Lake Missoula and Its Floods by Kendall L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open File Report

RECONNAISSANCE SURFICIAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING OF THE LATE CENOZOIC SEDIMENTS OF THE COLUMBIA BASIN, WASHINGTON by James G. Rigby and Kurt Othberg with contributions from Newell Campbell Larry Hanson Eugene Kiver Dale Stradling Gary Webster Open File Report 79-3 September 1979 State of Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Olympia, Washington CONTENTS Introduction Objectives Study Area Regional Setting 1 Mapping Procedure 4 Sample Collection 8 Description of Map Units 8 Pre-Miocene Rocks 8 Columbia River Basalt, Yakima Basalt Subgroup 9 Ellensburg Formation 9 Gravels of the Ancestral Columbia River 13 Ringold Formation 15 Thorp Gravel 17 Gravel of Terrace Remnants 19 Tieton Andesite 23 Palouse Formation and Other Loess Deposits 23 Glacial Deposits 25 Catastrophic Flood Deposits 28 Background and previous work 30 Description and interpretation of flood deposits 35 Distinctive geomorphic features 38 Terraces and other features of undetermined origin 40 Post-Pleistocene Deposits 43 Landslide Deposits 44 Alluvium 45 Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Older Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Colluvium 46 Sand Dunes 46 Mirna Mounds and Other Periglacial(?) Patterned Ground 47 Structural Geology 48 Southwest Quadrant 48 Toppenish Ridge 49 Ah tanum Ridge 52 Horse Heaven Hills 52 East Selah Fault 53 Northern Saddle Mountains and Smyrna Bench 54 Selah Butte Area 57 Miscellaneous Areas 58 Northwest Quadrant 58 Kittitas Valley 58 Beebe Terrace Disturbance 59 Winesap Lineament 60 Northeast Quadrant 60 Southeast Quadrant 61 Recommendations 62 Stratigraphy 62 Structure 63 Summary 64 References Cited 66 Appendix A - Tephrochronology and identification of collected datable materials 82 Appendix B - Description of field mapping units 88 Northeast Quadrant 89 Northwest Quadrant 90 Southwest Quadrant 91 Southeast Quadrant 92 ii ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. -

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods—Roadside Geology

u 0 by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF Natural Resources Jennifer M. Belcher - Commissioner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor FLOOD BASALTS AND GLACIER FLOODS: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor Division of Geology and Earth Resources WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Jennifer M. Belcher-Commissio11er of Public Lands Kaleeo Cottingham-Supervisor DMSION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Raymond Lasmanis-State Geologist J. Eric Schuster-Assistant State Geologist William S. Lingley, Jr.-Assistant State Geologist This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources P.O. Box 47007 Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Price $ 3.24 Tax (WA residents only) ~ Total $ 3.50 Mail orders must be prepaid: please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks payable to the Department of Natural Resources. Front Cover: Palouse Falls (56 m high) in the canyon of the Palouse River. Printed oo recycled paper Printed io the United States of America Contents 1 General geology of southeastern Washington 1 Magnetic polarity 2 Geologic time 2 Columbia River Basalt Group 2 Tectonic features 5 Quaternary sedimentation 6 Road log 7 Further reading 7 Acknowledgments 8 Part 1 - Walla Walla to Palouse Falls (69.0 miles) 21 Part 2 - Palouse Falls to Lower Monumental Dam (27.0 miles) 26 Part 3 - Lower Monumental Dam to Ice Harbor Dam (38.7 miles) 33 Part 4 - Ice Harbor Dam to Wallula Gap (26.7 mi les) 38 Part 5 - Wallula Gap to Walla Walla (42.0 miles) 44 References cited ILLUSTRATIONS I Figure 1. -

Northwest Exposure Winners Revealed!

