Integrated Livelihood Development and Human Security Strategy Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Data Table S1 the Reference and Number of Pseudo

Supplementary Data Table S1 The reference and number of pseudo informants of medicinal plants used to treat Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among the Karen ethnic minority in Thailand. Scientific Family No. Pseudo Part of Use Preparation Application ICPC-2 2nd Level Refere Name informants nce Acanthus ACANTHACEAE 1 Leaves Decoction Oral Muscle pain [1] montanus ingestion (Nees) T. Anderson Acmella oleracea ASTERACEAE 1 Roots Alcoholic Oral Muscle pain [1] (L.) R.K. Jansen infusion ingestion Ageratina ASTERACEAE 1 Leaves Burning Poultices Muscle pain [2] adenophora (Spreng.) R.M. King and H. Rob. Ageratum ASTERACEAE 1 Whole Decoction Oral Back [3] conyzoides L. plants ingestion symptom/compla int, Flank/axilla symptom/compla int Aglaia lawii MELIACEAE 1 Leaves Decoction Bath, oral Muscle pain [4] (Wight) C.J. ingestion Saldanha Alpinia galanga ZINGIBERACEAE 1 Roots Decoction Oral Back [5] (L.) Willd. ingestion symptom/compla int, Flank/axilla symptom/compla int Alpinia ZINGIBERACEAE 1 Roots Decoction Bath, oral Muscle pain [2] roxburghii ingestion Sweet Alstonia APOCYNACEAE 1 Bark Water Oral Muscle pain [6] macrophylla infusion ingestion Wall. ex G. Don Alstonia rostrata APOCYNACEAE 1 Bark Decoction, Oral Muscle pain [2] C.E.C. Fisch. water ingestion infusion Anredera BASELLACEAE 1 Bulbil Cook Eaten as Back [3] cordifolia (Ten.) food symptom/compla Steenis int, Flank/axilla symptom/compla int Antidesma EUPHORBIACEAE 1 Roots Decoction Oral Back [5] bunius (L.) ingestion symptom/compla Spreng. int, Flank/axilla symptom/compla int Asparagus ASPARAGACEAE 2 Roots, whole Decoction Bath, oral Muscle pain [1,5] filicinus Buch.- plants ingestion Ham. ex D. Don Baccaurea EUPHORBIACEAE 1 Roots Decoction Oral Back [5] ramiflora Lour. -

Interbasin Transfers Within Thailand*: the Salween/Luam/Ping/Chao Phraya Projects

Interbasin Transfers within Thailand*: the Salween/Luam/Ping/Chao Phraya projects An interbasin transfer is an engineering scheme that diverts some or all of the discharge from a discrete river basin (or from a sub-basin within a larger catchment) LQWRDVWUHDPGUDLQLQJDFRPSOHWHO\GLͿHUHQWEDVLQRU sub-basin, thereby agumenting the latters’ discharge by a volume equivalent to that diminished from the source catchment. The two main motivations for interbasin transfers are: LQK\GURSRZHUHQJLQHHULQJWRWDNHDGYDQWDJHRIWKH UHFHLYLQJVWUHDPV·WRSRJUDSK\WRVLJQLÀFDQWO\LQFUHDVH the hydrostatic head of the release from a reservoir in the original catchment, through a canal or tunnel to a generating facility in the receiving catchment that is much lower in relative elevation than would be practica- ble within the source basin. The result is a much higher energy yield, for a given dam+reservoir, with only a relatively minor increase in overall capital investment. 7KH6DOZHHQ 7KDQOZLQLQ%XUPHVH HVWXDU\DW0\DZODPD\Q0\DQPDUDQLPDWHGÁ\WKURXJK The Chao Phraya delta at Krungthep (Bangkok) The best example in our study area is the Nam Theun 2 project in the Lao PDR, which diverts some 300 cumecs of water from the Theun-Kading basin into the Xe Bang Fai (XBF) basin, via both excavated new canals and existing XBF tributaries. LQZDWHUUHVRXUFHVPDQDJHPHQWIRUEHWWHUPHHWLQJ both M&I and irrigation demands; where the existing EDVLQ·VDJJUHJDWHGLVFKDUJHLVLQVXFLHQWWRIXOÀO essential needs in dry-season or drought conditions. As seen in the instant case (the Salween-Chao Phraya proposal), the energy requirements of interbasin transfer schemes of this category —where the source catchment is at a lower elevation than the receiving basin may be Oblique space imagery and schematic speed-drDwing of Thanlwin/Salween-Luam-Ping/Chao Phraya interbasin transfer components TXLWHH[WUHPHEXWWKHFRVWEHQHÀWHFRQRPLFVRISXPSLQJ Coordinates: 17°4955N 97°4131E Yuam River From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia vs. -

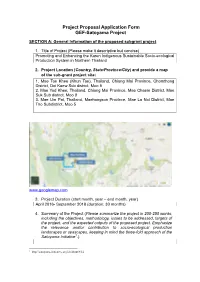

Project Proposal Application Form GEF-Satoyama Project

Project Proposal Application Form GEF-Satoyama Project SECTION A: General Information of the proposed subgrant project 1. Title of Project (Please make it descriptive but concise) Promoting and Enhancing the Karen Indigenous Sustainable Socio-ecological Production System in Northern Thailand 2. Project Location (Country, State/Province/City) and provide a map of the sub-grant project site) 1. Mae Tae Khee (Khun Tae), Thailand, Chiang Mai Province, Chomthong District, Doi Kaew Sub district, Moo 5 2. Mae Yod Khee, Thailand, Chiang Mai Province, Mae Chaem District, Mae Suk Sub district, Moo 9 3. Mae Um Pai, Thailand, Maehongson Province, Mae La Noi District, Mae Tho Subdistrict, Moo 5 www.googlemap.com 3. Project Duration (start month, year – end month, year) April 2016- September 2018 (duration: 30 months) 4. Summary of the Project (Please summarize the project in 200-250 words, including the objectives, methodology, issues to be addressed, targets of the project, and the expected outputs of the proposed project. Emphasize the relevance and/or contribution to socio-ecological production landscapes or seascapes, keeping in mind the three-fold approach of the Satoyama Initiative1.) 1 http://satoyama-initiative.org/en/about/#3.2 The project aims to support three Karen communities to become a model of community-based sustainable development by building on their traditional knowledge and natural resource management systems and combining it with innovative and technologically advanced community-controlled mapping, monitoring and information systems and with increased economic productivity both for human wellbeing and for biodiversity. It will also counter threats to endangered species, develop recovery plans and address invasive alien species. -

Shifting Cultivation Livelihood and Food Security

Shifting Cultivation, Livelihood and Food Security New and Old Challenges for Indigenous Peoples in Asia Editor Christian Erni Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and International Work Group For Indigenous Affairs and Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact Bangkok, 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), or of the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) or of the Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO, or IWGIA or AIPP in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO, or IWGIA or AIPP. 978-92-5-108761-9 (FAO) © FAO, IWGIA and AIPP, 2015 FAO, IWGIA and AIPP encourage the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO, IWGIA and AIPP as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s, IWGIA’s and AIPP’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. -

Mae Hong Son

Mae Hong Son 24 hrs. Everyday Tourist information by fax available 24 hrs. e-mail: [email protected] www.tourismthailand.org 61-03-110 poklang Mae Hong Son eng i_coated 61-03-110 Cover Mae Hong Son61-03-110 eng i_coated.indd pokna 3 Mae Hong Son eng i_coated 5/4/2561 BE 21:24 Mae Hong Son Mae Hong Son 61-03-110_Incover 003-046 Mae Hong61-03-110 Son eng new27-4_G-Coated.indd naipokna 2Mae Hong Son eng i_coated27/4/2561 BE 08:49 61-03-110 naipokna Mae Hong Son eng i_coated 61-03-110 Incover 003-046 Mae Hong Son eng i_coated.indd 3 5/4/2561 BE 21:25 Wat To Phae 61-03-110 Incover 003-046 Mae Hong Son eng i_coated.indd 4 5/4/2561 BE 21:26 CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 7 ATTRACTIONS 9 Amphoe Mueang Mae Hong Son 9 Amphoe Pang Mapha 16 Amphoe Pai 16 Amphoe Khun Yuam 19 Amphoe Mae La Noi 20 Amphoe Mae Sariang 20 Amphoe Sop Moei 21 EVENTS & FESTIVALS 22 LOCAL PRODUCTS 24 INTERESTING ACTIVITIES 25 Rafting along the Pai River 25 Mountain Biking 25 Hilltribe Trekking 25 Spas 25 EXAMPLES OF TOUR PROGRAMMES 25 FACILITIES IN MAE HONG SON 27 Accommodations 27 Restaurants 40 Travel Agents 41 USEFUL CALLS 42 61-03-110 Incover 003-046 Mae Hong Son eng i_coated.indd 5 5/4/2561 BE 21:26 Wat Chong Klang Mae Hong Son 61-03-110 Incover 003-046 Mae Hong Son eng i_coated.indd 6 5/4/2561 BE 21:26 Thai Term Glossary THAI YAI CULTURE Amphoe: District The Thai Yai can be seen along the northern Ban: Village border with Myanmar. -

