The Neapolitan School of Fencing: Its Origins and Early Characteristics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Novel Lunge Biomechanics in Modern Sabre Fencing

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Engineering 112 ( 2015 ) 473 – 478 7th Asia-Pacific Congress on Sports Technology, APCST 2015 Novel Lunge Biomechanics in Modern Sabre Fencing Kevin C. Moorea; Frances M. E. Chowb; John Y. H. Chowb a Re-embody,b 1300 Asia Standard Tower, 59-65 Queen’s Road Central Hong Kong SAR Sydney Sabre, Level 1, 112-116 Parramatta Road Stanmore NSW 2048, Australia Abstract Sabre is one of the three disciplines in the sport of fencing, characterised by the use of a lightweight cutting weapon to score hits on an opponent while maneuvering for position with rapid and dynamic footwork. One of the main techniques is the lunge: an explosive extension of the fencer’s body propelled by the non-dominant (ND) leg in which the dominant (D) leg is kicked forward. The lunge provides both power and range (up to 3m) to the fencer and helps accelerate the sword for a rapid strike. Classical fencing lunges differ in style but share a common mechanism: a forward leap originating in the ND leg that powers rotation in a highly mobile thoracic cage. A new generation of fencers has begun to deviate from the classical lunge mechanism in recent years with a ND leg adopting a rigid momentum-conserving structure. This constant ND knee extension yields a constant rotational acceleration of the pelvis toward the dominant side and emphases scapular rotation to transfer power to the sword arm compared to thoracic rotation in classical lunges. We hypothesized that the new lunge mechanism delivers greater power, efficiency, range, and acceleration than the classical lunge. -

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Turner, Anthony N. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5121-432X (2016) Physical preparation for fencing: tailoring exercise prescription and training load to the physiological and biomechanical demands of competition. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/18942/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Downloaded and Shared for Private Use Only – Republication, in Part Or in Whole, in Print Or Online, Is Expressly Forbidden Without the Written Consent of the Author

The International Armizare Society Presents: Beginning Armizare An Introduction to Medieval Swordsmanship Gregory D. Mele © 2001 - 2016 Beginning Armizare: An Introduction to Medieval Swordsmanship Copyright Notice: © 2014 Gregory D. Mele, All Rights Reserved. This document may be downloaded and shared for private use only – republication, in part or in whole, in print or online, is expressly forbidden without the written consent of the author. ©2001-2016 Gregory D. Mele Page 2 Beginning Armizare: An Introduction to Medieval Swordsmanship TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 4 Introduction: The Medieval Art of Arms 5 I. Spada a Dui Mani: The Longsword 7 II. Stance and Footwork 9 III. Poste: The Guards of the Longsword 14 IV. Learning to Cut with the Longsword 17 V. Defending with the Fendente 23 VI. Complex Blade Actions 25 VII. Parrata e Risposta 25 Appendix A: Glossary 28 Appendix B: Bibliography 30 Appendix C: Armizare Introductory Class Lesson Plan 31 ©2001-2016 Gregory D. Mele Page 3 Beginning Armizare: An Introduction to Medieval Swordsmanship FOREWORD The following document was originally developed as a study guide and training companion for students in the popular "Taste of the Knightly Arts" course taught by the Chicago Swordplay Guild. It has been slightly revised, complete with the 12 class outline used in that course in order to assist new teachers, small study groups or independent students looking for a way to begin their study of armizare. Readers should note that by no means is this a complete curriculum. There is none of the detailed discussion of body mechanics, weight distribution or cutting mechanics that occurs during classroom instruction, nor an explanation of the number of paired exercises that are used to develop student's basic skills, outside of the paired techniques, or "set-plays," themselves. -

