I Am Divine. So Are You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Configuring a Scatological Gaze in Trash Filmmaking Zoe Gross

Excremental Ecstasy, Divine Defecation and Revolting Reception: Configuring a Scatological Gaze in Trash Filmmaking Zoe Gross Scatology, for all the sordid formidability the term evokes, is not an es- pecially novel or unusual theme, stylistic technique or descriptor in film or filmic reception. Shit happens – to emphasise both the banality and perva- siveness of the cliché itself – on multiple levels of textuality, manifesting it- self in both the content and aesthetic of cinematic texts, and the ways we respond to them. We often refer to “shit films,” using an excremental vo- cabulary redolent of detritus, malaise and uncleanliness to denote their otherness and “badness”. That is, films of questionable taste, aesthetics, or value, are frequently delineated and defined by the defecatory: we describe them as “trash”, “crap”, “filth”, “sewerage”, “shithouse”. When considering cinematic purviews such as the b-film, exploitation, and shock or trash filmmaking, whose narratives are so often played out on the site of the gro- tesque body, a screenscape spectacularly splattered with bodily excess and waste is de rigeur. Here, the scatological is both often on blatant dis- play – shit is ejected, consumed, smeared, slung – and underpining or tinc- turing form and style, imbuing the text with a “shitty” aesthetic. In these kinds of films – which, as their various appellations tend to suggest, are de- fined themselves by their association with marginality, excess and trash, the underground, and the illicit – the abject body and its excretia not only act as a dominant visual landscape, but provide a kind of somatic, faecal COLLOQUY text theory critique 18 (2009). -

Ethos and Vision Statement

Khalsa Primary School Our Vision At Khalsa Primary we are helping our children grow in mind, body and spirit. We aim for excellence in academic, emotional and spiritual areas of understanding. Our children learn how to work with passion, ethics, honesty and self-discipline. They share their skills in service to the community, with love and without discrimination. They learn gratitude and self-discovery through learning how to connect with God. The whole school community aspires to work together as a genuine team, basing our daily practice in the five Sikh values of love, compassion, contentment, humility and truth Everyone is welcome at Khalsa This statement needs to be read in conjunction with the school’s statement on British Values 1 Khalsa Framework to help us deliver our Vision The Four Ofsted Areas of Evaluation The Three Pillars of Sikhism & Khalsa 1) Achievement of Pupils 1KK) Beyond Academic Achievement – Kirat Karni Progress Learning how to work: Attainment With passion, ethics, honesty and self-discipline SEND EYFS data 2) Quality of Teaching 2VC) Beyond Self – Vand Chakna Teaching strategies Community living: Learning Sharing our skills in service (Seva) with love and without Learning over time discrimination Teaching Assistants 3) Behaviour and Safety 3NJ) Beyond the Surface - Naam Japna Spiritual, Moral, Social, Cultural (SMSC) Towards the spiritual: Behaviour Learning gratitude and self-discovery through meditation on a Attendance journey towards purity of spirit through connecting with God Safety 4) Leadership & Management 4K) Khalsa Vision & School Strategic Planning Working together as a genuine, free community of people, in: Monitoring and evaluation Love (Pyar) Teacher Standards Compassion (Daya) Curriculum Contentment (Santokh) Capacity to lead improvement Humility (Nimarta) Governance Truth (Sat) Pupil preparation for democracy Parent engagement Partnership with other agencies Safeguarding 5. -

Adrian J. Fernandes Masters in Theology (Mth) Institute of Philosophy and Religion Jnana-Deepa Vidyapeeth Pune, Maharashtra [email protected]

Adrian J. Fernandes Masters in Theology (MTh) Institute of Philosophy and Religion Jnana-Deepa Vidyapeeth Pune, Maharashtra [email protected] An Appraisal on ‘Embracing the Other’ in Praxis: The Inherent Unifying Dynamics of Community Meal Services in Religion We know how special a meal is for a family and for any gathering. Eating together, being together and sharing from the same preparation builds bonds and deepens the commonality of a shared identity. This paper titled “An Appraisal on ‘Embracing the Other’ in Praxis: The Inherent Unifying Dynamics of Community Meal Services in Religion” attempts to present a practical approach of emulating the intrinsic values encapsulated within religious meal services. The presentation specifically focuses on Guru ka Langar in Sikhism and the Eucharist in Christianity. Guru ka Langar is a community kitchen run in the name of the Guru, usually attached to a Gurudwara. Guru Nanak, the first Guru of Sikhism, started this communal meal, the Langar, which has served two primary intended purposes; firstly in fostering the principle of equality between all peoples of the world regardless of religion, caste, colour, age, gender or social status and secondly to put into practice the spirit of humble, selfless social service, thus expressing the ethics of sharing, community living and inclusiveness. Jesus lived a life of selfless service and was endowed with supernatural capacities which were oriented for the welfare of the less fortunate ones in the society. Despite his enormous influence and power, he lived a simple and poor life and in humble service to humanity. In his last supper, although being their master, he washed the feet of his disciples and asked them to “do this in my memory” – that is, to embrace one another in love, service and humility. -