Winter weekend getaway in Leavenworth A Publication of Washington Trails Association | wta.org Northwest Exposure Winners Revealed! 10 Trails for This Winter State Parks Centennial 2013 Volunteer Vacations Jan+Feb 2013 Jan+Feb 2013 20 16 32 NW Weekend: Leavenworth » Eli Boschetto NW Explorer An alpine holiday is waiting for you on the east side of the Cascades. Snowshoe, ski, take in the annual Ice Fest Northwest Exposure celebration or just relax away from home. » p.20 Congratulations to the winners of WTA's 2012 Northwest Exposure photo contest. Images from across the state— Tales From the Trail » Craig Romano and a calendar for planning hikes too! » center Guidebook author Craig Romano shares insights and lessons learned from years of hiking experience. » p.24 Nordic Washington » Holly Weiler Hit the tracks this winter on Nordic skis. Destinations Epic Trails » Wonderland » Tami Asars across Washington will help you find your ideal escape at Info and tips to help you plan your own hiking adventure some of the best resorts and Sno-Parks. » p.16 on the classic round-the-mountain trail. » p.32 WTA at Work 2013 marks the 100th anniversary of Trail Work » Sarah Rich Washington's state park system. With Bridge-building in the Methow » p.10 more than 700 miles of hiking trails, Engineering Trails » Janice Van Cleve make a plan to visit one this year. » p.8 Turnpikes—what they are and how they're constructed » p.12 Advocacy » Jonathan Guzzo Budget concerns for 2013 » p.14 Youth on Trails » Krista Dooley Snowshoeing with kids » p.15 Trail Mix Gear Closet » Winter camping essentials » p.22 Nature Nook » Tami Asars Birds, beasts and blooms in the NW » p.25 Cape Disappointment, by Jeremy Horton 2 Washington Trails | Jan+Feb 2013 | wta.org Guest Contributors TAMI ASARS is a writer, photographer and career hiker. -

RCFB April 2021 Page 1 Agenda TUESDAY, April 27 OPENING and MANAGEMENT REPORTS 9:00 A.M

REVISED 4/8/21 Proposed Agenda Recreation and Conservation Funding Board April 27, 2021 Online Meeting ATTENTION: Protecting the public, our partners, and our staff are of the utmost importance. Due to health concerns with the novel coronavirus this meeting will be held online. The public is encouraged to participate online and will be given opportunities to comment, as noted below. If you wish to participate online, please click the link below to register and follow the instructions in advance of the meeting. Technical support for the meeting will be provided by RCO’s board liaison who can be reached at [email protected]. Registration Link: https://zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_JqkQAGCrRSOwbHLmg3a6oA Phone Option: (669)900-6833 - Webinar ID: 967 5491 2108 Location: RCO will also have a public meeting location for members of the public to listen via phone as required by the Open Public Meeting Act, unless this requirement is waived by gubernatorial executive order. In order to enter the building, the public must not exhibit symptoms of the COVID-19 and will be required to comply with current state law around personal protective equipment. RCO staff will meet the public in front of the main entrance to the natural resources building and escort them in. *Additionally, RCO will record this meeting and would be happy to assist you after the meeting to gain access to the information. Order of Presentation: In general, each agenda item will include a short staff presentation and followed by board discussion. The board only makes decisions following the public comment portion of the agenda decision item. -

The Missoula Flood

THE MISSOULA FLOOD Dry Falls in Grand Coulee, Washington, was the largest waterfall in the world during the Missoula Flood. Height of falls is 385 ft [117 m]. Flood waters were actually about 260 ft deep [80 m] above the top of the falls, so a more appropriate name might be Dry Cataract. KEENAN LEE DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND GEOLOGICAL ENGINEERING COLORADO SCHOOL OF MINES GOLDEN COLORADO 80401 2009 The Missoula Flood 2 CONTENTS Page OVERVIEW 2 THE GLACIAL DAM 3 LAKE MISSOULA 5 THE DAM FAILURE 6 THE MISSOULA FLOOD ABOVE THE ICE DAM 6 Catastrophic Flood Features in Eddy Narrows 6 Catastrophic Flood Features in Perma Narrows 7 Catastrophic Flood Features at Camas Prairie 9 THE MISSOULA FLOOD BELOW THE ICE DAM 13 Rathdrum Prairie and Spokane 13 Cheny – Palouse Scablands 14 Grand Coulee 15 Wallula Gap and Columbia River Gorge 15 Portland to the Pacific Ocean 16 MULTIPLE MISSOULA FLOODS 17 AGE OF MISSOULA FLOODS 18 SOME REFERENCES 19 OVERVIEW About 15 000 years ago in latest Pleistocene time, glaciers from the Cordilleran ice sheet in Canada advanced southward and dammed two rivers, the Columbia River and one of its major tributaries, the Clark Fork River [Fig. 1]. One lobe of the ice sheet dammed the Columbia River, creating Lake Columbia and diverting the Columbia River into the Grand Coulee. Another lobe of the ice sheet advanced southward down the Purcell Trench to the present Lake Pend Oreille in Idaho and dammed the Clark Fork River. This created an enormous Lake Missoula, with a volume of water greater than that of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined [530 mi3 or 2200 km3]. -

