William Gillette and the Stage of Enterprise Catherine Maxwell Marks University of Massachusetts Amherst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gillette Case Intrigues Renovators Author

GILLETTE CASE INTRIGUES RENOVATORS Associated Press lated over the years as one of the nation's leading actors. The resulting moisture problems haunted Gillette Most of Gillette's success had come from his portrayal, on long after the castle's completion by the renowned EAST HADDAM — Over the past two years, David stage and screen, of the fictional detective Sherlock Hartford firm of Porteus & Walker. And they continue Barkin has found himself investigating a mortar mys- Holmes, from the novels by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. to this day, as workers feverishly rebuild stone walls tery perhaps only Sherlock Holmes could unravel. surrounding the castle and administrators prepare Barkin, a New Haven architect, has been lurking in a Gillette Castle — closed now for nearly three years as it and the surrounding 184 acres of state park grounds plans for a visitor's center, new exhibits and the re- damp and musty castle, muttering things like, "What introduction of Gillette's famed miniature railroad. did he mean here?" as he uncovers mustard, green, red, undergo a $10.1 million restoration and improvement program — had been intended by its eccentric first Most of the improvements will coincide with the cas- black and burgundy mortar — the gooey material that, tle's planned reopening on Memorial Day weekend once dry, holds stone walls together. owner to resemble a ruin on the Rhine River in Germa- ny. Part of the aesthetic, massive fieldstone walls un- "He had a leaking castle from the day he built it," PLEASE SEE GILLETTE, PAGE B5 Barkin says of William Gillette, the man who designed dulate unevenly, allowing water to pool in certain and paid nearly $1 million for the castle in 1919, using areas — especially around the windows, which display his ripe imagination and the money he had accumu- evidence of awnings once having been deployed. -

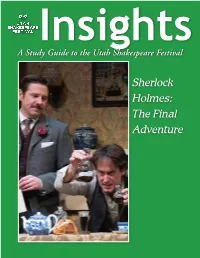

Sherlock Holmes: the Final Adventure the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2014, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Brian Vaughn (left) and J. Todd Adams in Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure, 2015. Contents Sherlock InformationHolmes: on the PlayThe Final Synopsis 4 Characters 5 About the AdventurePlaywright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play The Final Adventures of Sherlock Holmes? 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The play begins with the announcement of the death of Sherlock Holmes. It is 1891 London; and Dr. Watson, Holmes’s trusty colleague and loyal friend, tells the story of the famous detective’s last adventure. -

Li^^Ksehtarions

PAGE 4 THE INDIANAPOLIS TIMES JAN. 15, 1936 Louise Essex Proves Idea Coming ,Here Friday on Screens and Stage of Moving Picture Theaters Thrills and That Musicians of State Chills Make Rank With World's Finest Movie Short Cellist, Appearing With Indianapolis Symphony, Presents Graphic Newsreel Pictures Saint-Saens Concerto, Bringing to Authority, It Catch Tragedy as Depth of Feeling, Fluent Dexterity. It Stalks. BY JAMES THRASHER This week has brought us two exceptional performances bv Indian- When a newsreel cameraman goes apolis musicians. They should help to dispel the false, but still prevalent, after his story he usually geta it. notion that the soil of artistic growth Is confined to continental Europe. But he also gets more than the Louise Essex, cellist and soloist with the Indianapolis Symphony Orches- censors or editors will allow in the tra last night, reaffirmed the impression created by Bomar Cramer's piano final reel. recital Sunday—that one may ascend the slopes of Parnassus from the What is left over is saved, and prairies of Indiana. some of the most interesting of theae Miss Essex delayed her debut in excerpts from the world’s pictorial public recital until last night, history are to be shown as “Camera though she had gained an enviable Thrills,” at the Circle beginning reputation in Europe and our East- Blueprints Friday. ern cities. It seems a wise decision, Aid Charles E. Ford, head of Universal for she came to us as a well- Newsreel, sponsored in Indianapolis equipped and gifted musician with- by Tiie Times, has arranged these out deficiencies which local pride in Film-Making many scenes of action and real life might seek to excuse. -

Hollis Street Theatre Passers-By Program

MOLLIS ST Tli EATRE Charles Froha\a/\i RICH HARRIS LESSEES 5c MANAGERS x x x xxxx ; ; .; x x x x x x x x x x x x x , x , ,; x x , x . , j; HOLLIS ST. THEATRE PROGRAM 3 g | "YOU CAN RELY ON LEWANDOS”! CLEANSERS S DYERS I LAUNDERERS | | I ESTABLISHED 1829 LARGEST IN AMERICA | High Class Work Returned in a Few Days I LEWANDOS | BOSTON SHOPS 17 TEMPLE PLACE and 284 BOYLSTON STREET Phone 555 Oxford Phone 3900 Back Bay BRANCH SHOPS Brookline Watertown Cambridge 1310 Beacon Stree 1 Galen Street 1274 Massachusetts Ave Phone 5030 Phone Newton North 300 Phone Cambridge 945 Roxbury Lynn Salem 2206 Washington Street 70 Market Street 187 Essex Street Phone Roxbury 92 Phone 1860 Phone 1800 Also New York Philadelphia Hartford Providence Albany Washington New Haven Newport Rochester Baltimore Bridgeport Portland Worcester Springfield EXECUTIVE OFFICES 286 BOYLSTON STREET BOSTON YOU CAN RELY ON LEWANDOS fv •>' v >' v .w .v .v >v m-mvww.v.vm'. v.v v mm v :cv. $$$•$ .v.v. :v. .v :> i 4 HOLLIS ST. THEATRE PROGRAM >j I PALMIST FLETCHER I ^ (Lat© of New York City) £• : >; | The World-Renowned Adviser | of of the $: Has Long Enjoyed the Confidence Many Best People in | j; America and Europe § S If there are changes in business, trouble, illness or accidents, happy or dark | § days in store, he sees it all in the lines of your hand and gives you invalu- | | able advice. The right word at the right moment saves many a mistake. % J There are always two ways in life — PSYCHIC PALMISTRY enables $ you to choose the right >: “Fletcher saved me serious mistakes. -

Charlie Chaplin's

Goodwins, F and James, D and Kamin, D (2017) Charlie Chaplin’s Red Letter Days: At Work with the Comic Genius. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1442278099 Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/618556/ Version: Submitted Version Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Charlie Chaplin’s Red Letter Days At Work with the Comic Genius By Fred Goodwins Edited by Dr. David James Annotated by Dan Kamin Table of Contents Introduction: Red Letter Days 1. Charlie’s “Last” Film 2. Charlie has to “Flit” from his Studio 3. Charlie Chaplin Sends His Famous Moustache to the Red Letter 4. Charlie Chaplin’s ‘Lost Sheep’ 5. How Charlie Chaplin Got His £300 a Week Salary 6. A Straw Hat and a Puff of Wind 7. A bombshell that put Charlie Chaplin ‘on his back’ 8. When Charlie Chaplin Cried Like a Kid 9. Excitement Runs High When Charlie Chaplin “Comes Home.” 10. Charlie “On the Job” Again 11. Rehearsing for “The Floor-Walker” 12. Charlie Chaplin Talks of Other Days 13. Celebrating Charlie Chaplin’s Birthday 14. Charlie’s Wireless Message to Edna 15. Charlie Poses for “The Fireman.” 16. Charlie Chaplin’s Love for His Mother 17. Chaplin’s Success in “The Floorwalker” 18. A Chaplin Rehearsal Isn’t All Fun 19. Billy Helps to Entertain the Ladies 20. “Do I Look Worried?” 21. Playing the Part of Half a Cow! 22. “Twelve O’clock”—Charlie’s One-Man Show 23. “Speak Out Your Parts,” Says Charlie 24. Charlie’s Doings Up to Date 25. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2021

Jan 21 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) did not gather in New York to celebrate the Great Detective’s 167th birthday this year, but the somewhat shorter long weekend offered plenty of events, thanks to Zoom and other modern technol- ogy. Detailed reports will be available soon at the web-site of The Baker Street Irregulars <www.bakerstreetirregulars.com>, but here are few brief paragraphs to tide you over: The BSI’s Distinguished Speaker on Thursday was Andrew Lycett, the author of two fine books about Conan Doyle; his topic was “Conan Doyle’s Questing World” (and close to 400 people were able to attend the virtual lecture); the event also included the announcement by Steve Rothman, editor of the Baker Street Journal, of the winner of the Morley-Montgomery Award for the best article the BSJ last year: Jessica Schilling (for her “Just His Type: An Analysis of the Découpé Warning in The Hound of the Baskervilles”). Irregulars and guests gathered on Friday for the BSI’s annual dinner, with Andrew Joffe offering the traditional first toast to Nina Singleton as The Woman, and the program continued with the usual toasts, rituals, and pap- ers; this year the toast to Mrs. Hudson was delivered by the lady herself, splendidly impersonated by Denny Dobry from his recreation of the sitting- room at 221B Baker Street. Mike Kean (the “Wiggins” of the BSI) presented the Birthday Honours (Irregular Shillings and Investitures) to Dan Andri- acco (St. Saviour’s Near King’s Cross), Deborah Clark (Mrs. Cecil Forres- ter), Carla Coupe (London Bridge), Ann Margaret Lewis (The Polyphonic Mo- tets of Lassus), Steve Mason (The Fortescue Scholarship), Ashley Polasek (Singlestick), Svend Ranild (A “Copenhagen” Label), Ray Riethmeier (Mor- rison, Morrison, and Dodd), Alan Rettig (The Red Lamp), and Tracy Revels (A Black Sequin-Covered Dinner-Dress). -

