Robert F. Burk.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law J

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 8 Article 12 Issue 2 Spring Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law J. Gordon Hylton Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation J. Gordon Hylton, Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law, 8 Marq. Sports L. J. 455 (1998) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol8/iss2/12 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS LEGAL BASES: BASEBALL AND THE LAW Roger I. Abrams [Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Temple University Press 1998] xi / 226 pages ISBN: 1-56639-599-2 In spite of the greater popularity of football and basketball, baseball remains the sport of greatest interest to writers, artists, and historians. The same appears to be true for law professors as well. Recent years have seen the publication Spencer Waller, Neil Cohen, & Paul Finkelman's, Baseball and the American Legal Mind (1995) and G. Ed- ward White's, Creating the National Pastime: Baseball Transforms Itself, 1903-1953 (1996). Now noted labor law expert and Rutgers-Newark Law School Dean Roger Abrams has entered the field with Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law. Unlike the Waller, Cohen, Finkelman anthology of documents and White's history, Abrams does not attempt the survey the full range of intersections between the baseball industry and the legal system. In- stead, he focuses upon the history of labor-management relations. -

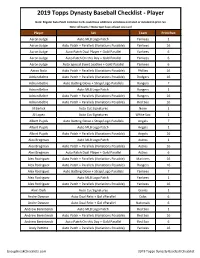

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player Note: Regular Auto Patch Common Cards could have additional variations not listed or included in print run Note: All teams + None Spot have at least one card Player Set Team Print Run Aaron Judge Auto MLB Logo Patch Yankees 1 Aaron Judge Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Yankees 16 Aaron Judge Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Patch On this Day + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Special Event Leather + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Nola Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Phillies 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Dodgers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Rangers 7 Adrian Beltre Auto MLB Logo Patch Rangers 1 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Red Sox 16 Al Barlick Auto Cut Signatures None 1 Al Lopez Auto Cut Signatures White Sox 1 Albert Pujols Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Angels 7 Albert Pujols Auto MLB Logo Patch Angels 1 Albert Pujols Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Angels 16 Alex Bregman Auto MLB Logo Patch Astros 1 Alex Bregman Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Astros 16 Alex Bregman Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Astros 6 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Mariners 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Yankees 7 Alex Rodriguez -

Baseball Autographs Signed 1950-55 Callahans 297 Honus Wagner 9

January 31 Auction: Baseball Autographs Signed 1950-55 Callahans 297 Honus Wagner 9 ............................ 500 Such a neat item, offered is a true high grade hand-signed 290 Fred Clarke 9.5 ......................... 100 Honus Wagner baseball card. So hard to find, we hardly ever Sharp card, this looks to be a fine Near Mint. Signed in par- see any kind of card signed by the legendary and beloved ticularly bold blue ink, this is a terrific autograph. Desirable Wagner. The offered card, slabbed by PSA/DNA, is well signed card, deadball era HOFer Fred Clarke died in 1960. centered with four sharp corners. Signed right in the center PSA/DNA slabbed. in blue fountain pen, this is a very nice signature. Key piece, this is another item that might appreciate rapidly in the 291 Clark Griffith 9 ............................ 150 future given current market conditions. Very scarce signed card, Clark Griffith died in 1955, giving him only a fairly short window to sign one of these. Sharp 298 Ed Walsh 9 ............................ 100 card is well centered and Near Mint or better to our eyes, Desirable signed card, this White Sox HOF pitcher from the this has a fine and clean blue ballpoint ink signature on the deadball era died in 1959. Signed neatly in blue ballpoint left side. PSA/DNA slabbed. ink in a good spot, this is a very nice signature. Slabbed Authentic by PSA/DNA, this is a quality signed card. 292 Rogers Hornsby 9.5 ......................... 300 Remarkable signed card, the card itself is Near Mint and 299 Lot of 3 w/Sisler 9 ..............................70 quite sharp, the autograph is almost stunningly nice. -

