Asexual People's Experience with Microaggressions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

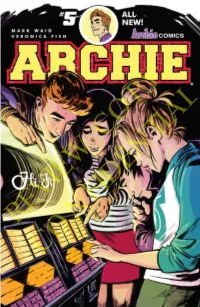

Jughead Jones. Copy

COPY: REVIEW CONFIDENTIAL Archie Andrews and Betty Cooper haven’t spoken since the infamous #LipstickIncident that broke them apart over the summer, and Betty’s having a rough time seeing him get over their relationship and move on with new girl Veronica Lodge. Even worse, their budding relationship is making Archie’s best friend Jughead Jones downright crazy. They have to step in and do SOMETHING, but Jughead’sCOPY: not so sure about who they’ve chosen to do their dirty work… STORY BY ART BY MARK WAID VERONICA FISH COLORING BY LETTERING BY ANDRE SZYMANOWICZ JACK MORELLI With JEN VAUGHN REVIEWPUBLISHER EDITOR JON GOLDWATER MIKE PELLERITO Publisher / Co-CEO: Jon Goldwater Co-CEO: Nancy Silberkleit President: Mike Pellerito Co-President / Editor-In-Chief: Victor Gorelick Chief Creative Officer: Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa Chief Operating Officer: William Mooar Chief Financial Officer:CONFIDENTIAL Robert Wintle SVP – Publishing and Operations: Harold Buchholz SVP – Publicity & Marketing: Alex Segura SVP – Digital: Ron Perazza Director of Book Sales & Operations: Jonathan Betancourt Production Manager: Stephen Oswald Production Assistant: Isabelle Mauriello Proofreader / Editorial Assistant: Jamie Lee Rotante ARCHIE (ISSN:07356455), Vol. 2, No. 5, February, 2016. Published monthly by ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS, INC., 629 Fifth Avenue, Suite 100, Pelham, New York 10803-1242. Jon Goldwater, Publisher/Co-CEO; Nancy Silberkleit, Co-CEO; Mike Pellerito, President; Victor Gorelick, Co-President. ARCHIE characters created by John L. Goldwater. The likenesses of the original Archie characters were created by Bob Montana. Single copies $3.99. Subscription rate: $47.88 for 12 issues. All Canadian orders payable in U.S. funds. “Archie” and the individual characters’ names and likenesses are the exclusive trademarks of Archie Comic Publications, Inc. -

Asexuality 101

BY THE NUMBERS Asexual people (or aces) experience little or no 28% sexual attraction. While most asexual people desire emotionally intimate relationships, they are not drawn to sex as a way to express that intimacy. of the community is 18 or younger ASEXUALITY ISN’T ACES MIGHT 32% Abstinence because of Want friendship, a bad relationship understanding, and Abstinence because of empathy religious reasons Fall in love of the community are between 19 and 21 Celibacy Experience arousal and Sexual repression, orgasm aversion, or Masturbate 19% dysfunction Have sex Loss of libido due to Not have sex age or circumstance Be of any gender, age, Fear of intimacy or background of the community are currently Inability to find a Have a spouse and/or in high school partner children 40% of the community are in college Aromantic – people who experience little or no romantic 20% attraction and are content with close friendships and other non-romantic relationships. Demisexual – people who only experience sexual attraction of the community identify as once they form a strong emotional connection with the person. transgender or are questioning Grey-A – people who identify somewhere between sexual and their gender identity asexual on the sexuality spectrum. 41% Queerplatonic – One type of non-romantic relationship where there is an intense emotional connection going beyond what is traditionally thought of as friendship. Romantic orientations – Aces commonly use hetero-, homo-, of the community identify as part of the LGBT community bi-, and pan- in front of the word romantic to describe who they experience romantic attraction to. Source: Asexy Community Census http://www.tinyurl.com/AsexyCensusResults Asexual Awareness Week Community Engagement Series – Trevor Project | Last Updated April 2012 ACE SPECIFIC Feeling e mpty, isolated, Some aces voice a fear of ISSUES and/or alone. -