INTRODUCTION Xl Othello a 'Black Devil' and Desdemona's 'Most Filthy

INTRODUCTION xl Othello a 'black devil' and Desdemona's 'most filthy bargain' ^ we cannot doubt that she speaks the mind of many an Englishwoman in the seventeenth-century audience. If anyone imagines that England at that date was unconscious of the 'colour-bar' they cannot have read Othello with any care? And only those who have not read the play at all could suppose that Shake speare shared the prejudice, inasmuch as Othello is his noblest soldier and he obviously exerted himself to represent him as a spirit of the rarest quality. How significant too is the entry he gives him! After listening for 180 lines of the opening scene to the obscene suggestions of Roderigo and lago and the cries of the outraged Brabantio we find ourselves in the presence of one, not only rich in honours won in the service of Venice, and fetching his 'life and being from men of royal siege',3 but personally a prince among men. Before such dignity, self-possession and serene sense of power, racial prejudice dwindles to a petty stupidity; and when Othello has told the lovely story of his courtshipj and Desdemona has in the Duke's Council- chamber, simply and without a moment's hesitation, preferred her black husband to her white father, we have to admit that the union of these two grand persons, * 5. 2.134, 160. The Devil, now for some reason become red, was black in the medieval and post-medievcil world. Thus 'Moors' had 'the complexion of a devil' {Merchant of Venice, i. 2. -

NEW AMSTERDAM THEATER, 214 West 42Nd Street, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 23, 1979, Designation List 129 LP-1026 NEW AMSTERDAM THEATER, 214 West 42nd Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1902-03; architects Herts & Tallant. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1013, Lot 39. On January 9, 1979, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the New Amsterdam Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 4). The hearing was continued to March 13, 1979 (Item No. 3). Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. A total of 16 witnesses spoke in favor of designation at the two hearings. There were two speakers in opposition to designation. Several letters and statements supporting designation have been received. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The New Amsterdam Theater, built in 1902-03 for the theatrical producers Klaw & Erlanger, was for many years one of the most pres tigious Time Square theaters and horne of the famous Ziegfeld Follies. Designed by the noted theater architects, Herts & Tallant, the New Amsterdam Theater achieved distinction both for its functions and for its artistic program. More than just a theater, the structure was planned, at the request of Klaw & Erlanger, to incorporate two performing spaces with an office tower to house their varied theatrical interests. Even more importantly, however, the New Amsterdam is a rare example of Art Nouveau architecture in New York City, and, as such, is a major artistic statement by Herts & Tallant. Working in conjunction with sculptors, painters, and other craftsmen, they used the Art Nouveau style to carry out a dual theme--the representation of the spirit of drama and the theater and the representation of New Amsterdam in its historical sense as the city of New York. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

The Wicked Beginnings of a Baker Street Classic!

The Wicked Beginnings of a Baker Street Classic! by Ray Betzner From The Baker Street Journal Vol. 57, No. 1 (Spring 2007), pp. 18 - 27. www.BakerStreetJournal.com The Baker Street Journal continues to be the leading Sherlockian publication since its founding in 1946 by Edgar W. Smith. With both serious scholarship and articles that “play the game,” the Journal is essential reading for anyone interested in Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and a world where it is always 1895. www.BakerStreetJournal.com THE WICKED BEGINNINGS OF A BAKER STREET CLASSIC! by RAY BETZNER In the early 1930s, when pulps were the guilty pleasures of the American maga- zine business, Real Detective was just another bedsheet promising sex, sin, and sensationalism for a mere two bits. With a color cover that featured a sultry moll, a gun-toting cop, or a sneering mobster, it assured the reader that when he got the magazine back to his garage or basement, he would be entertained by the kind of delights not found in The Bookman or The Atlantic Monthly. And yet, for a moment in December 1932, a single article featuring the world’s first consulting detective elevated the standards of Real Detective to something approaching respectability. Starting on page 50, between “Manhattan News Flash” (featuring the kidnapping of little John Arthur Russell) and “Rah! Rah! Rah! Rotgut and Rotters of the ’32 Campus” (by Densmore Dugan ’33) is a three-quarter-page illustration by Frederic Dorr Steele showing Sherlock Holmes in his dressing gown, standing beneath the headline: “Mr. Holmes of Baker Street: The Discovery of the Great Detective’s Home in London.” Com- pared with “I am a ‘Slave!’ The Tragic Confession of a Girl who ‘Went Wrong,’” the revelations behind an actual identification for 221B seems posi- tively quaint. -

