Fan Distribution, Copyright, and the Explosive Growth of Japanese Animation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8. Putting Artists and Guardians of Indigenous Works First

8 Putting Artists and Guardians of Indigenous Works First: Towards a Restricted Scope of Freedom of Panorama in the Asian Pacific Region Jonathan Barrett1 1 Introduction ‘Freedom of panorama’2 permits use of certain copyright-protected works on public display; for example, anyone may publish and sell postcards of a public sculpture.3 The British heritage version of freedom of panorama, which is followed by many jurisdictions in the Asian Pacific region,4 applies 1 Copyright © 2018 Jonathan Barrett. Senior Lecturer, School of Accounting and Commercial Law, Victoria University of Wellington. 2 The term ‘freedom of panorama’ recently came into common usage in English. It appears to be derived from the Swiss German ‘Panoramafreiheit’, which itself has only been used since the 1990s, despite the exemption existing in German law for 170 years. See Mélanie Dulong de Rosnay and Pierre-Carl Langlais ‘Public artworks and the freedom of panorama controversy: a case of Wikimedia influence’ (2017) 6(1) Internet Policy Review. 3 Incidental copying of copyright works is not considered to be a feature of freedom of panorama. See Copyright Act 1994 (NZ), s 41. 4 Asian Pacific countries are those west of the International Date Line (IDL), as defined for the purposes of the Asian Pacific Copyright Association (APCA) in Brian Fitzgerald and Benedict Atkinson (eds) Copyright Future Copyright Freedom: Marking the 40 Year Anniversary of the Commencement of Australia’s Copyright Act 1968 (Sydney University Press, Sydney, 2011) at 236. 229 MAkING COPyRIGHT WORk FOR THE ASIAN PACIFIC? to buildings, sculptures and works of artistic craftsmanship on permanent display in a public place or premises open to the public.5 These objects may be copied in two dimensions, such as photographs. -

Orphan Works and Mass Digitization Report

united states copyright office Orphan Works and Mass Digitization a report of the register of copyrights june 2015 united states copyright office Orphan Works and Mass Digitization a report of the register of copyrights june 2015 U.S. Copyright Office Orphan Works and Mass Digitization ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This Report reflects the dedication and expertise of the Office of Policy and International Affairs at the U.S. Copyright Office. Karyn Temple Claggett, Associate Register of Copyrights and Director of Policy and International Affairs, managed the overall study process, including coordination of the public comments and roundtable hearings, analysis, drafting, and recommendations. I am also extremely grateful to Senior Counsel Kevin Amer and Attorney- Advisor Chris Weston (Office of the General Counsel), who served as the principal authors of the Report and made numerous important contributions throughout the study process. Senior Advisor to the Register Catie Rowland and Attorney-Advisor Frank Muller played a significant role during the early stages of the study, providing research, drafting, and coordination of the public roundtable discussions. In addition, Ms. Rowland and Maria Strong, Deputy Director of Policy and International Affairs, reviewed a draft of the Report and provided important insights. Barbara A. Ringer Fellows Michelle Choe and Donald Stevens provided helpful research and analysis for several sections of the Report. Senior Counsel Kimberley Isbell, Counsels Brad Greenberg and Aurelia Schultz, Attorney-Advisors Katie Alvarez and Aaron Watson, and Law Clerk Konstantia Katsouli contributed valuable research and citation assistance. Finally, I would like to thank the many interested parties who participated in the public roundtables and submitted written comments to the Office. -

Meta-Con-2014-FINAL.Pdf

Convention Operations and Answers General Rules Weapon and Large Prop Rules Our convention has a number of rules, policies, and regulations All weapons and large props must be inspected and approved by our that help make the convention run smoothly and be as fun as operations or security staff at the convention. We will then “peace mark” possible for everyone. We encourage you to read our rules to un- them, by affixing a ribbon or mark that indicates we have checked them, and, if necessary “peace bond” them by using ribbon or ties to keep derstand what is expected to help make the best, most success- your weapon from being drawn or used (for example, by someone who ful, and most fun weekend possible. In addition to these general doesn’t know the rules and sneaks up behind you and grabs it). Attend- conduct policies, we also have rules and guidelines for cosplay, ees must realize that it is a privilege to bring large props and weapons press, exhibitors, and others. Violations of these rules and respon- to the convention, and everyone must take great care to be careful not sibilities can result in loss of privileges, up to and including ejec- to damage things, whack people, or otherwise do anything that seems tion without refund, legal action, or involvement of the authorities. dangerous. We allow certain specific prop weapons and large prop items, but anything not listed below is not allowed. Please understand that due Rule Number One: Do not do anything that could make the to crowding, space, or safety issues, we may have to change the rules mid-convention at any time. -

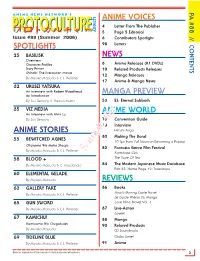

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Piracy Or Productivity: Unlawful Practices in Anime Fansubbing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Publication Archive Aalto-yliopisto Teknillinen korkeakoulu Informaatio- ja luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietotekniikan tutkinto-/koulutusohjelma Teemu Mäntylä Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Diplomityö Espoo 3. kesäkuuta 2010 Valvoja: Professori Tapio Takala Ohjaaja: - 2 Abstract Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Over a short period of time, Japanese animation or anime has grown explosively in popularity worldwide. In the United States this growth has been based on copyright infringement, where fans have subtitled anime series and released them as fansubs. In the absence of official releases fansubs have created the current popularity of anime, which companies can now benefit from. From the beginning the companies have tolerated and even encouraged the fan activity, partly because the fans have followed their own rules, intended to stop the distribution of fansubs after official licensing. The work explores the history and current situation of fansubs, and seeks to explain how these practices adopted by fans have arisen, why both fans and companies accept them and act according to them, and whether the situation is sustainable. Keywords: Japanese animation, anime, fansub, copyright, piracy Tiivistelmä Piratismia vai tuottavuutta: laittomat toimintatavat animen fanikäännöksissä Japanilaisen animaation eli animen suosio maailmalla on lyhyessä ajassa kasvanut räjähdysmäisesti. Tämä kasvu on Yhdysvalloissa perustunut tekijänoikeuksien rikkomiseen, missä fanit ovat tekstittäneet animesarjoja itse ja julkaisseet ne fanikäännöksinä. Virallisten julkaisujen puutteessa fanikäännökset ovat luoneet animen nykyisen suosion, jota yhtiöt voivat nyt hyödyntää. Yhtiöt ovat alusta asti sietäneet ja jopa kannustaneet fanien toimia, osaksi koska fanit ovat noudattaneet omia sääntöjään, joiden on tarkoitus estää fanikäännösten levitys virallisen lisensoinnin jälkeen. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected]

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2006 Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Recommended Citation Endresak, David, "Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture" (2006). Senior Honors Theses. 322. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture Degree Type Open Access Senior Honors Thesis Department Women's and Gender Studies First Advisor Dr. Gary Evans Second Advisor Dr. Kate Mehuron Third Advisor Dr. Linda Schott This open access senior honors thesis is available at DigitalCommons@EMU: http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 GIRL POWER: FEMININE MOTIFS IN JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE By David Endresak A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Eastern Michigan University Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in Women's and Gender Studies Approved at Ypsilanti, Michigan, on this date _______________________ Dr. Gary Evans___________________________ Supervising Instructor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Kate Mehuron_________________________ Honors Advisor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Linda Schott__________________________ Dennis Beagan__________________________ Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Heather L. S. Holmes___________________ Honors Director (Print Name and have signed) 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Printed Media.................................................................................................. -

Sample File an Alien Menace Descends Upon the SDF-1 in Droves

Sample file An alien menace descends upon the SDF-1 in droves. You, your friends, and the might of Robotechnology are the only things that stand between them and seventy thousand innocent civilians. Do not expect to make it home. Do not expect to see your friends again. Do whatever it takes to ensure humanity’s future. Welcome to Robotech. Sample file Robotech: The Macross Saga The Roleplaying Game 1st Edition - Version1.0 Game Design: Jeff Mechlinski Scenario Writing: Bryan Young Illustrations: Francisco Etchart Copy Editor: Keith Garrett Lore Editor / Contributing Writing: Martin Hanze Narrative Rules: Oscar Simmons ASC Logo: Dave Killingsworth Special Thanks: Ryan Call, Chris Czerniak, Darius Hambleton, Jeff Lyons, Mike Hamilton, Alex Rothbaum, Nathan Shaw, Mike Lent, Aaron Bryant, Jeff Rossiter, Leigh George Kade, Mark Middlemas,Sergio Garcia Troyano, Ian Gray, Henry Walters, Alexander Miller, Robert Jeppesen, Thomas Walters, Justin Grulke, Jeff Farrar, Paul Bachleda, Juan Francisco Torres & The Ancient Papichulos, Deanna Buhlman, Jessica Frost, Blake Sheets Our Gen Con 2019 Players. Special Acknowledgement: Carl Macek, Tommy Yune, Noboru Ishiguro, Kenichi Matsuzaki, Kazutaka Miyatake, Shoji Kawamori, and Haruhiko Mikimoto. ROBOTECH © 1985, 2019 Harmony Gold USA, Inc. All Rights Reserved. ROBOTECH®, MACROSS®, and all associated names, characters and related indicia are trademarks of Harmony Gold USA, Inc. All Rights Reserved. ISBN Digital 13: 978-1-988943-79-4 ISBN Physical 13: 978-1-988943-80-0 SampleStrange Machine Games, LLC; 2019 -