2021 Topps Luminaries Baseball Card

2021 Topps Luminaries Baseball Card Totals by Player 211 Players; 117 Players with 16 Hits or More; Other Players with 7 or less Large Multi Player Cards = 10 Players-70 Players on Card Large Multi PLAYER TOTAL AUTO ONLY AUTO RELIC Player Card Aaron Judge 129 68 58 3 Adrian Beltre 38 34 4 Al Barlick 1 1 Al Kaline 2 1 1 Al Simmons 1 1 Albert Pujols 42 34 2 6 Alec Bohm 149 82 67 Alex Bregman 69 68 1 Alex Kirilloff 67 24 43 Alex Rodriguez 182 102 74 6 Andre Dawson 36 34 2 Andrew Benintendi 34 34 Andrew McCutchen 84 68 16 Andrew Vaughn 92 92 Andy Pettitte 35 34 1 Anthony Rendon 68 68 Anthony Rizzo 2 2 Antonin Scalia 1 1 Babe Ruth 2 1 1 Barack Obama 1 1 Barry Larkin 80 34 45 1 Bernie Williams 34 34 Bert Blyleven 34 34 Bob Feller 3 1 1 1 Bob Gibson 1 1 Bob Lemon 1 1 Bobby Dalbec 87 58 29 Bobby Thomson 2 1 1 Brailyn Marquez 34 34 Brooks Robinson 36 34 2 Bryce Harper 162 68 91 3 Buck Leonard 1 1 Buck O'Neil 1 1 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2021 Topps Luminaries Baseball Card Totals by Player Large Multi PLAYER TOTAL AUTO ONLY AUTO RELIC Player Card Buster Posey 160 68 91 1 Byron Buxton 24 24 Cal Ripken Jr. 132 68 59 5 Carl Yastrzemski 131 68 58 5 Carlos Correa 34 34 Carlos Delgado 1 1 Carlton Fisk 34 34 Casey Mize 121 34 87 Casey Stengel 2 1 1 CC Sabathia 35 34 1 Charles Comiskey 1 1 Chipper Jones 133 68 61 4 Christian Yelich 167 68 97 2 Cody Bellinger 3 1 2 Connie Mack 1 1 Corey Seager 20 18 2 Cristian Pache 24 24 Dale Murphy 1 1 Darryl Strawberry 1 1 Dave Parker 1 1 Dave Winfield 3 3 David Ortiz 163 68 92 3 David Wright 35 34 1 Deivi Garcia 58 58 Derek Jeter 38 34 4 Devin Williams 1 1 DJ LeMahieu 1 1 Don Drysdale 1 1 Don Mattingly 64 34 29 1 Duke Snider 1 1 Dylan Carlson 59 58 1 Earl Averill 1 1 Eddie Mathews 2 1 1 Eddie Murray 66 34 29 3 Edgar Martinez 98 68 29 1 Eloy Jimenez 84 82 1 1 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2021 Topps Luminaries Baseball Card Totals by Player Large Multi PLAYER TOTAL AUTO ONLY AUTO RELIC Player Card Enos Slaughter 1 1 Ernie Banks 1 1 Fernando Tatis Jr. -

The Irish in Baseball ALSO by DAVID L

The Irish in Baseball ALSO BY DAVID L. FLEITZ AND FROM MCFARLAND Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (Large Print) (2008) [2001] More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little-Known Greats at Cooperstown (2007) Cap Anson: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (2005) Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Little-Known Members of the Hall of Fame (2004) Louis Sockalexis: The First Cleveland Indian (2002) Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (2001) The Irish in Baseball An Early History DAVID L. FLEITZ McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Fleitz, David L., 1955– The Irish in baseball : an early history / David L. Fleitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3419-0 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball—United States—History—19th century. 2. Irish American baseball players—History—19th century. 3. Irish Americans—History—19th century. 4. Ireland—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. 5. United States—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. I. Title. GV863.A1F63 2009 796.357'640973—dc22 2009001305 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 David L. Fleitz. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: (left to right) Willie Keeler, Hughey Jennings, groundskeeper Joe Murphy, Joe Kelley and John McGraw of the Baltimore Orioles (Sports Legends Museum, Baltimore, Maryland) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Acknowledgments I would like to thank a few people and organizations that helped make this book possible. -

A Whole New Ball Game: Sports Stadiums and Urban Renewal in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and St

A Whole New Ball Game: Sports Stadiums and Urban Renewal in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis, 1950-1970 AARON COWAN n the latter years of the 1960s, a strange phenomenon occurred in the cities of Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis. Massive white round Iobjects, dozens of acres in size, began appearing in these cities' down- towns, generating a flurry of excitement and anticipation among their residents. According to one expert, these unfamiliar structures resembled transport ships for "a Martian army [that] decided to invade Earth."1 The gigantic objects were not, of course, flying saucers but sports stadiums. They were the work not of alien invaders, but of the cities' own leaders, who hoped these unusual and futuristic-looking structures would be the key to bringing their struggling cities back to life. At the end of the Second World War, government and business leaders in the cities of Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St. Louis recognized that their cities, once proud icons of America's industrial and commercial might, were dying. Shrouded in a haze of sulphureous smoke, their riparian transportation advantages long obsolete, each city was losing population by the thou- sands while crime rates skyrocketed. Extensive flooding, ever the curse of river cities, had wreaked havoc on all three cities' property values during 1936 and 1937, compounding economic difficulties ushered in with the Riverfront Stadium in Great Depression. While the industrial mobilization of World War II had Cincinnati. Cincinnati brought some relief, these cities' leaders felt less than sanguine about the Museum Center, Cincinnati Historical Society Library postwar future.2 In 1944, the Wall Street Journal rated Pittsburgh a "Class D" city with a bleak future and little promise for economic growth. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Manning, Jackson Snap USDESEA Marks

