The Chelsea Pietà

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACP Spire May2019.Pdf

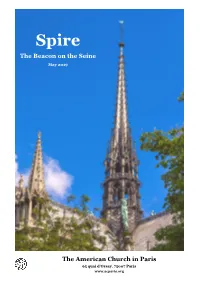

Spire The Beacon on the Seine May 2019 The American Church in Paris 65 quai d’Orsay, 75007 Paris www.acparis.org Please help recycle this publication. When you’re through reading it, instead of tossing it in the bin, return it to the Welcome desk or Foyer. In this issue Thoughts from The Rev. Dr. Scott Herr 3 Bible readings for May 4 Spring retreat at Abbaye-Fleury, by Rev. Tim Vance 5 Prayer ministry, by TL Valluy 6 Notre Dame, by Rebecca Brite 7 Alpha success, by Lisa Prevett 9 Body of Christ: What’s up in Paris, by MaryClaire King 10 What’s up in Paris: May event listings, by Karen Albrecht 11 Sunday Atelier Concert Series, by Fred Gramann 12 Silence: The Christian stranger in Japan, by David Jolly 13 Recipe for a successful Easter breakfast, by Mary Hovind 14 The AFCU meets in Paris 15 ACP Taizé Thursdays, by Julia Metcalf 17 ACP Youth Program Concerts, by Sara Barton 19 The Nabis and decoration, by Karen Marin 21 May ACP calendar, by John Newman 22-23 ACP volunteer opportunities 23 The spire of the Notre Dame, as it was. Note the rescued rooster (the so-called “spiritual lightning rod”) and the bronze statues of the apostles, including that of Thomas the Apostle (his back to the viewer), with the features of restorer Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Read more in our story on page 7. Photo: ©CreativeMarket 2 ACP Spire, May 2019 Thoughts from The Rev. Dr. Scott Herr Senior Pastor Dear Members and Friends of the ACP, Grace, mercy and peace response recognizing that although we are a different “part” to you in these first weeks of the holy catholic Church, nevertheless we are brothers of Eastertide. -

Un Musée Révolutionnaire Le Musée Des Monuments Français D’Alexandre Lenoir

Un Musée révolutionnaire Le musée des Monuments français d’Alexandre Lenoir Musée du Louvre Églises St-Eustache / St-Roch / St-Sulpice Le musée des Monuments français, The Museum of French Monuments, aujourd’hui tombé dans l’oubli, connut now forgotten, had during the French sous la Révolution française un destin Revolution an exceptional destiny. exceptionnel. Located close to Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Situé non loin de Saint-Germain-des-Prés, in the convent of the Petits-Augustins, dans le couvent des Petits-Augustins, le musée ouvre ses portes en 1795 grâce the museum opens its doors in 1795 thanks à l’engagement d’un jeune peintre. to the commitment of a young painter. Soucieux de préserver les œuvres As he wanted to preserve the confiscated saisies dans les églises, suite à artworks in churches, Alexandre Lenoir la confiscation des biens du clergé, (1761-1839) contributed to preserve many Alexandre Lenoir (1761-1839) contribue tombs and statues. The exhibition, in a à préserver de nombreux tombeaux et chronological, scientific and romantic course, statues de culte. La présentation knew a huge success with the public from all de ces vestiges, selon un parcours over Europe. chronologique, savant et romantique, connait un immense succès auprès At the closing of the museum in 1816, its du public qui accourt de toute l’Europe pour le visiter. collections are scattered: artworks are sent to the Louvre or are replaced in the churches of À la fermeture du musée en 1816, ses Paris. Some find their original building, others, collections sont dispersées : les œuvres often after the destruction of their monastery sont envoyées au Musée du Louvre ou or church, are assigned to remaining places. -

