The Art of Defence on Foot with the Broad Sword and Sabre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Kids, Their Swords, and Surviving It All with Your Sanity Intact

The PARENTS’ FENCING SURVIVAL GUIDE 2015 EDITION This is a bit of a read! It won’t send you to sleep but best to dip in as required Use Ctrl+click on a content heading to jump to that section Contents Why Fencing? ........................................................................................................................... 3 How Will Fencing Benefit My Child? ......................................................................................... 4 Fencing: So Many Flavours to Choose From ............................................................................ 4 Is it Safe? (We are talking about sword fighting) ....................................................................... 5 Right-of-What? A List of Important Terms ................................................................................. 6 Overview of the Three Weapons .............................................................................................. 9 Getting Started: Finding Classes ............................................................................................ 12 The Training Diary .................................................................................................................. 12 Getting Started: Basic Skills and Gear .................................................................................... 13 Basic Equipment: A Little more Detail ..................................................................................... 14 Note: Blade Sizes – 5, 3, 2, 0, What? .................................................................................... -

The European Bronze Age Sword……………………………………………….21

48-JLS-0069 The Virtual Armory Interactive Qualifying Project Proposal Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation by _____________________________ ____________________________ Patrick Feeney Jennifer Baulier _____________________________ Ian Fite February 18th 2013 Professor Jeffrey L. Forgeng. Major Advisor Keywords: Higgins Armory, Arms and Armor, QR Code 1 Abstract This project explored the potential of QR technology to provide interactive experiences at museums. The team developed content for selected objects at the Higgins Armory Museum. QR codes installed next to these artifacts allow visitors to access a variety of minigames and fact pages using their mobile devices. Facts for the object are selected randomly from a pool, making the experience different each time the code is scanned, and the pool adapts based on artifacts visited, personalizing the experience. 2 Contents Contents........................................................................................................................... 3 Figures..............................................................................................................................6 Introduction ……………………………………………......................................................... 9 Double Edged Swords In Europe………………………………………………………...21 The European Bronze Age Sword……………………………………………….21 Ancient edged weapons prior to the Bronze Age………………………..21 Uses of European Bronze Age swords, general trends, and common innovations -

The Seven Sabre Guards for a Right Handed Fencer

The Seven Sabre Guards for a Right handed fencer. st “Prime” 1 Guard or Parry (Hand in Pronation “Quinte” 5th Guard or parry (Hand in Pronation) “Seconde” 2nd Guard or Parry (Hand in Pronation) “Sixte” 6th Guard or Parry (Hand in half Supination) “Tierce” 3rd Guard or Parry (Hand in Pronation) th “Offensive Defensive position” 7 Guard of Parry (Hand in half Pronation) Supination: Means knuckles of the sword hand pointing down. Half Pronation: Means knuckles pointing towards the sword arm side of the body with the thumb on top of the sword handle. Pronation: Means knuckles of the sword hand pointing th “Quarte” 4 Guard or Parry (hand in Half Pronation) upwards. Copyright © 2000 M.J. Dennis Below is a diagram showing where the Six fencing positions for Sabre are assuming the fencer is right handed (sword arm indicated) the Target has been Quartered to show the High and Low line Guards (note the offensive/defensive position is an adaptation of tierce and quarte). Sixte: (Supinated) To protect the head Head Quinte: (Pronation) To protect the head Cheek Cheek High Outside High Inside Tierce: (½ Pronation) to Prime: (Pronation) to protect the sword arm, protect the inside chest, and chest, and cheek. belly. Seconde: (Pronation) Fencers to protect the belly and Quarte: (½ Pronation) To Sword-arm flank protect chest and cheek Flank Low Outside Low Inside Belly The Sabre target is everything above the waist. This includes the arms, hands and head. Copyright © 2000 M.J. Dennis Fencing Lines. Fencing lines can cause a great deal of confusion, so for ease I shall divide them into four separate categories. -

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Turner, Anthony N. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5121-432X (2016) Physical preparation for fencing: tailoring exercise prescription and training load to the physiological and biomechanical demands of competition. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/18942/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Swordsmanship and Sabre in Fribourg

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Hands-on section, articles 103 Hands-on section, articles Sweat and Blood: Swordsmanship and sabre in Fribourg Mathijs Roelofsen, PhD Student, University of Bern [email protected], and Dimitri Zufferey, Independant Researcher, GAFSchola Fribourg, [email protected] Abstract – Following a long mercenary tradition, Switzerland had to build in the 19th century its own military tradition. In Cantons that have provided many officers and soldiers in the European Foreign Service, the French military influence remained strong. This article aims to analyze the development of sabre fencing in the canton of Fribourg (and its French influence) through the manuals of a former mercenary (Joseph Bonivini), a fencing master in the federal troops (Joseph Tinguely), and an officer who became later a gymnastics teacher (Léon Galley). These fencing manuals all address the recourse to fencing as physical training and gymnastic exercise, and not just as a combat system in a warlike context. Keywords – Sabre, Fribourg, Valais, Switzerland, fencing, contre-pointe, bayonet I. INTRODUCTION In military history, the Swiss are known for having offered military service as mercenaries over a long time period. In the 19th century, this system was however progressively abandoned, while the country was creating its own national army from the local militias. The history of 19th century martial practices in Switzerland did not yet get much attention from historians and other researchers. This short essay is thus a first attempt to set some elements about fencing in Switzerland at that time, focusing on some fencing masters from one Swiss Canton (Fribourg) through biographical elements and fencing manuals. -

Fencers Club Pro Shop Catalog

Fencers Club is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization dedicated to the pursuit of excellence through the sport of fencing. We actively support a culture of sharing by performing community services that extend beyond fencing. Fencers Club Pro Shop Catalog As part of the Fencers Club Member Services, the Pro Shop provides our members the services and fencing gear needed for training and competitions. The prices listed are the online prices from our vendors and are subject to change. Net proceeds from the Pro Shop go to the Fencers Club Scholarship Fund to support our members. The catalog items are listed alphabetically and sorted by beginner, intermediate and advance. Page 2: Bags, Blades Page 3: Complete Weapons, FC Items, Gloves Page 4: Jackets, Knickers, Lames Page 5: Masks Page 6: Plastron/Chest Protectors, Shoes & Socks, Misc. Equipment Page 7: Order Form Order by email to [email protected] or stop by the Pro Shop. For your convenience, an order form is enclosed. Feel free to send a photo or scanned copy of the form and let us know when you would like to pick up the items. Thank you all for being the best part of Fencers Club. Bags AF Junior Bag with Wheels - $95 AF Multi-Weapon Bag - $38 Hard Blade Cover - $5 FC Stenciled Single Weapon Bag - $12 Soft Blade Cover - $4 FC Olympic Bag Limited Edition - $100 Leon Paul Team Bag (includes shipping) - $321 Leon Paul Freeroller Bag - $208 Radical Fencing Liberty Bag - $395 Radical Fencing Strip Bag (includes complimentary stenciling) - $100 Radical Fencing Sorcerer Bag - $148 Radical -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

Swords and Sabers During the Early Islamic Period

Gladius XXI, 2001, pp. 193-220 SWORDS AND SABERS DURING THE EARLY ISLAMIC PERIOD POR DAVID ALEXANDER ABSTRACT - RESUMEN The present article offers a discussion on early swords and sabers during the Early Islamic Period, from the Topkapí Sarayi collection to written, iconographic and archeological sources. El presente artículo trata las espadas y sables utilizados en los primeros tiempos del Islam a partir de la co- lección del Topkapí Sarayi y de las fuentes escritas, iconográficas y arqueológicas. KEY WORDS - PALABRAS CLAVE Swords. Sabers. Islam. Topkapí Sarayi, Istambul. Espadas. Sables. Islam. Topkapí Sarayi. Estambul. SWORDS DURING THE EARLY ISLAMIC PERIOD The recent discovery in Spain of a ninth century sword represents a remarkable advance in our knowledge of early Islamic swords. This archaeological find is discussed in detail by Alberto Canto in this volume, the present article offers a discussion of early swords and sa- bers in general. Reference is also made to the so called saif badaw^ used in the investiture of ¿Abbasid caliphs under the Mamluks; and to the origins of the saber which represents an eastern influence on the Islamic world A sword is a weapon with a straight double-edged blade, generally pointed at its tip, and can be used for both cutting and thrusting; the hilt of a sword is generally symmetrical in form. A s ab er ca n b e de fi n ed a s a we a p on wi th a s i ng le - ed ge d b la de , s omet i me s s ha rp en e d a dd it io n al ly al on g t he l o we r pa r t of it s ba c k ed g e, d es i gn ed fo r cu t ti ng an d sl a sh in g .1 Al th ou g h s ab er s a re u s ua ll y c ur ve d , ea rl i er e x ampl es ar e l es s so an d s ome ar e v ir t ua ll y s tr ai g ht . -

7Th Sea School Handbook

7th Sea School Handbook by Stephen D'Angelo ([email protected]) with additional content from Andy Aiken updated January 8, 2004 Key to Sourcebooks: AH = Arrow of Heaven AV = Avalon CA = Castille CE = Crescent Empire CJE = Cathay, Jewel of the East CM = 7th Sea Compendium CN# = Crow's Nest (issue #) CP = Church of the Prophets DK = Die Kreuzritter FR = Freiburg (box set) EN = Eisen ES = Explorer’s Society GM = GM's Guide IC = Invisible College IG = Islands of Gold KM = Knights and Musketeers LF = Lady's Favor (GM's Screen) LV = Los Vagos MO = Montaigne MR = Montaigne Revolution NM# = NOM (issue #) PG = Player's Guide PN = Pirate Nations RC = Knights of the Rose & Cross RI = Rilasciare SBN = Sidhe Book of Nightmares SD = Sophia's Daughters SF = Scoundrel's Folly SG = Swordsman’s Guild SH = Strongholds and Hideouts US = Ussura VK = Villains Kit VO = Vodacce VV = Vendel / Vesten WOB = Waves of Blood Overview of Schools A school represents a special area of study, usually in combat or weapons. Each school includes 4 or more knacks. These knacks are treated as advanced knacks. As with other knacks, none of these knacks may be increased above 6 at hero creation. You start at Apprentice level. To achieve Journeyman, you must have rank 4 in at least 4 knacks. To achieve Master, you must have rank 5 in at least 4 knacks. Knacks are not unique per school, so if you have more than one school with the same knack, those knacks are considered the same knack in all ways. Schools Combat schools provide your character with expert training in a combat (usually a weapon such as a sword). -

COLD ARMS Zoran Markov Dragutin Petrović

COLD ARMS Zoran Markov Dragutin Petrović MUZEUL BANATULUI TIMIŞOARA 2012 PREFACE Authors of the catalog and exhibition: Zoran Markov, Curator, Banat Museum of Timisoara Dragutin Petrović, Museum - Consultant, The City Museum of Vršac Associates at the exhibition: Vesna Stankov, Etnologist, Senior Curator Dragana Lepir, Historian Reviewer: “Regional Centre for the Heritage of Banat — Concordia” is set adopted a draft strategy for long-term research, protection and pro- Eng. Branko Bogdanović up with funds provided by the EU and the Municipality of Vršac, motion of the cultural heritage of Banat, where Banat means a ge- Catalog design: as a cross-border cooperation project between the City Museum ographical region, which politically belongs to Romania, Hungary Javor Rašajski of Vršac (CMV) and Banat Museum in Timisoara (MBT). In im- and Serbia. Photos: plementation of this project, the reconstruction of the building of All the parts of the Banat region have been inextricably linked Milan Šepecan Concordia has a fundamental role. It will house the Regional Centre by cultural relations since the earliest prehistoric times. Owing to Ivan Kalnak and also be a place for the permanent museum exhibition. its specific geographical position, distinctive features and the criss- Technical editor: The main objective of establishing the Regional Centre in crossing rivers Tisza, Tamis and Karas, as the ways used for spread- Ivan Kalnak Concordia is cross-border cooperation between all institutions of ing influence by a number of different cultures, identified in archae- COLD ARMS culture and science in the task of production of a strategic plan ological research, the area of Banat represents today an inexhaust- and creation of best conditions for the preservation and presenta- ible source of information about cultural and historic ties. -

Swordplay Through the Ages Daniel David Harty Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester Polytechnic Institute Digital WPI Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) Interactive Qualifying Projects April 2008 Swordplay Through The Ages Daniel David Harty Worcester Polytechnic Institute Drew Sansevero Worcester Polytechnic Institute Jordan H. Bentley Worcester Polytechnic Institute Timothy J. Mulhern Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all Repository Citation Harty, D. D., Sansevero, D., Bentley, J. H., & Mulhern, T. J. (2008). Swordplay Through The Ages. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/3117 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Interactive Qualifying Projects at Digital WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) by an authorized administrator of Digital WPI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IQP 48-JLS-0059 SWORDPLAY THROUGH THE AGES Interactive Qualifying Project Proposal Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation by __ __________ ______ _ _________ Jordan Bentley Daniel Harty _____ ________ ____ ________ Timothy Mulhern Drew Sansevero Date: 5/2/2008 _______________________________ Professor Jeffrey L. Forgeng. Major Advisor Keywords: 1. Swordplay 2. Historical Documentary Video 3. Higgins Armory 1 Contents _______________________________ ........................................................................................0 Abstract: .....................................................................................................................................2 -

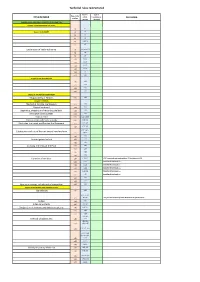

Technical Rules Restructured

Technical rules restructured Former Type of New article article inconsistency TITLE IN INDEX number Correction number detected GENERAL RULES AND RULES COMMON TO ALL WEAPONS Chapter 1: APPLICATION OF THE RULES t.1 t.1 Chapter 2: GLOSSARY t.2 t.2 t.3 t.3 t.4 t.4 t.5 t.107.1 t.6 t.5 Explanation of technical terms t.7 footnote (1) t.8 t.6 t.9 t.7 t.10 t.8.1 t.11 t.8.2 t.12 t.8.3 t.13 t.8.4 t.14 t.9 t.15 t.10 Chapter 3: THE FIELD OF PLAY t.16 t.11 t.17 t.12 t.18 t.13 t.19 t.14 Chapter 4: THE FENCER'S EQUIPMENT Responsibility of Fencers t.20 t.15 Chapter 5: FENCING Method of Holding the Weapon t.21 t.16 Coming on guard t.22 t.17 Beginning, stopping and restarting the bout t.23 t.18 Fencing at close quarters t.24 t.19 Corps a corps t.25 t.20, t.63.1 Corps a corps and fleche attacks t.26 t.63.3-4 Displacing the target and Passing the Opponent t.27 t.21.1/2 t.28 t.21.3-5 Substitution and use of the non-sword hand and arm t.22.1 & 3, t.29 t.72.2 t.30 t.23 Ground gained or lost t.31 t.24 t.32 t.25 Crossing the limits of the Piste t.33 t.26 t.34 t.27 t.35 t.28 t.36 t.29 Duration of the bout t.37 t.30,1-2 t.30.3 removed and replaced by o.17 that became t.38 t.38 o.17 transfer from book o.