Page 26 THE STARS AND STRIPES Saturday, May 6, 1972 Manning, Jackson Snap USDESEA Marks By AUBREY ROBINSON old record ot 4:05.6 set last with Manning and Jackson was Arnolc to win the 100 meters son also jumped 5-8, but did it Staff Writer year by Bitburg's Bill Teasley. Munich's Dan Thomas, a by a half step. Both logged on his third try to finish third. MUNICH (S&S) — (Teasley won his 800-meter triple-winner who took firsts in times of 11.4 seconds. Anchorman Ron Baskin, Stuttgart's Tom Manning and heat in the Northern Regionals the 100 and 200 meters and the The fleet Thomas and about five vards behind when Heidelberg's George Jackson at Berlin, and was not sched- long jump. He placed second in Seymour staged duels in the he got the baton, turned in a cracked USDESEA records to uled for action in the 1500 until the 400 meters. 200 and 400 meters with blistering finish to bring Hei- highlight the 1972 Southern re- Saturday.) Jackson and Stuttgart's Sid Thomas taking the former in delberg victory in the 1600 gional prep track and field Stuttgart rode the strength of Seymour won two events each. 26.0 and Seymour the latter in meter relay. Jeff Weil, Bob championships here Friday. six firsts to capture Class A In the record-shattering per- 51.2. Montgomery and Daniels Manning, a senior, lowered team laurels with 69 points. formance of Manning, runner- Also winning the long jump teamed with Baskin for a time the standard for the 3200 Runnerup Heidelberg, which up Bob Montgomery of Heidel- with a leap of 21 feet, 1% of 3 minutes, 33.2 seconds to meters almost seven seconds had three firsts and five sec- berg also bettered the old 3200 inches, Thomas accounted for barely nip Karlsruhe at the in recording a time of 9 min- onds, totaled 48. -

Says Organized Crime Aided Defeat of Track TRENTON (AP) - a Legis- Mittee Also Heard from Rob- Hearing," Sen

Today: Fall Home Improvement Section -SEE SECOND SECTION Sunny, Pleasant Sunny and pleasant today. THEDAILY HOME Clear and cool again tonight. Mostly sunny and mild tomor- Red Bank, Freehold row. Long Branch FINAL (Bc» Details Paga 2) Monmouth County9g Home Newspaper tor 9 Yearn VOL. 91, NO. 57 RED BANK, N. J., TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 1968 TEN CENTS Black Youths' Protest Halts Board Ad j our nment MATAWAN TOWNSHIP - The black yn- -sters - 80 The surge of young black students occurred when John Hinear a question some board members considered insulting. sitting on this school board." or 90 of them — last night surged toward stage, fists J. Bradley, Board of Education president, suddenly de- "How much black history did you learn in the Mata- Another "O-o-o-o-h!" arose from the audience as Mr. upraised, shouting, "We shall overcome!" . "No, no, no!" clared the board meeting adjourned during an exchange wan school system — and I imagine, looking at you, it was Bradley's gavel ended Ihe meeting. "We're going to take what we want, that's all!" Miss between Jonah C. Person of 86 Highfield Ave., a black a long time ago . ." he began. APPEAR SHAKEN Barbara Williams of Cliffwood shouted. parent, and Mrs. Esther Rinear, a school board member. "O-o-o-o-h!" A shocked wail rose from the youngsters. Appearing shaken by the surge of black students to the The angry students started to swarm up over the stage, There was silence for a few seconds after Mr. Bradley's "It was a long time for me, too," Mr. -

VA/Imp the Oall /[Siffibstm > a ; Coco / 1 Mtmr ¦*2*7S Wiijon It Vo Salary Expected