Cover Hubert Le Sueur Hercules and Telephus.Indd

benjamin proust fine art limited london benjamin proust fine art limited london attributed to HUBERT LE SUEUR Paris, 1580–1658 hercules and telephus circa 1630 Bronze 39.4 x 15.9 x 12.4 cm Inventory mark ‘8’ in red paint on lion skin tail provenance Most probably, François Le Vau (1613–1676), ‘Maison du Centaure’, 45 Quai de Bourbon, Paris, until his death; Most probably, Louis, Grand Dauphin de France (1661–1711), Château de Versailles, from at least 1689 and until his death, when sold; Most probably, Jean-Baptiste, Count du Barry (1723–1794), Paris; His sale, 21 November 1774, lot 142; Noble private collection, Provence, France, until 2017 comparative literature F. Souchal, Les Frères Coustou, Paris, 1980 G. Bresc-Bautier, ‘L’activité parisienne d’Hubert Le Sueur sculpteur du roi (connu de 1596 à 1658)’, in Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français, 1985, pp. 35–54 C. Avery, ‘Hubert Le Sueur, the ‘Unworthy Praxiteles’ of King Charles I’, in Studies in European Sculpture II, London, 1988, pp. 145–235 J. Chlibec, ‘Small Italian Renaissance Bronzes in the Collection of the National Gallery in Prague’, in Bulletin of the National Gallery in Prague, III-IV (1993–94), pp. 36–52 A. Gallottini (ed.), ‘Philippe Thomassin: Antiquarum Statuarum Urbis Romae Liber Primus (1610–1622)’, in Bollettino d’Arte, 1995, pp. 21–23 S. Castelluccio, ‘La Collection de bronzes du Grand Dauphin’, in Curiosité: Édutes d’histoire de l’art en l’honneur d’Antoine Schnapper, Paris, 1998, pp. 355–63 S. Baratte, G. Bresc-Bautier et al., Les Bronzes de la Couronne, exh. -

Modèle Parc À Imprimer

1 Porte du Parc et maison forestière du parc. Elles représentent le dieu Neptune domptant un cheval marin qu’il menace de son trident et Amphitrite, son épouse, qui 2 Bosquet du Levant et Vase couronné de fl eurs apparaît ici chevauchant un dauphin et accompagnée de trois petits tritons. 3 Pavillon Présidentiel Aménagé dans une partie des anciens communs du château, ce 9 Théâtre de Bacchus et statue de Diane à la biche bâtiment servit de pavillon de chasse jusqu’en 1995. Le bosquet de Bacchus était parallèle à celui de Diane qui se situait, symétriquement, de l’autre côté de la rivière. Il était agrémenté 4 Pavillon des gardes, toilettes publiques. d’un bassin en miroir animé d’une gerbe. Il fut comblé par la suite et Marie-Antoinette y fi t installer un théâtre de bois. Aujourd’hui 5 Socle des Pavillons des Invités une statue de Diane orne son centre. Douze pavillons s’étendaient depuis le château vers l’Abreuvoir. Ils accueillaient les invités du Roi, l’un deux servait de "pavillon 10 Le Tapis Vert des bains" et deux autres renfermaient les fameux Globes de Autrefois cascade, 52 marches s’étageaient sur près de 200 mètres Coronelli. Disposés de part et d’autre du grand miroir, ils étaient de long. Louis XIV en était très fi er et la fi t recouvrir de marbres reliés entre eux par des treillages de verdure. de différentes couleurs. Il commanda deux groupes de statues pour l’ornementer : en haut la Seine et la Marne de Coysevox, 6 Socle du château, statues des Coureurs. -

