Volume 26, Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SM 9 the Methods of Ethnology

Savage Minds Occasional Papers No. 9 The Methods of Ethnology By Franz Boas Edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub First edition, 18 January, 2014 Savage Minds Occasional Papers 1. The Superorganic by Alfred Kroeber, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 2. Responses to “The Superorganic”: Texts by Alexander Goldenweiser and Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 3. The History of the Personality of Anthropology by Alfred Kroeber, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 4. Culture and Ethnology by Robert Lowie, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 5. Culture, Genuine and Spurious by Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 6. Culture in the Melting-Pot by Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 7. Anthropology and the Humanities by Ruth Benedict, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 8. Configurations of Culture in North America, by Ruth Benedict, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 9. The Methods of Ethnology, by Franz Boas, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub Copyright information This original work is copyright by Alex Golub, 2013. The author has issued the work under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license. You are free • to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work • to remix - to adapt the work Under the following conditions • attribution - you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author • noncommercial - you may not use this work for commercial purposes • share alike - if you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one This work includes excerpts from Boas, Franz. -

Trust Mechanisms, Cultural Difference and Poverty Alleviation

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 20 (2018) Issue 2 Article 8 Trust Mechanisms, Cultural Difference and Poverty Alleviation Lihua Guo MinZu University of China Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Economics Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Guo, Lihua. "Trust Mechanisms, Cultural Difference and Poverty Alleviation." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 20.2 (2018): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.3229> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 106 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

Poverty-Related Topics Found in Dissertations: a Bibliography. INS1ITUTION Wisconsin Univ., Madison

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 135 540 RC 009 699 AUTEJOR O'Neill, Mara, Comp.; And Others TITLE Poverty-Related Topics Found in Dissertations: A Bibliography. INS1ITUTION Wisconsin Univ., Madison. Inst. for Research on Poverty. PUB LATE 76 NOTE 77p. EDRS PRICE 1E-$0.83 HC-$4.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indians; *Annotated Bibliographies; Attitudes; Bilingual Education; Community Involvement; Culturally Disadvantaged; *Doctoral Theses; *Economically Disadvantaged; *Economic Disadvantagement; *Economic Research; Government Role; Guaranteed Income; Human Services; Low Income Groups; Manpower Development; Mexican Americans; Negroes; Clder Adults; Politics; Poverty Programs; Dural Population; Social Services; *Socioeconomic Influences; Welfare; Working Women IDENTIFIERS Chicanos ABSIRACI Arranged alphabetically by main toPic, this bibliography cites 322 doctoral dissertations, written between 1970 and 1974, pertaining to various aspects of poverty. Where possible, annotations have been written to present the kernel idea of the work. Im many instances, additional subject headings which reflect important secondary thrusts are also included. Topics covered include: rural poverty; acceso and delivery of services (i.e., food, health, medical, social, and family planning services); employment; health care; legal services; public welfare; adoptions, transracial; the aged; anomie; antipoverty programs; attitudes of Blacks, Congressmen, minorities, residents, retailers, and the poor; bilingual-bicultural education; discrimination dn employment and housing; social services; social welfare; Blacks, Chicanos, and Puerto Ricans; participation of poor in decision making; poverty in history; education; community participation; culture of poverty; and attitudes toward fertility, social services, welfare, and the poor. Author and zubject indices are included to facilitate the location of a work. The dicsertations are available at the institutions wherethe degrees were earned or from University Microfilms. -

Teaching Against Essentialism and the ''Culture of Poverty''