¦Vs "- '¦'***» **»*¦*.>*+¦¦¦¦ v» «•**•*> «¦ Redskins Play Champs •MBS? * "* Like ij9 BB »S Pct| MjQ " mJ&r * :|r • Jfty In Triumph Over Cardinals Colts, Browns Kuharich Wants Sfaf Improvement for Front, Eight Giants Sunday In By LEWIS F. ATCHISON Bt»r Staff Correspondent ! CHICAGO, Oct. 7 —The Red- PORTS skins pet formed like champions Sf• Tied for Second in rolling over the Cardinals, THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C. 37-14. yesterday. MONDAY. Os TORI K 7. |*A7 By th# Aa roc .a >d ?rtn here But with A-18 New Giants, The upstart and unbeaten the York last years pro champs. Invading Baltimore Colts the and back- Griffith home-again Cleveland Biowns Stadium next Sundav to help today were a step a launch the season in ahead of Washington, Joe Mathews logiam of eight National Foot- Coach Kuha- Makes rich plan ball League teams doesn’t to let the -quad The Colts pare the Western rest on its laurels "This is far from a polished division " and the Browns the ball club Kuharich Eastern division with rec- said “and * Milwaukee Flip Lid 2-0 \ \ g|| ords The rest of pkigs -j /JF .1# * \ the league \ ™ pa ¦ . tw -a RR^^H \ 1i ¦¦ g* \ is | w» jr fj^». a Bv CHARI.KS M. KG AN a 3-and-2 eount on the batter. virtually in one big second STATISTICS place tie after play. Sports Ed*?or of The £ sr That tied the score 4-4 but the week end Rednt Car-.* Yesterdays results Pint donni j ?» MILWAUKEE, Oct. Braves syli had another turn com- H ' 7 This pounded tangle »rGBf« '?4 •>, the a< last »•*« •‘‘.r,* y»fO«*f ’*m 4 ", baseball - mad community at bn t. -

Russians Want Haiek Dismissed Prof. Will Take Office If Necessary Infantrymen Rescue Engineer Teams

LOtI TIDE HIGH.. TIDE 9-19-68 9-19-68 0.6 AT 215~ 5.7 AT 0330 0.5 AT 0948 5.3 AT 1554 t-iOURGlASS FILLS SENATE VAC- r!Lan--_L Writ.s Letter Suitab'e Rep'acemen' Nor bailable ANC'--R,p. c, •• ,',..... IItJIl JAM"- Goom,TOWN, N. "Y OJ TALKS Respo ....,..... to Australl"a TO NEWSMEN IN AL_ Russians Want Haiek Dismissed BANY ArTER Gov. SYDNEY (UPI )--PRINCE NOROOOM 5IHANOUk, PRAGUE (UPI )~~ WANTED ONE FOREIGN MINISTER WHO WILL BE AMENABLE TO THE ROCKEFELLER "1'- EF OF STATE OF CAMBODIA, IN A LETTER SOVIET UNION AND CENSORS W~O WILL BE ABLE TO WORK WITH CZECH EDITORS. POINTED HIM TO THE EDITOR ,"UBLISH£() TOOAY IN THE THESE WERE THE PERSONNEL NEEDS OF BOTH COUNTRIES TODAY AND FAILURE SO FAR TO FILL THE U.S. '<"'_\::~;'~::=::L, NEWSPAPER" AUSTRAliAN, SAID 'IND SUITABLE APPLICANTS 1$ AGGRAVATING TENSIONS, OBSERVERS SAID. ATE SEAT O' TH~ CHINA NOR ANY OTHER POWER WOULD THE SOVIETS WANT TO DISHISS JIRI HA~EK AS CZECH FOREIGN MINISTER, BUT HAVE lATE ROBERT f. BE ALLOWED TO INFLUENCE HIS COUNTRY'S DtLAYtO HIS RtMOVAL BtCAUSE THt CZECHS CANNOT FIND A SUCCtSSOR ACCEPTAaLE TO KENNtDV. HIS AP- POLICIES. THE Russ I ANS POINTMENT WAS A SIHANOUK WROTE TO THE AUSTRALIAN IN RUSSIANS OtHANrED THAT HAJEK Bt .IRED, SOURCES SAID, BECAUSE or HIS ACTIV SURPRISE TO MANV, I"'po", TO COMMENTS MADE 8Y BOOK RE ITI[S AT THE UNITE) NATIONS DURING THE EARLY STAGES Of THE OCCUPATION. VIEWER J. L. G'RlING ••• ANO WHICH WERE CZECH LEADERS PROPOSED VACLAV CARRIED BY THE NEWSPAPER ••• IN CONJUNC WHO IS NOW ASSISTANT rOREIGN MINISTER Premier Sa'azar's Successor Appointed WITH THE PUBLICATION OF THE BOOK, SUT THE ~OV":::TS REfUSED HiM FOR SECI.IIITY.