Forming the Bogeyman in the Pied Piper, Peter Pan, and the Ted Bundy Tapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bogeyman Show Notes Season 1, Episode 6

The Bogeyman Show Notes Season 1, Episode 6 Welcome to episode six of the Time Pieces History Podcast. I can’t believe we’re halfway through the first season already! I decided we’d have some light relief today, and look at the legend of the bogeyman. This creature pops up around the world, not just in Britain, but he’s certainly significant. As part of my Time Pieces History Project I looked at some of my favourite books, so this episode is inspired by that, and in particular Raymond Briggs’ Fungus the Bogeyman, a family man who has questions about his life. If you haven’t read Fungus, I highly recommend getting yourself a copy. Briggs is probably more famous for his books The Snowman and Father Christmas, but I always preferred Fungus, perhaps because of Briggs’ lovingly-drawn illustrations of his underground world. It’s also full of puns and funny inventions, which made me laugh rereading it as an adult. Bogeymen like things damp and mouldy, and keep their clothes in a ‘waterobe.’ In private they’re polite and softly-spoken, and like to go to art galleries, where they get emotional over the paintings. Fungus’ day job though (or should that be night job?) is the more traditional bogeyman role, of scaring children, disturbing people’s sleep and turning milk sour. Over several pages, we see Fungus wondering if there should be more to his existence than traumatising humans, in scenes which are both hilarious and sad. Raymond Briggs put his own spin on the legend of the bogeyman, which is fine, because one good thing about them is that there’s no hard and fast rule on what one looks like, or what they do. -

DIANA PATON & MAARIT FORDE, Editors

diana paton & maarit forde, editors ObeahThe Politics of Caribbean and Religion and Healing Other Powers Obeah and Other Powers The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing diana paton & maarit forde, editors duke university press durham & london 2012 ∫ 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Katy Clove Typeset in Arno Pro by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Newcastle University, which provided funds toward the production of this book. Foreword erna brodber One afternoon when I was six and in standard 2, sitting quietly while the teacher, Mr. Grant, wrote our assignment on the blackboard, I heard a girl scream as if she were frightened. Mr. Grant must have heard it, too, for he turned as if to see whether that frightened scream had come from one of us, his charges. My classmates looked at me. Which wasn’t strange: I had a reputation for knowing the answer. They must have thought I would know about the scream. As it happened, all I could think about was how strange, just at the time when I needed it, the girl had screamed. I had been swimming through the clouds, unwillingly connected to a small party of adults who were purposefully going somewhere, a destination I sud- denly sensed meant danger for me. Naturally I didn’t want to go any further with them, but I didn’t know how to communicate this to adults and ones intent on doing me harm. -

Fairy Tale Versions~

FAIRY TALES/FOLK TALES Fairy Tales are a type of folktale in which magic plays a great part. Compiled by Sheila Kirven GENERAL Anderson, Hans Christian Steadfast Tin Soldier Juv.A544ste Armstrong, Gerry The magic bagpipe Juv. 788.9 .A735m Browne, Anthony Into the Forest Juv. B882i (Story incorporates elements of familiar tales) Casserley, Anne Roseen Juv. 398.21 .C344r Chapman, Gaynor The Luck Child Juv. 398.21.C466l 1968 De Regniers, Beatrice Little Sister and the Month Brothers Juv. D431Li Schenk The House in the Wood and Other Old Fairy Stories Juv. 398.2.G864h Little Lit: Folklore and Fairy Tale Funnies Juv.398.21.F666 Hennessy, B. G. Once Upon a Time Map Book: Take a Tour Juv.H515o of Six Enchanted Lands (Peter Pan, Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, Jack and then Beanstalk, Aladdin, Snow White) Jacobs, Joseph The buried moon; a tale told by Joseph Jacobs. Juv. 398.21 .J17b Jacobs, Joseph Indian fairy tales Juv.398.2 .J17i 1969 MacDonald, George, The golden key Juv. M135g Matsutani, Miyoko, The crane maiden. Juv. 98.21 .M434c My Storytime Collection of First Favorite tales Juv. 398.2.M995 2002 O’Malley, Kevin Once upon a cool motorcycle dude Juv. O543o (Two classmates try to tell a fairy tale to their class with some imaginative twists to some well-known fairy tale elements!) Oxenbury, Helen. Helen Oxenbury nursery story book. Juv. 398.21 .O98h San Jose, Christine Little Match Girl Juv. 398.21.A544j San Souci, Robert D. White Cat Juv.398.21.SS229w 1990 Singer, Marilyn Follow Follow: A book of Reverso poems Juv.811.54.S617f (Poems -