6 TEACHING AGAINST ESSENTIALISM AND THE ‘‘CULTURE OF POVERTY’’ Paul C. Gorski randma tends to stretch vowel sounds, drawing extended air time out of them in her sweet Appalachian twang. Where D.C.-born G folk like me give a door a push, she gives it a poosh. Where I crave candy, she offers sweeter-sounding cane-dee. Her vocabulary, as well, is of a western Maryland mountain variety, unassuming and undisturbed by slangy language or new age idiom. To her, a refrigerator is still a Frigidaire; or, more precisely, a freegeedaire; neighbors live across the way. Her children, including my mother, say she’s never cursed and only occasionally lets fly her fiercest expression: Great day in the mornin’! Despite growing up in poverty, Grandma isn’t uneducated or lacking in contemporary wits, as one might presume based upon the ‘‘culture of pov- erty’’ paradigm that dominates today’s understandings of poverty and schooling in the United States. She graduated first in her high school class. Later, the year she turned 50, she completed college and became a nurse. I’ve never been tempted to ‘‘correct’’ Grandma’s language, nor do I feel embarrassed when she talks about how my Uncle Terry’s gone a’feesheen’. She doesn’t need my diction or vocabulary to give meaning to her world. She certainly doesn’t need to be freed from the grasp of a mythical ‘‘culture of poverty’’ or its fictional ‘‘language registers.’’ What needs a’fixin’ is not Grandma’s dispositions or behaviors, but those of a society that sees only her poverty and, as a result, labels her—the beloved matriarch of an extended 84 Copyright 2012 Stylus Publishing, LLC www.Styluspub.com ................ -

Culture of Poverty’ in a Major Publication

Poerty and Gender in Deeloping Nations United Nations Centre for Human Settlements 1999 Women’s Poverty research throughout history has been more Rights to Land, Housing and Property in Postconflict Situations successful at reflecting the biases of an investigator’s and During Reconstruction: A Global Oeriew. Land Man- society than at analyzing the experience of poverty. F agement Series 9. UNCHS, Nairobi, Kenya The state of poverty research in any given country United Nations Development Programme 1998 Human De- emerges almost as a litmus for gauging contemporary elopment Report 1998. Published annually since 1990 with different emphases. Oxford University Press, New York social attitudes toward inequality and marginaliz- United Nations Research Institution for Social Development ation. For example, while Lewis’s books are read by a (UNRISD), United Nations Development Programme US public as an individualistic interpretation of the (UNDP), Centre for Development Studies, Kerala 1999 persistence of poverty that blames victims, in France Gender, Poerty and Well-Being: Indicators and Strategies. his work is interpreted as a critique of society’s failure Report of the UNRISD, UNDP and CDS International to remedy the injuries of class-based inequality under Workshop, November 1997. UNRISD, Geneva free market capitalism. World Bank 2000 World Deelopment Report 2000\1: Attacking Poerty. Oxford University Press, New York I. Tinker 2. Defining the Culture of Poerty The socialist sociologist Michael Harrington was the first prominent academic to use the phrase ‘culture of poverty’ in a major publication. His book, The Other America, documented rural poverty in Appalachia Poverty, Culture of and represented a moral call to action that anticipated the War on Poverty initiated by President Johnson in The culture of poverty concept was developed in the 1964 (Harrington 1962). -

Global Reconfigurations of Poverty and the Public: Anthropological Perspectives and Ethnographic Challenges

Global Reconfigurations of Poverty and the Public: Anthropological perspectives and ethnographic challenges Responsible Institution: Department of Social Anthropology, University of Bergen (UiB) Disciplines: Social Anthropology, History, Cultural Studies, Sociology Course Leader: Vigdis Broch-Due, Professor of International Poverty Research, Department of Social Anthropology, University of Bergen Invited Course Leaders: Jean Comaroff, Professor of Anthropology and of Social Sciences, Department of Anthropology, University of Chicago Akhil Gupta, Professor and Chair, IDP South Asian Studies Department of Anthropology and International Institute, UCLA Alice O'Connor, Associate Professor,Department of History, University of California, Santa Barbara & Director for the programs on Persistent Urban Poverty and International Migration at the Social Science Research Council (USA) Course Description: “The Poor”, - a group figuring so prominently in contemporary media and the discourses of aid, human rights and global insecurity, in fact consist largely of the classical subjects of anthropology. While anthropologists continue to produce ethnography about the specificities of different peoples, few address the problems that arise when all that cultural diversity is subsumed under the headings “Poverty” or “the Poor”. Anthropologists who do address questions of poverty are often sidelined in increasingly globalised policy debates that set quantitative “goals” and seek measurable formulae for attaining them. Why are anthropologists vocal on the plight of distinct peoples but silent or marginalized on the subject of the “the poor”? How do we research, theorize, let alone compose ethnographies, which focus on such a diffuse, standardised, globalised entity as “poverty” and “the poor”? Should we? And what are the consequences of remaining on the sidelines? These questions outline the analytical challenges of this PhD course. -