1.3 Characteristics of Mae Hong Son Province

United Nations Development Programme Country: Thailand ADDENDUM TO THE ORIGINAL PROJECT DOCUMENT OF THE GEF RE MHS PROJECT Project Title: Promoting Renewable Energy in Mae Hong Son Province National Priority or Managing natural resources and environmental sustainability. UNDAF Goal: CP/UNDAF outcome Thailand is better prepared to coherently address climate change and environmental (2012-2016): security issues through the enhancement of national capacity and policy readiness. Expected Outcome Power generation capacity from renewable energies in MHS increased both for on-grid Indicators (those that will as well as off-grid applications. result from the project): Renewable energy integrated into provincial development planning. Responsible Parties: The project will be implemented under DIM (Direct Implementation Modality) in close cooperation with the MHS office of the governor and the Provincial energy Office (PEO). Implementing Partner(s): MHS Office of the Governor; Provincial Energy Office (PEO), Ministry of Energy; Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE), Ministry of Energy; Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), Ministry of Energy; Department of National Parks, Wildlife, and Plants Conservation (DNP), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Royal Forest Department (RFD), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment; Department of Public Administration MHS (DOPA); Provincial Administrative Organization (PAO); And other local government bodies. Brief Description: Despite the government’s -

A Half-Century of Photography in Northern Thailand ย" อ น ย ล ช น ช า ติ พั น ธุ

PICTURING HIGHLANDERS A half-century of photography in Northern Thailand ย" อ น ย ล ช น ช า ติ พั น ธุ. ภาพถ%ายกึ่งศตวรรษวิถีชีวิตบนพื้นที่สูงในภาคเหนือ ย"อนยลชนชาติพันธุ. PICTURING HIGHLANDERS A half-century of photography in Northern Thailand ย" อ น ย ล ช น ช า ติ พั น ธุ. ภาพถ%ายกึ่งศตวรรษวิถีชีวิตบนพื้นที่สูงในภาคเหนือ บรรณาธิการ ประสิทธิ์ ลีปรีชา และ โอลิเวียรG เอฟรารGด Pictures selected and edited by Olivier Evrard and Prasit Leepreecha 1 PICTURING HIGHLANDERS A half-century of photography in Northern Thailand ย"อนยลชนชาติพันธุ. ภาพถ%ายกึ่งศตวรรษวิถีชีวิตบนพื้นที่สูงในภาคเหนือ þşĩĝĵġĔĮăėğğĐĮĖĴĄğĝþĩăĦŷĖĭĄħĩĦĝĴđĹħŞăćĮĒİ ŶğĬĦİĔĕİńġıŶğıćĮ! ĞşĩĖĞġćĖćĮĒİĚĭĖĕĴŢĜĮĚēŞĮĞĄIJŀăĤĒģğğĥģİēıćıģİĒėĖĚijŁĖĔıŀĦĵăĻĖĜĮĀĸħĖijĩ! ĸćıĞăĻħĝŞ- ĤĵĖĞŢĤIJĄĥĮćĮĒİĚĭĖĕĴŢĹġĬĄĮğĚĭďĖĮĹġĬĦēĮėĭĖģİąĭĞĸĚijŀĩĄĮğĚĭďĖĮĝħĮģİĔĞĮġĭĞĸćıĞăĻħĝŞ%(()! $(%ħĖşĮ! $!ĜĮĚēŞĮĞ!<!ĸĩěğĮğŢđĺĩġİĸģıĞğŢĘĵşĹĒŞăğŞģĝ!<<!ħĝĮĞİŁĝĦĒĵđİĺĩĘĵşĸĹŶġ!<<!ćijŀĩĸğijŀĩă! **, <F5A,*+ ,*' )*% +#% * C\VgheXffX_XVgXWTaWXW\gXWUlB_\i\Xe8ieTeWTaWCeTf\g?XXceXXV[TėğğĐĮĕİĄĮğŶğĬĦİĔĕİńġıŶğıćĮĹġĬĺĩġİĸģıĞğŢĸĩěğĮğŢđ 6XagXeYbe8g[a\VFghW\XfTaW7XiX_bc`Xag68F7bY6[\TaZ@T\Ha\iXef\glTaW<afg\ghgWXEXV[XeV[Xcbhe_X7ÑiX_bccX`Xag ĤĵĖĞŢĤIJĄĥĮćĮĒİĚĭĖĕĴŢĹġĬĄĮğĚĭďĖĮĝħĮģİĔĞĮġĭĞĸćıĞăĻħĝŞĹġĬĦēĮėĭĖģİąĭĞĸĚijŀĩĄĮğĚĭďĖĮĹħŞăęğĭŀăĸĤĦ 9\efgchU_\f[XW%#$&Ul6XagXeYbe8g[a\VFghW\XfTaW7XiX_bc`XagTaW<afg\ghgWXEXV[XeV[Xcbhe_X7ÑiX_bccX`Xag ĚİĝĚŢĀğĭŁăĹğĄŶŖĚ!Ĥ!%(()ĺđĞĤĵĖĞŢĤIJĄĥĮćĮĒİĚĭĖĕĴŢĹġĬĄĮğĚĭďĖĮĹġĬĦēĮėĭĖģİąĭĞĸĚijŀĩĄĮğĚĭďĖĮ 8`T\_-VXfW3V`h!TV!g[[ggc-""jjj!VXfW!fbV!V`h!TV!g[[ggc-""jjj!g[T\_TaWX!\eW!Ye JTa\WTCe\ag\aZ6[\TaZ@T\G[T\_TaW$###Vbc\XfĚİĝĚŢĔıŀģĖİđĮĄĮğĚİĝĚŢąĭăħģĭđĸćıĞăĻħĝŞąŷĖģĖ$###ĸġŞĝ -

A Model in Promoting Highland Terrace Paddy Cultivation Technology in Northern Thailand

IJERD – International Journal of Environmental and Rural Development (2018) 9-1 Research article erd A Model in Promoting Highland Terrace Paddy Cultivation Technology in Northern Thailand ALISA SAHAHIRUN* Suphanburi Provincial Agricultural Extension Office, Department of Agricultural Extension, Suphanburi Province, Thailand Email: [email protected] ROWENA DT. BACONGUIS Institute for Governance and Rural Development, College of Public Affairs and Development, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Collage, Laguna, Philippines Received 29 December 2017 Accepted 12 May 2018 (*Corresponding Author) Abstract This study aimed to investigate the adoption of Highland Terrace Paddy Cultivation Technology (HTPCT) in Northern Thailand. HTPCT was promoted by the Rice Department in 2003 in four provinces of Northern Thailand under the Royal Development Project. Previous studies showed increased yields using HTPCT while cost of converting sloping lands into terrace paddy can be recouped in a few years. However, despite the promotion of the technology, adoption had not been widespread. To understand the limitations in the adoption process, quantitative and qualitative research was conducted in 5 villages of Chiang Mai and Mae Hong Son provinces located in Doi Ompai Mountain. Results show that overall the respondents had high level of adoption but for two practices, namely, soil fertilizer management and sequential cropping system and livestock production, the respondents had moderate level of adoption. Further, the two production practices were only partially practiced by the farmers. This means that even if the adopters converted their upland rice areas to terrace paddy, they still used some traditional technologies and did not follow all recommended HTPCT practices. The common problems mentioned by the respondents in practicing HTPCT were water and labor shortage, difficulty of land preparation, lack of bio-pesticides and green manure seeds, familiarity with traditional cultivation and their superstition which worked against widespread adoption. -