Bancs-Et-Statues.Pdf

1 PartieDevenez — Titrage plus Mécène ou moins long du patrimoine titre2011 rubrique Adoptez Contacts une statue ou un banc Serena Gavazzi Chef du service mécénat des jardins de Versailles et Marly Tél : 01 30 83 77 04 / 06 74 00 81 71 [email protected] Jeanne Bouhey Responsable projets mécénat Tél : 01 30 83 77 70 [email protected] 2 un patrimoine d'exception 3 LES JArDINS DE VErSAILLES ET MArLY LES JArDINS DE VErSAILLES : UN MUSÉE DE SCULPTUrE EN PLEIN AIr Véritable architecture végétale prolongeant les lignes et les perspectives du Château, les jardins de Versailles voulus par Louis XIV et créés par Le Nôtre visent à réunir l’art et la nature. L’ampleur des proportions, la nouveauté et la variété des effets et des points de vue ainsi que la qualité des ornements en font un lieu unique au monde. La statuaire et l’eau sous toutes ses formes, jaillissante, cascadante ou calme reflet de la lumière, animent les Jardins. Ils abritent la plus importante collection de sculptures du XVIIe siècle. Vases, groupes sculptés, statues, termes, bustes, antiques ou œuvres des plus grands artistes de l’époque – Tuby, Girardon, Coysevox, Marsy – entraînent les millions de visiteurs qui chaque année parcourent les jardins dans un véritable périple poétique, sur fond de mythologie et d’humanisme. Mis en place sous Louis XIV, ce décor n’a presque pas été remanié depuis sa conception d’origine. On compte 221 œuvres pour les jardins du Château, 32 pour ceux de Trianon. Du parterre de Latone à celui d’Apollon, de l’Orangerie au bosquet de la Reine, jusqu’à Trianon, dieux, héros de la mythologie et de l’histoire côtoient les figures allégoriques représentant les tempéraments de l’homme, les genres poétiques, les saisons et les continents. -

Nouvelle Présentation Des Salles Louis Xiv

nouvelle présentation des salles louis xiv à partir du 4 mai 2019 Versailles, le 2 mai 2019 Communiqué de presse À partir du 4 mai 2019, le château de Versailles propose à ses visiteurs une nouvelle présentation des salles Louis XIV retraçant le règne du souverain. Dans un parcours totalement repensé associant une approche chronologique et thématique, certains des chefs-d’œuvre des collections dialoguent avec des œuvres méconnues issues des réserves et d'autres récemment acquises ou restaurées. Ce parcours à travers le XVIIe siècle permet aussi de renouveler le regard porté sur les collections. – en buste, de trois-quarts, en pied, intime, officiel ou travesti. Certaines des œuvres présentées comptent parmi les créations majeures de Le Brun, de Mignard, de Van der Meulen, de Largillière ou de Coysevox ; d’autres ont été créées par de petits maîtres et témoignent de la richesse de la création artistique au XVIIe siècle. Le public découvrira certaines des dernières acquisitions, telles que La famille royale autour du berceau du duc d’Anjou de Charles Le Brun, les quatre petits portraits de Louis Elle le Père, celui de Tiberio Fiorilli, dit Scaramouche de Pietro Paolini ou encore La Sculpture travaillant au buste de Louis XIV de Baudrin Yvart et La Fondation de l’hôtel des Invalides en 1674 de Pierre Dulin. château de Versailles / Thomas Garnier Garnier / Thomas Versailles de château © Les salles Louis XIV permettent aussi de rassembler quelques pièces de mobilier provenant d’emplacements Situées au premier étage de l'Aile du Nord du château aujourd'hui disparus comme le médaillier du Cabinet les salles Louis XIV évoquent au travers d'une enfilade des Raretés de Louis XIV. -