SM 11 Cultural Anthropology and Psychiatry

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by eVols at University of Hawaii at Manoa Savage Minds Occasional Papers No. 11 Cultural Anthropology and Psychiatry By Edward Sapir Edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub First edition, 11 March, 2014 Savage Minds Occasional Papers 1. The Superorganic by Alfred Kroeber, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 2. Responses to “The Superorganic”: Texts by Alexander Goldenweiser and Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 3. The History of the Personality of Anthropology by Alfred Kroeber, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 4. Culture and Ethnology by Robert Lowie, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 5. Culture, Genuine and Spurious by Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 6. Culture in the Melting-Pot by Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 7. Anthropology and the Humanities by Ruth Benedict, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 8. Configurations of Culture in North America, by Ruth Benedict, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 9. The Methods of Ethnology, by Franz Boas, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 10. The Science of Culture: The Bearing of Anthropology on Contemporary Thought, by Ruth Benedict, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 11. Cultural Anthropology and Psychiatry, by Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub Copyright information This original work is copyright by Alex Golub, 2014. The author has issued the work under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license. -

Charles Wagley on Changes in Tupí-Guaraní Kinship Classifications Transformações Nas Classificações De Parentesco Tupi-Guarani Segundo Charles Wagley

Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi. Cienc. Hum., Belém, v. 9, n. 3, p. 645-659, set.-dez. 2014 Charles Wagley on changes in Tupí-Guaraní kinship classifications Transformações nas classificações de parentesco Tupi-Guarani segundo Charles Wagley William Balée Tulane University. New Orleans, USA Abstract: Charles Wagley contributed significantly to the ethnographic study of culture and society in Brazil. In addition to his well- known work on both rural and urban Brazilian populations, Wagley was a pioneering ethnographer of indigenous societies in Brazil, especially the Tapirapé and Tenetehara, associated with the Tupí-Guaraní language family. In comparing these two societies specifically, Wagley was most interested in their kinship systems, especially the types of kinship or relationship terminology that these exhibited. In both cases, he found that what had once been probably classificatory, bifurcate-merging terminologies seem to have developed into more or less bifurcate-collateral (or Sudanese-like) terminologies, perhaps partly as a result of contact and depopulation. Recent research on kinship nomenclature and salience of relationship terms among the Ka’apor people, also speakers of a Tupí-Guaraní language, corroborates Wagley’s original insights and indicates their relevance to contemporary ethnography. Keywords: Relationship terms. Tupí-Guaraní. Amazonia. Ethnography. Resumo: Charles Wagley contribuiu de maneira significativa para o estudo etnográfico da cultura e sociedade no Brasil. Além de seu conhecido trabalho sobre as populações rurais e urbanas brasileiras, Wagley foi um etnógrafo pioneiro das sociedades indígenas no Brasil, especialmente os Tapirapé e Tenetehara, associados à família linguística Tupi-Guarani. Ao comparar especificamente essas duas sociedades, Wagley estava interessado, sobretudo, nos seus sistemas de parentesco, especialmente nos tipos de parentesco ou na terminologia para relacionamentos que elas apresentavam. -

“Absolutely Sort of Normal”: the Common Origins of the War on Poverty at Home and Abroad, 1961-1965