Asexuality: a Mixed-Methods Approach

Arch Sex Behav (2010) 39:599–618 DOI 10.1007/s10508-008-9434-x ORIGINAL PAPER Asexuality: A Mixed-Methods Approach Lori A. Brotto Æ Gail Knudson Æ Jess Inskip Æ Katherine Rhodes Æ Yvonne Erskine Received: 13 November 2007 / Revised: 20 June 2008 / Accepted: 9 August 2008 / Published online: 11 December 2008 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2008 Abstract Current definitions of asexuality focus on sexual having to ‘‘negotiate’’ sexual activity. There were not higher attraction, sexual behavior, and lack of sexual orientation or rates of psychopathology among asexuals; however, a subset sexual excitation; however, the extent to which these defi- might fit the criteria for Schizoid Personality Disorder. There nitions are accepted by self-identified asexuals is unknown. was also strong opposition to viewing asexuality as an ex- The goal of Study 1 was to examine relationship character- treme case of sexual desire disorder. Finally, asexuals were istics, frequency of sexual behaviors, sexual difficulties and very motivated to liaise with sex researchers to further the distress, psychopathology, interpersonal functioning, and scientific study of asexuality. alexithymia in 187 asexuals recruited from the Asexuality Visibility and Education Network (AVEN). Asexual men Keywords Asexuality Á Sexual identity Á Sexual (n = 54) and women (n = 133) completed validated ques- orientation Á Sexual attraction Á Romantic attraction Á tionnaires online. Sexual response was lower than normative Qualitative methodology data and was not experienced as distressing, and masturba- tion frequency in males was similar to available data for sexual men. Social withdrawal was the most elevated per- Introduction sonality subscale; however, interpersonal functioning was in the normal range. -

Nonparaphilic Sexual Addiction Mark Kahabka

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 63 | Number 4 Article 2 11-1-1996 Nonparaphilic Sexual Addiction Mark Kahabka Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Kahabka, Mark (1996) "Nonparaphilic Sexual Addiction," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 63: No. 4, Article 2. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol63/iss4/2 Nonparaphilic Sexual Addiction by Mr. Mark Kahabka The author is a recent graduate from the Master's program in Pastoral Counseling at Saint Paul University in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Impulse control disorders of a sexual nature have probably plagued humankind from its beginnings. Sometimes classified today as "sexual addiction" or "nonparaphilic sexual addiction,"l it has been labeled by at least one professional working within the field as "'The World's Oldest/Newest Perplexity."'2 Newest, because for the most part, the only available data until recently has come from those working within the criminal justice system and as Patrick Carnes points out, "they never see the many addicts who have not been arrested."3 By definition, both paraphilic4 and nonparaphilic sexual disorders "involve intense sexual urges and fantasies" and which the "individual repeatedly acts on these urges or is highly distressed by them .. "5 Such disorders were at one time categorized under the classification of neurotic obsessions and compulsions, and thus were usually labeled as disorders of an obsessive compulsive nature. Since those falling into this latter category, however, perceive such obessions and compulsions as "an unwanted invasion of consciousness"6 (in contrast to sexual impulse control disorders, which are "inherently pleasurable and consciously desired"7) they are now placed under the "impulse control disorder" category.s To help clarify the distinction: The purpose of the compulsions is to reduce anxiety, which often stems from unwanted but intrusive thoughts. -

Flag Definitions

Flag Definitions Rainbow Flag : The rainbow flag, commonly known as the gay pride flag or LGBTQ pride flag, is a symbol of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer pride and LGBTQ social movements. Always has red at the top and violet at the bottom. It represents the diversity of gays and lesbians around the world. Bisexual Pride Flag: Bisexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behaviour toward both males and females, or to more than one sex or gender. Pink represents sexual attraction to the same sex only (gay and lesbian). Blue represents sexual attraction to the opposite sex only (Straight). Purple represents sexual attraction to both sexes (bi). The key to understanding the symbolism of the Bisexual flag is to know that the purple pixels of colour blend unnoticeably into both pink and blue, just as in the “real world” where bi people blend unnoticeably into both the gay/lesbian and straight communities. Transgender Pride Flag: Transgender people have a gender identity or gender expression that differs from their assigned sex. Blue stripes at top and bottom is the traditional colour for baby boys. Pink stipes next to them are the traditional colour for baby girls. White stripe in the middle is for people that are nonbinary, feel that they don’t have a gender. The pattern is such that no matter which way you fly it, it is always correct, signifying us finding correctness in our lives. Intersex Pride Flag: Intersex people are those who do not exhibit all the biological characteristics of male or female, or exhibit a combination of characteristics, at birth. -

![8A1h4 [Pdf Free] Jughead Vol. 1 Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0710/8a1h4-pdf-free-jughead-vol-1-online-870710.webp)

8A1h4 [Pdf Free] Jughead Vol. 1 Online

8a1h4 [Pdf free] Jughead Vol. 1 Online [8a1h4.ebook] Jughead Vol. 1 Pdf Free Chip Zdarsky ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #112812 in Books Archie Comics 2016-07-26 2016-07-26Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 10.20 x .40 x 6.70l, .81 #File Name: 1627388931168 pagesArchie Comics | File size: 41.Mb Chip Zdarsky : Jughead Vol. 1 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Jughead Vol. 1: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Great comic. I read some of the older Jughead ...By CustomerGreat comic. I read some of the older Jughead comics and always enjoyed them. This new run is updated for 2017 without it being forced. The integration of queer characters is well done and wonderful. The spirit of Jughead's imagination and adventures is alive and well in these comics with their fun plotlines and lovely artwork.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. The Archie Reboot continues with Jughead!By samaritanxDecent reboot of a classic charcter, but the stories and artwork were not as strong as some of the other more recent reboots of the other canon Archie characters. I did enjoy seeing The Man from R.I.V.E.R.D.A.L.E. and Captain Pureheart spoofs, even if they were only daydreams in Jughead's imagination.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Jughead's Back!By JanaeI gave this five stars because it gave me everything I want from Jughead and nothing I didn't. -