Review of the Scottish Animation Sector

__ Review of the Scottish Animation Sector Creative Scotland BOP Consulting March 2017 Page 1 of 45 Contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................... 4 2. The Animation Sector ........................................................................ 6 3. Making Animation ............................................................................ 11 4. Learning Animation .......................................................................... 21 5. Watching Animation ......................................................................... 25 6. Case Study: Vancouver ................................................................... 27 7. Case Study: Denmark ...................................................................... 29 8. Case Study: Northern Ireland ......................................................... 32 9. Future Vision & Next Steps ............................................................. 35 10. Appendices ....................................................................................... 39 Page 2 of 45 This Report was commissioned by Creative Scotland, and produced by: Barbara McKissack and Bronwyn McLean, BOP Consulting (www.bop.co.uk) Cover image from Nothing to Declare courtesy of the Scottish Film Talent Network (SFTN), Studio Temba, Once Were Farmers and Interference Pattern © Hopscotch Films, CMI, Digicult & Creative Scotland. If you would like to know more about this report, please contact: Bronwyn McLean Email: [email protected] Tel: 0131 344 -

A Blue Cat on the Galactic Railroad: Anime and Cosmic Subjectivity

PAUL ROQUET A Blue Cat on the Galactic Railroad: Anime and Cosmic Subjectivity L OOKING UP AT THE STARS does not demand much in the way of movement: the muscles in the back of the neck contract, the head lifts. But in this simple turn from the interpersonal realm of the Earth’s surface to the expansive spread of the night sky, subjectivity undergoes a quietly radical transformation. Social identity falls away as the human body gazes into the light and darkness of its own distant past. To turn to the stars is to locate the material substrate of the self within the vast expanse of the cosmos. In the 1985 adaptation of Miyazawa Kenji’s classic Japanese children’s tale Night on the Galactic Railroad by anime studio Group TAC, this turn to look up at the Milky Way comes to serve as an alternate horizon of self- discovery for a young boy who feels ostracized at school and has difficulty making friends. The film experiments with the emergent anime aesthetics of limited animation, sound, and character design, reworking these styles for a larger cultural turn away from social identities toward what I will call cosmic subjectivity, a form of self-understanding drawn not through social frames, but by reflecting the self against the backdrop of the larger galaxy. The film’s primary audience consisted of school-age children born in the 1970s, the first generation to come of age in Japan’s post-1960s con- sumer society. Many would have first encountered Miyazawa’s Night on the Galactic Railroad (Ginga tetsudo¯ no yoru; also known by the Esperanto title Neokto de la Galaksia Fervojo) as assigned reading in elementary school. -

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid Deutsch Alice Im Wunderland Opening Anne mit den roten Haaren Opening Attack On Titans So Ist Es Immer Beyblade Opening Biene Maja Opening Catpain Harlock Opening Card Captor Sakura Ending Chibi Maruko-Chan Opening Cutie Honey Opening Detektiv Conan OP 7 - Die Zeit steht still Detektiv Conan OP 8 - Ich Kann Nichts Dagegen Tun Detektiv Conan Opening 1 - 100 Jahre Geh'n Vorbei Detektiv Conan Opening 2 - Laufe Durch Die Zeit Detektiv Conan Opening 3 - Mit Aller Kraft Detektiv Conan Opening 4 - Mein Geheimnis Detektiv Conan Opening 5 - Die Liebe Kann Nicht Warten Die Tollen Fussball-Stars (Tsubasa) Opening Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure Wir Werden Siegen (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein (Insttrumental) Digimon Frontier Die Hyper Spirit Digitation (Instrumental) Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt (Instrumental) (Lange Version) Digimon Frontier Wenn Du Willst (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Eine Vision (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Ending - Neuer Morgen Digimon Tamers Neuer Morgen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Regenbogen Digimon Tamers Regenbogen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Sei Frei (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Spiel Dein Spiel (Instrumental) DoReMi Ending Doremi -

Kumoricon 2006 Pocket Programming Guide

Kumoricon 2006 Exhibitors Hall / Main Events Console / LAN / Live 1 / Karaoke Panel 1 Panel 2 Panel 3 Workshop 1 RPG Room Video Art Show Fan Creation Station - 2 - Pocket Programming Guide Kumoricon 2006 Pocket Programming Guide Table of Contents Policies Change and Reference 4 Convention Programming Hours 6 Tickets, Guests, and Exhibitors 7 Video, Panel, and Event Schedules 8 Con Tips 19 Art Contest Entrants 20 Survival Guide 23 - 3 - Kumoricon 2006 Props and Costume Policy Change We regret to announce that due to last-minute changes, Kumoricon policy must be amended as follows: • Absolutely no metal props will be allowed within Kumoricon convention space. This includes but is not limited to prop swords and stage steel. • No masks or other items which obscure an attendee’s face from view may be worn while in the corridors and common areas of the hotel. • No airsoft guns will be permitted. Plastic toy guns are acceptable, if not designed to fire a projectile. Guns must be obvious fakes at a distance of ten feet. • As always, props cannot be brandished in any way. Only when posing for a still photo may props be held in any manner that could be deemed threatening. The staff of Kumoricon extends our apologies to anyone adversely affected by this policy change. If you have any questions, please ask at the peacebonding desk. These policy changes supersede the policies printed in the main convention book. All other policies in the convention book remain in effect. - 4 - Pocket Programming Guide Policies Please be sure to read the full policies in the main convention book.