Consuming Pop Music/Constructing a Life World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music, Music, Music! Four Stages of Music at El Dorado County Fair

For Immediate Release: June 11, 2019 PLACERVILLE Contact: Jody Gray, El Dorado County Fair CEO at 530.621.5860 or JUNE 13 - 16 Suzanne Wright at [email protected] 100 Fairgrounds Drive, Placerville, CA 95667 High Res Photos: flickr.com/photos/eldoradocountyfair/ collections/72157617020789903/ El Dorado County Fair & Event Center a 501 (c) (3) Nonprofit | eldoradocountyfair.org Music, Music, Music! Four Stages of Music at El Dorado County Fair Placerville, CA – Are you a little bit country and a little bit rock ‘n roll? El Dorado County Fair has that to offer and so much more! With so many stages and genres, El Dorado County Fair is sure to have just what you are looking for. Thursday’s Lineup Stevie Nicks & Fleetwood Mac Tribute featuring Halie O’Ryan—Listening to Halie perform Stevie Nicks with your eyes closed makes it easy to believe that you are listening to Stevie herself. “Oh, mirror in the sky, what is love? Can the child within my heart rise above?” Halie brings oodles of energy and happiness to the stage. Experience the magic of this tribute to Stevie Nicks and Fleetwood Mac, Thursday night at El Dorado County Fair on the Budweiser Community Stage. South 65 is a solid, country/rock, kickabilly band of seasoned musicians and longtime friends. They are a bit of an anomaly due to varying influences and experience, there is almost no song they don’t know or can’t play. They amaze audiences with their penchant for accepting song requests and wow crowds in the process. How many bands can handle a request to play an Alice in Chains tune and then an old Elvis song? Pocket Change is a three-piece band featuring guitar, mandolin and double bass playing Americana, bluegrass, rockabilly and traditional country. -

Front Matter Template

Copyright by Paxton Christopher Haven 2020 The Thesis Committee for Paxton Christopher Haven Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Thesis: Oops…They Did It Again: Pop Music Nostalgia, Collective (Re)memory, and Post-Teeny Queer Music Scenes APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Suzanne Scott, Supervisor Curran Nault Oops…They Did It Again: Pop Music Nostalgia, Collective (Re)memory, and Post-Teeny Queer Music Scenes by Paxton Christopher Haven Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2020 Dedication To my parents, Chris and Fawn, whose unwavering support has instilled within me the confidence, kindness, and sense of humor to tackle anything my past, present, and future may hold. Acknowledgements Thank you to Suzanne Scott for providing an invaluable amount of time and guidance helping to make sense of my longwinded rants and prose. Our conversations throughout the brainstorming and writing process, in addition to your unwavering investment in my scholarship, made this project possible. Thank you to Curran Nault for illustrating to me the infinite potentials within merging the academic and the personal. Watching you lead the classroom with empathy and immense consideration for the lives, legacies, and imaginations of queer and trans artists/philosophers/activists has made me a better scholar and person. Thank you to Taylor for enduring countless circuitous ramblings during our walks home from weekend writing sessions and allowing me the space to further form my thoughts. -

Rise of the Rock Clones • These Days You Don't Have to Stalk the Wilds to Climb Some of the Sport's Most Popular Rocks, Reports Shermakaye Bass

Rise of the rock clones • These days you don't have to stalk the wilds to climb some of the sport's most popular rocks, reports Shermakaye Bass. It's a whole new wall game. Shermakaye Bass - February 1, 2005 As fielding posson approaches the Feather, a notoriously hard bouldering route at Hueco Tanks State Park in Texas, he visualizes the sequence of moves, imagining each foothold, hand pocket and ridiculous undercling. Then he mounts, climbing quickly and fluidly, powering out from the deep hollow at the boulder's base, to the massive bulge with its slopey pockets, and up to the head wall, with its fossil-like feather pattern. Finally, he tops out 12 feet above the crash pads at Austin Rock Gym in Austin, Texas. Five hundred miles from the real thing, Posson has this faux Feather wired. The simulated rock route, which debuted four years ago, gives him and other Austin climbers a taste of a natural rock icon without a plane ticket or a leg- numbing all-night drive. "The movement is definitely the same as the Feather," says Clayton Reagan, an Austin-based climber who has done the real Hueco problem climb many times. The rock gym version, he adds, "is easier, but it's still difficult." A climbing gym in Boulder, Colo., has taken rock simulation further afield. The Spot replicates the geology of famed climbing areas from Hueco to Yosemite to France's Fontainebleau. The gym lets climbers come out of the cold or finger- searing heat and enjoy ideal climbing conditions year-round. -

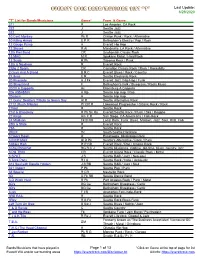

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "T" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre 311 R Los Angeles, CA Rock 322 J Seattle Jazz 322 J Seattle Jazz 10 Cent Monkey Pk R Clinton Punk / Rock / Alternative 10 Killing Hands E P R Bellingham's Electro / Pop / Rock 12 Gauge Pump H Everett Hip Hop 12 Stones R Al Mandeville, LA Rock / Alternative 12th Fret Band CR Snohomish Classic Rock 13 MAG M R Spokane Metal / Hard Rock 13 Scars R Pk Tacoma Rock / Punk 13th & Nowhere R Everett Rock 2 Big 2 Spank CR Carnation Classic Rock / Rock / Rockabilly 2 Guys And A Broad B R C Everett Blues / Rock / Country 2 Libras E R Seattle Electronic Rock 20 Riverside H J Fk Everett Jazz / Hip Hop / Funk 20 Sting Band F Bellingham's Folk / Bluegrass / Roots Music 20/20 A Cappella Ac Ellensburg A Cappella 206 A$$A$$IN H Rp Seattle Hip Hop / Rap 20sicem H Seattle Hip Hop 21 Guns: Seattle's Tribute to Green Day Al R Seattle Alternative Rock 2112 (Rush Tribute) Pr CR R Lakewood Progressive / Classic Rock / Rock 21feet R Seattle Rock 21st & Broadway R Pk Sk Ra Everett/Seattle Rock / Punk / Ska / Reggae 22 Kings Am F R San Diego, CA Americana / Folk-Rock 24 Madison Fk B RB Local Rock, Funk, Blues, Motown, Jazz, Soul, RnB, Folk 25th & State R Everett Rock 29A R Seattle Rock 2KLIX Hc South Seattle Hardcore 3 Doors Down R Escatawpa, Mississippi Rock 3 INCH MAX Al R Pk Seattle's Alternative / Rock / Punk 3 Miles High R P CR Everett Rock / Pop / Classic Rock 3 Play Ricochet BG B C J Seattle bluegrass, ragtime, old-time, blues, country, jazz 3 PM TRIO -

1 the Absent Presence of Progressive Rock in the British Music Press, 1968

The absent presence of progressive rock in the British music press, 1968-1974 Chris Anderton and Chris Atton Abstract The upsurge of academic interest in the genre known as progressive rock has taken much for granted. In particular, little account has been taken of how discourses surrounding progressive rock were deployed in popular culture in the past, especially within the music press. To recover the historical place of the music and its critical reception, we present an analysis of three British weekly music papers of the 1960s and 1970s: Melody Maker, New Musical Express and Sounds. We find that there appears to be relatively little consensus in the papers studied regarding the use and meaning of the term ‘progressive’, pointing to either multiple interpretations or an instability of value judgments and critical claims. Its most common use is to signify musical quality – to connect readers with the breadth of new music being produced at that time, and to indicate a move away from the ‘underground’ scene of the late 1960s. 1 Introduction Beginning in the 1990s there has been an upsurge of academic interest in the genre known as progressive rock, with the appearance of book-length studies by Edward Macan (“Rocking”) and Bill Martin (“Music of Yes”, “Listening”), to which we might add, though not strictly academic, Paul Stump. The 2000s have seen further studies of similar length, amongst them Paul Hegarty & Martin Halliwell, Kevin Holm-Hudson (“Progressive”, “Genesis”) and Edward Macan (“Endless”), in addition to scholarly articles by Jarl A. Ahlkvist, Chris Anderton (“Many-headed”), Chris Atton (“Living”), Kevin Holm-Hudson “Apocalyptic”), and Jay Keister & Jeremy L. -

Xiami Music Genre 文档

xiami music genre douban 2021 年 02 月 14 日 Contents: 1 目录 3 2 23 3 流行 Pop 25 3.1 1. 国语流行 Mandarin Pop ........................................ 26 3.2 2. 粤语流行 Cantopop .......................................... 26 3.3 3. 欧美流行 Western Pop ........................................ 26 3.4 4. 电音流行 Electropop ......................................... 27 3.5 5. 日本流行 J-Pop ............................................ 27 3.6 6. 韩国流行 K-Pop ............................................ 27 3.7 7. 梦幻流行 Dream Pop ......................................... 28 3.8 8. 流行舞曲 Dance-Pop ......................................... 29 3.9 9. 成人时代 Adult Contemporary .................................... 29 3.10 10. 网络流行 Cyber Hit ......................................... 30 3.11 11. 独立流行 Indie Pop ......................................... 30 3.12 12. 女子团体 Girl Group ......................................... 31 3.13 13. 男孩团体 Boy Band ......................................... 32 3.14 14. 青少年流行 Teen Pop ........................................ 32 3.15 15. 迷幻流行 Psychedelic Pop ...................................... 33 3.16 16. 氛围流行 Ambient Pop ....................................... 33 3.17 17. 阳光流行 Sunshine Pop ....................................... 34 3.18 18. 韩国抒情歌曲 Korean Ballad .................................... 34 3.19 19. 台湾民歌运动 Taiwan Folk Scene .................................. 34 3.20 20. 无伴奏合唱 A cappella ....................................... 36 3.21 21. 噪音流行 Noise Pop ......................................... 37 3.22 22. 都市流行 City Pop ......................................... -

Music Guide Music HISTORY There Was a Time When “Elevator Music” Was All You Heard in a Store, Hotel, Or Other Business

Music Guide Music HisTORY There was a time when “elevator music” was all you heard in a store, hotel, or other business. Yawn. 1 1971: a group of music fanatics based out of seattle - known as Aei Music - pioneered the use of music in its original form, and from the original artists, inside of businesses. A new era was born where people could enjoy hearing the artists and songs they know and love in the places they shopped, ate, stayed, played, and worked. 1 1985: DMX Music began designing digital music channels to fit any music lover’s mood and delivered this via satellite to businesses and through cable TV systems. 1 2001: Aei and DMX Music merge to form what becomes DMX, inc. This new company is unrivaled in its music knowledge and design, licensing abilities, and service and delivery capability. 1 2005: DMX moves its home to Austin, TX, the “Live Music capital of the World.” 1 Today, our u.s. and international services reach over 100,000 businesses, 23 million+ residences, and over 200 million people every day. 1 DMX strives to inspire, motivate, intrigue, entertain and create an unforgettable experience for every person that interacts with you. Our mission is to provide you with Music rockstar service that leaves you 100% ecstatic. Music Design & Strategy To get the music right, DMX takes into account many variables including customer demographics, their general likes and dislikes, your business values, current pop culture and media trends, your overall décor and design, and more. Our Music Designers review hundreds of new releases every day to continue honing the right music experience for our clients. -

Phil Spector and the Wall of Sound by Steven Quinn a Thesis Presented To

Phil Spector and the Wall of Sound by Steven Quinn A thesis presented to the Honors College of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the University Honors College Spring 2019 Phil Spector and the Wall of Sound by Steven Quinn APPROVED: ____________________________ Name of Project Advisor List Advisor’s Department ____________________________________ Name of Chairperson of Project Advisor List Chair’s Department ___________________________ Name of Second Reader List Second Reader’s Department ___________________________ Dr. John Vile Dean, University Honors College OR (NOT BOTH NAMES) Dr. Philip E. Phillips, Associate Dean University Honors College 2 Acknowledgments A special thank you to my thesis mentor John Hill and my second reader Dan Pfeifer for all of their help and support. I also want to say thank you to the faculty at MTSU who helped me out along the way. A thank you to my parents for all of their encouragement and everyone who helped me create this project by playing a part in it. Without your endless support and dedication to my success, this would have never been possible. Abstract Phil Spector was one of, if not the most influential producer of the 1960s and was an instrumental part in moving music in a new direction. With his “Wall of Sound” technique, he not only changed how the start of the decade sounded but influenced and changed the style of some of the most iconic groups ever to exist, including The Beach Boys and the Beatles. My research focused on how Spector developed his technique, what he did to create his iconic sound, and the impact of his influence on the music industry. -

Come Together: Fifty Years of Abbey Road Schedule and Abstracts

Come Together: Fifty Years of Abbey Road An academic conference hosted by the University of Rochester Institute for Popular Music and The Eastman School of Music September 27-29, 2019 Rochester, New York Schedule and Abstracts 2 Come Together: Fifty Years of Abbey Road An academic conference hosted by the University of Rochester Institute for Popular Music and the Eastman School of Music Abstracts Friday, September 27 9:00-10:30 Session 1 (Hatch Recital Hall), Chair: Katie Kapurch (Texas State University) Walter Everett (University of Michigan) “The Mellow Depth of Melody in Abbey Road” This talk is in response to a request from Mark Lewisohn this past summer for a comment on the abundance of melody in Abbey Road. I soon recognized this as a very useful approach to the album, which overflows with songs that relate to each other in both parallel and contrasting ways, particularly in terms of melodic content. Not only do featured lead vocal lines possess their own mature beauty, but both vocal and instrumental countermelodies—a crucial trait of middle-period Beatles—hold striking significance. I plan to discuss: how ornamentation varies repetitions, the ways in which a song's formal structure impacts melodic growth, the role of rhythm in uniting melodic motives across the LP, and the tunes within tunes in considering structural aspects of melody. Kenneth Womack (Monmouth University) “The Long One: Producing Abbey Road with George Martin and the Beatles” This paper traces the genesis of the Long One, the symphonic suite that closes Abbey Road— and, in many ways, the Beatles’ career. -

©Copyright 2010 Bradley T. Osborn

©Copyright 2010 Bradley T. Osborn Beyond Verse and Chorus: Experimental Formal Structures in Post-Millennial Rock Music Bradley T. Osborn A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2010 Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music University of Washington Graduate School This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a doctoral dissertation by Bradley T. Osborn and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Chair of the Supervisory Committee: ___________________________________________________ Áine Heneghan Reading Committee: __________________________________________________ Áine Heneghan __________________________________________________ Jonathan Bernard ___________________________________________________ John Rahn ___________________________________________________ Lawrence Starr Date: ________________________________________ In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the doctoral degree at the University of Washington, I agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of the dissertation is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for copying or reproduction of this dissertation may be referred to ProQuest Information and Learning, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346, 1-800-521-0600, to whom the author has granted “the right to reproduce and sell (a) copies of the manuscript in microform and/or (b) printed copies of the manuscript made from microform.” Signature________________________ Date____________________________ University of Washington Abstract Beyond Verse and Chorus: Expermental Formal Structures in Post-Millennial Rock Music Bradley T. Osborn Chair of Supervisory Committee: Dr. -

Everett Rock's Bands "E F"

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "E-F" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "E-F" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre 88 R P The 88 LA Rock and Pop 427 Hc M DM Wenatchee Hardcore / Metal / Death Metal $5Fine C R Tacoma Country / Rock .50Caliber Nightmare M DM Tacoma Metal / Death Metal / Freestyle 1st Street Alibi CR Al Greater Seattle Area Classic and Alternative Rock 4 outta 5 CR Seattle's Classic Rock 4&20 Blackbirds Al F R C Duvall alt-folk, rock and country 40 oz Mullet R Al Bellingham Rock / Alternative / Southern Rock 41 Miles Al R Poulsbo/Gig Harbor Alternative / Electroacoustic / Rock 44th Street Blues B Local Blues 45th parallel R Al Pr Richland Rock / Alternative / Progressive 47TH PARALLEL Al Fk R Selah Alternative / Funk / Rock 48 Degrees North Al R P Tacoma Alt Rock, Alt-Pop, Pop 4arm M T Melbourne, VIC, AU Metal / THRASH 4MORE P H Cb Seattle Pop / Club / Hip Hop 4th Avenue Al F R Everett's Melodramatic Popular Song / Alternative / Folk Rock 4th Chamber Ritual R M Puyallup rock/fun/hard rock/metal 4th Stomach Am H Bellevue Ambient Hip-Hop 5 on a String BG Vancouver BC Bluegrass 5bit Ac Seattle A Cappella 8 Second Ride C South End Country 80 Proof ALE C R Pacific Northwest Country & Rock 80's Enough NW R Seattle New Wave / Rock 80s Invasion NW P E Seattle New Wave / Pop / Electro MySpace 85th Street Big Band Sw J Seattle Swing / Jazz 8stops7 R Al M Ventura, CA Rock / Alternative Rock / Hard Rock E. -

SPA 2019 Poster 3 X 4 Alt 5

Sunday, August 4 Saturday, July 20 at 8 p.m. 12 - 5 p.m. Kids shows, family entertainment, live music, inflatables, food trucks, and more! Sunday, July 28 @ 2 p.m. Sunday, August 31 THAT 70’S BAND BELINDA CARLISLE MEADE BROTHERS OF THE GO-GO’S KINDRED SOUL at 8 p.m. 2019 STEPPINGSTONE WATERSIDE THEATRE & SUMMER EVENTS Dean Karahalis and the Mike DelGuidice Strawberry Fields Plaza productions Gin Blossoms Concert Pops celebrating the music Saturday, July 13 presents “Mamma Mia!” Saturday, July 20 Thursday, July 4 of Billy Joel Featuring former members of the hit Sunday, July 14 Remaining on the top of the hit chart for Dean Karahalis is the founder, conductor Saturday, July 6 Broadway musical “Beatlemania,” this is The hilarious story of a young woman’s almost 3 years with singles “Hey compilation of music from 1964 Jealousy,” “Allison Road,” “Until I Fall and musical director of this ensemble, Mike DelGuidice, who currently tours a search for her birth father on a Away” and “Found Out About You,” they comprised of New York’s finest musicians. through “Let It Be,” all in complete Greek island paradise includes ABBA’s with Billy Joel and his band, returns have sold over 10 million records and are costume with mop-top hair. its “Dancing Queen,” “Money, Money, with Big Shot for another great evening h one of the most in demand ‘90’s live of Billy Joel’s best. Money” and of course Mamma Mia. artists. Meade Brothers Kindred Soul That 70’s Band at 7 p.m.