Visite À Notre-Dame De Paris

9 Avril 2013 Visite à Notre-Dame de Paris Plan de Paris 1630 A l’occasion du 850ème anniversaire de Notre-Dame, nous avons pu bénéficier d’une conférence sur l’architecte intérieure de Notre-Dame Christine, Gilberte, Nine, Nelly, Sabine, Stéphanie, Thérèse et Pierre ont souhaité la bienvenue à deux nouvelles adhérentes : Eveline et Enissa La pluie nous empêchant de sortir, c’est sur photos, que notre conférencière de l’Association C.A.S.A., nous explique : - née de la vision grandiose de Maurice de Sully évêque de Paris sous Louis VII, le pape Alexandre III, posent – au printemps 1163 - la première pierre de Notre-Dame de Paris sur la place de la vénérable basilique constantinienne Saint-Etienne, sur le modèle de la basilique de Saint Denis. Elle fut consacrée en 1182 en présence de Philippe II. La cathédrale a vécu au rythme de grandes heures du royaume comme de ses misères, de processions royales au sacre de l’empereur, de Te Deum au culte de la déesse Raison, de la restauration de Viollet-le-Duc à l’installation des nouvelles cloches du jubilé ; - le sens de la cathédrale orientée Est-Ouest, comme le soleil au Levant qui nous irradie de sa lumière - Jésus ressuscité au matin de Pâques étant lumière pour notre monde ; - - Les détails de la façade et de ses dimensions de la forme symbolique du carré au cœur duquel la rosace est dédiée à La Vierge ; - - La rangée de Rois non pas de France mais de la Bible, étêtés pendant la révolution et restaurés par Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) ; 1 Portail du Jugement Dernier Portail de la Vierge Portail Sainte Anne - les 3 portails aux sculptures multiples de gauche à droite, le portail de la Vierge, celui du Jugement dernier et le portail Sainte-Anne. -

What Copying Meant to Cézanne

The Japanese Society for Aesthetics Aesthetics No.21 (2018): 111-125 What Copying Meant to Cézanne NAGAЇ Takanori Kyoto Institute of Technology, Kyoto Introduction Did copying hold particular meaning for Paul Cézanne (1839-1906)? Determined to become a painter, Cézanne set off for Paris in 1861. There he made drawings of the human form at the private Académie Suisse, and began to make copies of the artworks of the past at such museums as the Louvre. He took the entrance exam for the national art academy but failed. Though he gave up on that exam, he entered a succession of paintings in the government-sponsored Salons of 1866, 1867, 1868, 1869, 1870, 1872, 1878, 1879 and 1881, each rejected because they did not fit the Neoclassicist trend then controlling the Salon. [1] After the Salon was privatized in 1881, he finally had a work accepted in 1882 as the student of his friend Antoine Guillemet (1843-1918), but then lost interest in the Salon and did not enter any other works. But this did not mean that Cézanne ignored classic paintings.[2] In a process that continued into his later years, Cézanne created numerous copy drawings of works at the Musée du Luxembourg, the contemporary art museum of the period, and of the works of the past assembled at the Louvre and the Comparative Sculpture Museum in the Trocadéro, thus indicating that he maintained a strong interest in the great artists of his own period and of the past. Cézanne received official permission to make copies in the Louvre on November 20, 1863, and on April 19, 1864 he made a copy of Et in Arcadia Ego (fig. -

Sauvegarde Des Statues Des Frères Coustou Au Musée Des Beaux-Arts De Lyon

SAUVEGARDE DES STATUES DES FRÈRES COUSTOU AU MUSÉE DES BEAUX-ARTS DE LYON DOSSIER DE PRESSE 23 MARS 2021 LE SAUVETAGE INDISPENSABLE DES STATUES DES FRÈRES COUSTOU Dans le cadre de la 4e Convention patrimoine comprendra le dépoussiérage des deux œuvres, 2019-2024 signée le 6 décembre 2019, l’État et leur décrassage, l’élimination des graffiti, des la Ville de Lyon ont souhaité associer leurs inscriptions et des autocollants, mais aussi celle moyens financiers et leurs compétences, pour des produits de leur corrosion, et, enfin, la pro- restaurer les sculptures des frères Coustou tection de leur surface. Elle aura lieu dans une représentant la Saône et le Rhône. structure aménagée à cette fin dans le cloître du Situées sur la place Bellecour, au pied de la statue musée des Beaux-Arts. Plusieurs présentations équestre de Louis XIV, les deux chefs-d’œuvre, de cette opération exceptionnelle seront effec- dans un état critique, ont été déplacés au musée tuées au mois de juin 2021 par les restaurateurs des Beaux-Arts de Lyon où ils seront restaurés. pour des groupes et sur réservation. Ces bronzes de 1721, classés au titre des monu- À l’issue de leur restauration, à l’automne 2021, ments historiques, sont les derniers de cette les deux bronzes des frères Coustou seront époque encore exposés en extérieur en France. visibles par le public de manière permanente, À ce jour, aucun dispositif ne les protège des au sein du musée des Beaux-Arts, au bas de l’escalier dégradations. Les œuvres sont également expo- d’honneur de l’abbaye des Dames de Saint-Pierre, sées aux intempéries et à la pollution atmos- dit également « escalier Thomas Blanchet ». -

