First Few Days Look Disastrous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

Canterbury Christ Church University's Repository of Research Outputs Http

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Canterbury Research and Theses Environment Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. Revell, S. (2018) The 1953 coup in Iran: U.S. and British foreign policy in Iran, 1951-1953 and the covert operation to overthrow the elected government of Mohammad Mosaddeq. M.A. thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University. Contact: [email protected] The 1953 Coup in Iran: U.S. and British Foreign Policy in Iran, 1951-1953 and the Covert Operation to Overthrow the Elected Government of Mohammad Mosaddeq by Stephen Revell Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the degree of Masters by Research 2018 Abstract The 1953 coup in Iran that overthrew the elected government of Mohammad Mosaddeq had a profound effect on Iranian history and U.S.-Iranian relations. The covert operation by the U.S. and British intelligence agencies abruptly ended a period of Iranian democracy and with it, efforts to nationalise the Iranian oil industry. -

Download This Issue As A

Columbia College Fall 2013 TODAY MAKING A DIFFERENCE Sheena Wright ’90, ’94L Breaks Ground as First Woman CEO of United Way of New York City NETWORK WITH COLUMBIA ALUMNI BILL CAMPBELL, CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS, INTUIT MEMBER OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS, APPLE MEMBER OF THE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY CLUB OF NEW YORK The perfect midtown location to network, dine with a client, hold events or business meetings, house guests in town for the weekend, and much more. To become a member, visit columbiaclub.org or call 212-719-0380. in residence at The Princeton Club of New York 15 WEST 43 STREET NEW YORK, NY 10036 Columbia Ad_famous alumni.indd 6 11/8/12 12:48 PM Contents FEATURES 14 Trail Blazer 20 Loyal to His Core Sheena Wright ’90, ’94L is breaking As a Columbia teacher, scholar and ground as the first female CEO of alumnus, Wm. Theodore de Bary ’41, ’53 United Way of New York City. GSAS has long exemplified the highest BY YELENA SHUSTER ’09 standards of character and service. BY JAMIE KATZ ’72, ’80 BUSINEss 26 New Orleans’ Music Man 34 Passport to India After 25 years in NOLA, Scott Aiges ’86 Students intern in Mumbai, among is dedicated to preserving and other global sites, via Columbia promoting its musical traditions. Experience Overseas. BY ALEXIS TONTI ’11 ARTS BY SHIRA BOss ’93, ’97J, ’98 SIPA Front cover: After participating in a United Way of New York City read-aloud program at the Mott Haven Public Library in the Bronx, Sheena Wright ’90, ’94L takes time out to visit a community garden in the neighborhood. -

Preface Introduction

Notes Preface 1. William Roger Louis, ‘Britain and the Overthrow of the Mosaddeq Govern- ment’, in Mark Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne (eds), Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2004), p. 126. 2. Kermit was the grandson of President Theodor Roosevelt; his account of the events was narrated in his book, Countercoup: The Struggle for the Control of Iran (New York: McGraw- Hill, 1979). 3. This CIA internal report, entitled ‘Clandestine Service History; Overthrow of Pre- mier Mossadeq [sic] of Iran, November 1952–August 1953’ (hereinafter referred to as Overthrow). The author is Donald Wilber who, as Iran point-man at CIA headquarters in Washington, had a hand in the drafting of the coup plot against Mosaddeq codenamed TPAJAX. He was not, however, in Iran at the time of the events in August 1953. Introduction 1. On 13 March 1983, commemorating the twenty-first anniversary of the death of Ayatollah Kashani, Iran’s parliamentary Speaker, later President, Ali-Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani made the following statement: ‘We honour the memory of the exalted Ayatollah Kashani and request the Iranian nation to participate in the commemoration ceremonies that will be held tomor- row and in the following days; on the same occasion we should express indignation over the injustice done to him and to the Islamic movement by the nationalists [i.e., the Mosaddeq supporters] and the blow inflicted by them on the Islamic movement in one episode in Iran’s history. On this historical day, we express our sorrow to his honourable family and to the Iranian nation and celebrate the life of this great man.’ See, Hashemi- Rafsanjani and Sara Lahooti, Omid va Delvapasi¯ , karnameh¯ va khater¯ at’e¯ Hashemi Rafsanjani, sal’e¯ 1364 (Hope and Preoccupation, the Balance-Sheet and Memoirs of Hashemi-Rafsanjani, year 1364/1985), (Tehran: Daftar’e Nashr’e Ma’aref’e¯ Eslami publishers, 2008), p. -

