Hunter Estuary Landmark Dates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hunter Estuary Wetlands Ramsar Site Is Located in the Lower Hunter River Estuary, Along the Central Coast of New South Wales

The Hunter Estuary Wetlands Ramsar site is located in the lower Hunter River estuary, along the central coast of New South Wales. Tomago Wetland lies immediately to the west of Fullerton Cove. As part of the Williamtown - Long Bight - Tomago Drainage Scheme, the levee bank, ring drain and other internal drains were enlarged by the NSW Public Works Department between 1968 and 1980 (MacDonald et al. 1997). These engineering works, including the installation of floodgates at the tidal boundary, ensured that tidal waters are excluded from Tomago Wetlands (i.e. the site drains via one- way tidal floodgates). The drainage and exclusion of tidal waters within Tomago Wetland degraded the salt marsh ecosystem and fostered the growth of non-salt marsh species. Lowering of the groundwater table also oxidised sub-surface acid sulfate soils causing soil acidification. Grazing and other users of the site further degraded the previous ecosystem and reduced migratory wading bird habitat. Tidal inundation was restored to the western portion of the site in 2007, with a culvert restricting exchange between the eastern and western sides installed as part of these works. As such the western half of Tomago Wetlands remains in an unrestored state. This study aimed to determine the impact of restoring tidal exchange at the eastern floodgates of Tomago Wetlands. Benefits of tidal restoration would include increased fish habitat, reduced weed growth, increase salt marsh habitat, improved bird roosting and feeding conditions and minimise acid sulfate soil impacts. Two-Dimensional (2D) numerical modelling hydrodynamic tools were used to simulate the reintroduction of tidal exchange at the site and to determine the optimal configuration of on-ground structures. -

Kooragang Wetlands: Retrospective of an Integrated Ecological Restoration Project in the Hunter River Estuary

KOORAGANG WETLANDS: RETROSPECTIVE OF AN INTEGRATED ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION PROJECT IN THE HUNTER RIVER ESTUARY P Svoboda Hunter Local Land Services, Paterson NSW Introduction: At first glance, the Hunter River estuary near Newcastle NSW is a land of contradictions. It is home to one of the world’s largest coal ports and a large industrial complex as well as being the location of a large internationally significant wetland. The remarkable natural productivity of the Hunter estuary at the time of European settlement is well documented. Also well documented are the degradation and loss of fisheries and other wildlife habitat in the estuary due to over 200 years of draining, filling, dredging and clearing (Williams et al., 2000). However, in spite of extensive modification, natural systems of the estuary retained enough value and function for large areas to be transformed by restoration activities that aimed to show industry and environmental conservation could work together to their mutual benefit. By establishing partnerships and taking a collaborative and adaptive approach, the project was able to implement restoration and related activities on a landscape basis, working across land ownership and management boundaries (Kooragang Wetland Rehabilitation Project, 2010). The Kooragang Wetland Rehabilitation Project (KWRP) was launched in 1993 to help compensate for the loss of fisheries and other wildlife habitat at suitable sites in the Hunter estuary. This paper revisits the expectations and planning for the project as presented in a paper to the INTECOL’s V international wetlands conference in 1996 (Svoboda and Copeland, 1998), reviews the project’s activities, describes outcomes and summarises issues faced and lessons learnt during 24 years of implementing a large, long-term, integrated, adaptive and community-assisted ecological restoration project. -

Motion 2- RAMSAR Listing Menindee Lakes.Pdf

Motion 2 Region 4 – Central Darling Shire Council Motion: That the MDA calls on Basin Governments to endorse the Menindee Lakes, or a portion of the Lake system to be listed as a Ramsar site, in further consultation with the community. Objective: To protect the Menindee Lakes as a wetlands of cultural and ecological significance and to preserve and to conserve, through wise use and management, those areas of the system identified as appropriate for listing. Key Arguments: • In 2010-11 there were attempts to have a proportion of the Menindee Lakes recognised as being listed as a Ramsar site. Regional Development Australia Far West NSW (RDAFW) invested resources and efforts into having a proportion of the Lakes listed as a Ramsar Sites on behalf of Central Darling Shire and the Far West region. At this point in time, the State Government recognised the significance of the Menindee Lakes, however they were not able to support the project with the position of the Murray Darling Basin plan at the time. • Ramsar Convention and signing on Wetlands took place on 2 February 1971 at the small Iranian town named Ramsar and came into force on 21 December 1975. Since then, the Convention on Wetlands has been known as the Ramsar Convention. The Ramsar Convention's intentions is to halt the worldwide loss of wetlands and to conserve, through wise use and management, of those that remain. This requires international cooperation, policy making, capacity building and technology transfer. • Under the Ramsar Convention, a wide variety of natural and human-made habitat types ranging from rivers to coral reefs can be classified as wetlands. -

