UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zhang Yimou Interviews Edited by Frances Gateward

ZHANG YIMOU INTERVIEWS EDITED BY FRANCES GATEWARD Discussing Red Sorghum JIAO XIONGPING/1988 Winning Winning Credit for My Grandpa Could you discuss how you chose the novel for Red Sorghum? I didn't know Mo Yan; I first read his novel, Red Sorghum, really liked it, and then gave him a phone call. Mo Yan suggested that we meet once. It was April and I was still filming Old Well, but I rushed to Shandong-I was tanned very dark then and went just wearing tattered clothes. I entered the courtyard early in the morning and shouted at the top of my voice, "Mo Yan! Mo Yan!" A door on the second floor suddenly opened and a head peered out: "Zhang Yimou?" I was dark then, having just come back from living in the countryside; Mo Yan took one look at me and immediately liked me-people have told me that he said Yimou wasn't too bad, that I was just like the work unit leader in his village. I later found out that this is his highest standard for judging people-when he says someone isn't too bad, that someone is just like this village work unit leader. Mo Yan's fiction exudes a supernatural quality "cobblestones are ice-cold, the air reeks of blood, and my grandma's voice reverberates over the sorghum fields." How was I to film this? There was no way I could shoot empty scenes of the sorghum fields, right? I said to Mo Yan, we can't skip any steps, so why don't you and Chen Jianyu first write a literary script. -

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

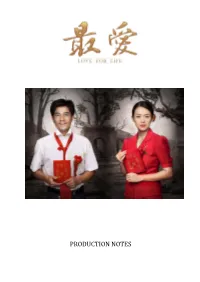

Zhang Ziyi and Aaron Kwok

PRODUCTION NOTES Set in a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, LOVE FOR LIFE is the story of De Yi and Qin Qin, two victims faced with the grim reality of impending death, who unexpectedly fall in love and risk everything to pursue a last chance at happiness before it’s too late. SYNOPSIS In a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, the Zhao’s are a family caught in the middle. Qi Quan is the savvy elder son who first lured neighbors to give blood with promises of fast money while Grandpa, desperate to make amends for the damage caused by his family, turns the local school into a home where he can care for the sick. Among the patients is his second son De Yi, who confronts impending death with anger and recklessness. At the school, De Yi meets the beautiful Qin Qin, the new wife of his cousin and a recent victim of the virus. Emotionally deserted by their respective spouses, De Yi and Qin Qin are drawn to each other by the shared disappointment and fear of their fate. With nothing to look forward to, De Yi capriciously suggests becoming lovers but as they begin their secret affair, they are unprepared for the real love that grows between them. De Yi and Qin Qin’s dream of being together as man and wife, to love each other legitimately and freely, is jeopardized when the villagers discover their adultery. With their time slipping away, they must decide if they will surrender everything to pursue one chance at happiness before it’s too late. -

Ethical Transformations in Yan's 陆犯焉识 (The Criminal Lu Yanshi)

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 17 (2015) Issue 5 Article 11 Ethical Transformations in Yan's ???? (The Criminal Lu Yanshi) Weihong Zhu Central China Normal University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Chinese Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Zhu, Weihong. "Ethical Transformations in Yan's ???? (The Criminal Lu Yanshi)." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 17.5 (2015): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2759> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 189 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

Rebuilding the Ancestral Temple and Hosting Daluo Heaven and Earth Prayer and Enlightenment Ceremony

Cultural and Religious Studies, July 2020, Vol. 8, No. 7, 386-402 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2020.07.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING Rebuilding the Ancestral Temple and Hosting Daluo Heaven and Earth Prayer and Enlightenment Ceremony Wu Hui-Chiao Ming Chuan University, Taiwan Kuo, Yeh-Tzu founded Taiwan’s Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple in 1970. She organized more than 200 worshipers as a group named “Taiwan Tsu Huei Temple Queen Mother of the West Delegation to China to Worship at the Ancestral Temples” in 1990. At that time, the temple building of the Queen Mother Palace in Huishan of Gansu Province was in disrepair, and Temple Master Kuo, Yeh-Tzu made a vow to rebuild it. Rebuilding the ancestral temple began in 1992 and was completed in 1994. It was the first case of a Taiwan temple financing the rebuilding of a far-away Queen Mother Palace with its own donations. In addition, Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple celebrated its 45th anniversary and hosted Yiwei Yuanheng Lizhen Daluo Tiandi Qingjiao (Momentous and Fortuitous Heaven and Earth Prayer Ceremony) in 2015. This is the most important and the grandest blessing ceremony of Taoism, a rare event for Taoism locally and abroad during this century. Those sacred rituals were replete with unprecedented grand wishes to propagate the belief in Queen Mother of the West. Stopping at nothing, Queen Mother’s love never ceases. Keywords: Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple, Temple Master Kuo, Yeh-Tzu, Golden Mother of the Jade Pond, Daluo Tiandi Qingjiao (Daluo Heaven and Earth Prayer Ceremony) Introduction The main god, Golden Mother of the Jade Pond (Golden Mother), enshrined in Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple, is the same as the Queen Mother of the West, the highest goddess of Taoism. -