Yuam River from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Coordinates: 17°49!55"N 97°41!31"E Yuam River From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Yuam River (Thai: แมนยวม is a river in northwestern Thailand, part of the Salween watershed. It originates in the mountains of the Thanon Thong Chai Range, Khun Yuam District, Mae Hong Son Province, Thailand. The river flows in a north–south direction and then in Sop Moei District it bends westwards and then Yuam River (แมนยวม) northwestwards, forming a stretch of the Thai/Burmese border shortly before it joins the left bank of the Moei River, shortly before its confluence with the Salween. A major dam is projected on this river as part of a water diversion plan from the Salween to the Chao Phraya River.[1] The Ngao River, which unlike most rivers in Thailand flows northwards, is one of the Yuam's main tributaries.[2] See also River systems of Thailand Mae Ngao National Park The Yuam River near Mae Sariang References Countries Thailand, Burma 1. Salween Watch - Recent Dam and Water Diversion Plans (http://www.salweenwatch.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=51&Itemid=60) State Mae Hong Son Province (Thailand) 2. Mae Ngao National Park (http://www.chiangmai-chiangrai.com/national_parks-mae_ngao.html) Districts Khun Yuam District, Mae La Noi District, Mae Sariang District, External links Sop Moei District Nam Ngao (http://www.jpower.co.jp/english/international/consultation/detail_old/se_as_thailand05.pdf) Source Salawin National Park (http://www.4to40.com/travel/print.asp?p=Salawin_National_Park&k=Yuam_River) - location Thanon Thong Chai Range, -

Terminal Evaluation (TE) Thailand

Terminal Evaluation (TE) Thailand: Promoting Renewable Energy in Mae Hong Son Province (MHS-RE) UNDP-GEF Project December 15, 2017 GEF Project ID: 3359 UNDP PIMS: 3908 #1 MHS RE Option – a $4.50 standard cook stove (left) - and a $9 (250 Baht) Improved Cook Stove (right) that uses 30-50% less firewood and lasts twice as long as a standard cook stove 1 | P a g e #2 MHS RE Option- $90 (3000 Baht) Complete Solar Home System that is already commercially available in MHS City with 3*1W LED Lamps, 2 USB Ports, Li-Ion Battery, & credible 1-year guarantee GEF Strategic Program: Program 3: Promoting market approaches for renewable energy Program 4: Promoting sustainable energy production from biomass. Implementing Agency: UNDP Implementing Partners: Thailand Environment Institute (TEI) NGO in Phase 1 (2011 - 2013) and UNDP- Direct Implementation Modality (DIM) in Phase 2 (2014 - 2017) Evaluation Team: International Consultant: Frank Pool ([email protected]) National Consultant: Piyathip Eawpanich ([email protected]) The Terminal Evaluation was undertaken from September to December 2017 Acknowledgements The evaluation team wishes to thank UNDP and the Thailand: Promoting Renewable Energy in Mae Hong Son Province (MHS-RE) project staff in providing the necessary project background and project reporting information and documentation to underpin the evaluation. The team also thanks the relevant Thailand local government officials, stakeholders, equipment suppliers, project beneficiaries, and project partners for their helpful cooperation -

Annual Progress Report

United Nations Joint Programme on Integrated Highland Livelihood Development in Mae Hong Son ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT Reporting Period: 1 January – 31 December 2010 Prepared by The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations – Lead Organization of the UN Joint Programme in Mae Hong Son Mae Hong Son, Thailand 29 March 2011 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AOPC Association of Older People’s Clubs BPP Border Patrol Police CAF Community Activity Facilitator CBO Community‐Based Organization CBT‐I Thailand Community‐Based Tourism Institute CDC Communicable Disease Control CHC Community Health Center CHV Community Health Volunteer CHW Community Health Worker CLC Community Learning Center CMU Chiang Mai University CPD Cooperative Promotion Department CWA Common Working Area DEDE Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency DLD Department of Livestock Development DHO District Health Office EH Environmental Health ESO Education Service Area 1 or 2 Office FACE Fight Against Child Exploitation FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FoN Faculty of Nutrition FRESH Focusing Resources on Effective School Health GIS Geographic Information System HAI HelpAge International HCW Health Care Worker HIV/AIDS Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ICT Information and Communication Technologies IEC Information, Education and Communication IOM International Organization for Migration IP Implementing Partner KPI King Prajadhipok’s Institute LAO Local Administration Office LCC Livelihoods -

Shifting Cultivation, Livelihood and Food Security New and Old Challenges for Indigenous Peoples in Asia

Shifting Cultivation, Livelihood and Food Security New and Old Challenges for Indigenous Peoples in Asia Editor Christian Erni Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and International Work Group For Indigenous Affairs and Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact Bangkok, 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), or of the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) or of the Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO, or IWGIA or AIPP in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO, or IWGIA or AIPP. 978-92-5-108761-9 (FAO) © FAO, IWGIA and AIPP, 2015 FAO, IWGIA and AIPP encourage the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO, IWGIA and AIPP as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s, IWGIA’s and AIPP’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way.