Science and Poetry in the Early Reception of Aratus''phaenomena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Note on Fis 503

LECTURE NOTE ON FIS 503 FIS 503 – PRODUCTION OF OTHER MARINE PRODUCTS (2 UNITS) This Course is taught by three (3) lecturers - Dr. I.T. Omoniyi, Dr. F.I. Adeosun and Dr. A.A. Idowu The Course synopsis is further outlined on lecture basis as follows: Lectures 1 – 4: Ecology, life histories of crustaceans and aquatic molluscs Lecture 5 – 8: Culture of Shrimps, Oysters, crayfish, crabs, periwinkles and frogs Lecture 9: Culture of edible sea weeds Lecture 10 – 11: Sea and Shore farming of some products Lecture 12: Processing and preservation of marine products. ECOLOGY AND LIFE HISTORIES OF CRUSTACEANS At elementary level, crustaceans are a class of primarily aquatic arthropods. The name crustacean is derived from the Latin words ‘crusta’ meaning hard shell. The class is large (about 26,000 known species) and includes a variety of aquatic animals such as shrimps, crabs, lobsters, barnacles, water fleas etc. Some crustaceans occur in the seas and freshwaters, some are semi-terrestrial. They are mostly free-living, but few are parasitic. The common names shrimps and prawns are used interchangeably but it has now been resolved at FAO Convention to call marine and brackish water forms shrimps and freshwater forms prawns. Technically, the prawns have pleura of 2nd abdominal segment overlapping with 1st and 3rd segments ventrally. But in shrimps, the somite of 2nd abdominal segment overlaps the 3rd somite. Before commercial importance of crustaceans could be appreciated, the characteristics and the relationships need be mentioned. The main diagnostic features of the Class are: The occurrence of 2 pairs of pre-oral appendages which are antenniform and sensory in functions i.e. -

Enthymema XXIII 2019 the Technê of Aratus' Leptê Acrostich

Enthymema XXIII 2019 The Technê of Aratus’ Leptê Acrostich Jan Kwapisz University of Warsaw Abstract – This paper sets out to re-approach the famous leptê acrostich in Aratus’ Phaenomena (783-87) by confronting it with other early Greek acrostichs and the discourse of technê and sophia, which has been shown to play an important role in a gamut of Greek literary texts, including texts very much relevant for the study of Aratus’ acrostich. In particular, there is a tantalizing connection between the acrostich in Aratus’ poem that poeticized Eudoxus’ astronomical work and the so- called Ars Eudoxi, a (pseudo-)Eudoxian acrostich sphragis from a second-century BC papyrus. Keywords – Aratus; Eudoxus; Ars Eudoxi; Acrostichs; Hellenistic Poetry; Technê; Sophia. Kwapisz, Jan. “The Technê of Aratus’ Leptê Acrostich.” Enthymema, no. XXIII, 2019, pp. 374-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.13130/2037-2426/11934 https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/enthymema Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License ISSN 2037-2426 The Technê of Aratus’ Leptê Acrostich* Jan Kwapisz University of Warsaw To the memory of Cristiano Castelletti (1971-2017) Λεπτὴ μὲν καθαρή τε περὶ τρίτον ἦμαρ ἐοῦσα εὔδιός κ’ εἴη, λεπτὴ δὲ καὶ εὖ μάλ’ ἐρευθὴς πνευματίη· παχίων δὲ καὶ ἀμβλείῃσι κεραίαις 785 τέτρατον ἐκ τριτάτοιο φόως ἀμενηνὸν ἔχουσα ἠὲ νότου ἀμβλύνετ’ ἢ ὕδατος ἐγγὺς ἐόντος. (Arat. 783-87) If [the Moon is] slender and clear about the third day, she will bode fair weather; if slender and very red, wind; if the crescent is thickish, with blunted horns, having a feeble fourth-day light after the third day, either it is blurred by a southerly or because rain is in the offing. -