The Gay Revolution and the Pink Flamingos Bachelor’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jiří Vrbas The Gay Revolution and the Pink Flamingos Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. Michael Matthew Kaylor, PhD. 2016 1 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ………………………………………………. 2 “I thank God I was raised Catholic, so sex will always be dirty.” (John Waters) Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor doc. Michael Matthew Kaylor, PhD, for his help and for making me believe in this topic. I would also like to thank him and Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, BA, alike for their Gay Studies course. Knowledge acquired in their class provided the necessary background for this analysis. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 I. Being Gay in the Past .................................................................................................. 7 I.1. 18th Century Europe ................................................................................................ 7 I.2. The Early 20th Century USA .................................................................................. 9 I.3. The 1950s USA .................................................................................................... 14 II. Early Gay Rights Activism .................................................................................... -

John Waters (Writer/Director)

John Waters (Writer/Director) Born in Baltimore, MD in 1946, John Waters was drawn to movies at an early age, particularly exploitation movies with lurid ad campaigns. He subscribed to Variety at the age of twelve, absorbing the magazine's factual information and its lexicon of insider lingo. This early education would prove useful as the future director began his career giving puppet shows for children's birthday parties. As a teen-ager, Waters began making 8-mm underground movies influenced by the likes of Jean-Luc Godard, Walt Disney, Andy Warhol, Russ Meyer, Ingmar Bergman, and Herschell Gordon Lewis. Using Baltimore, which he fondly dubbed the "Hairdo Capitol of the World," as the setting for all his films, Waters assembled a cast of ensemble players, mostly native Baltimoreans and friends of long standing: Divine, David Lochary, Mary Vivian Pearce, Mink Stole and Edith Massey. Waters also established lasting relationships with key production people, such as production designer Vincent Peranio, costume designer Van Smith, and casting director Pat Moran, helping to give his films that trademark Waters "look." Waters made his first film, an 8-mm short, Hag in a Black Leather Jacket in 1964, starring Mary Vivian Pearce. Waters followed with Roman Candles in 1966, the first of his films to star Divine and Mink Stole. In 1967, he made his first 16-mm film with Eat Your Makeup, the story of a deranged governess and her lover who kidnap fashion models and force them to model themselves to death. Mondo Trasho, Waters' first feature length film, was completed in 1969 despite the fact that the production ground to a halt when the director and two actors were arrested for "participating in a misdemeanor, to wit: indecent exposure." In 1970, Waters completed what he described as his first "celluloid atrocity," Multiple Maniacs. -

ੴ ੴ the Sikh Bulletin

The Sikh Bulletin ਅੱਸੂ-ਪੋਹ ੫੫੨ ਨਾਨਕਸ਼ਾਹੀ October‐December 2020 ੴ ਸਿਤ ਨਾਮੁ ਕਰਤਾ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਿਨਰਭਉ ਿਨਰਵੈਰੁ ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਿਤ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੈਭੰ ਗੁਰ ਪਸਾਿਦ ॥ dfdss Ik oaʼnkār saṯ nām karṯā purakẖ nirbẖao nirvair akāl mūraṯ ajūnī saibẖaʼn gur parsāḏ. ੴ ੴ THE SIKH BULLETIN www.sikhbulletin.com [email protected] Volume 22 Number 4 Published by: Hardev Singh Shergill 100 Englehart Drive, Folsom, CA 95630 USA Tel: (916) 933‐5808 In This Issue / ਤਤਕਰਾ Editorial Editorial…………………………………..………….……..1 Gurbani Shabd Vichar Hitting the Target but Missing the Point. Karminder Singh Dhillon PhD …………..…..3 The Concept of MAYA in Indian Philosophy When it comes to the Sikh leadership and matters concerning and Sikh Religion Sikhs – the target is always the same: arouse anger amongst the Sikh Professor Hardev Singh Virk, PhD….……11 masses and bring them to the streets for a dharna, protest, morcha ਗੁਰ ੂ ਤੇਗ ਬਹਾਦਰ ਸਗਲ ਿਸਸਟ ਕੀ ਚਾਦਰ or march. The Sikh masses have never failed to oblige. They have ਗੁਰਚਰਨ ਿਸੰਘ ਿਜਉਣ ਵਾਲਾ……………..…………19 thrown their support in large numbers; suffered the consequences ranging from a police beating to arrests, hospitalization, economic Interview with Renowned Pharmacologist, hardships; and paid a heavy price, including death – only to realize Neuroscientist and Eminent Scholar of Sikhism Bhai Dr. Harbans Lal the sacrifices were mostly in vain. Dr. Devinder Pal Singh…………...……..22 The objective of the Sikh leadership is also always the same: divert attention from the real issues, pursue personal agendas, pose Natural Philosophers ‐ Nanak is at the Top of the List as champions of the community and ensure that their positions Prof Devinder Singh Chahal, PhD……….27 remain secure. -

