Exploring Psalm 80 As a Source for Matthew 25:31—46

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ezekiel 15.Pdf

The Vine Ezekiel 15 The Vine Introduction • For a few years I experimented with growing Concord grapes in our backyard. • It was a complete failure. The Vine Introduction • I cut down the vine, let it dry out and eventually burned it. • To be fair to the grapevine, it probably needed a bigger yard and more effort than I was able to give to it. The Vine Introduction • We shouldn’t blame the vine in this case. • The vine or vineyard is a theme that runs through much of the Bible. The Vine Introduction • Read Isaiah 5:1-7. The Vine Introduction • Read Isaiah 5:1-7. • The problem with the nation was its fruit – or its lack of good fruit, to be precise. • Ezekiel will elaborate on this theme. The Vine Ezekiel 15 The Vine Ezekiel 15 • The downfall of the nation began in the days of Isaiah. • It was completed in the days of Ezekiel. The Vine Ezekiel 15 • A vine that bears no fruit – or bad fruit – is truly worthless. • As Ezekiel points out, it’s wood isn’t really useful for anything except to burn. The Vine Ezekiel 15 • God appointed Israel to be a blessing to the nations. • Instead they were unfaithful and bore bad fruit. • Then the vine was burned and its wood became even more useless than it was at the beginning. The Vine Ezekiel 15 This situation is mentioned because of what actually happened to Jerusalem. The city was charred (partially burned) by the fire of the Babylonians in 597 BC, but survived. -

Psalm 80: an Exegetical Discussion on the Model of an Abandoned Child

Scriptura 119 (2020:1), pp. 1-15 http://scriptura.journals.ac.za http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/119-1-1454 PSALM 80: AN EXEGETICAL DISCUSSION ON THE MODEL OF AN ABANDONED CHILD Schalk Treurnicht Department Old and New Testament Stellenbosch University Abstract Psalm 80 uses a wide variety of metaphors to describe the way Israel saw God in their present context. This context is before the fall of Samaria to the Assyrians. It was a time of uncertainty, with many questions on God’s role in Israel’s future and God’s role in their present suffering. They may have asked, are they suffering because God has forgotten or abandoned them? Due to the uncertainty the psalm, which is a communal lament, asks God not to forget them and to return to them. This is done by referring to God’s past relationship with Israel, reminding God of the good parent-child relationship they once had. In Psalm 80 different metaphors work together to create this model of parent and child, with God portrayed not as a good parent, but rather a wicked one. But all is not lost, and Israel knows their lives can be saved by God choosing to return to them and to become, once again, the good parent, who keeps them safe. In this exegetical discussion on Psalm 80, I want to use these metaphors to help develop this model of Israel as an abandoned child and to conclude with the image that this portrays. The metaphor of Israel as child does not appear in Psalm 80, thus, the different metaphors that do appear, each say something about the relational experience Israel had with God. -

Rejection Imagery in the Synoptic Parables*

Bibliotheca Sacra 153 (July-September 1996) 308-31. Pt. 2 of 2 Copyright © 1996 by Dallas Theological Seminary. Cited with permission. REJECTION IMAGERY IN THE SYNOPTIC PARABLES* Karl E. Pagenkemper The first article in this two-part series looked at im- agery from Jesus' parables in the Synoptic Gospels that point to an eschatological rejection (thus the so-called "rejection" motif). Seven elements of imagery were examined: (1) "the furnace of fire," (2) the phrase "weeping and gnashing of teeth," (3) the im- agery of "outer darkness," (4) the motif of the shut door, (5) the phrase "I do not know you" (and its variations), (6) the verb dixo- tome<w, and (7) the nature of the rejection for those servants who did not invest their talents or minas. In each case the rejection signi- fied not simply a rejection from some of the privileges of the kingdom, but rather a complete rejection from the coming escha- tological kingdom. The ones rejected did not have any connec- tion with the salvation Jesus offered. This article discusses the criteria on which the eschatological judgments themselves are made. That is, what criteria did the master or king in each of these parables employ to determine ul- timate (i.e., eschatological) rejection or acceptance? TWO KEY PARABLES IN MATTHEW 13 The point of the parables of the Wheat and Tares and of the Dragnet in Matthew 13 is to teach about the nature of the kingdom of heaven and its mysteries). An issue these parables address is Karl E. Pagenkemper is Associate Professor of New Testament Studies, Interna- tional School of Theology, Arrowhead Springs, California. -

The Sheep and the Goats

The Sheep and the Goats What do Christians believe about ‘eschatology’? To do... In this passage from Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus uses imagery which would have As you read, been familiar to people in Israel at the time when he lived, of a shepherd dividing highlight what his animals into diff erent types. This passage is about what Christians call the passage ‘eschatology’, beliefs about the last days of the world. (‘Eschaton’ means about says will be the last things in ancient Greek.) Like most early Christians, Matthew was sure done by that the end of the world was very close. people who are righteous In this passage, it is Jesus who is speaking. (on the right) To do... and by the Who do others (on the “When the Son of Man comes as King and all the angels people need left), using a with him, he will sit on his royal throne, and the people to help others diff erent colour of all the nations will be gathered before him. Then he in order to for each. will divide them into two groups, just as a shepherd be called separates the sheep from the goats. He will put the ‘righteous’? righteous people on his right and the others on his left. Jesus often Then the King will say to the people on his right, ‘Come, referred to you that are blessed by my Father! Come and possess himself as ‘the the kingdom which has been prepared for you ever since Son of Man’. the creation of the world. I was hungry and you fed me, thirsty and you gave me a drink; I was a stranger and you received me in your homes, naked and you clothed ‘Righteous’ me; I was sick and you took care of me, in prison and means behaving you visited me.’ The righteous will then answer him, in a pure, fair and ‘When, Lord, did we ever see you hungry and feed you, or just way. -

The Prophets Speak on Forced Migration

THE PROPHETS SPEAK ON FORCED MIGRATION Press SBL A ncient Israel and Its Literature Thomas C. Römer, General Editor Editorial Board: Mark G. Brett Marc Brettler Cynthia Edenburg Konrad Schmid Gale A. Yee Press SBLNum ber 21 THE PROPHETS SPEAK ON FORCED MIGRATION Edited by Mark J. Boda, Frank Ritchel Ames, John Ahn, and Mark Leuchter Press SBL Press SBLAt lanta C opyright © 2015 by SBL Press A ll rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office,S BL Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The prophets speak on forced migration / edited by Mark J. Boda, Frank Ritchel Ames, John Ahn, and Mark Leuchter. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical Literature : Ancient Israel and its literature ; 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “In this collection of essays dealing with the prophetic material in the Hebrew Bible, scholars explore the motifs, effects, and role of forced migration on prophetic literature. Students and scholars interested in current, thorough approaches to the issues and problems associated with the study of geographical displacement, social identity ethics, trauma studies, theological diversification, hermeneutical strat- egies in relation to the memory, and the effects of various exilic conditions will find a valuable resource with productive avenues for inquiry”— Provided by publisher ISBN 978-1-62837-051-5 (paper binding : alk. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Ezekiel Chapters 4-24, God Warns People -Prophetic Messages -Symbolic Acts

Ezekiel Chapters 4-24, God warns people -prophetic messages -symbolic acts Initial warnings Chapters 4-7, Ezekiel dramatizes the coming siege and destruction of Jerusalem -chapter 4 dramatizes the siege -chapter 5 dramatizes the dispersion -chapter 6-7 says that human effort will not prevent the destruction DATES: June 597 Jehoiachin taken captive in the second captivity July 5 593 Ezekiel 1:1 September 17 592 Ezekiel 8:1 August 14 591 Ezekiel 20:1 January 15 588 Ezekiel 24:1 January 15 588 Beginning of the second siege (2 Kings 25:1) Ezekiel 26:1- 32:17 seven more messages July 18 586 Fall of Jerusalem January 8 585 Ezekiel 33:21 April 28 573 Ezekiel 40:1, the Millennial vision Chapters 4-11 · Ezekiel demonstrated the fact of the siege with the tablet and model city, the rationed food, laying on his side and shaving his hair. · He explained the reason for the siege. · He has now been given an other vision showing why judgment was necessary. Chapter 12 · The people can not understand. Their theology and understanding of God is so confused they can not make sense or believe Ezekiel’s words. · Ezekiel gives two more dramas to demonstrate. God says “They have eyes to see but do not see and ears to hear but do not hear, for they are a rebellious people.” (12:1) · The first drama is to dig through the wall of his house like an exile. (12:4) · The second drama is to eat food and shudder with fear (12:17) Ezekiel follows the two dramas with five messages: · 12:21-25– Message One– False Doctrinal statement “The days go by and every vision comes to nothing.” · 12:26-28– Message Two– False Doctrinal statement “The vision he sees is for many years from now.” · 13—Message Three– Foolish prophets condemned · 14:1-11—Message Four—Idolatrous Elders condemned · 14:12-23—Message Five—No one can save or intercede for Israel now Ezekiel 15-17 · Three proverbs · The useless vine · The adulterous wife · The great eagle A new series of messages that follow the second vision 12:1 A new series of messages. -

A Brief Note on Revelation 12:1 and 17:3-6

Modified 02/16/10 A Brief Note on Revelation 12:1 and 17:3-6 Copyright (c) 2010 by Frank W. Hardy, Ph.D. Within the literary model adopted by C. Mervyn Maxwell in God Cares , vol. 2, the book of Revelation divides into two parts and within these each main section has a counterpart in the other half of the book. Responsible exegesis demands that in any given case the two sections be studied together. 1 One such pair of sections involves chaps. 12 and 17. It is important that we compare these two chapters, not only because of the overall structure of Revelation, but because they are linked by a very clear example of parallel symbolism. In Rev 12 and again in Rev 17 John sees a woman. A woman is commonly used as a symbol for God's people, or in this case the church. 2 The one woman, described in Rev 12:1, is pure: A great and wondrous sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head. (Rev 12:1) The other woman, described in Rev 17:3-6a, is corrupt: (3) Then the angel carried me away in the Spirit into a desert. There I saw a woman sitting on a scarlet beast that was covered with blasphemous names and had seven heads and ten horns. (4) The woman was dressed in purple and scarlet, and was glittering with gold, precious stones and pearls. She held a golden cup in her hand, filled with abominable things and the filth of her adulteries. -

A Six Week Study in the Book of PSALMS Window to the Soul: a Six Week Study in the Book of Psalms

W t I o N SSOOUULL D t O h W e A Six Week Study in the book of PSALMS Window to the Soul: A Six Week Study in the Book of Psalms Since the inception of the Church, the psalms have been the sweet hymnbook by which God’s people have praised him for His goodness, kindness and Glory. They contain words of comfort in times of pain and encouragement for those who suffer. They are an example to us of how to be authentic in our struggles and honest in our failures, while always trusting Him to restore our souls. More than communicating a story, the psalms communicate experience, feeling, and emotion. As you study, remember that “The word of God is living and active…it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart” (Hebrews 4:12). God’s Word touches the depths of our souls, and leads us to the one who has all we need. Whether you are in a season of pain or sweet blessing, you can find rest as you read and study… The Psalms. Session 1: Psalm 100 The Elements of a Psalm Session 2: Psalm 100, Jonah 2 Psalms of Praise Session 3: Psalms 22, 80 Psalms of Lament Session 4: Psalm 51 Psalms of Penitence Session 5: Psalms 96, 99 Psalms of Kingship Session 6: Chapters 1, 19 Psalms of Wisdom 2 Session 1: Psalm 100 The Elements of a Psalm Helpful Hints: o The English word “psalms” is a Greek word simply spelled in Roman letters. The Greek word originally meant a striking or twitching of the fingers on a string. -

Lesson Booklet

Our God is YHWH A Study of Ezekiel’s Prophecy Trinity Bible Church Sunday School Fall 2019 Our God is YHWH A Study of Ezekiel’s Prophecy Now it came about in the thirtieth year, on the fifth day of the fourth month, while I was by the river Chebar among the exiles, the heavens were opened and I saw visions of God. Ezekiel 1:1 Trinity Bible Church Sunday School Fall, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Visions of God – An introduction to the study of Ezekiel . 3 Outline . 6 Schedule . 7 Memory Assignments. 8 Ezekiel 18:4; 33:11; 34:23-26; 36:24-27 Hymn . 9 “Before the Throne of God Above” Lesson 1: Visions of God. 10 Ezekiel 1-3 2: A Clay Tablet and a Barber’s Razor . 12 Ezekiel 4-5 3: Payday for Sin . 14 Ezekiel 6-7 4: Fury Without Pity! . 16 Ezekiel 8-9 5: Righteous Wrath and Sovereign Grace . 18 Ezekiel 10-11 6: Rebellion and Nonsense . 20 Ezekiel 12-14 7: Like Mother, Like Daughter! . 22 Ezekiel 15-17 8: The Soul Who Sins Shall Die! . 24 Ezekiel 18-20 9: A Drawn Sword, a Bloody City, and Two Harlots. 26 Ezekiel 21-23 10: The Siege Begins. 28 Ezekiel 24-26 11: A Lamentation for Tyre and the King of Tyre . 30 Ezekiel 27-28 12: The Monster in the Nile. 32 Ezekiel 29-30 13: The Lesson from Assyria. 34 Ezekiel 31-32 14: The Fall of Jerusalem . 36 Ezekiel 33-34 15: A Nation Regenerated. 38 Ezekiel 35-37 16: The Last Battle . -

Hell: Never, Forever, Or Just for Awhile?

TMSJ 9/2 (Fall 1998) 129-145 HELL: NEVER, FOREVER, OR JUST FOR AWHILE? Richard L. Mayhue Senior Vice President and Dean Professor of Theology and Pastoral Ministries The plethora of literature produced in the last two decades on the basic nature of hell indicates a growing debate in evangelicalism that has not been experienced since the latter half of the nineteenth century. This introductory article to the entire theme issue of TMSJ sets forth the context of the question of whether hell involves conscious torment forever in Gehenna for unbelievers or their annihilation after the final judgment. It discusses historical, philosophical, lexical, contextual, and theological issues that prove crucial to reaching a definitive biblical conclusion. In the end, hell is a conscious, personal torment forever; it is not “just for awhile” before annihilation after the final judgment (conditional immortality) nor is its final retribution “never” (universalism). * * * * * A few noted evangelicals such as Clark Pinnock,1 John Stott,2 and John Wenham3 have in recent years challenged the doctrine of eternal torment forever in hell as God’s final judgment on all unbelievers. James Hunter, in his landmark “sociological interpretation” of evangelicalism, notes that “. it is clear that there is a measurable degree of uneasiness within this generation of Evangelicals with the notion of an eternal damnation.”4 The 1989 evangelical doctrinal caucus “Evangelical Affirmations” surprisingly debated this issue. “Strong disagreements did surface over the position of annihilationism, a view that holds that unsaved souls 1Clark H. Pinnock, “The Conditional View,” in Four Views on Hell, ed. by William Crockett (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996) 135-66. -

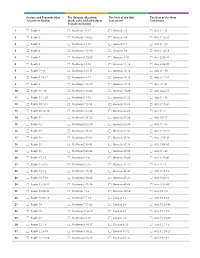

(Old Testament Books) the Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John

Psalms and Proverbs (Old The Gospels: Matthew, The Rest of the Old The Rest of the New Testament Books) Mark, Luke and John (New Testament Testament Testament Books) 1 Psalm 1 Matthew 1:1-17 Genesis 1-2 Acts 1:1-11 2 Psalm 2 Matthew 1:18-25 Genesis 3-4 Acts 1:12-26 3 Psalm 3 Matthew 2:1-12 Genesis 5-6 Acts 2:1-13 4 Psalm 4 Matthew 2:13-18 Genesis 7-8 Acts 2:14-28 5 Psalm 5 Matthew 2:19-23 Genesis 9-10 Acts 2:29-41 6 Psalm 6 Matthew 3:1-12 Genesis 11-12 Acts 2:42-47 7 Psalm 7:1-9 Matthew 3:13-17 Genesis 13-14 Acts 3:1-10 8 Psalm 7:10-17 Matthew 4:1-11 Genesis 15-16 Acts 3:11-26 9 Psalm 8 Matthew 4:12-17 Genesis 17-18 Acts 4:1-21 10 Psalm 9:1-10 Matthew 4:18-25 Genesis 19-20 Acts 4:22-37 11 Psalm 9:11-20 Matthew 5:1-12 Genesis 21-22 Acts 5:1-16 12 Psalm 10:1-11 Matthew 5:13-16 Genesis 23-24 Acts 5:17-42 13 Psalm 10:12-18 Matthew 5:17-20 Genesis 25-26 Acts 6:1-7 14 Psalm 11 Matthew 5:21-26 Genesis 27-28 Acts 6:8-15 15 Psalm 12 Matthew 5:27-30 Genesis 29-30 Acts 7:1-16 16 Psalm 13 Matthew 5:31-32 Genesis 31-32 Acts 7:17-32 17 Psalm 14 Matthew 5:33-37 Genesis 33-34 Acts 7:33-43 18 Psalm 15 Matthew 5:38-42 Genesis 35-36 Acts 7:44-60 19 Psalm 16 Matthew 5:43-48 Genesis 37-38 Acts 8:1-25 20 Psalm 17:1-5 Matthew 6:1-4 Genesis 39-40 Acts 8:26-40 21 Psalm 17:6-15 Matthew 6:5-15 Genesis 41-42 Acts 9:1-9 22 Psalm 18:1-6 Matthew 6:16-18 Genesis 43-44 Acts 9:10-19 23 Psalm 18:7-19 Matthew 6:19-24 Genesis 45-46 Acts 9:20-31 24 Psalm 18:20-29 Matthew 6:25-34