7Th Sea School Handbook

7th Sea School Handbook by Stephen D'Angelo ([email protected]) with additional content from Andy Aiken updated January 8, 2004 Key to Sourcebooks: AH = Arrow of Heaven AV = Avalon CA = Castille CE = Crescent Empire CJE = Cathay, Jewel of the East CM = 7th Sea Compendium CN# = Crow's Nest (issue #) CP = Church of the Prophets DK = Die Kreuzritter FR = Freiburg (box set) EN = Eisen ES = Explorer’s Society GM = GM's Guide IC = Invisible College IG = Islands of Gold KM = Knights and Musketeers LF = Lady's Favor (GM's Screen) LV = Los Vagos MO = Montaigne MR = Montaigne Revolution NM# = NOM (issue #) PG = Player's Guide PN = Pirate Nations RC = Knights of the Rose & Cross RI = Rilasciare SBN = Sidhe Book of Nightmares SD = Sophia's Daughters SF = Scoundrel's Folly SG = Swordsman’s Guild SH = Strongholds and Hideouts US = Ussura VK = Villains Kit VO = Vodacce VV = Vendel / Vesten WOB = Waves of Blood Overview of Schools A school represents a special area of study, usually in combat or weapons. Each school includes 4 or more knacks. These knacks are treated as advanced knacks. As with other knacks, none of these knacks may be increased above 6 at hero creation. You start at Apprentice level. To achieve Journeyman, you must have rank 4 in at least 4 knacks. To achieve Master, you must have rank 5 in at least 4 knacks. Knacks are not unique per school, so if you have more than one school with the same knack, those knacks are considered the same knack in all ways. Schools Combat schools provide your character with expert training in a combat (usually a weapon such as a sword). -

Fencing: a Modern Sport

Fencing: A Modern Sport (Recreated from the document that formerly resided on the USFA website [and we would link to it if it was still available on the USFA site!]) The sport of fencing is fast and athletic, a far cry from the choreographed bouts you see on film or on the stage. Instead of swinging from a chandelier or leaping from balconies, you will see two fencers performing an intense dance on a 6-feet by 44-feet strip. The movement is so fast the touches are scored electrically – a lot more like Star Wars than Errol Flynn. The Bout Competitors win a fencing bout (what an individual “game” is called) by being the first to score 15 points (in direct elimination play) or 5 points (in preliminary pool play) against their opponent, or by having a higher score than their opponent when the time limit expires. Each time a fencer lands a valid hit – a touch - on their opponent, they receive one point. The time limit for direct elimination matches is nine minutes - three three-minute periods with a one minute break between each. Fencers are penalized for crossing the lateral boundaries of the strip, while retreating off the rear limit of their side results in a touch awarded to their opponent. Team matches feature three fencers squaring off against another team of three in a "relay" format. Each team member fences every member of the opposing team in sequence over 9 rounds until one team reaches 45 touches or has the higher score when time expires in the final round. -

Basic Actor Combatant Glossary 2012

= BASIC ACTOR COMBATANT GLOSSARY March 2, 2012 This is a living document and while Fight Directors Canada seeks to keep this glossary up to date it is simply impossible to list all terms or techniques. Individual teachers may add to what is listed or suggest an alternative meaning or explanation for a particular term or technique. If there is a disagreement between what is written and what is taught in class the written test will err on side of the instructor. Section 1: General Stage Combat Terms Section 2: Footwork, Stance and Posture Section 2: Unarmed Section 3: Quarterstaff Section 4: Single Sword Section 5: Weapons and Accoutrements Section 6: Theatrical & Performance Section 7: Alternate Terms Section 8: Diagrams All references and definitions originally taken from, ‘The Complete Encyclopedia of Arms and Armour’ Claude Blair & Leonid Tarassuk, ‘The Martini A-Z of Fencing’ E.D. Morton, ‘The Art and History of Personal Combat’ Arthur Wise. They were subsequently edited by Todd Campbell, Siobhán Richardson, Kevin Robinson, Casey Hudecki, Daniel Levinson, Paul Gelieanu, Ian Rose, Simon Fon and Kirsten Gundlack Fight Directors, Canada wishes to express their gratitude to the above named authors and editors for their invaluable assistance. FDC Basic Actor Combatant Glossary – 02 25 2012 page 1 of 18 SECTION 1: GENERAL STAGE COMBAT TERMS SECTION 1: GENERAL STAGE COMBAT TERMS aikido roll: A roll that resembles the shoulder roll but rather than using both hand and arms to lower the body to the floor the dominate arm is curved and used to guide the upper body to the floor. -

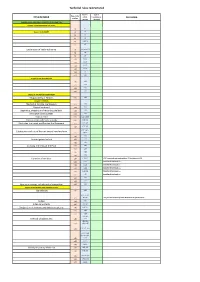

Technical Rules Restructured

Technical rules restructured Former Type of New article article inconsistency TITLE IN INDEX number Correction number detected GENERAL RULES AND RULES COMMON TO ALL WEAPONS Chapter 1: APPLICATION OF THE RULES t.1 t.1 Chapter 2: GLOSSARY t.2 t.2 t.3 t.3 t.4 t.4 t.5 t.107.1 t.6 t.5 Explanation of technical terms t.7 footnote (1) t.8 t.6 t.9 t.7 t.10 t.8.1 t.11 t.8.2 t.12 t.8.3 t.13 t.8.4 t.14 t.9 t.15 t.10 Chapter 3: THE FIELD OF PLAY t.16 t.11 t.17 t.12 t.18 t.13 t.19 t.14 Chapter 4: THE FENCER'S EQUIPMENT Responsibility of Fencers t.20 t.15 Chapter 5: FENCING Method of Holding the Weapon t.21 t.16 Coming on guard t.22 t.17 Beginning, stopping and restarting the bout t.23 t.18 Fencing at close quarters t.24 t.19 Corps a corps t.25 t.20, t.63.1 Corps a corps and fleche attacks t.26 t.63.3-4 Displacing the target and Passing the Opponent t.27 t.21.1/2 t.28 t.21.3-5 Substitution and use of the non-sword hand and arm t.22.1 & 3, t.29 t.72.2 t.30 t.23 Ground gained or lost t.31 t.24 t.32 t.25 Crossing the limits of the Piste t.33 t.26 t.34 t.27 t.35 t.28 t.36 t.29 Duration of the bout t.37 t.30,1-2 t.30.3 removed and replaced by o.17 that became t.38 t.38 o.17 transfer from book o. -

Fencing Club By-Laws: Ranking System

Fencing Club By-Laws: Ranking System Ranks are marked by colored bands beneath the shoulder patch. Testing occurs on individual occasions as determined by the Head Instructor. Members wishing to test can do so only if the Head Instructor offers to perform the testing. If a member wishes for a testing, the candidate cannot bring the request to the Head Instructor's attention, but must instead convince a member in good standing of at least the rank he/she wishes to test for (and at least the 2nd rank) to act as a sponsor on his/her behalf. This sponsor is also responsible for making sure the candidate is adequately prepared for the rank testing. When the testing occurs, all actions requiring 2 people will be performed by the candidate and her/his sponsor. The Head Instructor (the tester) will direct the actions and observe so as to score the candidate. The candidate should not be penalized for mistakes made by the sponsor; instead, the Head Instructor should ask them to repeat the action. Each rank confers upon the fencer a set of permissions to accompany their new rank. First Rank – Yellow Band - Beginning Foil Requirements: A) Length of attendance: Minimum attendance time before testing: 15 practices, with discretion for those with previous experience B) Candidate should have participated in at least two assaults previously with instructors. The Testing: The purpose of the 1st rank testing is for the candidate to demonstrate the knowledge and ability needed to fence safely with the foil in a bout. A) Candidate must demonstrate the following skills/techniques: Notice, all techniques should be done from a proper guard, attacks should be done with a properly executed lunge, etc. -

The Most Common Mistakes Beginning Rapier Students Make - Their Consequences and How to Avoid Them

The Most Common Mistakes Beginning Rapier Students Make - Their Consequences and How to Avoid Them. by Tom Leoni ©2005 As with most demanding disciplines, fencing has its set of common beginners’ mistakes. Having practiced, taught and observed historical fencers of all levels for over a decade, I have compiled a list of the more obvious and recurring ones. Interestingly, these are mistakes that, if not cured early, crystallize into bad habits that are very hard to amend later on. These mistakes are in both understanding and performance - often in both at the same time (the former being a prerequisite for the latter). I have outlined each point so as to list the mistake, the negative consequences deriving from it and my recommendations on how to correct it. Although I have purposely confined this discussion to the rapier, please note that many of these mistakes/habits are applicable to other fencing disciplines. Also, please note that the actions and situations I describe imply a somewhat formalized training intent based on historical sources. Many who enjoy swords casually and do not have the opportunity to train more formally may not identify with these points. Mistake: Obsessing too much about ideal rapier length. Consequences: Illusion that technical or theoretical shortcomings are "the rapier’s fault," resulting in failure to address them. Correction: Get a well-balanced rapier that works for you and then give it no more thought. Masters such as Alfieri and Capoferro specify that a rapier should be proportionate to the height of the fencer - it should comfortably stand under the armpit. -

Introduction to Rapier

INTRODUCTION TO RAPIER Based on the teachings of Ridolfo Capo Ferro, in his treatise first published in 1610. A WORKBOOK By Nick Thomas Instructor and co-founder of the © 2016 Academy of Historical Fencing Version 1 Introduction The rapier is the iconic sword of the renaissance, but it is often misunderstood due to poor representation in popular culture. The reality of the rapier is that it was a brutal and efficient killer. So much so that in Britain it was often considered a bullies or murderers weapon. Because to use a rapier against a person is to attempt to kill them, and not just defend oneself. A result of the heavy emphasis on point work and the horrendous internal damage that such thrust work inflicts. Rapier teachings were first brought to Britain in the 1570’s, and soon became the dominant weapon for civilian wear. Of course many weapons that were not so different were also used in the military, featuring the same guards and slightly lighter and broader blades. The rapier was very commonly used with offhand weapons, and Capo Ferro covers a range of them. However for this work book, we will focus on single sword, which is the foundation of the system. This class is brought to you by the Academy of Historical Fencing (UK) www.historicalfencing.co.uk If you have any questions about the class or fencing practice in general, feel free to contact us – [email protected] Overview of the weapon The First thing to accept as someone who already studies one form or another of European swordsmanship, is that you should not treat the rapier as something alien to you. -

The Art of Defence on Foot with the Broad Sword and Sabre

THE ART OF DEFENCE ON FOOT WITH THE BROAD SWORD AND SABRE FOURTH EDITION BY CHARLES ROWORTH 1824 TRANSCRIBED. RESTORED AND INTRODUCED BY NICK THOMAS INSTRUCTOR AND CO-FOUNDER OF THE ACADEMY OF HISTORICAL FENCING (UK) Presented below is a complete reconstruction of the fourth edition of Charles Roworth's 'Art of Defence', or AOD as it is sometimes now known. The AOD is one of the most important references on British swordsmanship on foot in the Napoleonic period, The British army did not adopt an official infantry sword system until after war's end. However, when they did, it was based on this style depicted by Charles Roworth, as well as Henry Angelo Senior, whose son created the official system in 1817, based firmly on his father’s methods. Despite not being an official system, these 'broadsword' methods were widespread throughout the 18th century. In the case of Roworth's AOD manual, it was recommended for purchase and use by British officers in many publications of the time. They are also well referenced to have been taught in many military units. Roworth's manuals give the most in-depth insight into infantry sword combat in this period, and likely served as the basis of sword training for many in the army and militia of the day. As well as a method for those elsewhere, such as in America, where this edition was published. The Art of Defence was first published in 1798. This second edition was also published in the same year, and though very similar, it features a number of changes to both text and illustration. -

The Fight Master, October 1978, Vol. 1 Issue 3

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Fight Master Magazine The Society of American Fight Directors 10-1978 The Fight Master, October 1978, Vol. 1 Issue 3 The Society of American Fight Directors Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/fight Part of the Acting Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation The Society of American Fight Directors, "The Fight Master, October 1978, Vol. 1 Issue 3" (1978). Fight Master Magazine. 3. https://mds.marshall.edu/fight/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Society of American Fight Directors at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fight Master Magazine by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. the Property of the ~.ltde±ti .of fi9bt J\mericmt Jlfigl1t Ji}tr£cfon_; rnasteu tbe societiY o,i: ameuican ,i:igbt <liuectons '1 IMlt'I' ------------------------------ REPLICA SWORDS 'rhe· Magazine of the Society of American Fight Directors We carry a wide selection of replica No. 3 October 1978 swords for theatrical and decorative use. Editor - Mike McGraw Lay-out - David L. Boushey RECOMMENDED BY THE ,'1 SOCIETY OF AMERICAN FIGHT DIRECTORS Typed and Duplicated by Mike McGraw I *************************************** ~oci~ty of American Yi£ht Directors The second Society of Fight Directors in the world has been I incorporated in Seattle, Washington. Its founder is David I IIi Boushey, Overseas Affiliate of the Society of British Fight ' Directors. OFFICERS: President - David L.