Inscape 2010 Inscape 2010

INSCAPE 2010 INSCAPE 2010 the literary magazine of Pasadena City College Pasadena, California Volume 65 (formerly Pipes of Pan, volumes 1-29) Inscape is the Pasadena City College student literary magazine. It appears once a year in the spring. PCC students serve as the magazine’s editors; editors market the magazine, review submissions, and design its layout . All PCC students—full or part-time—are invited to submit their creative writing and art to the magazine’s faculty advisor, Christopher McCabe. Submission guidelines and information regarding Inscape editorial positions are available in the English Division office in C245. Copyright 2010 by Inscape , English Division, Pasadena City College, Pasadena, California. Photography: Beth Andreoli Illustrations: N.S. David All rights revert to author and artist upon publication. 2 INSCAPE INSCAPE 3 Senior Editors Beth Andreoli N.S. David Ikia Fletcher W.R. Kloezeman Francisco Luna Associate Editors Mayli Apontti Mary Nurrenbern Assistant Editors Jane Coleman Johanna Deeb Diane Lam Andrea Miller Art Director Beth Andreoli Faculty Advisor Christopher McCabe 4 INSCAPE Inscape 2010 Award Winners Nonfiction FLAT TIRES by Jocelyn Lee-Tindage page 13 Poetry THE MANY FACES OF LA LLORONA by Vibiana Aparicio-Chamberlin page 21 MONKEY SEE, MONKEY DO by Tina R. Johnson page 41 Short Story HETEROCHROMIA IRIDIUM by Carlos Lemus page 54 INSCAPE 5 Contents Preface by N.S. David . 8 Towers of Ambition by Mathew Jackson . 11 Flat Tires by J.L. Tindage . 13 The Many Faces of La Llorona by Vibiana Aparicio-Chamberlin . 21 A Closed Distance by Luis Martinez . 22 Ode to the Drum by Ikia Fletcher . -

Commonlit | the Pied Piper of Hamelin

Name: Class: The Pied Piper of Hamelin By Robert Browning 1888 Robert Browning (1812-1889) was an English poet and playwright known for his dramatic verse. “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” published in 1888, is a poetic retelling of the German legend from the Middle Ages in which a man is hired to lure rats away from a town with his magic pipe. As you read, take notes on the Piper's actions and motivations. [1] Hamelin town's in Brunswick, By famous Hanover city; The River Weser, deep and wide, Washes its wall on the southern side; [5] A pleasanter spot you never spied; But, when begins my ditty, Almost five hundred years ago, To see townsfolk suffer so From vermin, was a pity. [10] Rats! They fought the dogs, and killed the cats, And bit the babies in the cradles, And ate the cheeses out of the vats, And licked the soup from the cook's own ladles, [15] Split open the kegs of salted sprats,1 "Pied Piper with Children" by Kate Greenaway is in the public Made nests inside men's Sunday hats, domain. And even spoiled the women's chats, By drowning their speaking With shrieking and squeaking [20] In fifty different sharps and flats. 1. a small fish of the herring family 1 At last the people in a body To the Town Hall came flocking: "'Tis clear," cried they, "our Mayor's a noddy;2 And as for our Corporation—shocking [25] To think we buy gowns lined with ermine3 For dolts4 that can't or won't determine What's best to rid us of our vermin! You hope, because you're old and obese, To find in the furry civic robe ease? [30] Rouse up, sirs! Give your brains a racking To find the remedy we're lacking, Or, sure as fate, we'll send you packing!" At this the Mayor and Corporation Quaked with a mighty consternation.5 [35] An hour they sat in council, At length the Mayor broke silence: "For a guilder6 I'd my ermine gown sell, I wish I were a mile hence! It's easy to bid one rack one's brain — [40] I'm sure my poor head aches again I've scratched it so, and all in vain. -

