Neural Social Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Universe, Life and Everything…

Our current understanding of our world is nearly 350 years old. Durston It stems from the ideas of Descartes and Newton and has brought us many great things, including modern science and & increases in wealth, health and everyday living standards. Baggerman Furthermore, it is so engrained in our daily lives that we have forgotten it is a paradigm, not fact. However, there are some problems with it: first, there is no satisfactory explanation for why we have consciousness and experience meaning in our The lives. Second, modern-day physics tells us that observations Universe, depend on characteristics of the observer at the large, cosmic Dialogues on and small, subatomic scales. Third, the ongoing humanitarian and environmental crises show us that our world is vastly The interconnected. Our understanding of reality is expanding to Universe, incorporate these issues. In The Universe, Life and Everything... our Changing Dialogues on our Changing Understanding of Reality, some of the scholars at the forefront of this change discuss the direction it is taking and its urgency. Life Understanding Life and and Sarah Durston is Professor of Developmental Disorders of the Brain at the University Medical Centre Utrecht, and was at the Everything of Reality Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in 2016/2017. Ton Baggerman is an economic psychologist and psychotherapist in Tilburg. Everything ISBN978-94-629-8740-1 AUP.nl 9789462 987401 Sarah Durston and Ton Baggerman The Universe, Life and Everything… The Universe, Life and Everything… Dialogues on our Changing Understanding of Reality Sarah Durston and Ton Baggerman AUP Contact information for authors Sarah Durston: [email protected] Ton Baggerman: [email protected] Cover design: Suzan Beijer grafisch ontwerp, Amersfoort Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. -

Strategies for Social Skills for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder

National Association of Special Education Teachers AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER SERIES Strategies for Social Skills for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder Introduction One of the most important areas for intervention for children with autism will be in the area of social skills development. Most students with ASD would like to be part of the social world around them. They have a need to interact socially and be involved with others. However, one of the defining characteristics of ASD is impairment in social interactions and social skills. Students with ASD have not automatically learned the rules of interaction with others, and they are unable to follow these unwritten rules of social behavior. This article will focus on this very important and relevant issue. Most students with ASD would like to be part of the social world around them. They have a need to interact socially and be involved with others. However, one of the defining characteristics of ASD is impairment in social interactions and social skills. Students with ASD have not automatically learned the rules of interaction with others, and they are unable to follow these unwritten rules of social behavior. Many people with ASD are operating on false perceptions that are rigid or overly literal. Recognizing these false perceptions can be very helpful in understanding the behavior and needs of these students in social situations. The misperceptions include: • rules apply in only a single situation • everything someone says must be true • when you do not know what to do, do nothing. Imagine how overly literal misconceptions could seriously limit social interaction. -

The Emotional and Social Intelligences of Effective Leadership

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0268-3946.htm The intelligences The emotional and social of effective intelligences of effective leadership leadership An emotional and social skill approach 169 Ronald E. Riggio and Rebecca J. Reichard Kravis Leadership Institute, Claremont McKenna College, Claremont, California, USA Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to describe a framework for conceptualizing the role of emotional and social skills in effective leadership and management and provides preliminary suggestions for research and for the development of leader emotional and social skills. Design/methodology/approach – The paper generalizes a dyadic communications framework in order to describe the process of emotional and social exchanges between leaders and their followers. Findings – The paper shows how emotional skills and complementary social skills are essential for effective leadership through a literature review and discussion of ongoing research and a research agenda. Practical implications – Suggestions for the measurement and development of emotional and social skills for leaders and managers are offered. Originality/value – The work provides a framework for emotional and social skills in order to illustrate their role in leadership and their relationship to emotional and social intelligences. It outlines a research agenda and advances thinking of the role of developable emotional and social skills for managers. Keywords Emotional intelligence, Social skills, Leadership development Paper type Conceptual paper In his classic work on managerial skills, Mintzberg (1973) listed specific interpersonal skills (i.e. the ability to establish and maintain social networks; the ability to deal with subordinates; the ability to empathize with top-level leaders) as critical for managerial effectiveness. -