Problematizing the Stereotype of the Prostitutes As Seen in Geling Yan's the Flowers of War

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PROBLEMATIZING THE STEREOTYPE OF THE PROSTITUTES AS SEEN IN GELING YAN'S THE FLOWERS OF WAR AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By Florina Leonora Tyana Student Number: 114214009 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2018 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PROBLEMATIZING THE STEREOTYPE OF THE PROSTITUTES AS SEEN IN GELING YAN'S THE FLOWERS OF WAR AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By Florina Leonora Tyana Student Number: 114214009 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2018 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI TIME IS PRECIOUS vii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI Dedicated to My beloved parents, My little Brother, And ‘you know who’ viii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In this part, I would like to send my love and thank them for this part of journey in my life. First and foremost, I would love to thank Jesus Christ, because HE listen to all my prayer and my parent prayer‟s. To my thesis advisor, Elisa Wardhani S.S, M.Hum whose is always be patience to correct my thesis and for her big help in guiding me during the process of finishing this thesis. I also would like to thank Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka, M.Hum for his guidance and support. -

The Rhesus Factor and Disease Prevention

THE RHESUS FACTOR AND DISEASE PREVENTION The transcript of a Witness Seminar held by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, London, on 3 June 2003 Edited by D T Zallen, D A Christie and E M Tansey Volume 22 2004 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 2004 First published by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2004 The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at University College London is funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 0 85484 099 1 Histmed logo images courtesy Wellcome Library, London. Design and production: Julie Wood at Shift Key Design 020 7241 3704 All volumes are freely available online at: www.history.qmul.ac.uk/research/modbiomed/wellcome_witnesses/ Please cite as : Zallen D T, Christie D A, Tansey E M. (eds) (2004) The Rhesus Factor and Disease Prevention. Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, vol. 22. London: Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL. CONTENTS Illustrations and credits v Witness Seminars: Meetings and publications;Acknowledgements vii E M Tansey and D A Christie Introduction Doris T Zallen xix Transcript Edited by D T Zallen, D A Christie and E M Tansey 1 References 61 Biographical notes 75 Glossary 85 Index 89 Key to cover photographs ILLUSTRATIONS AND CREDITS Figure 1 John Walker-Smith performs an exchange transfusion on a newborn with haemolytic disease. Photograph provided by Professor John Walker-Smith. Reproduced with permission of Memoir Club. 13 Figure 2 Radiograph taken on day after amniocentesis for bilirubin assessment and followed by contrast (1975). -

Cosmopolitan Cinema: Cross-Cultural Encounters in East Asian Film

Chan, Felicia. "Index." Cosmopolitan Cinema: Cross-Cultural Encounters in East Asian Film. London • New York: I.B.Tauris, 2017. 193–204. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 22:31 UTC. Copyright © Felicia Chan 2017. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 193 Index Note: Page numbers in italics refer to images. 2.28 incident, 48 audiences, 94 – 5 , 122 – 3 , 145 15 , 110 , 111 Austin, J. L., 70 24 City , 59 – 68 Austin, Th omas, 60 – 1 , 63 – 4 2046 , 30 , 33 , 36 , 50 auteur cinema, 8 , 40 – 1 , 111 autoethnographer- performer, 133 Abbas, Ackbar, 30 a w a r d s , 2 5 – 6 a ff ect, 17 , 94 , 95 – 6 , 97 , 101 , 118 a ff ective encounter, 94 Bachelard, Gaston, 104 , 105 a ffi rmative criticality, 142 Baecker, Angie, 124 , 139 Aft er Chinatown , 130 – 1 Bal, Le , 26 Ahmad, Yasmin, 111 Balfour, Ian, 40 , 52 Ahmed, Sara, 123 , 136 banned fi lms, 58 – 9 , 110 Allen, Richard, 120 – 1 Bauman, Zygmunt, 7 – 8 , 9 Allen, Woody, 10 Be With Me , 2 5 – 6 Almodóvar, Pedro, 39 Béhar, Henri, 39 Always in My Heart / Kimi no Behind the Forbidden City , 110 nawa , 81 , 83 ‘Bengawan Solo’, 32 Ampo demonstrations, 83 Benjamin, Walter, 10 , 133 Andersen, Joseph, 22 – 3 benshi narrators, 21 – 4 Anderson, Benedict, 100 Bergfelder, Tim, 11 Anderson, Kay, 130 Bergman, Ingrid, 73 , 75 , 125 animation Berlant, Laurent, 109 , -