France : Notre-Dame De Paris, Mille Ans D'histoire

France : Notre-Dame de Paris, mille ans d'histoire HEMIS_3502345 France, Paris (75), zone classée Patrimoine Mondial de l'UNESCO, l'île de la Cité, la Cathédrale Notre-Dame (vue aérienne) Page 1/35 La cathédrale contenait un patrimoine historique d'une richesse exceptionnelle qui faisait de cette " Vieille Dame " un musée de l'histoire religieuse au travers des siècles.. Nous avons tenté de rassembler en images, une histoire presque millénaire, parsemée d'oeuvres d'art, de reliques et de pièces majeures, et de constructions défiant la gravité. Vous découvrirez également, vu du ciel, le toit dans toute son ampleur et les détails de la flèche aujourd'hui disparus. La catastrophe passée, notre devoir de mémoire est de ne rien oublier et laissons place le plus vite possible aux artisans bâtisseurs. Page 2/35 HEMIS_3496709 HEMIS_3497977 France, Paris (75), zone classée Patrimoine Mondial de l'UNESCO, la cathédrale France, Paris (75), zone classée Patrimoine Mondial de l'UNESCO, Ile de la Cité, Notre-Dame sur l'Île de la Cité (vue aérienne) cathédrale Notre-Dame, La sainte couronne d'épines portée par Jésus C[..] HEMIS_3495528 HEMIS_3497994 France, Paris (75), zone classée Patrimoine Mondial de l'UNESCO, île de la cité, France, Paris (75), zone classée Patrimoine Mondial de l'UNESCO, Ile de la Cité, cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, charpente cathédrale Notre-Dame, détail de la flèche Page 3/35 HEMIS_3497913 HEMIS_3497917 France, Paris (75), zone classée Patrimoine Mondial de l'UNESCO, île de la Cité, la France, Paris (75), zone classée Patrimoine -