Metaphors in Cognitive and Neurosciences Which Impact Have

Metaphors in Cognitive and Neurosciences Which impact have metaphors on scientific theories and models? Juliana Goschler, Darmstadt ([email protected]) Abstract In this article, I am going to explain how the most frequent metaphor types used in cognitive and neurosciences – reification and spatial metaphors, personification, and technological metaphors – are connected to theoretical problems that occur in these scientific disciplines. These theoretical problems include the idea of memory as space, which is connected with the difficulty of a realistic description of the mental lexicon, the problem of free will, and the mind-body problem. Because of some obvious parallels between metaphorical language and arguments made in the scientific description of the mind, I will argue that certain metaphors used in scientific language are not merely linguistic problems but deeply rooted in scientific arguments. This holds for metaphors that scientists are aware of as well as for unconsciously used metaphors. My observations are intended to highlight some characteristics of meta- phors in science. Furthermore, they provide a possible approach to investigating the connec- tion between linguistic and conceptual metaphors in complex cases as scientific models. Ich werde in diesem Artikel beschreiben, wie die häufigsten Metapherntypen in den Kognitions- und Neurowissenschaften – Reifikation und Raummetaphern, Personifizierung und Technikmetaphern – mit theoretischen Problemen dieser Disziplinen verknüpft sind. Diese theoretischen Probleme -

Representation and Metaphysics Proper

Richard B. Wells ©2006 CHAPTER 4 First Epilegomenon: Representation and Metaphysics Proper The pursuit of wisdom has had a two-fold origin. Diogenes Laertius § 1. Questions Raised by Representation The outline of representation presented in Chapter 3 leaves us with a number of questions we need to address. In this chapter we will take a look back at our ideas of representation and work toward the resolution of those issues that present themselves in consequence of the theory as it stands so far. I call this look back an epilegomenon, from epi – which means “over” or “upon” – and legein – “to speak.” I employ this new term because the English language seems to have no word that adequately expresses the task at hand. “Epilogue” would imply logical conclusion, while “summary” or “epitome” would suggest a simple re-hashing of what has already been said. Our present task is more than this; we must bring out the implications of representation, Critically examine the gaps in the representation model, and attempt to unite its aggregate pieces as a system. In doing so, our aim is to push farther toward “that which is clearer by nature” although we should not expect to arrive at this destination all in one lunge. Let this be my apology for this minor act of linguistic tampering.1 In particular, Chapter 3 saw the introduction of three classes of ideas that are addressed by the division of nous in its role as the agent of construction for representations. We described these ideas as ideas of the act of representing. -

The Art and Science of Framing an Issue

MAPThe Art and Science of Framing an Issue Authors Contributing Editors © January 2008, Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) and the Movement Advancement Project (MAP). All rights reserved. “Ideas are a medium of exchange and a mode of influence even more powerful than money, votes and guns. … Ideas are at the center of all political conflict.” —Deborah Stone, Policy Process Scholar, 2002 The Art and Science of 1 Framing an Issue an Issue and Science of Framing Art The The Battle Over Ideas 2 Understanding How People Think 2 What Is Framing? 4 Levels of Framing 5 Tying to Values 6 Why Should I Spend Resources on Framing? 6 How Do I Frame My Issue? 7 Step 1. Understand the Mindset of Your Target Audience 7 Step 2. Know When Your Current Frames Aren’t Working 7 Step 3. Know the Elements of a Frame 7 Step 4. Speak to People’s Core Values 9 Step 5. Avoid Using Opponents’ Frames, Even to Dispute Them 9 Step 6. Keep Your Tone Reasonable 10 Step 7. Avoid Partisan Cues 10 Step 8. Build a New Frame 10 Step 9. Stick With Your Message 11 “Ideas are a medium of exchange and a mode of influence even more powerful than money, votes and guns. … Ideas are at the center of all political conflict.” —Deborah Stone, Policy Process Scholar, 2002 2 The Battle Over Ideas Are we exploring for oil that’s desperately needed to drive our economy and sustain our nation? Or are we Think back to when you were 10 years old, staring at destroying delicate ecological systems and natural your dinner plate, empty except for a pile of soggy– lands that are a legacy to our grandchildren? These looking green vegetables. -

Reflections on the Use of Conceptual Metaphor Theory in Premodern Chinese Texts

Dao (2019) 18:323–345 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11712-019-09669-0 Metaphors of Metaphors: Reflections on the Use of Conceptual Metaphor Theory in Premodern Chinese Texts Stefano Gandolfo1 Published online: 16 July 2019 # The Author(s) 2019 Abstract In this essay, I challenge the use of Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) in the premodern Chinese setting. The dominant, implicit assumption in the literature is that conclusions reached by CMT on the ways in which cognition operates can be applied in toto and without qualification onto the makers of classical Chinese texts. I want to challenge this assumption and argue that textual evidence from premodern Chinese points to a different cognitive process. Differences in the use and conceptualization of image-based thinking as well as differences in the understanding of the relationship between words, images, and the world reveal a different cognitive process. However, I do not wish to argue for a total abandonment of the insights of CMT. Rather, I call for the need to properly qualify its findings in light of premodern Chinese use and conceptions of image-based language. Keywords Conceptual metaphor. Image-based language . Classical Chinese 1 Introduction Virtually all literature that applies Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) on premodern Chinese texts does so uncritically. The dominant, implicit assumption is that the conclusions reached by CMT on the ways in which cognition operates can be applied in toto and without qualification onto the makers of classical Chinese texts. I want to challenge this assumption and argue that textual evidence from premodern Chinese points to a different cognitive process. -

Models and Metaphors: Art and Science Álvaro Balsas; Yolanda Espiña (Eds.)

Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia ISSN 0870-5283; 2183-461X Provided for non-commercial research and education use. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. Metaphor in Analytic Philosophy and Cognitive Science Mácha, Jakub Pages 2247-2286 ARTICLE DOI https://doi.org/10.17990/RPF/2019_75_4_2247 Modelos e Metáforas: Arte e Ciência Models and Metaphors: Art and Science Álvaro Balsas; Yolanda Espiña (Eds.) 75, Issue 4, 2019 ISSUE DOI 10.17990/RPF/2019_75_4_0000 Your article is protected by copyright © and all rights are held exclusively by Aletheia – Associação Científica e Cultural. This e-offprint is furnished for personal use only (for non-commercial research and education use) and shall not be self-archived in electronic repositories. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. If you wish to self-archive your article, contact us to require the written permission of the RPF's editor. For the use of any article or a part of it, the norms stipulated by the copyright law in vigour are applicable. Authors requiring further information regarding Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.rpf.pt © 2019 by Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia | © 2019 by Aletheia – Associação Científica e Cultural Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Sociais de Braga, Praça da Faculdade, N.º 1, 4710-297 Braga (Portugal). Phone +351 253 208 080. www.rpf.pt | [email protected] Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia, 2019, Vol. 75 (4): 2247-2286. © 2019 by Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia. -

Lakoff's Theory of Moral Reasoning in Presidential Campaign

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Communication Studies Communication Studies, Department of 11-2013 Lakoff’s Theory of Moral Reasoning in Presidential Campaign Advertisements, 1952–2012 Damien S. Pfister University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Jessy J. Ohl University of Mary Washington, [email protected] Marty Nader Nebraska Wesleyan University, [email protected] Dana Griffin Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Pfister, Damien S.; Ohl, Jessy J.; Nader, Marty; and Griffin,a D na, "Lakoff’s Theory of Moral Reasoning in Presidential Campaign Advertisements, 1952–2012" (2013). Papers in Communication Studies. 53. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers/53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Communication Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Communication Studies 64:5 (November-December 2013; Special Issue: Consistency and Change in Political Campaign Communication: Ana- lyzing the 2012 Elections), pages 488-507; doi: 10.1080/10510974.2013.832340 Copyright © 2013 Central States Communication Association; published by Tay- digitalcommons.unl.edu lor & Francis Group. Used by permission. Published online October 18, 2013. Lakoff’s Theory of Moral Reasoning in Presidential Campaign Advertisements, 1952–2012 Jessy J. Ohl,1 Damien S. Pfister,1 Martin Nader,2 and Dana Griffin 1 Department of Communication Studies, University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2 Department of Political Science, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Corresponding author — Jessy J. -

Toward an Integrative Understanding of Social Behavior: New Models and New Opportunities

REVIEW ARTICLE published: 28 June 2010 BEHAVIORAL NEUROSCIENCE doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2010.00034 Toward an integrative understanding of social behavior: new models and new opportunities Daniel T. Blumstein1*, Luis A. Ebensperger 2, Loren D. Hayes 3*, Rodrigo A. Vásquez 4, Todd H. Ahern 5, Joseph Robert Burger 3†, Adam G. Dolezal 6, Andy Dosmann7, Gabriela González-Mariscal 8, Breanna N. Harris 9, Emilio A. Herrera10, Eileen A. Lacey11, Jill Mateo 7, Lisa A. McGraw12, Daniel Olazábal 13, Marilyn Ramenofsky14, Dustin R. Rubenstein15, Samuel A. Sakhai16, Wendy Saltzman 9, Cristina Sainz-Borgo10, Mauricio Soto-Gamboa17, Monica L. Stewart 3, Tina W. Wey1, John C. Wingfield14 and Larry J. Young5 1 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2 CASEB and Departamento de Ecología, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, P. Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile 3 Department of Biology, University of Louisiana at Monroe, Monroe, LA, USA 4 Institute of Ecology and Biodiversity, Departamento de Ciencias Ecologicas, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile 5 Department of Psychiatry, Center for Behavioral Neuroscience, Yerkes National Primate Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA 6 School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA 7 Committee on Evolutionary Biology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA 8 Centro de Investigacion en Reproduccion Animal, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Universidad -

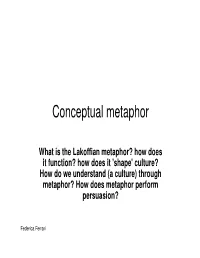

Conceptual Metaphor

Conceptual metaphor What is the Lakoffian metaphor? how does it function? how does it 'shape' culture? How do we understand (a culture) through metaphor? How does metaphor perform persuasion? Federica Ferrari NB on reference texts and didactic materials • Johnson, M. & G, Lakoff (2003). Metaphors we live by . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Pp. 1-34, p. 157) • Lakoff, G. (1993). “The contemporary theory of metaphor”. In Ortony, A. ed. (1993). Metaphor and Thought (2nd edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 202-251. • The majority of quotes are taken from the second text; inverted commas are used for “fundamental definitions”, other concepts are referred to without inverted commas, a version of the second text is also available on-line Intro • literal vs. metaphorical meaning - examples (discuss) • The balloon went up • The cat is on the map • Our relationship has hit a dead end street toward a definition of lakoffian metaphor • “The essence of metaphor is understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another”. (Lakoff G. & M. Johnson, 2003 [1980] Metaphors we live by . p. 5) • this definition in a certain way subsumes the potential development of lakoffian theory. This thanks to the conceptual domains that the choice terms “understanding” and “experiencing” evoke: (understanding and experiencing : reasoning and acting, thought and action, mind and body….) • according to Lakoff metaphor assumes a broader sense than the strictly literary one. In fact in his perspective it wouldn’t simply be a mere characteristic of language but the very vehicle for everyday reasoning and action. In this sense: • “Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature”. -

Advances in Theoretical & Computational Physics

ISSN: 2639-0108 Research Article Advances in Theoretical & Computational Physics Supreme Theory of Everything Ulaanbaatar Tarzad *Corresponding author Ulaanbaatar Tarzad, Department of Physics, School of Applied Sciences, Department of Physics, School of Applied Sciences, Mongolian Mongolian University of Science and Technology, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, University of Science and Technology E-mail: [email protected] Submitted: 27 Mar 2019; Accepted: 24 Apr 2019; Published: 06 June 2019 Abstract Not only universe, but everything has general characters as eternal, infinite, cyclic and wave-particle duality. Everything from elementary particles to celestial bodies, from electromagnetic wave to gravity is in eternal motions, which dissects only to circle. Since everything is described only by trigonometry. Without trigonometry and mathematical circle, the science cannot indicate all the beauty of harmonic universe. Other method may be very good, but it is not perfect. Some part is very nice, another part is problematic. General Theory of Relativity holds that gravity is geometric. Quantum Mechanics describes all particles by wave function of trigonometry. In this paper using trigonometry, particularly mathematics circle, a possible version of the unification of partial theories, evolution history and structure of expanding universe, and the parallel universes are shown. Keywords: HRD, Trigonometry, Projection of Circle, Singularity, The reality of universe describes by geometry, because of that not Celestial Body, Black Hole and Parallel Universes. only gravity is geometrical, but everything is it and nothing is linear. One of the important branches of geometry is trigonometry dealing Introduction with circle and triangle. For this reason, it is easier to describe nature Today scientists describe the universe in terms of two basic partial of universe by mathematics circle.