'I'm SO FUCKING BEAUTIFUL I CAN't STAND IT MYSELF': Female Trouble, Glamorous Abjection, and Divine's Transgressive Pe

CUJAH MENU ‘I’M SO FUCKING BEAUTIFUL I CAN’T STAND IT MYSELF’: Female Trouble, Glamorous Abjection, and Divine’s Transgressive Performance Paisley V. Sim Emerging from the economically depressed and culturally barren suburbs of Baltimore, Maryland in the early 1960s, director John Waters realizes flms that bridge a fascination with high and low culture – delving into the putrid realities of trash. Beginning with short experimental flms Hag in a Black Leather Jacket (1964), Roman Candles (1966), and Eat Your Makeup (1968), the early flms of John Waters showcase the licentious, violent, debased and erotic imagination of a small community of self-identifed degenerates – the Dreamlanders. Working with a nominal budget and resources, Waters wrote, directed and produced flms to expose the fetid underbelly of abject American identities. His style came into full force in the early 1970s with his ‘Trash Trio’: Multiple Maniacs (1970), Pink Flamingos (1972), and Female Trouble (1974). At the heart of Waters’ cinematic achievements was his creation, muse, and star: Divine.1 Divine was “’created’ in the late sixties – by the King of Sleaze John Waters and Ugly-Expert [makeup artist] Van Smith – as the epitome of excess and vulgari- ty”2. Early performances presented audiences with a “vividly intricate web of shame, defance, abjection, trauma, glamour, and divinity that is responsible for the profoundly moving quality of Divine as a persona.”3 This persona and the garish aesthetic cultivated by Van Smith aforded Waters an ideal performative vehicle to explore a world of trash. Despite being met with a mix of critical condemnation and aversion which relegated these flms to the extreme periph- ery of the art world, this trio of flms laid the foundation for the cinematic body of work Waters went on to fesh out in the coming four decades. -

Pink Flamingoes and the Culture of Trash

--�·. : ··-·,----., ,•' ! \··I Sleaze queen Divine in Pink Flamingos. 808 THE TERRAINOF THE UNSPEAKABLE Pink Flamingos and the culture of trash DARREN TOFTS To me, bad rasre is whar enrertainmenc is all about. If someone vomits watching one of my films, it's like getting a standing ovation. John Waters 1 Theorizing crash culture presents cultural studies with some awk ward problems. The issue is not just che way crash culture rends co posicion irs audience with respect co gender and sexual policies. Ir is also chat rhe rerm is used both descriptively and normatively: ir designates a range of subcultural practices, but it also suggests a moral accirude , a cultural discourse on what is acceptable as representation - a discourse char emerged in overt confrontation wirh the guardians of high culture. In recent years the rerm has been used in rhe context of a continuing and increasingly sophisticated interest in che obscene, and also of a sustained intellectual inquiry inco rhe dynamics of populism and mass culture, and the conditions of production and consumption in post-industrial society. Within cultural studies there has been a rigorous critique of the ways in which crash culture has come co be understood, how it is used and by whom, and the ambiguous policical force it exerts within the domain of popular culture generally. Philip Brophy has distinguished between che rerm crash- ('all maccer of refuse ... all the material lefr over') and its erstwhile synonym, junk ('all rhe material injected, invited, avowed, support ed'), in cerms of their relation co the process of consumption (culture). Brophy's collaborative 'Trash and Junk Culture' exhibi tion of 19892 skilfully represented the extensive and hierarchical nature of crash culture, from the overtly visible (exploitation advertising, video nascies, pornograph�·) to che sublim�nal (body building and wresding magazines). -

Politics and Religion: the Need for an Overlapping Consensus

Politics and Religion: The Need for an Overlapping Consensus (an exemplar from the Hindu tradition) A.D.J. Desai Submitted for the degree of PhD. 1 ABSTRACT Politics and Religion: The Need for an Overlapping Consensus (an exemplar from the Hindu Tradition) This Thesis examines the consensus Hinduism in India shares with the ideology of liberal pluralism, and applies these reflections to religious education in the English context. The Rawlsian theory of justice models the political structure of a liberal plural society. Insights from communitarianism, relativism and Alasdair Maclntyre, are critically assessed and used to enlarge this model. Further, Carol Gilligan and Tom Kitwood emphasise that moral citizens in a plural society need, and must provide, a caring and open environment. The overlapping consensus across liberal pluralism and the Hindu tradition is assessed at the (i) theological and (ii) empirical levels. (i) Vedantic concepts are formulated to highlight a potentially strong consensus across Vedantic and liberal viewpoints. The presentation of God as a caring and egalitarian mother is emphasised. (ii) A landscape survey (sample size 550) was conducted to help focus the case-study investigations. Case-studies of four Indian young Hindus studied attitudes towards pluralism through discussions on Ayodhya 1992. The minute sample size of the case- study meant that this data could not, in itself, justify inductive generalisation. Nevertheless, the case-studies did highlight some important and disconcerting voices, and did not contradict the conclusions from the larger landscape survey. The data warns that contemporary sentiment may be incongruent with the potentially strong consensus across liberal pluralism and Vedantic theology. -