Asexualities, Intimacies and Relationality

Asexualities, Intimacies and Relationality Tiina Vares Introduction Romantic asexual, aromatic asexual, grey-asexual and demi-sexuali are just some of the identity categories which sit under the umbrella of asexuality. Since the founding of the online site AVEN (Asexual Visibility and Education Network) in 2001, we have seen the development of an asexual movement in primarily western liberal democracies. While AVEN defines an asexual individual as a person “who does not experience sexual attraction”, the terms above highlight a diversity with the ways in which asexual identified people experience and define their asexuality. This diversity includes different kinds of attraction, different ways of desiring and seeking out interpersonal relationships, and a range of intimacies, physical and otherwise (Gupta and Cerankowski, 2017). While research into asexuality has increased rapidly in the past two decades, there has been little academic attention to how asexual people conceive of and practice intimacy and relationships (Dawson et al., 2016). In this chapter I add to the small body of academic scholarship that has focused on the experiences of friendship, relationships and intimacy of self-identified asexuals (Haeffner, 2011; Van Houdenhove et al. 2015; Dawson et al., 2016; Vares, 2018). Based on my research with 15 self-identified asexuals, aged 18 to 60 years, and living in New Zealandii (see Vares, 2018), I explore the ways in which participants are “actively and creatively renegotiating the boundaries of the platonic, the intimate and the sexual” (Carrigan, 2011, p. 476). I first consider the significance of friends in participants’ lives and, in particular, the ways in which the boundary between friend/partner and friendship/relationship is being disrupted. -

Genders & Sexualities Terms

GENDERS & SEXUALITIES TERMS All terms should be evaluated by your local community to determine what best fits. As with all language, the communities that utilize these and other words may have different meanings and reasons for using different terminology within different groups. Agender: a person who does not identify with a gender identity or gender expression; some agender-identifying people consider themselves gender neutral, genderless, and/or non- binary, while some consider “agender” to be their gender identity. Ally/Accomplice: a person who recognizes their privilege and is actively engaged in a community of resistance to dismantle the systems of oppression. They do not show up to “help” or participate as a way to make themselves feel less guilty about privilege but are able to lean into discomfort and have hard conversations about being held accountable and the ways they must use their privilege and/or social capital for the true liberation of oppressed communities. Androgynous: a person who expresses or presents merged socially-defined masculine and feminine characteristics, or mainly neutral characteristics. Asexual: having a lack of (or low level of) sexual attraction to others and/or a lack of interest or desire for sex or sexual partners. Asexuality exists on a spectrum from people who experience no sexual attraction nor have any desire for sex, to those who experience low levels of sexual attraction and only after significant amounts of time. Many of these different places on the spectrum have their own identity labels. Another term used within the asexual community is “ace,” meaning someone who is asexual. -

Passing When Asexual: Methods for Appearing Straight

Passing When Asexual: Methods for Appearing Straight Taylor Rossi Before Bogaert’s 2004 landmark study, asexuality was a relatively unexplored fringe area of sexual identity. Prior to Bogaert, the only work that had significantly acknowledged asexuality was the famed Kinsey Scale, which had labeled it as “no socio-sexual contacts or reactions” (Kinsey 1948). Asexuality is still a largely unknown and under-researched sexuality. In short, an asexual person is someone who does not experience sexual attraction to anyone. It is often confused with celibacy or chastity due to a lack of understanding, or incorrectly diagnosed by psychologists as hypoactive sexual desire disorder or HSDD (Bogaert 2015). For those reasons asexuality can be difficult to understand, even to those who identify with it, leaving researchers and participants alike with more questions than there are academic answers. Asexuality is a sexual identity in the same way that homosexuality, pansexuality, bisexuality, etc are and therefore exhibits similar trends and rituals. Such rituals include coming out, or the alternative – passing. Passing preserves the status quo of heterosexuality, but is often associated with uncertainty, disillusionment, and self-doubt on the part of the person passing (Chow and Cheng 2010). In a world so sexualized, from advertisements to TV shows and movies, the discovery and acceptance (or lack thereof) of one's asexuality is often shrouded with uncertainty. It is due to this uncertainty and lack of information that more research on asexuality be done and prompting the question, what passing methods are used by those in the asexual community? This question is answered using the testimonies of eight participants, as well as existing research on the topic, and the researcher's own power of implication. -