Fairy Tales & Legends: the Novels

Koertge, Ron. Lies, Knives and Girls in Red Dresses (Little Red Riding Hood) Levine, Gail Carson. Fairest (Snow White isn’t the fairest of them all) These are tales that are written in full Lo, Malinda. novel form, with intricately developed Ash (Cinderella) plots and characters. Sometimes the Marillier, Juliet. version is altered, such as taking place in a Wildwood Dancing (The Frog Prince different location or being told through and Twelve Dancing Princesses, set in the eyes of a different character. Transylvania) Anderson, Jodi Lynn. Martin, Rafe. Tiger Lily (Peter Pan) Birdwing (A continuation of Six Swans) Barron, T.A. Masson, Sophie. The Lost Years of Merlin series Serafin (Puss in Boots, only the cat is an Great Tree of Avalon series angel in disguise) Bunce, Elizabeth. McKinley, Robin. A Curse as Dark as Gold (Rumplestiltskin) Beauty (Beauty & the Beast) Coombs, Kate. Spindle’s End (Sleeping Beauty) The Runaway Princess Meyer, Marissa. (A new twist on old tales) Lunar Chronicles (Dystopian fairy tales) Crossley-Holland, Kevin. Meyer, Walter Dean. Arthur trilogy Amiri & Odette (Swan Lake set in the Projects) Delsol, Wendy. Stork trilogy (Snow Queen) Napoli, Donna Jo. Dokey, Cameron. Beast (Beauty & the Beast, set in Persia, Golden (Rapunzel) told from Beast’s point of view) Beauty Sleep (Sleeping Beauty) Breath (Pied Piper) Donoghue, Emma. Crazy Jack (Jack and the Beanstalk; Kissing the Witch (13 tales loosely Jack’s looking for his dad) connected to each other) The Magic Circle (Hansel & Gretel; the witch’s story) Durst, Sarah Beth. Ice (East of the Sun, West of the Moon) Pearce, Jackson. -

ANTI-AMERICANISMS in FRANCE Sophie Meunier

07-Meunier 5/26/05 3:39 PM Page 125 ANTI-AMERICANISMS IN FRANCE Sophie Meunier Princeton University France is undoubtedly the first response that comes to mind when asked which country in Europe is the most anti-American. Between taking the lead of the anti-globalization movement in the late 1990s and taking the lead of the anti-war in Iraq camp in 2003, France confirmed its image as the “oldest enemy” among America’s friends.1 Even before the days of De Gaulle and Chirac, it seems that France has always been at the forefront of anti-American animosity—whether through eighteenth-century theories about the degener- ation of species in the New World or through 1950s denunciations of the Coca-Colonization of the Old World.2 The American public certainly returns the favor, from pouring French wine onto the street to renaming fries and toast, and France has become the favorite bogeyman of conservative shows and provided material for countless late-night comedians’ jokes.3 Surprisingly, however, polling data reveals that France is not drastically more anti-American than other European countries—even less so on a variety of dimensions. The French do stand out in their criticism of US unilateral leadership in world affairs and in their willingness to build an independent Europe able to compete with the United States if needed.4 But their overall feelings towards the US were not dramatically different from those of other European countries in 2004.5 Neither was their assessment of the primary motives driving American foreign policy, and US Middle East policy in partic- ular.6 Furthermore, despite what seems like growing gaps in their societal val- ues (especially regarding religion), French and American public opinions agree on the big threats facing their societies, and they still share enough values to cooperate on international problems. -