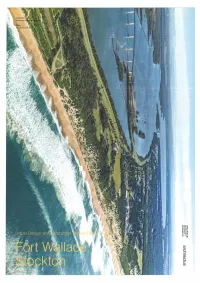

Newcastle Fortresses

NEWCASTLE FORTRESSES Thanks to Margaret (Marg) Gayler for this article. During World War 2, Newcastle and the surrounding coast between Nelson Bay and Swansea was fortified by Defence forces to protect the east coast of New South Wales against the enemy, in case of attack from the Japanese between 1940 and 1943. There were the established Forts along the coastline, including Fort Tomaree, Fort Wallace (Stockton), Fort Scratchley, Nobbys Head (Newcastle East) and Shepherd’s Hill (Bar Beach) and Fort Redhead. The likes of Fort Tomaree (Nelson Bay), Fort Redhead (Dudley) and combined defence force that operated from Mine Camp (Catherine Hill Bay) came online during the Second World War to also protect our coast and industries like BHP from any attempt to bomb the Industries as they along with other smaller industries in the area helped in the war effort by supplying steel, razor wire, pith hats to our armed forces fighting overseas and here in Australia. With Australia at war overseas the Government of the day during the war years decided it was an urgency to fortify our coast line with not only the Army but also with the help of Navy and Air- Force in several places along the coast. So there was established a line of communication up and down the coast using all three defence forces involved. Starting with Fort Tomaree and working the way down to Fort Redhead adding a brief description of Mine Camp and the role of the RAAF, also mentioning where the Anti Aircraft placements were around Newcastle at the time of WW2. -

Anthony Kelly, Guinness World Record

ANTHONY KELLY, GUINNESS WORLD RECORD ........................................................................ 3125 ARMIDALE AND DISTRICT WOMEN'S CENTRE ........................................................................... 3163 BAULKHAM HILLS CHRISTMAS CARD COMPETITION ............................................................. 3125 BAYS PRECINCT URBAN RENEWAL PROGRAM ......................................................................... 3134 BUDGET ESTIMATES AND RELATED PAPERS ................................................................... 3119, 3152 BULAHDELAH DISTRICT SOLDIERS MEMORIAL GATES 1914-1918 ....................................... 3166 BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE .................................................................................. 3090, 3117, 3142, 3143 CALLAGHAN COLLEGE WALLSEND SOLAR CAR EVENT ........................................................ 3125 CARAVAN REGISTRATION COSTS ................................................................................................. 3117 CHESTER HILL BAPTIST CHURCH EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY ........................................ 3124 COAL DUST AND AIR QUALITY ...................................................................................................... 3113 COMMUNITY RECOGNITION STATEMENTS ................................................................................ 3123 CONSIDERATION OF MOTIONS TO BE ACCORDED PRIORITY ................................................ 3146 CRIME COMMISSION LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2014................................................ -

Shifting Sands at Stockton Beach Report

NEWCASTLE CITY COUNCIL SHIFTING SANDS AT STOCKTON BEACH Prepared by: Umwelt (Australia) Pty Limited Environmental and Catchment Management Consultants in association with June 2002 1411/R04/V2 Report No. 1411/R04/V2 Prepared for: NEWCASTLE CITY COUNCIL SHIFTING SANDS AT STOCKTON BEACH Umwelt (Australia) Pty Limited Environmental and Catchment Management Consultants PO Box 838 Toronto NSW 2283 Ph. (02) 4950 5322 Fax (02) 4950 5737 Shifting Sands at Stockton Beach Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1.1 2.0 PREVIOUS STUDIES AND REPORTS ................................. 2.1 2.1 BETWEEN WIND AND WATER (COLTHEART 1997) ............................2.1 2.2 NEWCASTLE HARBOUR INVESTIGATION (PWD (1963) REPORT 104)..........................................................................................2.2 2.3 NEWCASTLE HARBOUR – HYDROGRAPHIC HISTORY (MANLEY 1963) ......................................................................................2.2 2.4 LITTORAL DRIFT IN THE VICINITY OF NEWCASTLE HARBOUR (BOLEYN AND CAMPBELL CIRCA 1966) .............................................2.4 2.5 NEWCASTLE HARBOUR SILTATION INVESTIGATION (PWD 1969)...2.5 2.6 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT DEEPENING OF NEWCASTLE HARBOUR (MSB 1976) ...................................................2.6 2.7 FEASIBILITY STUDY ON NOURISHMENT OF STOCKTON BEACH (DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS 1978) ..........................................2.7 2.8 NEWCASTLE COASTLINE HAZARD DEFINITION STUDY (WBM -

Hunter Economic Zone

Issue No. 3/14 June 2014 The Club aims to: • encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat • encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity A Black-necked Stork pair at Hexham Swamp performing a spectacular “Up-down” display before chasing away the interloper - in this case a young female - Rod Warnock CONTENTS President’s Column 2 Conservation Issues New Members 2 Hunter Economic Zone 9 Club Activity Reports Macquarie Island now pest-free 10 Glenrock and Redhead 2 Powling Street Wetlands, Port Fairy 11 Borah TSR near Barraba 3 Bird Articles Tocal Field Days 4 Plankton makes scents for seabirds 12 Tocal Agricultural College 4 Superb Fairy-wrens sing to their chicks Rufous Scrub-bird Monitoring 5 before birth 13 Future Activity - BirdLife Seminar 5 BirdLife Australia News 13 Birding Features Birding Feature Hunter Striated Pardalote Subspecies ID 6 Trans-Tasman Birding Links since 2000 14 Trials of Photography - Oystercatchers 7 Club Night & Hunterbirding Observations 15 Featured Birdwatching Site - Allyn River 8 Club Activities June to August 18 Please send Newsletter articles direct to the Editor, HBOC postal address: Liz Crawford at: [email protected] PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Deadline for the next edition - 31 July 2014 Website: www.hboc.org.au President’s Column I’ve just been on the phone to a lady that lives in Sydney was here for a few days visiting the area, talking to club and is part of a birdwatching group of friends that are members and attending our May club meeting. -

REPORTED in the MEDIA Newspapers

REPORTED IN THE MEDIA Newspapers • Mortgage Interest Rates The Age , Banks Dudding Customers for Years, 4/10/2012, Front page . The Sydney Morning Herald, The Big Banks Take with One Hand - and the Other , 4/10/ 2012, p.2 The results of my research on the RBA’s rate cuts and the asymmetric behaviour of Big 4 banks in setting their mortgage rates also attracted widespread media attention on 4 October 2012: Melbourne Weekly, Brisbane Times, Stock & Land, Stock Journal, The West Australian, Brisbane Times, Finders News, Southwest Advertiser, Daily Life, Dungog Chronicle, Western Magazine, Frankston Weekly, The Mercury , Sun City News . http://theage.com.au/business/the-big-banks-take-with-one-hand--and-the-other-20121003- 26ztm.html http://smh.com.au/business/the-big-banks-take-with-one-hand--and-the-other-20121003-26ztm.html http://nationaltimes.com.au/business/the-big-banks-take-with-one-hand--and-the-other-20121003- 26ztm.html • University Research Performance Just a Matter of Time Before Universities Take Off, Australian Financial Review , 31/7/2006, p.34 Melbourne on a High, The Australian , 26/7/2006, p.23. Smaller Universities Top of their Class, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20/7/2005, p.10. Sutton's New Vision, Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong), 21/7/2005, p.7. Uni Gets Top Grade, The Newcastle Herald, 20/7/2005, p. 21. • Petrol Prices Call for Bowser Boycott, The Telegraph , 28/3/2013, p.3. Pump your Pockets, Herald Sun , 28/3/2013, p.9. Drivers Urged to Fill Up on Cheaper Days, Courier Mail , 28/3/2013, p.11 Reward to Eagle-Eyed Motorists, Courier Mail, Brisbane, 10/8/2001, p.5. -

Stockton Beach Taskforce

Stockton Beach Taskforce Meeting Minutes Details Meeting: Stockton Beach Taskforce Location: Microsoft Teams Date/time: Monday 12 October 2020 10:00am – 11:00am Chairperson: Rebecca Fox Deputy Secretary, Strategy, Delivery & Performance, Regional NSW Attendees Apologies · Chairperson: Rebecca Fox, Deputy · The Hon. John Barilaro, Deputy Premier Secretary, Strategy, Delivery & and Minister for Regional New South Performance, Regional NSW Wales, Industry and Trade · Alison McGaffin, Director Hunter & · Fiona Dewar, Executive Director, Central Coast, Regional NSW Regional Development, Regional NSW · Dr Chris Yeats, Executive Director, · Dr Kate Wilson, A/Deputy Secretary, Mining, Exploration and Geoscience Environment, Energy & Science Group · Sharon Molloy, Executive Director, · Craig Carmody, Chief Executive Officer, Biodiversity & Conservation, Energy & Port of Newcastle Science Group · Andrew Smith, Chief Executive Officer, · Councillor Nuatali Nelmes, Lord Mayor, Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council City of Newcastle · Joanne Rigby, Manager Assets & Observers Programs, City of Newcastle · Phil Watson, Principal Coastal Specialist, · Tim Crakanthorp MP, Member for Environment, Energy & Science Group Newcastle · Ross Cadell, Special Projects Director, Guests Port of Newcastle · Katie Ward, Senior Environmental · Dr Hannah Power, NSW Coastal Council Scientist, GHD · Barbara Whitcher, Chair, Stockton · Melissa Dunlop, Technical Director – Community Liaison Group Environment & Community, GHD · Ron Boyd, Community Representative · Valentina -

Executive Summary 5.5 Access and Circulation 33 9.3 Character and Context 78

» JJ --j (J) -j (J) ~ U JJ m (J) (J) o z o 11 --j I m u oJJ oU \ (J) m o o m m< 5 '\ u ~ \ m Z --j \ SPACKMAN MOSSOP~ architectus- Contents MICHAELS Executive summary 5.5 Access and circulation 33 9.3 Character and context 78 Introduction 11 5.6 Landscape 34 9.4 Issues to be resolved through detailed master planning 78 Introduction 13 5.7 Views 35 10 View assessment 80 1.1 The site 13 5.8 Coastal Erosion 36 10.1 Stockton Bridge 80 1.2 Purpose 01 this report 13 5.9 Built form 37 10.2 Fort Wallace Gun Emplacement Number 1 81 1.3 Objectives 01 the master plan 13 5.10 Consolidated constraints and opportunities 39 10.3 Fullerton Street North 82 1.4 The ream 13 10.4 Fullerton Street South 83 The proposal 2 Site context 15 10.5 Fort Scratchley 84 The master plan 43 2.1 Local context 15 10.6 Newcastle Ferry Wharf 85 6.1 The vision 43 2.2 Site analysis 15 10.7 Stockton Beach 86 6.2 Master plan principles 44 2.3 Existing built form 16 6.3 Indicative master plan 46 Conclusion 2.4 Stockton Peninsula History 18 Master plan public domain 51 11 Recommendations 90 2.5 Fort Wallace 19 7.1 Heritage Precinct 54 11.1 Planning controls 90 Strategic planning framework and controls 7.2 Community Park 56 Appendix A 3 Strategic planning context 22 7.3 Landscape Frontage 58 Master plan options 94 3.1 Hunter Regional Plan 22 7.4 Great Streets 60 Master plan options 95 3.2 Port Stephens Planning Strategy (PSPS) 2011 23 Master plan housing mix 66 3.3 Port Stephens Commercial and Industrial Lands Study 23 8.1 Dune apartments 68 Appendix B Local planning context 24 -

Hunter Wetlands National Park Plan of Management

NSW NATIONAL PARKS & WILDLIFE SERVICE Hunter Wetlands National Park Plan of Management environment.nsw.gov.au © 2020 State of NSW and Department of Planning, Industry and Environment With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Department of Planning, Industry and Environment are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (DPIE) has compiled this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. DPIE shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. All content in this publication is owned by DPIE and is protected by Crown Copyright, unless credited otherwise. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons. DPIE asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Department of Planning, Industry and Environment 2020. Cover photo: Hunter Wetlands National Park. D Benson/DPIE This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for Energy and Environment on 23 March 2020. -

Munibung Musings

Munibung Musings No.2 - Autumn 2019 Stop Press Proposed conservation park has been placed on the market The Newcastle Herald (9.3.2019) carried the story in the Commercial Property section of Domain, under the The pitch to headline: Munibung Hill being sold developers by Renee Valentine ‘A superb development “A Speers Point property of around 80 hectares of land at 1A opportunity now and Raymond Street is being marketed by Barry Price, Ray White into the future.’ Newcastle and Lake Macquarie, and John Parnham, of Ray White Commercial. That can only mean a challenge to the current area- It has development application approval for 115 residential lots on a small part of the site, which is bordered by Boolaroo, Zoned E2 to allow for more Warners Bay and Macquarie Hills. streets and housing. That would be another case of Is this what we can look forward to on The landmark property has been held by its current owners for Munibung Hill in the future as the around 80 years and enjoys extensive views of Lake Macquarie “mission creep” and that result of this 80 ha sell off? and Mount Sugarloaf. would mean in addition to the approved 115 lots on 11 ha, another 721 residential “It’s a very large piece of land and twice the size of most of the lots on 69 ha, in place of this important conservation suburbs around it," Mr Price said. “It’s got some outstanding lake views from many many places and is 800 metres from the and wildlife area. Urban forest destroyed.