LOU SCHEIMER: CREATING the FILMATION GENERATION 1946–1948Chapter TWO Driving Japan Crazy

CONTENTS... PREFACE ..........................................5 chapter seventeeN ......149 Anthologies and Expansion (1978–1979) chapter one .............................7 Wherein My Father Punched Out Adolf Hitler Years chapter eighteen .....161 Before Captain America Did (1928–1946) The Year of Legal Discontent (1979–1980) chapter two ..........................17 chapter nineteen .....171 Driving Japan Crazy (1946–1948) Silver Bullets and Soccer Balls (1980–1981) chapter three .................23 chapter twenty ..........179 Carnegie and an Early Proposal (1948–1955) Forced To Runaway (1981–1982) chapter FOUR .....................31 chapter twenty-one ....189 Clowns, Cats, Rockets, and Jesus (1955–1965) A Farewell to Networks / The Last Man Standing (1982–1983) chapter five ........................43 And Who, Disguised As A Real Animation Studio… chapter twenty-two ....197 We Have the Power! (1983–1984) chapter six ............................51 The Super Superheroes (1967) COLOR GALLERY ..............209 chapter seven .................59 The Fantastic Shrinking Bat-Teenager (1968) chapter twenty-three ....521 Morals and Media Battles (1984–1985) chapter eight ....................69 Gold Records and Witches (1969) chapter twenty-four ....223 Sisters Are Doing it for Themselves (1985–1986) chapter nine ........................75 Hey Lady! More Monsters & Music! (1970–1971) chapter twenty-five ......235 Let’s Go Ghostbusters! (1986-1987) chapter ten .........................81 Funnies, Games, and Fables (1971) chapter twenty-six ......241 -

Mental Health and Interpersonal Functioning in Self-Identified Asexual

Psychology & Sexuality,2013 Vol. 4, No. 2, 136–151, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.774162 Mental health and interpersonal functioning in self-identified asexual men and women Morag A. Yulea*,LoriA.Brottob and Boris B. Gorzalkaa aDepartment of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada; bDepartment of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada (Received June 2011; final version received December 2011) Human asexuality is defined as a lack of sexual attraction to anyone or anything, and preliminary evidence suggests that it may best be defined as a sexual orientation. As asexual individuals may face the same social stigma experienced by gay, lesbian and bisexual persons, it follows that asexual individuals may experience higher rates of psychiatric disturbance that have been observed among these non-heterosexual indi- viduals. This study explored mental health correlates and interpersonal functioning and compared asexual, non-heterosexual and heterosexual individuals on these aspects of mental health. Analyses were limited to Caucasian participants only. There were sig- nificant differences among groups on several measures, including depression, anxiety, psychoticism, suicidality and interpersonal problems, and this study provided evidence that asexuality may be associated with higher prevalence of mental health and interper- sonal problems. Clinical implications are indicated, in that asexual individuals should be adequately assessed for mental health difficulties and provided -

Agender Ally Androgynous Androgyne Androsexual/Androphilic Asexual

Terminology Agender Someone who does not identify with any sort of gender identity. This term may also be used by someone who intentionally has no recognizable gender presentation. Some people use similar terms such as “genderless” and “gender neutral”. Ally A Safe Zone ally honors sexual diversity, challenges heterosexist and cissexist remarks and behaviors, and explores and understands these forms of bias within their experiences. This person also works to end oppression personally and professionally through support and advocacy of an oppressed population. In this context Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, Questioning, Intersex, Ally and Asexual individuals Androgynous This word describes both a gender identity as well as a manner of gender presentation. Those who identify as androgynous may identify as between man and woman or something else entirely. Those who present androgynous may dress in a manner that incorporates clothing that is traditionally for men and clothing that’s traditionally for women Androgyne An androgyne is a person who does not fit cleanly into the typical masculine and feminine gender roles of their society. Many androgynes identify as being mentally "between" male and female, or as entirely genderless. The former may also use the term bigender or ambigender, the latter non-gendered or agender. They may experience mental swings between genders, sometimes referred to as being gender fluid Androsexual/Androphilic Attracted to males, men, and/or masculinity Asexual A person who does not experience sexual attraction or has lost interest in sex but may still have romantic interests Bigender A person who fluctuates between traditionally “woman” and “man” gender-based behavior and identities, identifying with both genders (and sometimes a third gender) Binary Gender a traditional and outdated view of gender, limiting possibilities to “man” and “woman” Binary Sex a traditional and outdated view of sex, limiting possibilities to “female” or “male” Biological Sex The classification of people as male, female, or intersex.