Egypt and the Soviet Union, 1953-1970

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1986 Egypt and the Soviet Union, 1953-1970 John W. Copp Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the African Studies Commons, History Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Copp, John W., "Egypt and the Soviet Union, 1953-1970" (1986). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3797. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5681 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE thesis of John w. Copp for the Master of Arts in History presented April 7, 1986. Title: Egypt and the Soviet Union, 1953-1970 APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE~IS COMMITTEE -------- --------- The purpose of this study is to describe and analyze in detail the many aspects of the Soviet-Egyptian friendship as it developed from 1953 to 1970. The relationship between the two is extremely important because it provides insight into the roles of both Egypt aand the Soviet Union in both the history of the Middle East and in world politics. The period from 1953 to 1970 is key in understanding the relationship between the two states because it is the period of the genesis of the relationship and a period in which both nations went through marked changes in both internal policy and their external relations. -

A Cold War Narrative: the Covert Coup of Mohammad Mossadegh, Role of the U.S

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2013 A Cold War Narrative: The Covert Coup of Mohammad Mossadegh, Role of the U.S. Press and Its Haunting Legacies Carolyn T. Lee Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Cultural History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Carolyn T., "A Cold War Narrative: The Covert Coup of Mohammad Mossadegh, Role of the U.S. Press and Its Haunting Legacies". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2013. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/300 A COLD WAR NARRATIVE: THE COVERT COUP OF MOHAMMAD MOSSADEGH, ROLE OF THE U.S. PRESS AND ITS HAUNTING LEGACIES A SENIOR THESIS BY CAROLYN T. LEE INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ART HISTORY A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MAJOR IN INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, TRINITY COLLEGE THESIS ADVISOR: ZAYDE GORDON ANTRIM, PH.D. ABSTRACT In 1953 the British and United States overthrew the democratically elected Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in what was the first covert coup d’état of the Cold War. Headlines and stories perfectly echoed the CIA and administration’s cover story – a successful people’s revolution against a prime minister dangerously sympathetic to communism. This storyline is drastically dissimilar to the realities of the clandestine operation. American mainstream media wrongly represented the proceedings through Iran strictly Cold War terms rather than placing it in it rightful context as a product of the Anglo-Iranian oil nationalization crisis. -

Britannia's Suez Fiasco in Consideration of Anglo-American Diplomacy

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship January 2016 The Stress of Her Disregard: Britannia’s Suez Fiasco in Consideration of Anglo-American Diplomacy Matthew Gerth Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Diplomatic History Commons Recommended Citation Gerth, Matthew, "The Stress of Her Disregard: Britannia’s Suez Fiasco in Consideration of Anglo-American Diplomacy" (2016). Online Theses and Dissertations. 367. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/367 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Stress of Her Disregard: Britannia’s Suez Fiasco in Consideration of Anglo- American Diplomacy By Matthew C. Gerth Bachelor of Arts Eastern Kentucky University Richmond, Kentucky 2013 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2016 Copyright © Matthew Gerth, 2016 All rights reserved ii To Dr. Iva Marie Thompson For inspiration comes from the most unlikely of places iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks must go to many who aided in the completion of this thesis. Anything worthy of praise within its pages is to their credit; likewise, all mistakes or missteps rest directly on me. First, I cannot overstate my appreciation to the committee chair, Dr. Ronald Huch. For the past two years, he has been my professional and personal mentor. -

OPC Urges Obama to End Excessive Secrecy

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • June 2013 OPC Urges Obama to End Excessive Secrecy by Susan Kille, Larry Martz and Aimee Vitrak The OPC’s Freedom of the Press Committee has written hundreds of letters to foreign governments pro- testing abuses of the press. It is tes- timony to the success of democracy in America that relatively few such letters have been needed at home. In the past ten years, however, the Committee has written 18 letters complaining of press freedom abus- es by the Bush and Obama admin- istrations. A year ago, the Commit- President Obama announced a review of press freedom guidelines tee organized a panel in Washington during a major speech on defense and security on May 23. D.C., co-sponsored with the Na- He set a deadline of 12 July for a response. tional Press Club, calling attention to President Obama’s prosecution of its reach with journalists had stopped six government whistle-blowers un- there, but on the heels of the AP re- OPC Letter to Obama der the Espionage Act – more than port arrived news of a Fox News re- all such cases put together since the porter. James Rosen broke the news May 28, 2013 Act was passed in 1917. But the May that North Korea was planning mis- Dear Mr. President: 13 disclosure that the Department of sile launches in fierce defiance of the Justice has subpoenaed two months U.N. Security Council’s 2009 con- The Overseas Press Club of of records from 2012 of more than demnation of Pyongyang’s nuclear America thanks you for your ac- 20 telephone lines used by AP re- program. -

The Suez Crisis of 1956 and the Anglo-American

DIVIDED WE STAND: THE SUEZ CRISIS OF 1956 AND THE ANGLO-AMERICAN 'ALLIANCE' W. Scott Lucas Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in accordance with the requirements of the London School Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U048352 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U048352 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Library British Library of Political and Economic Saence \Vb<o SS3 ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is two-fold. Firstly, using recently-released American, British, and Israeli documents, private papers, and oral evidence in addition to published work, it re-evaluates the causes and development of the Suez Crisis of 1956. Secondly, it examines the operation of the Anglo-American 'alliance' in the Middle East, if one existed, in the 1950s by considering not only the policymaking structures and personalities involved in 'alliance' but also external factors, notably the actions of other countries, affecting relations between the American and British Governments. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the staffs of the British Public Record Office, the U.S. -