Live to Re-Tell the Tale

Live to Re-tell the Tale.... Select a favourite fairy tale that you would like to re-tell. Then, choose one character from the story who will present the tale from his/her point of view. Consider the following questions as you think about your Re-told Tale: Will the story be different because of the character you have chosen? For example, if that character is a Big Bad Wolf or an Evil Witch, how might you change the story to reflect that character’s take on the story? Will there be added scenes in your tale based on the character you have chosen? For example, if you chose to tell the tale of Cinderella from the Fairy Godmother’s perspective, what might be different about your story (ie., before, during and after the ball?) How will the dialogue in the story be different as it comes from your character? Do you want to make your main character a more modernized, or nicer, or meaner version than in the original tale? What other information do you want to share about your character that might not have been part of the original story? You do not have to rewrite the entire tale, but can write a synopsis of it. (A synopsis is like a summary, that lets the reader or listener know what the whole story is about). Your synopsis can be in point form, in mini paragraphs, or in whatever form you like. You will present your story ORALLY to the group, so you can also think about how your presentation will be different than an entire written story. -

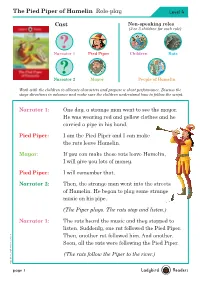

The Pied Piper of Hamelin Role-Play Level 4

The Pied Piper of Hamelin Role-play Level 4 Cast Non-speaking roles (2 or 3 children for each role) ? Narrator 1 Pied Piper Children Rats ? Narrator 2 Mayor People of Hamelin Work with the children to allocate characters and prepare a short performance. Discuss the stage directions in advance and make sure the children understand how to follow the script. Narrator 1: One day, a strange man went to see the mayor. He was wearing red and yellow clothes and he carried a pipe in his hand. Pied Piper: I am the Pied Piper and I can make the rats leave Hamelin. Mayor: If you can make these rats leave Hamelin, I will give you lots of money. Pied Piper: I will remember that. Narrator 2: Then, the strange man went into the streets of Hamelin. He began to play some strange music on his pipe. (The Piper plays. The rats stop and listen.) Narrator 1: The rats heard the music and they stopped to listen. Suddenly, one rat followed the Pied Piper. Then, another rat followed him. And another. Soon, all the rats were following the Pied Piper. (The rats follow the Piper to the river.) Copyright © LadybirdCopyright Books Ltd, 2018 page 1 The Pied Piper of Hamelin Role-play Level 4 Narrator 2: The Pied Piper walked toward the river. He was still playing the strange music on his pipe. The rats followed him and they all jumped into the river. And that was the end of the rats in Hamelin. (The Pied Piper returns to the mayor.) Narrator 1: The Pied Piper went back to see the mayor. -

Care Tactics Frightening Children Into Obedience with Tales of the Bogeyman Is No Longer Considered Sound Parenting, Writes Hazel Parry

(South China Morning Post 23 Oct, 2004) Care Tactics Frightening children into obedience with tales of the bogeyman is no longer considered sound parenting, writes Hazel Parry THEY WERE FIVE words to strike terror into the heart of any young child -words every calculating parent knew would bring an instant end to juvenile obstinacy and guarantee immediate, trembling obedience: "The bogeyman will get you." He'd get you if you stayed up later than you should. He'd get you if you went somewhere you shouldn't. He'd get you if you didn't do your homework. And he'd get you if you weren't nice to your baby brother or sister. Shadowy and amorphous, he'd grab your feet when you stepped out of bed at night and chase you, unseen, down dark lanes - and the only way to spot him was to look quickly through a knothole in a wooden partition, when you might see the dull gleam of his eye. The bogeyman has spread fear through generations of children around the world for four centuries, his sinister form hiding in the dark corners of millions of bedrooms. Today, his powers are fading. In the space of a generation, the bogeyman has been transformed from a child's worst nightmare into a figure of speech and, increasingly, a remote and comical- sounding anachronism. The bogeyman is being killed by kindness and the relatively new idea that it's bad to frighten children. "Today, parents view scaring their children as inappropriate," says anthropologist Joseph Bosco of the Chinese University. -