A Model for Measuring the Benefits of State Parks for the Washington State Parks And

6 A Model for Measuring the Benefits of State Parks for the Washington State Parks and january 201 january Recreation Commission Prepared By: Prepared For: Earth Economics Washington State Parks and Tacoma, Washington Recreation Commission Olympia, Washington Primary Authors: Tania Briceno, PhD, Ecological Economist, Earth Economics Johnny Mojica, Research Analyst, Earth Economics Suggested Citation: Briceno, T., Mojica, J. 2016. Statewide Land Acquisition and New Park Development Strategy. Earth Economics, Tacoma, WA. Acknowledgements: Thanks to all who supported this project including the Earth Economics team: Greg Schundler (GIS analysis), Corrine Armistead (Research, Analysis, and GIS), Jessica Hanson (editor), Josh Reyneveld (managing director), Sage McElroy (design); the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission: Tom Oliva, Katie Manning, Steve Hahn, Steve Brand, Nikki Fields, Peter Herzog and others. We would also like to thank our Board of Directors for their continued guidance and support: Ingrid Rasch, David Cosman, Sherry Richardson, David Batker, and Joshua Farley. The authors are responsible for the content of this report. Cover image: Washington State Department of Transportation ©2016 by Earth Economics. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Executive Summary Washington’s state parks provide a myriad of benefits to both urban and rural environments and nearby residents. Green spaces within state parks provide direct benefits to the populations living in close proximity. For example, the forests within state parks provide outdoor recreational opportunities, and they also help to store water and control flooding during heavy rainfalls, improve air quality, and regulate the local climate. -

This File Was Created by Scanning the Printed Publication

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Editors SHARON E. CLARKE is a geographer and GIS analyst, Department of Forest Science, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331; and SANDRA A. BRYCE is a biogeographer, Dynamac Corporation, Environmental Protection Agency, National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, Western Ecology Division, Corvallis, OR 97333. This document is a product of cooperative research between the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; the Forest Science De- partment, Oregon State University; and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Cover Artwork Cover artwork was designed and produced by John Ivie. Abstract Clarke, Sharon E.; Bryce, Sandra A., eds. 1997. Hierarchical subdivisions of the Columbia Plateau and Blue Mountains ecoregions, Oregon and Washington. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-395. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 114 p. This document presents two spatial scales of a hierarchical, ecoregional framework and provides a connection to both larger and smaller scale ecological classifications. The two spatial scales are subregions (1:250,000) and landscape-level ecoregions (1:100,000), or Level IV and Level V ecoregions. Level IV ecoregions were developed by the Environmental Protection Agency because the resolution of national-scale ecoregions provided insufficient detail to meet the needs of state agencies for estab- lishing biocriteria, reference sites, and attainability goals for water-quality regulation. For this project, two ecoregions—the Columbia Plateau and the Blue Mountains— were subdivided into more detailed Level IV ecoregions. -