New York Times Covers and Aids 1983 Cia Coup in Iran

Vol.4 No.4 SPECIAL ISSUE SEPT./OCT. 1980 50c New Revelations: New C.I.A. Bill: New York Times Death to the Covers and Aids First Amendment 1953 CJ.A. Coup in Iran CounterSp¥ magazine is issuing the following special report be Iranians of different socio-eco cause it poignantly illustrates nomic strata and backgrounds vary the devastating damage resulting in their grievances against the from collaboration between the · U.S. government but agree o� the press· and the CIA, and because it event of greatest disdain: the CIA addresses the present threat to masterminded coup of August 1953. freedom of the press and the U.S. The coup replaced the constitution Constitution posed by HR5615 and al government of Mohammed Mossadegh S2216 pending in Congress. These with that of a pro-Nazi named two bills make it a crime to name Zahedi and marked the onset of 25 undercover CIA and FBI officers, years of Shah-led dictatorial rule. agents, and informers or to pub An event of such historic impor lish information that could lead tance was bo und to generate contro to the disclosure of a CIA or FBI versies and consequences even three name,· even if all the information decades later. Indeed, Iranians' is obtained from public sources. fears that the October 1979 admis This report is about Kennett sion of the Shah to the U.S. for Love whose personal role in the "medical reasons" signalled another CIA's 1953 coup in Iran was de CIA-masterminded coup served as a scribed as foll0ws by.Paul Nitze, catalyst for the embassy seizure. -

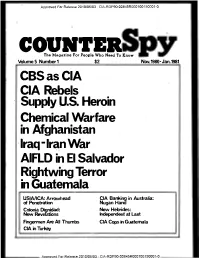

Counterspy: Cbs As

Approved For Release 2010/06/03: CIA-RDP90-00845R000100150001-0 The Magazine For People Who Need To Know VolumeCOUNTE5 Number 1 $2 R Nov.1980-Jan.1981 CBSasCIA CIA Rebels · SupplyU.S. Heroin Chemical Warfare in Afghanistan , Iraq· lr(ilnWar AIFLD in El Salvador · Rightwing Terror in Guatemala USIA/ICA: Arrowhead CIA Bari(ing in Australia: of Penetration Nugan Hand Colonia Dignidad: New Hebrides: New Revelations Independent at Last Fingermen AreAll Thumbs CIA Copsin Guatemala CIA inTurkey Approved For Release 2010/06/03: CIA-RDP90-00845R000100150001-0 Approved For Release 2010/06/03: CIA-RDP90-00845R000100150001-0 Editorial / Due to public opposition and despite :Lh- In response to the press conference, the ; tense illegal lobbying by the CIA, the New York Times issued a stateme'nt of con "I�telligence Identiti�s Protection Act'" siderable import: failed to reach a floor'vote in Congress "N_? editor or executive of this paper before it recessed. ,HR5615 and S2216�would has any knowledge of what Love was sup make it a crime to disclose information posed to have .done 271 years ago. What leading to the identification of CIA and- every editor and executive of this pa ' FBI officers, agents and informers, even per does know, however, is that The New it the information whi�h led to the iden York Times has an absolute rule against tification was already public. any reporter working for any government _ Some Senators and Representatives are agency.. This paper has repeatedly urged, opposed to the present bills because tbey .President carter to reverse the CIA's a.re unconstitutional. -

1 Mark J. Gasiorowski, “The 1953 Coup D'état Against Mosaddeq,”

Mark J. Gasiorowski, “The 1953 Coup d’État Against Mosaddeq,” in Mark J. Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne, eds., Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2004), pp. 227-260, 329-339. In November 1952, Christopher Montague Woodhouse of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and Sam Falle of Britain’s Foreign Office met with officials of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in Washington. Their ostensible purpose was to discuss covert operations the two countries were undertaking in Iran to prepare for a possible war with the Soviet Union. After these discussions, they proposed that the United States and Britain jointly carry out a coup d’état against Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq. The British had been trying to overthrow Mosaddeq since he was named prime minister in April 1951, after leading a movement to nationalize Iran’s British-controlled oil industry. Their latest effort, undertaken in collaboration with retired General Fazlollah Zahedi, had collapsed in October 1952, resulting in the arrest of several of Zahedi’s collaborators and leading Mosaddeq to break diplomatic relations with Britain. Having failed repeatedly to overthrow Mosaddeq, and no longer having an embassy to work from in Iran, the British hoped the Americans now would take up the task.1 The CIA officials who participated in this initial meeting were surprised by the British proposal and said only that they would study it. Woodhouse and Falle then met with Assistant Secretary of State Henry Byroade and other State Department officials, who were unenthusiastic about the proposal but also agreed to study it.