Hollis Street Theatre the Concert Program

HOLLIS ST Tli EATRE § [7 ^ Charles Frohmaai RICH 5c HARRIS LESSEES 5r MANAGERS HOLLIS ST, THEATRE PROGRAM. WEEK OF JANUARY 1. 1912 3 The Refinements of Our Work are most apparent when compared with the work of ordinary cleaners Unexcelled facilities up - to- the - minute equipment and years of experience in CLEANSING AND DYEING Make our work distinctive in its thoroughness ARTICLES RETURNED IN A SHORT TIME CURTAINS GOWNS MENS CLOTHES BLANKETS WAISTS OVERCOATS DRAPERIES SASHES SUITS GLOVES Carefully cleansed properly finished and inspected before returning LEWANDOS CLEANSERS DYERS LAUNDERERS BOSTON SHOPS 17 Temple Place 284 Boylston Street Phone Oxford 555 Phone Back Bay 3900 ROXBURY CAMBRIDGE 2206 Washington Street 1274 Massachusetts Avenue Phone Roxbury 92 Phone Cambridge 945 WATERTOWN LYNN Galen Street (with Newton Deliveries) 70 Market Street Phone Newton North 300 Phone Lynn 1860 SOUTH BOSTON SALEM 469A Broadway 209 Essex Street Phone South Boston 600 Phone Salem 1800 ALSO Portland Worcester Springfield Providence Newport Hartford New Haven Bridgeport Albany Rochester Washington Philadelphia Baltimore New York TELEPHONE CONNECTION AT ALL SHOPS DELIVERY SYSTEM BY OUR OWN MOTORS AND TEAMS “You Can Rely on Lewandos” ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... - ... ^ .. .. ..- - ... .. - - ^ - , . * ^ - r rr T r rn) r v |r r mn^Tr n i. 'nn I 4 HOLLIS ST. THEATRE PROGRAM. WEEK OF JANUARY 1, 1912. THE WORLD RENOWNED i; I Palmist Fletcher (Late of New York City) Do you wish to know what is before you ? Are you making changes in business ? Have you family troubles or personal disagreements? Are you worried over your affairs, and uncertain as to which way to turn? Are you in doubt as to your course? Do you wish to succeed? In fact all that relates to your welfare, be it good or bad, FLETCHER can tell you at a glance. -

Days of My Years Sir Melville Macnaghten

DAYS OF MY YEARS SIR MELVILLE MACNAGHTEN Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/daysofmyyearsOOmacnrich DAYS OF MY YEARS 1 LONDON: EDWARD ARNOLD. DAYS OF MY YEARS BY Sir MELVILLE L. MACNAGHTEN, C.B, I.ATE CHIEF OF THE CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION DEPARTMENT SCOTLAND YARD WITH PORTRAIT LONDON EDWARD ARNOLD 1914 [A /I rights reserved'] ,«;"<* K^^'' TO MY DEAR FRIEND AND OLD COLLEAGUE Sir EDWARD RICHARD HENRY G.C.V.O.. K.C.B., C.S.I. THE BEST ALL ROUND POLICEMAN OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY A MAN TO WHOM LONDON OWES MORE THAN IT KNOWS 324476 PREFACE " " O mihi prateritos referat si Jupiter annos ! The days of my years are not yet threescore and ten, but they are within an easy decade of the allotted span of man's life. Taken all round, those sixty years have been so happy that I would, an I could, live almost every day of every year over again. Sam Weller's knowledge of London life was said to have been extensive and peculiar. My experiences have also been of a varied nature, and certain days in many years have been not without incidents which may be found of some interest to a patient reader, and specially so if his, or her, tastes he in the direction of police work in general and Metropolitan murders in particular. Autobiographies are, for the most part, dull viii PREFACE stuff : I would attempt nothing of the kind, but only to set out certain episodes in a disjointed and fragmentary manner.