Celia M. Campbell CV 19/20

Celia M. Campbell Department of Classics [email protected] Emory University 221 E Candler Library Atlanta, GA 30322 EDUCATION DPhil in Latin Language & Literature November 2014 Trinity College, University of Oxford (UK) Supervisor: Professor Matthew Leigh “A Space for Song: Ovid’s Metapoetic Landscapes” MSt in Greek and/or Latin Language and Literature July 2010 Trinity College, University of Oxford (UK) Distinction “The Metamorphoses and Cyclic Epic: Ovid’s Renewal of an Epic Ideology” BA Classics, cum laude June 2009 Williams College (Massachusetts, USA) RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS Latin poetry of the late Republic and early Empire; Latin pseudepigrapha; post-Virgilian pastoral (especially Dante’s Latin eclogues); landscape and ecphrasis in Classical Literature; Senecan drama PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS/ EMPLOYMENT Emory University August 2020 Assistant Professor of Classics Florida State University August 2018-May 2020 Dean’s Post-Doctoral Scholar University of Virginia August 2017-July 2018 Assistant Professor, General Faculty Fordham University August 2016- June 2017 Adjunct Instructor New York University January 2016- June 2017 Adjunct Instructor St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford September 2015-January 2016 Lecturer St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford October 2014- July 2015 Interim Head of Classics St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford October 2013- June 2014 Career Development Fellow Trinity College, University of Oxford October 2011- October 2013 Graduate Tutor St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford October -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Mathematicians

MATHEMATICIANS [MATHEMATICIANS] Authors: Oliver Knill: 2000 Literature: Started from a list of names with birthdates grabbed from mactutor in 2000. Abbe [Abbe] Abbe Ernst (1840-1909) Abel [Abel] Abel Niels Henrik (1802-1829) Norwegian mathematician. Significant contributions to algebra and anal- ysis, in particular the study of groups and series. Famous for proving the insolubility of the quintic equation at the age of 19. AbrahamMax [AbrahamMax] Abraham Max (1875-1922) Ackermann [Ackermann] Ackermann Wilhelm (1896-1962) AdamsFrank [AdamsFrank] Adams J Frank (1930-1989) Adams [Adams] Adams John Couch (1819-1892) Adelard [Adelard] Adelard of Bath (1075-1160) Adler [Adler] Adler August (1863-1923) Adrain [Adrain] Adrain Robert (1775-1843) Aepinus [Aepinus] Aepinus Franz (1724-1802) Agnesi [Agnesi] Agnesi Maria (1718-1799) Ahlfors [Ahlfors] Ahlfors Lars (1907-1996) Finnish mathematician working in complex analysis, was also professor at Harvard from 1946, retiring in 1977. Ahlfors won both the Fields medal in 1936 and the Wolf prize in 1981. Ahmes [Ahmes] Ahmes (1680BC-1620BC) Aida [Aida] Aida Yasuaki (1747-1817) Aiken [Aiken] Aiken Howard (1900-1973) Airy [Airy] Airy George (1801-1892) Aitken [Aitken] Aitken Alec (1895-1967) Ajima [Ajima] Ajima Naonobu (1732-1798) Akhiezer [Akhiezer] Akhiezer Naum Ilich (1901-1980) Albanese [Albanese] Albanese Giacomo (1890-1948) Albert [Albert] Albert of Saxony (1316-1390) AlbertAbraham [AlbertAbraham] Albert A Adrian (1905-1972) Alberti [Alberti] Alberti Leone (1404-1472) Albertus [Albertus] Albertus Magnus -

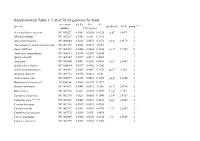

Supplementary Table 1: List of 76 Mt Genomes for Birds

Supplementary Table 1: List of 76 mt genomes for birds. accession Ka/Ks Ka Ks species speed(m/s) Ln S group * * number 13 mt genes Acrocephalus scirpaceus NC 010227 0.0464 0.0288 0.6228 6.6d 1.8871 2 Alectura lathami NC 007227 0.0343 0.032 0.9311 2 Anas platyrhynchos NC 009684 0.0252 0.0073 0.2873 18.5a 2.9178 2 Anomalopteryx didiformis (die out) NC 002779 0.0508 0.0027 0.054 1 Anser albifrons NC 004539 0.0468 0.0088 0.1856 16.1a 2.7788 2 Anseranas semipalmata NC 005933 0.0364 0.0207 0.5628 2 Apteryx haastii NC 002782 0.0599 0.0273 0.4561 1 Apus apus NC 008540 0.0401 0.0241 0.6431 10.6a 2.3609 2 Archilochus colubris NC 010094 0.0397 0.0382 0.9242 2 Ardea novaehollandiae NC 008551 0.0423 0.0067 0.1552 10.2c# 2.322 2 Arenaria interpres NC 003712 0.0378 0.0213 0.581 2 Aythya americana NC 000877 0.0309 0.0092 0.2987 24.4b 3.1946 2 Bambusicola thoracica* EU165706 0.0503 0.0144 0.2872 1 Branta canadensis NC 007011 0.0444 0.0092 0.206 16.7a 2.8154 2 Buteo buteo NC 003128 0.049 0.0167 0.3337 11.6a 2.451 2 Casuarius casuarius NC 002778 0.028 0.0085 0.3048 13.9f 2.6319 2 Cathartes aura * * * * NC 007628 0.0468 0.0239 0.4676 10.6c 2.3609 2 Ciconia boyciana NC 002196 0.0539 0.0031 0.0563 2 Ciconia ciconia NC 002197 0.0501 0.0029 0.0572 9.1d 2.2083 2 Cnemotriccus fuscatus NC 007975 0.0369 0.038 1.0476 2 Corvus frugilegus NC 002069 0.0428 0.0298 0.6526 13a 2.5649 2 Coturnix chinensis NC 004575 0.0325 0.0122 0.3762 2 Coturnix japonica NC 003408 0.0432 0.0128 0.2962 2 Cygnus columbianus NC 007691 0.0327 0.0089 0.2702 18.5a 2.9178 2 Dinornis giganteus -

Aristotle's Categories in the Early Roman Empire, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2015, in Sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr

Citation style Andrea Falcon: Rezension von: Michael J. Griffin: Aristotle's Categories in the Early Roman Empire, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2015, in sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr. 7 [15.07.2015], URL:http://www.sehepunkte.de/2015/07/27098.html First published: http://www.sehepunkte.de/2015/07/27098.html copyright This article may be downloaded and/or used within the private copying exemption. Any further use without permission of the rights owner shall be subject to legal licences (§§ 44a-63a UrhG / German Copyright Act). sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr. 7 Michael J. Griffin: Aristotle's Categories in the Early Roman Empire This is a book about the reception of Aristotle's Categories from the first century BC to the second century AD. The Categories does not appear to have circulated in the Hellenistic era. By contrast, this short but enigmatic treatise was at the center of the so-called return to Aristotle in the first century BC. The book under review tells us the story of this remarkable reversal of fortune. The main characters in this story are philosophers working in the three main philosophical traditions of post- Hellenistic philosophy. For the Peripatetic tradition, these are Andronicus of Rhodes and Boethus of Sidon. For the Academic and Platonic tradition, Eudorus of Alexandria and Lucius. For the Stoic tradition, Athenodorus and Cornutus. A supporting role is reserved to the following interpreters of the Categories : Aristo of Alexandria, Ps-Archytas, Nicostratus, Aspasius, Herminus, and Adrastus. In broad outline, the story told in the book goes as follows: Andronicus of Rhodes rescued the Categories from obscurity by deciding to place it at the beginning of his catalogue of Aristotle's writings (chapter 2). -

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

Aristotelianism in the First Century BC

CHAPTER 5 Aristotelianism in the First Century BC Andrea Falcon 1 A New Generation of Peripatetic Philosophers The division of the Peripatetic tradition into a Hellenistic and a post- Hellenistic period is not a modern invention. It is already accepted in antiquity. Aspasius speaks of an old and a new generation of Peripatetic philosophers. Among the philosophers who belong to the new generation, he singles out Andronicus of Rhodes and Boethus of Sidon.1 Strabo adopts a similar division. He too distinguishes between the older Peripatetics, who came immediately after Theophrastus, and their successors.2 He collectively describes the latter as better able to do philosophy in the manner of Aristotle (φιλοσοφεῖν καὶ ἀριστοτελίζειν). It remains unclear what Strabo means by doing philosophy in the manner of Aristotle.3 But he certainly thinks that the philosophers who belong to the new generation, and not those who belong to the old one, deserve the title of true Aristotelians. For Strabo, the event separating the old from the new Peripatos is the rediscovery and publication of Aristotle’s writings. We may want to resist Strabo’s negative characterization of the earlier Peripatetics. For Strabo, they were not able to engage in philosophy in any seri- ous way but were content to declaim general theses.4 This may be an unfair judgment, ultimately based on the anachronistic assumption that any serious philosophy requires engagement with an authoritative text.5 Still, the empha- sis that Strabo places on the rediscovery of Aristotle’s writings suggests that the latter were at the center of the critical engagement with Aristotle in the 1 Aspasius, On Aristotle’s Ethics 44.20–45.16. -

