The Vine and the Son of Man the NT, and It Is Not Used Extensively at Qumran, Which Are Two of the Frequent Stimuli for Such Investigations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalm 80: an Exegetical Discussion on the Model of an Abandoned Child

Scriptura 119 (2020:1), pp. 1-15 http://scriptura.journals.ac.za http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/119-1-1454 PSALM 80: AN EXEGETICAL DISCUSSION ON THE MODEL OF AN ABANDONED CHILD Schalk Treurnicht Department Old and New Testament Stellenbosch University Abstract Psalm 80 uses a wide variety of metaphors to describe the way Israel saw God in their present context. This context is before the fall of Samaria to the Assyrians. It was a time of uncertainty, with many questions on God’s role in Israel’s future and God’s role in their present suffering. They may have asked, are they suffering because God has forgotten or abandoned them? Due to the uncertainty the psalm, which is a communal lament, asks God not to forget them and to return to them. This is done by referring to God’s past relationship with Israel, reminding God of the good parent-child relationship they once had. In Psalm 80 different metaphors work together to create this model of parent and child, with God portrayed not as a good parent, but rather a wicked one. But all is not lost, and Israel knows their lives can be saved by God choosing to return to them and to become, once again, the good parent, who keeps them safe. In this exegetical discussion on Psalm 80, I want to use these metaphors to help develop this model of Israel as an abandoned child and to conclude with the image that this portrays. The metaphor of Israel as child does not appear in Psalm 80, thus, the different metaphors that do appear, each say something about the relational experience Israel had with God. -

Jesus As the Son of Man in Mark Andres A

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-24-2014 Jesus as the Son of Man in Mark Andres A. Tejada-Lalinde [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14040867 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tejada-Lalinde, Andres A., "Jesus as the Son of Man in Mark" (2014). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1175. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1175 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida JESUS AS THE SON OF MAN IN MARK A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Andrés Tejada-Lalinde 2014 To: Dean Kenneth G. Furton College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Andrés Tejada-Lalinde, and entitled Jesus as the Son of Man in Mark, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Ana María Bidegain Christine Gudorf Erik Larson, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 24, 2014. The thesis of Andrés Tejada-Lalinde is approved. Dean Kenneth G. Furton College of Arts and Sciences Dean Lakshmi N. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

A Six Week Study in the Book of PSALMS Window to the Soul: a Six Week Study in the Book of Psalms

W t I o N SSOOUULL D t O h W e A Six Week Study in the book of PSALMS Window to the Soul: A Six Week Study in the Book of Psalms Since the inception of the Church, the psalms have been the sweet hymnbook by which God’s people have praised him for His goodness, kindness and Glory. They contain words of comfort in times of pain and encouragement for those who suffer. They are an example to us of how to be authentic in our struggles and honest in our failures, while always trusting Him to restore our souls. More than communicating a story, the psalms communicate experience, feeling, and emotion. As you study, remember that “The word of God is living and active…it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart” (Hebrews 4:12). God’s Word touches the depths of our souls, and leads us to the one who has all we need. Whether you are in a season of pain or sweet blessing, you can find rest as you read and study… The Psalms. Session 1: Psalm 100 The Elements of a Psalm Session 2: Psalm 100, Jonah 2 Psalms of Praise Session 3: Psalms 22, 80 Psalms of Lament Session 4: Psalm 51 Psalms of Penitence Session 5: Psalms 96, 99 Psalms of Kingship Session 6: Chapters 1, 19 Psalms of Wisdom 2 Session 1: Psalm 100 The Elements of a Psalm Helpful Hints: o The English word “psalms” is a Greek word simply spelled in Roman letters. The Greek word originally meant a striking or twitching of the fingers on a string. -

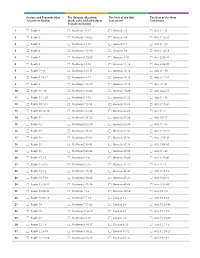

(Old Testament Books) the Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John