PALOUSE to PINES LOOP

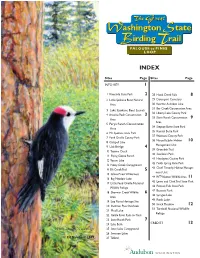

PA LOUSE to PINE S LOOP INDEX Sites Page Sites Page INFO KEY 1 1 Riverside State Park 2 28 Hawk Creek Falls 8 2 Little Spokane River Natural 29 Davenport Cemetery Area 30 Reardan Audubon Lake 31 Iller Creek Conservation Area 3 Lake Spokane Boat Launch 32 Liberty Lake County Park 4 Antoine Peak Conservation 3 33 Slavin Ranch Conservation Area 9 Area 5 Feryn Ranch Conservation 34 Steptoe Butte State Park Area 35 Kamiak Butte Park 6 Mt. Spokane State Park 37 Wawawai County Park 7 Pend Oreille County Park 38 Nisqually John Habitat 8 Calispell Lake 10 Management Unit 9 Usk Bridge 4 39 Greenbelt Trail 10 Tacoma Creek 40 Swallow’s Park 11 Flying Goose Ranch 41 Headgates County Park 12 Yocum Lake 42 Fields Spring State Park 13 Noisy Creek Campground 43 Chief Timothy Habitat Manage- 14 Elk Creek Trail 5 ment Unit 15 Salmo Priest Wilderness 44 WT Wooten Wildlife Area 16 Big Meadow Lake 11 45 Lewis and Clark Trail State Park 17 Little Pend Oreille National 46 Palouse Falls State Park Wildlife Refuge 47 Bassett Park 18 Sherman Creek Wildlife 6 48 Sprague Lake Area 49 Rock Lake 19 Log Flume Heritage Site 50 Smick Meadow 20 Sherman Pass Overlook 12 51 Turnbull National Wildlife 21 Mud Lake Refuge 22 Kettle River Rails-to-Trails 23 Lone Ranch Park 7 24 Lake Beth CREDITS 13 White-headed Woodpecker 25 Swan Lake Campground 26 Swanson Lakes © Ed Newbold, 2009 27 Telford The Great Washington State Birding Trail 1 PALOUSE to PINES LOOP INFO KEY Map ICons Best seasons for birding (spring, summer, fall, winter) Developed camping available, including restrooms; fee required Restroom available at day-use site Handicapped restroom and handicapped trail or viewing access Site located in an Important Bird Area Fee required; passes best obtained prior to travel. -

Field-Trip Guide to the Vents, Dikes, Stratigraphy, and Structure of the Columbia River Basalt Group, Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington

Field-Trip Guide to the Vents, Dikes, Stratigraphy, and Structure of the Columbia River Basalt Group, Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5022–N U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Palouse Falls, Washington. The Palouse River originates in Idaho and flows westward before it enters the Snake River near Lyons Ferry, Washington. About 10 kilometers north of this confluence, the river has eroded through the Wanapum Basalt and upper portion of the Grande Ronde Basalt to produce Palouse Falls, where the river drops 60 meters (198 feet) into the plunge pool below. The river’s course was created during the cataclysmic Missoula floods of the Pleistocene as ice dams along the Clark Fork River in Idaho periodically broke and reformed. These events released water from Glacial Lake Missoula, with the resulting floods into Washington creating the Channeled Scablands and Glacial Lake Lewis. Palouse Falls was created by headward erosion of these floodwaters as they spilled over the basalt into the Snake River. After the last of the floodwaters receded, the Palouse River began to follow the scabland channel it resides in today. Photograph by Stephen P. Reidel. Field-Trip Guide to the Vents, Dikes, Stratigraphy, and Structure of the Columbia River Basalt Group, Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington By Victor E. Camp, Stephen P. Reidel, Martin E. Ross, Richard J. Brown, and Stephen Self Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5022–N U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. -

Iron Horse State Park Trail – Renaming Effort/Trail Update – Report

Don Hoch Direc tor STATE O F WASHINGTON WASHINGTON STATE PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSI ON 1111 Israel Ro ad S.W. P.O . Box 42650 Olympia, WA 98504-2650 (360) 902-8500 TDD Telecommunications De vice for the De af: 800-833 -6388 www.parks.s tate.wa.us March 22, 2018 Item E-5: Iron Horse State Park Trail – Renaming Effort/Trail Update – Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: This item reports to the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission the current status of the process to rename the Iron Horse State Park Trail (which includes the John Wayne Pioneer Trail) and a verbal update on recent trail management activities. This item advances the Commission’s strategic goal: “Provide recreation, cultural, and interpretive opportunities people will want.” SIGNIFICANT BACKGROUND INFORMATION: Initial acquisition of Iron Horse State Park Trail by the State of Washington occurred in 1981. While supported by many, the sale of the former rail line was controversial for adjacent property owners, some of whom felt that the rail line should have reverted back to adjacent land owners. This concern, first expressed at initial purchase of the trail, continues to influence trail operation today. The trail is located south of, and runs roughly parallel to I-90 (see Appendix 1). The 285-mile linear property extends from North Bend, at its western terminus, to the Town of Tekoa, on the Washington-Idaho border to the east. The property consists of former railroad corridor, the width of which varies between 100 feet and 300 feet. The trail tread itself is typically 8 to 12 feet wide and has been developed on the rail bed, trestles, and tunnels of the old Chicago Milwaukee & St. -