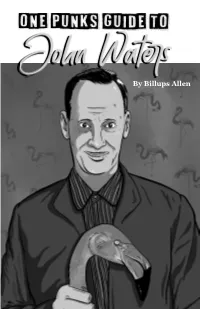

By Billups Allen Billups Allen Spent His Formative Years in and Around the Washington D.C

By Billups Allen Billups Allen spent his formative years in and around the Washington D.C. punk scene. He graduated from the University of Arizona with a creative writing major and a film minor. He has worked in seven different record stores around the country and currently lives in Memphis, Tennessee where he works for Goner Records, publishes Cramhole zine, contributes music and movie writing regularly to Razorcake, Ugly Things, and Lunchmeat magazines, and writes fiction. (cramholezine.com, [email protected]) Illustrations by Codey Richards, an illustrator, motion designer, and painter. He graduated from the University of Alabama in 2009 with a BFA in Graphic Design and Printmaking. His career began by creating album art and posters for local Birmingham venues and bands. His appreciation of classic analog printing and advertising can be found as a common theme in his work. He currently works and resides at his home studio in Birmingham, Alabama. (@codeyrichardsart, codeyrichards.com) Layout by Todd Taylor, co-founder and Executive Director of Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. This zine is made possible in part by support by the Los Angeles County Department of Arts and Culture. Printing Courtesy of Razorcake Press razorcake.org ne rainy weekday, my friend and I went to a small Baltimore shop specializing in mid-century antiques called Hampden Junque. -

Meeting Divine: a “Hairspray” Story As Told by Jerry Stiller

The Academy Follow We are The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences and we champion the power of human imagination. Jul 27 · 6 min read Divine and Jerry Stiller in “Hairspray” (1988) Meeting Divine: A “Hairspray” Story As told by Jerry Stiller In honor of Hairspray’s 30th anniversary, the Academy hosted a reunion with the cast and crew, hosted by Barry Jenkins. Below is Jerry Stiller’s recollection of the relationships he built while working on the lm. In 1988, I was asked to play a role in Hairspray, which was lming in Baltimore, director John Waters’ hometown. Sonny Bono and Deborah Harry were also in the lm. I agreed to do Wilbur Turnblad, the husband of Divine. Pia Zadora played a ‘60s beatnik and Ricki Lake played my daughter. The word “crossover lm” was heard in the industry. The script had all the makings of a sleeper. John Waters introduced himself. He was then 41 years old. He joked about his pencil-thin mustache. “I think I saw it on some actor in a B- movie and decided to try it,” he told me. He was funny; I liked him. I’d chosen to be here, in a John Waters movie. It was like nothing I’d ever done. “You’ll have fun,” John said. “See you on the set.” I was getting into costume and makeup when I met Glenn Milstead, known as Divine, for the rst time. He too was getting ready to shoot our rst scene. He was wearing a housedress and adjusting his wig. -

Chapter-V Artha As a Value Concept

151 Chapter-V Artha as a Value Concept The term 'artha' refers to both the wealth and the political economy and as such covers both the economic and the political values. All value-theories and theories of normative ethics are centered round the concept of human self and his desires and interests. All ofthem can be brought under the head of Kama. Hence, in the words of Prof. Hiriyanna, 'They, Artha and Kama are the useful and agreeable and represent the lower values." Before dealing with the Artha- value proper, it will be better to deal with the Vedic outlook on life and the world. The Vedic outlook on life is integral and comprehensive. Even the literal meaning of the Vedic hymns shows that the Vedic people were interested both in secular as well as spiritual values, both in the individual as well as social reality. Theirs was not an other-worldly and escapist religion. There is no place for pessimistic trends like that of Schopenhauer in Vedic philosophy and religion. Unlike Schopenhauer and other pessimists, the Vedic people prayed for a life span of hundred years and even more. According to Schopenhauer, it is impossible for a man to be completely happy and, hence, ·in the mood of extreme pessimism, he becomes an advocate of the will to die. On the contrary, the Vedic people were advocates of the will to live and the will to conquer. They appear to be very cheerful and heroic in their lives ordinarily beset with obstacle~ and struggles. In leading a cheerful and heroic life, they would not be depressed.