Alexander Jones Calendrica I: New Callippic Dates

ALEXANDER JONES CALENDRICA I: NEW CALLIPPIC DATES aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 129 (2000) 141–158 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 141 CALENDRICA I: NEW CALLIPPIC DATES 1. Introduction. Callippic dates are familiar to students of Greek chronology, even though up to the present they have been known to occur only in a single source, Ptolemy’s Almagest (c. A.D. 150).1 Ptolemy’s Callippic dates appear in the context of discussions of astronomical observations ranging from the early third century B.C. to the third quarter of the second century B.C. In the present article I will present new attestations of Callippic dates which extend the period of the known use of this system by almost two centuries, into the middle of the first century A.D. I also take the opportunity to attempt a fresh examination of what we can deduce about the Callippic calendar and its history, a topic that has lately been the subject of quite divergent treatments. The distinguishing mark of a Callippic date is the specification of the year by a numbered “period according to Callippus” and a year number within that period. Each Callippic period comprised 76 years, and year 1 of Callippic Period 1 began about midsummer of 330 B.C. It is an obvious, and very reasonable, supposition that this convention for counting years was instituted by Callippus, the fourth- century astronomer whose revisions of Eudoxus’ planetary theory are mentioned by Aristotle in Metaphysics Λ 1073b32–38, and who also is prominent among the authorities cited in astronomical weather calendars (parapegmata).2 The point of the cycles is that 76 years contain exactly four so-called Metonic cycles of 19 years. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Bender et al. 10.1073/pnas.0802779105 Table S1. Species names and calculated numeric values pertaining to Fig. 1 Mitochondrially Nuclear encoded Nuclear encoded Species name encoded methionine, % methionine, % methionine, corrected, % Animals Primates Cebus albifrons 6.76 Cercopithecus aethiops 6.10 Colobus guereza 6.73 Gorilla gorilla 5.46 Homo sapiens 5.49 2.14 2.64 Hylobates lar 5.33 Lemur catta 6.50 Macaca mulatta 5.96 Macaca sylvanus 5.96 Nycticebus coucang 6.07 Pan paniscus 5.46 Pan troglodytes 5.38 Papio hamadryas 5.99 Pongo pygmaeus 5.04 Tarsius bancanus 6.74 Trachypithecus obscurus 6.18 Other mammals Acinonyx jubatus 6.86 Artibeus jamaicensis 6.43 Balaena mysticetus 6.04 Balaenoptera acutorostrata 6.17 Balaenoptera borealis 5.96 Balaenoptera musculus 5.78 Balaenoptera physalus 6.02 Berardius bairdii 6.01 Bos grunniens 7.04 Bos taurus 6.88 2.26 2.70 Canis familiaris 6.54 Capra hircus 6.84 Cavia porcellus 6.41 Ceratotherium simum 6.06 Choloepus didactylus 6.23 Crocidura russula 6.17 Dasypus novemcinctus 7.05 Didelphis virginiana 6.79 Dugong dugon 6.15 Echinops telfairi 6.32 Echinosorex gymnura 6.86 Elephas maximus 6.84 Equus asinus 6.01 Equus caballus 6.07 Erinaceus europaeus 7.34 Eschrichtius robustus 6.15 Eumetopias jubatus 6.77 Felis catus 6.62 Halichoerus grypus 6.46 Hemiechinus auritus 6.83 Herpestes javanicus 6.70 Hippopotamus amphibius 6.50 Hyperoodon ampullatus 6.04 Inia geoffrensis 6.20 Bender et al. www.pnas.org/cgi/content/short/0802779105 1of10 Mitochondrially Nuclear encoded Nuclear encoded Species -

The Magic of the Atwood Sphere

The magic of the Atwood Sphere Exactly a century ago, on June Dr. Jean-Michel Faidit 5, 1913, a “celestial sphere demon- Astronomical Society of France stration” by Professor Wallace W. Montpellier, France Atwood thrilled the populace of [email protected] Chicago. This machine, built to ac- commodate a dozen spectators, took up a concept popular in the eigh- teenth century: that of turning stel- lariums. The impact was consider- able. It sparked the genesis of modern planetariums, leading 10 years lat- er to an invention by Bauersfeld, engineer of the Zeiss Company, the Deutsche Museum in Munich. Since ancient times, mankind has sought to represent the sky and the stars. Two trends emerged. First, stars and constellations were easy, especially drawn on maps or globes. This was the case, for example, in Egypt with the Zodiac of Dendera or in the Greco-Ro- man world with the statue of Atlas support- ing the sky, like that of the Farnese Atlas at the National Archaeological Museum of Na- ples. But things were more complicated when it came to include the sun, moon, planets, and their apparent motions. Ingenious mecha- nisms were developed early as the Antiky- thera mechanism, found at the bottom of the Aegean Sea in 1900 and currently an exhibi- tion until July at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in Paris. During two millennia, the human mind and ingenuity worked constantly develop- ing and combining these two approaches us- ing a variety of media: astrolabes, quadrants, armillary spheres, astronomical clocks, co- pernican orreries and celestial globes, cul- minating with the famous Coronelli globes offered to Louis XIV.