Psalms and Proverbs (Old The Gospels: Matthew, The Rest of the Old The Rest of the New Testament Books) Mark, Luke and John (New Testament Testament Testament Books) 1 Psalm 1 Matthew 1:1-17 Genesis 1-2 Acts 1:1-11 2 Psalm 2 Matthew 1:18-25 Genesis 3-4 Acts 1:12-26 3 Psalm 3 Matthew 2:1-12 Genesis 5-6 Acts 2:1-13 4 Psalm 4 Matthew 2:13-18 Genesis 7-8 Acts 2:14-28 5 Psalm 5 Matthew 2:19-23 Genesis 9-10 Acts 2:29-41 6 Psalm 6 Matthew 3:1-12 Genesis 11-12 Acts 2:42-47 7 Psalm 7:1-9 Matthew 3:13-17 Genesis 13-14 Acts 3:1-10 8 Psalm 7:10-17 Matthew 4:1-11 Genesis 15-16 Acts 3:11-26 9 Psalm 8 Matthew 4:12-17 Genesis 17-18 Acts 4:1-21 10 Psalm 9:1-10 Matthew 4:18-25 Genesis 19-20 Acts 4:22-37 11 Psalm 9:11-20 Matthew 5:1-12 Genesis 21-22 Acts 5:1-16 12 Psalm 10:1-11 Matthew 5:13-16 Genesis 23-24 Acts 5:17-42 13 Psalm 10:12-18 Matthew 5:17-20 Genesis 25-26 Acts 6:1-7 14 Psalm 11 Matthew 5:21-26 Genesis 27-28 Acts 6:8-15 15 Psalm 12 Matthew 5:27-30 Genesis 29-30 Acts 7:1-16 16 Psalm 13 Matthew 5:31-32 Genesis 31-32 Acts 7:17-32 17 Psalm 14 Matthew 5:33-37 Genesis 33-34 Acts 7:33-43 18 Psalm 15 Matthew 5:38-42 Genesis 35-36 Acts 7:44-60 19 Psalm 16 Matthew 5:43-48 Genesis 37-38 Acts 8:1-25 20 Psalm 17:1-5 Matthew 6:1-4 Genesis 39-40 Acts 8:26-40 21 Psalm 17:6-15 Matthew 6:5-15 Genesis 41-42 Acts 9:1-9 22 Psalm 18:1-6 Matthew 6:16-18 Genesis 43-44 Acts 9:10-19 23 Psalm 18:7-19 Matthew 6:19-24 Genesis 45-46 Acts 9:20-31 24 Psalm 18:20-29 Matthew 6:25-34 -

The Christological Aspects of Hebrew Ideograms Kristološki Vidiki Hebrejskih Ideogramov

1027 Pregledni znanstveni članek/Article (1.02) Bogoslovni vestnik/Theological Quarterly 79 (2019) 4, 1027—1038 Besedilo prejeto/Received:09/2019; sprejeto/Accepted:10/2019 UDK/UDC: 811.411.16'02 DOI: https://doi.org/10.34291/BV2019/04/Petrovic Predrag Petrović The Christological Aspects of Hebrew Ideograms Kristološki vidiki hebrejskih ideogramov Abstract: The linguistic form of the Hebrew Old Testament retained its ancient ideo- gram values included in the mystical directions and meanings originating from the divine way of addressing people. As such, the Old Hebrew alphabet has remained a true lexical treasure of the God-established mysteries of the ecclesiological way of existence. The ideographic meanings of the Old Hebrew language represent the form of a mystagogy through which God spoke to the Old Testament fathers about the mysteries of the divine creation, maintenance, and future re-creation of the world. Thus, the importance of the ideogram is reflected not only in the recognition of the Christological elements embedded in the very structure of the Old Testament narrative, but also in the ever-present working structure of the existence of the world initiated by the divine economy of salvation. In this way both the Old Testament and the New Testament Israelites testify to the historici- zing character of the divine will by which the world was created and by which God in an ecclesiological way is changing and re-creating the world. Keywords: Old Testament, old Hebrew language, ideograms, mystagogy, Word of God, God (the Father), Holy Spirit, Christology, ecclesiology, Gospel, Revelation Povzetek: Jezikovna oblika hebrejske Stare Zaveze je obdržala svoje starodavne ideogramske vrednote, vključene v mistagoške smeri in pomene, nastale iz božjega načina nagovarjanja ljudi. -

Nathaniel Schmidt Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol

The "Son of Man" in the Book of Daniel Author(s): Nathaniel Schmidt Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 19, No. 1 (1900), pp. 22-28 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259068 Accessed: 12/03/2010 14:28 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sbl. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org 22 JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE. The " Son of Man" in the Book of Daniel. -

Hebreo: Rossi's Mantua House Program

2019-2020: The Fellowship of Early Music Hebreo: ROSSI’S MANTUA Guest Ensemble Profeti della Quinta JANUARY 31 & FEBRUARY 1, 2020 2019-2020 Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St.Paul’s Centre Season Sponsor THANK YOU! This production is made possible by The David Fallis Fund for Culture Bridging Programming It is with sincere appreciation and gratitude that we salute the following supporters of this fund: Anonymous (2) Matthew & Phyllis Airhart Michelle & Robert Knight Rita-Anne Piquet The Pluralism Fund Join us at our Intermission Café! The Toronto Consort is happy to offer a wide range of refreshments: BEVERAGES SNACKS PREMIUM ($2) ($2) BAKED GOODS ($2.50) Coffee Assortment of Chips Assortment by Tea Assortment of Candy Bars Harbord Bakery Coke Breathsavers Diet Coke Halls San Pellegrino Apple Juice Pre-order in the lobby! Back by popular demand, pre-order your refreshments in the lobby and skip the line at intermission! PROGRAM The Songs of Salomon HaShirim asher liShlomo Music by Salomone Rossi and Elam Rotem Salomone Rossi Lamnatséah ‘al hagitít Psalm 8 (c.1570-1630) Elohím hashivénu Psalm 80:4, 8, 20 Elam Rotem Kol dodí hineh-zéh bá Song of Songs 2: 8-13 Siméni chachotám al libécha Song of Songs 8: 6-7 Girolamo Kapsperger Passacaglia (ca. 1580-1651) Salomone Rossi Shir hama’alót, ashréy kol yeré Adonái Psalm 128 Hashkivénu Evening prayer Elam Rotem Shechoráh aní venaváh Song of Songs 1: 5-7 Aní yeshenáh velibí er Song of Songs 5:2-16, 6:1-3 INTERMISSION – Join us for the Intermission Café, located in the gym. -

