156 Length - Kms and Days PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: VV1 Overview: Wheelchair Standard Nature Trail Hastings Platypus Track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.290 less than 2 hrs Hastings Pool access track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.077 less than 2 hrs Mount Nelson Signal Station Tracks Derwent W1 Class 1 0.059 less than 2 hrs Russell Falls Nature Walk Mount Field W1 Class 1 0.649 less than 2 hrs PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: W2 Overview: Standard Nature Trail Arve Falls Huonville W2 Class 2 0.614 less than 2 hrs Blowhole circuit Tasman W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Cape Bruny lighthouse Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.252 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.154 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Beach Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.345 less than 2 hrs Coal Point Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.124 less than 2 hrs Creepy Crawly NT Mount Field W2 Class 2 0.175 less than 2 hrs Crowther Point Track Huonville W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Garden Point to Carnarvon Bay Tasman W2 Class 2 3.138 less than 2 hrs Gordons Hill fitness track Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 1.331 less than 2 hrs Hot Springs NT Huonville W2 Class 2 0.839 less than 2 hrs Kingston Heights Derwent W2 Class 2 0.344 less than 2 hrs Lake Osbome Huonville W2 Class 2 1.042 less than 2 hrs Maingon Bay lookout Tasman W2 Class 2 0.044 less than 2 hrs Needwonnee Walk Huonville W2 Class 2 1.324 less than 2 hrs Newdegate Cave - Main access -

Spreadsheet Listing Contents of All Recorded Issues

TFNC tasnatcontentslist — Index printed 10-07-16, Index page 1/22 Year Month Vol No Page To Title Author1 Author2 Author3 Author4 Author5 Author6 Author7 1907 April 1 1 1 1 Ourselves Anon. 1907 April 1 1 1 5 The Coccidea: a family of remarkable insects Lea, A.M. 1907 April 1 1 5 6 Club notes: January meeting; March meeting Anon. 1907 April 1 1 6 10 Swan shooting on the east coast of Tasmania Elliott, E.A. 1907 April 1 1 10 11 Club notes: list of members Anon. 1907 April 1 1 11 12 The breeding habits of bronzewing pigeons Roberts, M.G. Camp out of the Field Naturalists' Club on Bruni [sic] Island, 1907 September 1 2 1 3 Elliott, E.A. Easter, 1907 1907 September 1 2 3 8 Tasmanian quail and game propagation Reid, A.R. 1907 September 1 2 8 9 A parasite upon flies Nicholls, H.M. Club notes: April meeting; May meeting; August meeting; 1907 September 1 2 10 11 Anon. miscellaneous observations (beetle/bush-rats; ground thrush) An entomologist's cycling trip to Cloncurry (Queensland) (incl. 1907 September 1 2 12 13 Hacker, H. note by Arthur M. Lea) Club notes: excursion to Botanic Gardens; excursion to South 1907 September 1 2 14 14 Anon. Bridgewater; printing fund Notes on the amorpholithes of the Tasmanian aborigines. No. 1.- 1907 September 1 2 14 19 Noetling, F. the native quarry on Coal Hill, near Melton Mowbray Club notes: annual report; statement of receipts and expenditure 1907 September 1 2 19 20 Anon. -

Tasmanian Overland

Tasmanian Overland J GR HARDING (Plates 41-44) As Earth's wild places contract, so have lands once reviled become our new adventure playgrounds. Such has been the experience ofTasmania, which first intruded upon the European conscious ness with Abel Tasman's discovery in 1642 - 128 years before Captain Cook's Australian landfall. Christened by Tasman Van Diemen's Land, its geography remained a mystery until Flinders' circumnavigation in 1799 which established it as an island rather than an appendage of the mainland. Four years later the first settlers arrived and starved. For the next 50 years of the 19th century, Van Diemen's Land became notorious as the principal penal settlement for Britain's transported convicts. In convict lore this was the Fatal Shore, the land of white slavery, and 'to plough Van Diemen's Land' argot for a convict's life of retribution. When transportation was finally abolished in 1853 and the name Tasmania substituted for Van Diemen's Land, the systemized brutality which had characterized the white man's life-style had been transmitted into a campaign of genocide against the Aborigines. Within 45 years of British settlement, the dreamtime had turned nightmare and primitive man had been exterminated from the land he had inhabited for millennia. For many years, little was written or read of Tasmania's 19th-century history; but as time shades and perceptions change, the convict stain has been expunged and to modern visitors the reputation of Victorian Tasmania would be incomprehensible. In the island continent of Australia, the flattest and driest on earth, whose predominant physical characteristic is inconspicuousness, this offshore isle with abundant rainfall, forests and mountains is almost unique in its display of genuinely dramatic scenery.