La Llorona, Picante Pero Sabroso: the Mexican Horror Legend As a Story of Survival and a Reclamation of the Monster

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School Spring 2021 La Llorona, Picante Pero Sabroso: The Mexican Horror Legend as a Story of Survival and a Reclamation of the Monster Camille Maria Acosta Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Chicana/o Studies Commons, Folklore Commons, Latina/o Studies Commons, Oral History Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Acosta, Camille Maria, "La Llorona, Picante Pero Sabroso: The Mexican Horror Legend as a Story of Survival and a Reclamation of the Monster" (2021). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 3501. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/3501 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LA LLORONA, PICANTE PERO SABROSO: THE MEXICAN HORROR LEGEND AS A STORY OF SURVIVAL AND A RECLAMATION OF THE MONSTER A Thesis Presented to The Faculty in the Department of Folk Studies and Anthropology Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Camille Maria Acosta May 2021 LA LLORONA; PICANTE PERO SABROSO: THE MEXICAN HORROR LEGEND AS A STORY OF SURVIVAL AND A RECLAMATION OF THE MONSTER Date Recommended_____________________4/2/21 Katherine Horigan Katherine_____________________________________ Horigan (Apr 6, 2021 16:27 CDT) Dr. Kate Horigan, Director of Thesis Ann Ferrell Ann_____________________________________ Ferrell (Apr 7, 2021 08:59 CDT) Dr. -

Programm Kultur Nacht 22.06

Anzeige 13. BRAUNSCHWEIGER KULTUR NACHT SAMSTAG 22.06. Veranstalter Förderer PROGRAMM Medienpartner 300 Veranstaltungen 100 Orte Anzeige • Seite 2 Anzeige • Seite 3 18 UHR FALOW 5 ALTSTADT- 6 ATELIER / Rock / Pop Pin-Verkauf während der Kulturnacht Oldtimer-Cruise ERÖFFNUNG AUF DEM 19.0 5 – 19. 5 5 U hr RATHAUS STUDIO HOPPE 13. BRAUNSCHWEIGER • an den Info-Points (siehe unten) Der Büssing-Bus macht den Wechsel Dornse, Altstadtmarkt 7 Schimmel-Hof, Eingang B7, • an zahlreichen Veranstaltungs- zwischen den vielen Orten leichter! SCHLOSSPLATZ Pop- und Rocksongs der 60er bis Hamburger Straße 273 B Mehr Informationen zu den Pro- heute, interpretiert von zwei Mu - orten (siehe letzte Seite) Folgende Haltepunkte werden accordion breeze grammpunkten der Eröffnung fin - sikern mit viel Herzblut. • bei unseren Bauchladen- angefahren: Akkordeonmusik Ausstellung ›Sprechzeit‹ det ihr unter ›Schlossplatz‹ 92 Das ist FALOW! verkäufern*innen • Fr.-Wilhelm-Platz 18 – 18.30 Uhr • Foyer 18.30 Uhr, 20 Uhr & 21 Uhr auf Seite 15. (Haltestelle der Straßenbahn) KULTUR Vier Akkordeons aus der Akkor- Führungen durch das große Kulturnacht-Hotline Falter Band • Haltestelle Schloss deonschule Heike Lachetta spielen Ate lier mit Erläuterungen zum 0531 470-4844 nur während der Funk, Soul, Rock (Linienbus haltestelle der 420) Matroschka-Folk. Herstellungsprozess des Bronze- Kulturnacht von 12 – 24 Uhr 2 0 .1 5 – 2 1 U hr • halle267 (Hamburger Straße 267) 1 ALBA KUNDEN- Akkordeonmusik voller Sehnsucht gusses sowie Besichtigung der Die Nutzung des Büssing-Busses Musik von dieser Welt – eine kul- NACHT Info-Points während der Kulturnacht und Temperament. aktuellen Ausstellung mit Hilu ist kostenlos, aber nur mit Kultur- ZENTRUM turelle Rundreise durch populäre Kahmann-Frey und Güde Renken • 16 – 23 Uhr auf dem Schlossplatz 92 nacht-Pin möglich.