Columbia Plateau Trail Management Plan

COLUMBIA PLATEAU TRAIL STATE PARK MANAGEMENT PLAN June 5, 2006 Washington State Parks Mission The Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission acquires, operates, enhances, and protects a diverse system of recreational, cultural, and natural sites. The Commission fosters outdoor recreation and education statewide to provide enjoyment and enrichment for all and a valued legacy to future generations. Columbia Plateau Trail State Park Management Plan Page 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND CONTACTS The Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission gratefully acknowledges the many stakeholders and the staff of Columbia Plateau Trail State Park who participated in public meetings, reviewed voluminous materials, and made this a better plan because of if. Plan Author Bruce Beyerl, Environmental Planner, Eastern Region Columbia Plateau Trail State Park Area Management Planning Team Daniel Farber, CAMP Project co-lead Peter Herzog, CAMP Project co-lead Mark Truitt, Columbia Plateau Trail State Park Manager Bill Byrne, Columbia Plateau Trail State Park Manager, Retired Jim Harris, Eastern Region Manager Tom Ernsberger, Eastern Region Assistant Manager – Resource Stewardship Bill Fraser, Parks Planner Washington State Park and Recreation Commission 7150 Cleanwater Lane, P.O. Box 42650 Olympia WA 98504-2650 Tel: (360) 902-8500 Fax: (360) 753-1591 TDD: (360) 664-3133 Commissioners (at time of land classification adoption): Clyde Anderson Mickey Fearn Bob Petersen Eliot Scull Joe Taller Joan Thomas Cecilia Vogt Rex Derr, Director Columbia Plateau Trail State Park Management Plan Page 2 COLUMBIA PLATEAU TRAIL STATE PARK LAND CLASSES, RESOURCE ISSUES AND MANAGEMENT APPROACHES CERTIFICATE OF ADOPTION The signatures below certify the adoption of this document by Washington State Parks for the continued management of Columbia Plateau Trail State Park. -

Fidalgo Bay Resort Anacortes, WA

Fidalgo Bay Resort Anacortes, WA Fidalgo Bay Resort is located on Fidalgo Island and is your "home port" for all the San Juan Islands. A place to relax and enjoy the beauty of the Northwest. Site Information Special Attractions Directions 148 sites. Full hookup sites. Anacortes Take Exit #230. Go West on Pull thru sites. 20/30/50 AMP Mt. Baker Hwy20 for 13 miles. Stay in the service San Juan Islands right lane. Turn right onto Victoria, BC Fidalgo Bay Road. Travel along Can accommodate RVs up to 45’ Mount Vernon the bay for 1 mile. We are on the Seattle right. Amenities/Facilities Wi-Fi, cable TV, comfort station, Recreation clean restrooms, showers, Over 1 mile of beach, walking & laundry, handicap accessible, swimming at Whistle Lake gift shop, clubhouse, fitness room, park model cabins, friendly & knowledgeable staff Of Interest Rates $33-$60 The City of Anacortes has world famous parks, forestlands and is great for hiking, biking, and all types of recreation. Contact Information 4701 Fidalgo Bay Road Anacortes, WA 98221 800.727.5478 [email protected] www.fidalgobay.com Beach RV Park Benton City, WA Beach RV is an Oasis of beautiful riverfront scenery tucked into the exciting heart of Eastern Washington's wine country. The Beautiful Yakima River borders the South side of the park and although it is not a "beach", it is a lovely setting. Site Information Special Attractions Directions 100 sites. Full hookup sites. Water Parks Take exit 96 off of I82. Travel Pull thru sites. Back in sites. River Tours north on Highway 225.