Paul's Use of Psalms: Quotations, Allusions

Faculty of Theology University of Helsinki PAUL’S USE OF PSALMS QUOTATIONS, ALLUSIONS, AND PSALM CLUSTERS IN ROMANS AND FIRST CORINTHIANS Marika Pulkkinen DOCTORAL DISSERTATION To be presented for public discussion with the permission of the Faculty of Theology of the University of Helsinki, in Athena building, room 107, on the 8th of May, 2020 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2020 ISBN 978-951-51-6040-9 (pbk.) ISBN 978-951-51-6041-6 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2020 Abstract This study examines how Paul uses psalms and how this is related to the uses and status of the psalms in the late Second Temple Judaism. The study focuses on clusters of explicit and subtle references to psalms in Paul’s Letter to the Romans and his First Letter to the Corinthians. Furthermore, the study covers the psalm quotations paired together or with another scriptural text and a selection of four individually occurring quotations from a psalm. The following questions are answered in this study: What was the status of psalms within Jewish scriptures for Paul? What does their use as different clusters tell us of the source of Paul’s citations and exegesis of the psalms? How do the individually occurring quotations from psalms differ from quotation clusters or pairs of quotations? What kind of scriptural texts does Paul combine when quoting from or referring to the psalms, and which interpretive technique enables him to do so? The study is divided into two main parts—Part I: Psalms in the Late Second Temple Period; and Part II: Paul’s Use of Psalms. -

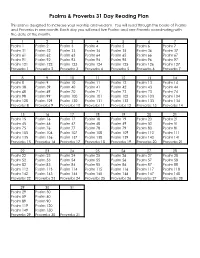

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

Daniel's Vision of the Son Of

Daniel’s Vision of the Son of Man E.J. Young, Th.M., Ph.D. [p.3] One of the most majestically conceived scenes in the entire Old Testament is that of the judgment in which a figure like the Son of man came with the clouds of heaven and was brought before the Ancient of days. The vision has to do with the judgment of four beasts which represent human kings, and also with the establishment of the kingdom of God.1 At its central point is the scene of judgment and the introduction of the Son of man. Concerning this strange figure there has been much discussion, and it will be our purpose to ascertain, in so far as that is possible, his identity. A Survey of Daniel VII The seventh chapter of Daniel relates events which took place in the first year of Belshazzar king of Babylon.2 During this year a dream came to Daniel, the content of which he recorded. In this dream he saw the great sea, a figure of humanity itself.3 From the sea there arose four beasts, each diverse from the others. These beasts did not arise simultaneously, but one after another. The first is said to have been like a lion, with the wings of an eagle. In its flight to heaven it was checked, the heart of a man was given to it and it was made to stand upon its feet as a man. The second beast was compared with a bear raised up on one side. The third resembled a leopard, and the fourth was nondescript, compared to no animal. -

Preaching on Psalms for Advent J

Preaching on Psalms for Advent J. Clinton McCann, Jr. Eden Theological Seminary, Webster Groves, Missouri In talking about the Psalms with pastors and seminary students, I have found that they are frequently surprised to hear me say that the Psalms should be preached. They either assume or have been taught that since the Psalms originated primarily as liturgical materials, they should continue to be used that way — as calls to worship, hymns, and prayers. Even the Psalter reading after the Old Testament lesson is usually called a "gradual," which means a response to provide a transition to the New Testament lessons. What this point of view overlooks is the canonical process which led to the final form of the Book of Psalms. As Brevard Childs puts it: I would argue that the need for taking seriously the canonical form of the Psalter would greatly aid in making use of the psalms in the life of the Christian Church. Such a move would not disregard the historical dimensions of the Psalter, but would attempt to profit from the shaping which the final redactors gave the older material to transform traditional poetry into Sacred Scripture for the later generations of the faithful.1 In short, while the Psalms originated as human words to God and may still be used as such, they have been appropriated by the Church as God's word to humans. The Psalms are meant to be preached! According to Gerald H. Wilson, the "editorial 'center' of the final form of the Hebrew Psalter" is Book IV (Psalms 90-106).2 It is dominated by a collection of enthronement psalms, all of which address God as king or affirm that God reigns (Pss.