Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newcastle Fortresses

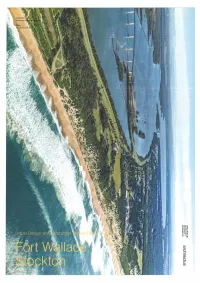

NEWCASTLE FORTRESSES Thanks to Margaret (Marg) Gayler for this article. During World War 2, Newcastle and the surrounding coast between Nelson Bay and Swansea was fortified by Defence forces to protect the east coast of New South Wales against the enemy, in case of attack from the Japanese between 1940 and 1943. There were the established Forts along the coastline, including Fort Tomaree, Fort Wallace (Stockton), Fort Scratchley, Nobbys Head (Newcastle East) and Shepherd’s Hill (Bar Beach) and Fort Redhead. The likes of Fort Tomaree (Nelson Bay), Fort Redhead (Dudley) and combined defence force that operated from Mine Camp (Catherine Hill Bay) came online during the Second World War to also protect our coast and industries like BHP from any attempt to bomb the Industries as they along with other smaller industries in the area helped in the war effort by supplying steel, razor wire, pith hats to our armed forces fighting overseas and here in Australia. With Australia at war overseas the Government of the day during the war years decided it was an urgency to fortify our coast line with not only the Army but also with the help of Navy and Air- Force in several places along the coast. So there was established a line of communication up and down the coast using all three defence forces involved. Starting with Fort Tomaree and working the way down to Fort Redhead adding a brief description of Mine Camp and the role of the RAAF, also mentioning where the Anti Aircraft placements were around Newcastle at the time of WW2. -

Shifting Sands at Stockton Beach Report

NEWCASTLE CITY COUNCIL SHIFTING SANDS AT STOCKTON BEACH Prepared by: Umwelt (Australia) Pty Limited Environmental and Catchment Management Consultants in association with June 2002 1411/R04/V2 Report No. 1411/R04/V2 Prepared for: NEWCASTLE CITY COUNCIL SHIFTING SANDS AT STOCKTON BEACH Umwelt (Australia) Pty Limited Environmental and Catchment Management Consultants PO Box 838 Toronto NSW 2283 Ph. (02) 4950 5322 Fax (02) 4950 5737 Shifting Sands at Stockton Beach Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1.1 2.0 PREVIOUS STUDIES AND REPORTS ................................. 2.1 2.1 BETWEEN WIND AND WATER (COLTHEART 1997) ............................2.1 2.2 NEWCASTLE HARBOUR INVESTIGATION (PWD (1963) REPORT 104)..........................................................................................2.2 2.3 NEWCASTLE HARBOUR – HYDROGRAPHIC HISTORY (MANLEY 1963) ......................................................................................2.2 2.4 LITTORAL DRIFT IN THE VICINITY OF NEWCASTLE HARBOUR (BOLEYN AND CAMPBELL CIRCA 1966) .............................................2.4 2.5 NEWCASTLE HARBOUR SILTATION INVESTIGATION (PWD 1969)...2.5 2.6 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT DEEPENING OF NEWCASTLE HARBOUR (MSB 1976) ...................................................2.6 2.7 FEASIBILITY STUDY ON NOURISHMENT OF STOCKTON BEACH (DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS 1978) ..........................................2.7 2.8 NEWCASTLE COASTLINE HAZARD DEFINITION STUDY (WBM -

Hunter Economic Zone

Issue No. 3/14 June 2014 The Club aims to: • encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat • encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity A Black-necked Stork pair at Hexham Swamp performing a spectacular “Up-down” display before chasing away the interloper - in this case a young female - Rod Warnock CONTENTS President’s Column 2 Conservation Issues New Members 2 Hunter Economic Zone 9 Club Activity Reports Macquarie Island now pest-free 10 Glenrock and Redhead 2 Powling Street Wetlands, Port Fairy 11 Borah TSR near Barraba 3 Bird Articles Tocal Field Days 4 Plankton makes scents for seabirds 12 Tocal Agricultural College 4 Superb Fairy-wrens sing to their chicks Rufous Scrub-bird Monitoring 5 before birth 13 Future Activity - BirdLife Seminar 5 BirdLife Australia News 13 Birding Features Birding Feature Hunter Striated Pardalote Subspecies ID 6 Trans-Tasman Birding Links since 2000 14 Trials of Photography - Oystercatchers 7 Club Night & Hunterbirding Observations 15 Featured Birdwatching Site - Allyn River 8 Club Activities June to August 18 Please send Newsletter articles direct to the Editor, HBOC postal address: Liz Crawford at: [email protected] PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Deadline for the next edition - 31 July 2014 Website: www.hboc.org.au President’s Column I’ve just been on the phone to a lady that lives in Sydney was here for a few days visiting the area, talking to club and is part of a birdwatching group of friends that are members and attending our May club meeting. -