Versailles: Art, Power, Resistance and the Sun King's Palace

Versailles: Art, Power, Resistance and the Sun King’s Palace (Spring 2020) SYLLABUS: SIGN 26043, FREN 26043 Professor Larry Norman: [email protected] (Office hours T 10:30-noon) Course Assistant (CA): Amine Bouhayat: [email protected]. Language Assistant (LA): Peadar Kavanagh: [email protected] INTRODUCTION: ART AND POWER IN THE 17TH AND 21ST CENTURIES April 7 Introduction April 9 ◊ Colin Jones, Versailles (Introduction, chapter 1) ◊ Peter Burke, The Fabrication of Louis XIV (1992, chapters 1 and 2) ◊ France in the World, chapter “1682: Versailles, Capital of French Europe” (2017, 2019, ed. P. Boucheron) ◊ Consult sites: http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/key- dates/party-delights-enchanted-island https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p03w3y8m https://www.artforum.com/print/201103/contemporary-art-at-versailles-27579 I. MOLIÈRE: SATIRE, MONARCHY, AND SOCIETY April 14 ◊ Molière, Tartuffe (1664-1669) April 16 ◊ Molière, Tartuffe and Molière’s preface & Petitions to King (Canvas) ◊ France in the World, chapter “1685: France Revokes the Edict of Nantes” (in same document as “1682” assigned April 9) April 21 ◊ Molière, The Would-Be Gentleman (Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, 1668, English text on canvas) ◊ Colin Jones, Versailles, chapter 4, “Living: Styles of Versailles Life”) April 23 ◊ Molière, The Would-Be Gentleman ◊ La Bruyère, Characters (1693), “Of the Court” (with special attention to numbers 2, 19, 32, 62-64, 74-75, 100-101) ◊ Saint Simon, Memoirs (1715) —English read pp. 245-266; —French read pp. 469-70, 478-486, 521-536 ◊ Mme de Sévigné, Letters (“Gaming at Versailles, 1676”) Presentation by Peadar Kavanagh II. RACINE: POLITICAL TRAGEDY, ANCIENT AND MODERN April 28 ◊ Racine, Iphigenia and preface (1674) April 30 ◊ Racine, Iphigenia (1674) ◊ Édouard Pommier, “Versailles: The Image of the Sovereign” (1998) April 31 (Noon) Midterm Paper Proposal due (1 Page, to Prof. -

THE LOUVRE Uniform with This Volume the NATIONAL GALLERY by J

National Treasures THE LOUVRE Uniform with this volume THE NATIONAL GALLERY BY J. E. CRAWFORD FLITCH Other hooks are in preparation THE LOUVRE BY E. E. RICHARDS BOSTON SMALL, MAYNARD AND COMPANY PUBLISHERS PRINTED P.Y THE RIVERSIDE PRESS LIMITED EDINBURGH T9I2 CONTENTS PAGE I. THE PALACE OF THE LOUVRE . 11 II. THE MUSEUM OF THE LOUVRE . 6l III. THE PAINTINGS ..... 74 IV. THE GREEK AND ROMAN SCULPTURES . 110 V. MEDIAEVAL, RENAISSANCE AND MODERN SCULPTURE . .132 VI. THE EGYPTIAN AND ASIATIC ANTIQUITIES 140 VII. THE ANTIQUE PAINTINGS, POTTERIES, BRONZES AND ORNAMENTS . 149 VIII. THE IVORIES, ENAMELS, FURNITURE AND FAIENCE . .156 IX. THE MUSEE DE MARINE, THE MUSEE CHINOISE, THE COLLECTION GRAN- DIDIER, AND THE CHALCOGRAPHIE . ] 69 7 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS LA DANCE . {Carpeanx) Frontispiece Photograph '. A linari TO FACE PAGE THE LOUVRE OF THE XV. CENTURY 32 THE GRANDE . (Galerie) 33 THE LOUVRE FROM THE RIVER 48 6 PERRAULT'S COLONNADE ' 49 ELIZABETH D'AUTRICHE . {Clonet) . 56 REPAS DES PAYSANS {Lenain) 57 Photograph'. A linari GlLLES {IVat lean) . 64 Photograph'. A linari LE CHATEAU DE CARTES (Chardin) 6.5 Photograph'. A linari MADAME RECAMIER . {David) . 72 L'IMPERATRICE JOSEPHINE {Pi-ltd'lion) 73 Photograph'. A linari PAYSAGE . {Corot) . 80 Photograph: A linari L'ANGELUS . {Millet) . 81 OLYMPIA {Manet) . 88 Photograph '. Giraudon PORTRAIT D'UN VIEILLARD ET DE SON PETITS- FILS . {Ghirlandaio) , 89 9 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS TO FACE PAGE ANTIOPE .... {Correggio) . 96 Photograph: Alinari ALPHONSE DE FERRARA ET LAURA DE DlANTI (Titian) . 97 Photograph: A linari CONCERT CHAMPETRE . (Giorgione) 104 FERDINARD D'ARPAGON (Theotocofiuh) 105 Photograph: A linari LE PIED-BOT (Kibera) .