1St China Onscreen Biennial

2012 1st China Onscreen Biennial LOS ANGELES 10.13 ~ 10.31 WASHINGTON, DC 10.26 ~ 11.11 Presented by CONTENTS Welcome 2 UCLA Confucius Institute in partnership with Features 4 Los Angeles 1st China Onscreen UCLA Film & Television Archive All Apologies Biennial Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Are We Really So Far from the Madhouse? Film at REDCAT Pomona College 2012 Beijing Flickers — Pop-Up Photography Exhibition and Film Seeding cross-cultural The Cremator dialogue through the The Ditch art of film Double Xposure Washington, DC Feng Shui Freer and Sackler Galleries of the Smithsonian Institution Confucius Institute at George Mason University Lacuna — Opening Night Confucius Institute at the University of Maryland The Monkey King: Uproar in Heaven 3D Confucius Institute Painted Skin: The Resurrection at Mason 乔治梅森大学 孔子学院 Sauna on Moon Three Sisters The 2012 inaugural COB has been made possible with Shorts 17 generous support from the following Program Sponsors Stephen Lesser The People’s Secretary UCLA Center for Chinese Studies Shanghai Strangers — Opening Night UCLA Center for Global Management (CGM) UCLA Center for Management of Enterprise in Media, Entertainment and Sports (MEMES) Some Actions Which Haven’t Been Defined Yet in the Revolution Shanghai Jiao Tong University Chinatown Business Improvement District Mandarin Plaza Panel Discussion 18 Lois Lambert of the Lois Lambert Gallery Film As Culture | Culture in Film Queer China Onscreen 19 Our Story: 10 Years of Guerrilla Warfare of the Beijing Queer Film Festival and -

In the Mood for Love, Suzhou He Film Studio, Bar : Shanghai Tongzhi Community Junfeng Ding Iowa State University

Masthead Logo Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2005 In the mood for love, Suzhou He Film Studio, Bar : Shanghai Tongzhi community Junfeng Ding Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Ding, Junfeng, "In the mood for love, Suzhou He Film Studio, Bar : Shanghai Tongzhi community" (2005). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18940. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18940 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In the Mood for Love - Suzhou He Film Studio, Bar I Shanghai T ongzhi community by Junfeng Qeff) Ding A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE Major: Architecture Program of Study Committee: Timothy Hickman, Major Professor Clare Robinson, Major Professor Julia Badenhope Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2005 Copyright ©Junf eng Qeff) Ding. , 2005. All. rights reserved. II Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Junfeng Qeff) Ding has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy Ill Acknowledgements The moment of finishing my thesis for the professional M.Arch degree is the moment I studying for the post ~ professional M.Des degree in Graduate School of Design (GSD), Harvard University. -

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

Film and the Chinese Medical Humanities

5 The fever with no name Genre-blending responses to the HIV-tainted blood scandal in 1990s China Marta Hanson Among the many responses to HIV/AIDS in modern China – medical, political, economic, sociological, national, and international – the cultural responses have been considerably powerful. In the past ten years, artists have written novels, produced documentaries, and even made a major feature-length film in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China.1 One of the best-known critical novelists in China today, Yan Lianke 阎连科 (b. 1958), wrote the novel Dream of Ding Village (丁庄梦, copyright 2005; Hong Kong 2006; English translation 2009) as a scath- ing critique of how the Chinese government both contributed to and poorly han- dled the HIV/AIDS crisis in his native Henan province. He interviewed survivors, physicians, and even blood merchants who experienced first-hand the HIV/AIDS ‘tainted blood’ scandal in rural Henan of the 1990s giving the novel authenticity, depth, and heft. Although Yan chose a child-ghost narrator, the Dream is clearly a realistic novel. After signing a contract with Shanghai Arts Press he promised to donate 50,000 yuan of royalties to Xinzhuang village where he researched the AIDS epidemic in rural Henan, further blurring the fiction-reality line. The Chi- nese government censors responded by banning the Dream in Mainland China (Wang 2014: 151). Even before director Gu Changwei 顾长卫 (b. 1957) began making a feature film based on Yan’s banned book, he and his wife Jiang Wenli 蒋雯丽 (b. 1969) sought to work with ordinary people living with HIV/AIDS as part of the process of making the film.