Stockton Beach Taskforce

Stockton Beach Taskforce Meeting Minutes Details Meeting: Stockton Beach Taskforce Location: Microsoft Teams Date/time: Monday 12 October 2020 10:00am – 11:00am Chairperson: Rebecca Fox Deputy Secretary, Strategy, Delivery & Performance, Regional NSW Attendees Apologies · Chairperson: Rebecca Fox, Deputy · The Hon. John Barilaro, Deputy Premier Secretary, Strategy, Delivery & and Minister for Regional New South Performance, Regional NSW Wales, Industry and Trade · Alison McGaffin, Director Hunter & · Fiona Dewar, Executive Director, Central Coast, Regional NSW Regional Development, Regional NSW · Dr Chris Yeats, Executive Director, · Dr Kate Wilson, A/Deputy Secretary, Mining, Exploration and Geoscience Environment, Energy & Science Group · Sharon Molloy, Executive Director, · Craig Carmody, Chief Executive Officer, Biodiversity & Conservation, Energy & Port of Newcastle Science Group · Andrew Smith, Chief Executive Officer, · Councillor Nuatali Nelmes, Lord Mayor, Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council City of Newcastle · Joanne Rigby, Manager Assets & Observers Programs, City of Newcastle · Phil Watson, Principal Coastal Specialist, · Tim Crakanthorp MP, Member for Environment, Energy & Science Group Newcastle · Ross Cadell, Special Projects Director, Guests Port of Newcastle · Katie Ward, Senior Environmental · Dr Hannah Power, NSW Coastal Council Scientist, GHD · Barbara Whitcher, Chair, Stockton · Melissa Dunlop, Technical Director – Community Liaison Group Environment & Community, GHD · Ron Boyd, Community Representative · Valentina -

Executive Summary 5.5 Access and Circulation 33 9.3 Character and Context 78

» JJ --j (J) -j (J) ~ U JJ m (J) (J) o z o 11 --j I m u oJJ oU \ (J) m o o m m< 5 '\ u ~ \ m Z --j \ SPACKMAN MOSSOP~ architectus- Contents MICHAELS Executive summary 5.5 Access and circulation 33 9.3 Character and context 78 Introduction 11 5.6 Landscape 34 9.4 Issues to be resolved through detailed master planning 78 Introduction 13 5.7 Views 35 10 View assessment 80 1.1 The site 13 5.8 Coastal Erosion 36 10.1 Stockton Bridge 80 1.2 Purpose 01 this report 13 5.9 Built form 37 10.2 Fort Wallace Gun Emplacement Number 1 81 1.3 Objectives 01 the master plan 13 5.10 Consolidated constraints and opportunities 39 10.3 Fullerton Street North 82 1.4 The ream 13 10.4 Fullerton Street South 83 The proposal 2 Site context 15 10.5 Fort Scratchley 84 The master plan 43 2.1 Local context 15 10.6 Newcastle Ferry Wharf 85 6.1 The vision 43 2.2 Site analysis 15 10.7 Stockton Beach 86 6.2 Master plan principles 44 2.3 Existing built form 16 6.3 Indicative master plan 46 Conclusion 2.4 Stockton Peninsula History 18 Master plan public domain 51 11 Recommendations 90 2.5 Fort Wallace 19 7.1 Heritage Precinct 54 11.1 Planning controls 90 Strategic planning framework and controls 7.2 Community Park 56 Appendix A 3 Strategic planning context 22 7.3 Landscape Frontage 58 Master plan options 94 3.1 Hunter Regional Plan 22 7.4 Great Streets 60 Master plan options 95 3.2 Port Stephens Planning Strategy (PSPS) 2011 23 Master plan housing mix 66 3.3 Port Stephens Commercial and Industrial Lands Study 23 8.1 Dune apartments 68 Appendix B Local planning context 24 -

Newcastle Relocation Guide

Newcastle Relocation Guide Welcome to Newcastle Newcastle Relocation Guide Contents Welcome to Newcastle ......................................................................................................2 Business in Newcastle ......................................................................................................2 Where to Live? ...................................................................................................................3 Renting.............................................................................................................................3 Buying ..............................................................................................................................3 Department of Fair Trading...............................................................................................3 Electoral Information.........................................................................................................3 Local Council .....................................................................................................................4 Rates...................................................................................................................................4 Council Offices ..................................................................................................................4 Waste Collection................................................................................................................5 Stormwater .........................................................................................................................5 -

Talking About Grief a Better Path to Healing

OPINION & ANALYSIS 1 ONLINE COMMENT Pall over malls puts theherald.com.au Offroader debate A rally against the National Parks and Wildlife’s decision to ban four-wheel drives from planners on notice Stockton Beach attracted thousands of people. The story also attracted much heated The things department stores sell debate among our online are purchased easily on-line. So too readers. Phillip are clothes, shoes, jewellery, O’Neill cosmetics, travel, electronic goods, Do these people have no audio-visual products, sporting consideration for the goods and the like, the things that environmental health of Stockton NON-LIVING things die too, as stores in the malls specialise in. beach as well as other beaches Hunter residents know all too well. Fifth, Australians have taken on a like Redhead which are suffering Death has come to a steelworks, a cafe´ culture where they like their as a result of vehicles on them? shipyard, rail lines, town centres, coffee, snacks and casual dining to Archie churches, underground coal mines, take place in funky settings, often wool stores, department stores, with open air seating, and typically If only that many turned up on bookshops, licensed clubs, bank with interesting surrounds. cleanup Australia Day. branches, corner stores, a brewery, Try as it might, a Gruen-style mall Catdoglioncow textiles and clothing mills, can’t shed its introverted, stuck-in-a- aluminium smelters and post concrete box reality. A rally? Seriously guys, relax. Let offices. Some say that the malls can fight the place regenerate. Soon we might add shopping malls back. One strategy is called multi- SmallFeller to the list. -

Volunteers Remembering Our History

GET SOCIAL WITH US WINTER VOLUNTEERS WHAT’S ON NewcastleCouncil CityNewcastle CityNewcastle Did you know Newcastle City Council is one of the Art, culture, family fun - it's all here in Newcastle. For more information visit www.newcastle.nsw.gov.au 2017 Hunter's largest employers of volunteers? Our volunteer workforce includes We're committed to providing 10 June –20 August everyone from guides at Newcastle industry-leading volunteer induction THE PHANTOM SHOW Museum and Newcastle Art and training and we provide flexible Newcastle Art Gallery Gallery to wildlife carers at hours and rosters to ensure people Blackbutt Reserve and crews who put their hand up to help their 'Ghost who walks never can die' - an art working on our natural assets. community are happy in their exhibition celebrating pop art inspired by the long running Phantom comic book Council News Libraries and the Civic Playhouse position and perform to the series - was first shown in 1977. The Gallery's Community newsletter from Newcastle City Council are among the other venues best of their ability. 40th anniversary of exhibition returns to where volunteers play a key role. Visit newcastle.nsw.gov.au/ Newcastle as THE PHANTOM SHOW. They are also crucial to the many community for more information. committees and advisory panels 9 June – 11 June operating across the city. MELBOURNE Peter Trist, volunteer at Newcastle Region Library INTERNATIONAL COMEDY FESTIVAL ROADSHOW Civic Theatre Stand-up comedy extravaganza. BLACKBUTT RESERVE Buckle up Newcastle! The Melbourne Feeding times International Comedy Festival Roadshow is back on the bus, hitting the road to home 10.30am: Wombat feast deliver the freshest and funniest from 10.45am: Bird brunch Australia’s largest comedy festival. -

To the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate 19%

INDEX TO THE NEWCASTLE MORNING HERALD AND MINERS' ADVOCATE 19% Published by NKWrASTLK PUBLIC LIBRARY The Council of the City of Newcastle New South wales, Australia 1984 N.M.H. INDEX 1.1%6 ABATTCaES ACCIDENTS MiD FATALITIES (Con't) Move to comlj&t erosion on abattoir Porter took own life, says coroner land 10.1:2 7.12:4 Made £?8,000 last year : costs cut Fell from train : father of Peg Seattle £55,OOC frcm abattoir profit 2.5:2 Double meat storage : new chambers dead 23.12:1 at abattoir 12.6:2 Five die ; holiday accidents 27.12:1 Freezing plant opened (photograph) AGRICULTURE 12.6:4 Seek legal opinion on big bonus Thrips damage tomato crops 5.1:4 27.6:-2 Would like U.S. trip : Wallalong Long leave fcr abattoir workers 22.8:2 farmer a finalist 2.2:2 Cour-try killing "best scheme" 2-4-.8:4 Premifei- spoke to farmers as "man on the Heavy cattle at abattoir 11.9:2 land" 27.4:4 Abattoir has record day 12.9:2 Upper Hunter farmer holds Italian Judge critical : says award misused diploma 5.8 J at abattoir -15.10:4 Hunter, Manning important for stock- Soap-making tests at abattoir 11.^2:2 fattening 20.8:2 "Newcastle only abattoir making profit" Unirrigated potato crops failure 11.12:2 again 12.10:4 Maitland abattoir made profit each year Conditions slip in Hunter Di.sl.idct 15.12:2 1.11:2 Maitland abattoir finances 14.12:4 Farmers warned ; poisonous weed in Favour abattoir at Cessncck 18.12:2 millet seed 1.11:2 Lack of water in Hunter causes concern ABORIGINES, Australian 9.11:10 "Cultivate with care or soil will Aborigines will ask Mr Chifley -

Destination Management Plan for Port Stephens (Diagnostic Report)

Destination Management Plan for Port Stephens (Diagnostic Report) Prepared by Tars Bylhouwer for Destination Port Stephens May 2013 INDEX PREFACE __________________________________________________________________ 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ______________________________________________________ 5 WHERE ARE WE/ DESTINATION OVERVIEW _____________________________________ 7 AREA OVERVIEW ______________________________________________________7 STRUCTURE OF TOURISM IN PORT STEPHENS _______________________________8 Organisational ______________________________________________________8 Relationships _______________________________________________________8 Resources __________________________________________________________9 Visitor Servicing _____________________________________________________9 1. Visitor Information Centres (VIC’s) ________________________________9 2. Online Bookings _____________________________________________ 11 3. Digital Information ___________________________________________ 11 4. Other _____________________________________________________ 11 SIGNIFICANCE OF PORT STEPHENS AS A DESTINATION ______________________ 12 Quantitative Research ______________________________________________ 12 1. Brand Health Tracking (BHT) ___________________________________ 12 2. Hunter Valley Research Foundation (HVRF) Omnibus survey: 2000 and 2002 ______________________________________________________ 13 3. 2012 UTS undergraduate survey (Kim Trinh) _______________________ 13 4. Port Stephens Beachside Holiday Park (PSBHP) study 2010 ___________ 14 -

Hunter Estuary Landmark Dates

CRITICAL EVENTS AND DEVELOPMENT AFFECTING THE HUNTER ESTUARY SINCE 1970 Max Maddock Updated 30 December 2003 During January – February 2002, the community was made aware of proposals for industrial development in the Hunter Estuary by a series of articles in the Newcastle Herald. The proposed developments have the potential to destroy the estuary as a migratory wader habitat and as a Wetland of International Importance listed as a Ramsar site under the Ramsar Convention. They will have serious adverse effects on the complex ecology of the whole of the estuary and associated flood plain wetlands, resulting in changes to flood regime and damage to the fishing industry. In February 2003, during a pre-election visit by the Premier of NSW to Newcastle a concept plan for development of the port environs of the Hunter Estuary (KBR 2003), with even worse potential impacts, was released. Community consultation on the plan was promised. This document gives an analysis of historical events and documents relevant to developments and proposals for developments in the Hunter Estuary for the period 1970-2003. A summary of critical landmarks leading up to the recent industrial development proposals and the Newcastle Port Environs Concept Proposal and subsequent events, is given in the Appendix. The list is by no means exhaustive, but provides an insight into critical issues associated with the proposals. Government Environmental Policies, Acts and Legislation Both the NSW and Federal Governments have developed a set of key policies, Acts and legislation governing decision making on development proposals in wetland settings. In issues associated with wetlands of international importance, the State Government is bound to comply with the Federal requirements in addition to its own requirements, ensuring Ecologically Sustainable Development has been accepted by both governments as the fundamental underlying principle guiding assessment of development proposals. -

OFFICIAL POCKET GUIDE and MAP and GUIDE POCKET OFFICIAL Bars with Spectacular Harbour Views

visitnewcastle.com.au Welcome to Newcastle Discover See & Do Newcastle is one of Australia's oldest and most Despite having inspired Lonely Planet's admiration, interesting cities,offering a blend of new and old Newcastle is yet to be detected by the mass tourism architecture, a rich indigenous history, and one of radar. The seaside city of Newcastle is a great holiday the busiest ports in the world. The land and waters destination with a rich history, quirky arts culture and a of Newcastle are acknowledged as the country of thriving dining and shopping scene. Embark on one of the the Awabakal and Worimi peoples, whose culture many self-guided walking tours or learn how to surf. Spot is celebrated in community events, place naming, local marine life aboard Moonshadow Cruises or Nova signage and artworks. To learn more about Newcastle’s Cruises or get up close to Australian animals at Blackbutt history, take a walk through Newcastle Museum, 5 ways to experience Newcastle like a local Reserve, 182 hectares of natural bushland where you can walk the trails and discover the wildlife. Take a family day Eat & Drink Newcastle Maritime Centre, or visit Fort Scratchley Get your caffeine fix - Over the past few years, Newcastle Historic Site, at its commanding position guarding out to swing and climb like Tarzan at Tree Top Adventure Newcastle has an emerging food scene that makes it has created a coffee culture that gives Melbourne a run for the Hunter River Estuary. Explore Christ Church Park, or for something more relaxing, pack up the picnic an appealing spot to indulge in quality food and wine.