“ABSOLUTELY SORT OF NORMAL”: THE COMMON ORIGINS OF THE WAR ON POVERTY AT HOME AND ABROAD, 1961-1965 by DANIEL VICTOR AKSAMIT B.A., UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA, 2005 M.A., KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY, 2009 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2014 Abstract Scholars identify the early 1960s as the moment when Americans rediscovered poverty – as the time when Presidents, policymakers, and the public shifted their attention away from celebrating the affluence of the 1950s and toward directly helping poor people within the culture of poverty through major federal programs such as the Peace Corps and Job Corps. This dissertation argues that this moment should not be viewed as a rediscovery of poverty by Americans. Rather, it should be viewed as a paradigm shift that conceptually unified the understanding of both foreign and domestic privation within the concept of a culture of poverty. A culture of poverty equally hindered poor people all around the world, resulting in widespread illiteracy in India and juvenile delinquency in Indianapolis. Policymakers defined poverty less by employment rate or location (rural poverty in Ghana versus inner-city poverty in New York) and more by the cultural values of the poor people (apathy toward change, disdain for education, lack of planning for the future, and desire for immediate gratification). In a sense, the poor person who lived in the Philippines and the one who lived in Philadelphia became one. They suffered from the same cultural limitations and could be helped through the same remedy. -

Research in Progress

History of Anthropology Newsletter Volume 14 Issue 1 June 1987 Article 11 January 1987 Research in Progress Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation (1987) "Research in Progress," History of Anthropology Newsletter: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol14/iss1/11 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol14/iss1/11 For more information, please contact [email protected]. M. Sauri--"Excursionism and folklore: the Associacio d'Excursions Catalana" Antonio Vives--"Anthropology and science in nineteenth century Catalan culture" RESEARCH IN PROGRESS Brown (History, University of Winnepeg) is doing research on A. I. Hallowell's records of his field researches_: in Manitoba in the 1930s, and especially on his relationship with his prime informant, William Berens, drawing on the materials in the Library of the American Philosophical Society. Since Hallowell's papers seem not to include copies of his outgoing letters, she is interested in locating in the files of other anthropologists letters from Hallowell about his Berens River experiences--and would gladly pay for copying costs. Douglas R. Givens (St. Louis Community College, Meramec) is doing research on the role of biography in writing the history of Americanist archeology. Hans-Jurgen Hildebrandt (Mainz, West Germany) is working on a comprehensive bibliography of the primary and secondary literature of and on Johann Jakob Bachofen ( 1815-1887) for the hundredth anniversary of Bachofen's death. Melinda Kanner (Anthropology, Ohio State University) has been doing research on Margaret Mead, and on the nature of the relationship between biography and anthropology. -

'Culture of Poverty' Makes a Comeback

‘Culture of Poverty’ Makes a Comeback By PATRICIA COHEN, Published: October 17, 2010 NYTImes WebSite For more than 40 years, social scientists investigating the causes of poverty have tended to treat cultural explanations like Lord Voldemort: That Which Must Not Be Named. The reticence was a legacy of the ugly battles that erupted after Daniel Patrick Moynihan, then an assistant labor secretary in the Johnson administration, introduced the idea of a “culture of poverty” to the public in a startling 1965 report. Although Moynihan didn’t coin the phrase (that distinction belongs to the anthropologist Oscar Lewis), his description of the urban black family as caught in an inescapable “tangle of pathology” of unmarried mothers and welfare dependency was seen as attributing self-perpetuating moral deficiencies to black people, as if blaming them for their own misfortune. Moynihan’s analysis never lost its appeal to conservative thinkers, whose arguments ultimately succeeded when President Bill Clinton signed a bill in 1996 “ending welfare as we know it.” But in the overwhelmingly liberal ranks of academic sociology and anthropology the word “culture” became a live grenade, and the idea that attitudes and behavior patterns kept people poor was shunned. Now, after decades of silence, these scholars are speaking openly about you-know-what, conceding that culture and persistent poverty are enmeshed. “We’ve finally reached the stage where people aren’t afraid of being politically incorrect,” said Douglas S. Massey, a sociologist at Princeton who has argued that Moynihan was unfairly maligned. … The topic has generated interest on Capitol Hill because so much of the research intersects with policy debates. -

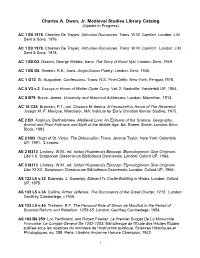

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy.