UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

Kings Valley – from Amenhotep III to Horemheb by Antonio Crasto

Kings Valley – from Amenhotep III to Horemheb by Antonio Crasto The royal necropolis The western area on the left bank of the Nile opposite the ancient city of Waset / Theban was dedicated to the necropolis and the temples of the millions of years, in which it was celebrated the cult of the kings after their death. During the eighteenth dynasty, a different religious outlook led the pharaoh woman Hatshepsut to open a new royal necropolis, the Kings Valley, at the foot of the sacred mountain, whose top Dehenet "The top" assumes, view from the Valley, the pyramidal form. The mountain was sacred to the goddess with the head of cobra Mertseger, protector of the necropolis and syncretic form of the mother goddess Hathor. Hatshepsut wanted to be buried in the "belly" of the mother goddess, the goddess who, as a celestial cow, had protected her at birth and nursed symbolically. The "Top" which overlooks the Kings Valley The necropolis was used during the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth dynasty ensuring the burial of about thirty kings. Made except two kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty, Amenhotep III (1433 - 1394 BC 1) and Ay (1373 - 1368 BC 1), whose graves were dug, by choice of the sovereign or after their death, in the secondary Kings Valley, the West Valley. WV 22 e 23 Most Egyptologists consider it natural, but others believe that the West Valley has been a last resort, not having the two pharaohs been allowed for a burial in the main valley or not having the priesthood of Amun, keeper of the Valley, granted the permission for burial in the tomb they had dug in the main valley. -

The Religious Reforms of Akhenaten and the Cult of the Aten

The Pharaoh’s Sun-Disc : The Religious Reforms of Akhenaten and the Cult of the Aten The 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Akhenaten, known to many as the “Heretic King,” made significant changes to the religious institutions of Ancient Egypt during his reign in the 14th century BCE. The traditional view long maintained that these reforms, focused on the promotion of a single solar god known as the Aten, constituted an early form of monotheism foreshadowing the rise of Western Biblical tradition. However, this simplification ignores the earlier henotheistic tendency of Egyptian polytheism and the role of Atenism in strengthening the Pharaoh’s authority in the face of the powerful Amun-Ra priesthood, as well as distinctions between the monotheism of Moses and Akhenaten’s cult. Instead, the religion of Akhenaten, which developed from earlier ideas surrounding the solar deity motif, can be seen as an instance of monotheistic practice in form but not in function, characterized by a lack of conviction outside the new capital of Akhetaten as well as an ultimate goal of establishing not one god but one ruling power in Egypt: the Pharaoh. This will become clear through an analysis of the background to Akhenaten’s reign, the nature of his reforms and possible motivations, and the reality of Atenism vis-à-vis later Biblical monotheism. The “revolution” of Akhenaten, born Amunhotep IV,1 evidently had significant implications both during and after his reign. The radical nature of his reforms is clearly visible in the later elimination of his name and those of his immediate successors from the official list of rulers.2 However, it is possible to see the roots of these changes, and perhaps of the Pharaoh’s motivations, in earlier developments in the importance and form 1 Greek Amunhopis IV. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

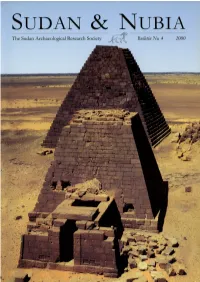

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Long Cruise from Luxor to Cairo 9 Nights ‐ 10 Days Cruise

Long Cruise From Luxor To Cairo 9 Nights ‐ 10 Days Cruise Day 1 Embarkation on cruise in Luxor and Overnight. Music in the bar. Overnight in Luxor. Day 2 Visit the West Bank ‐‐ Valley of the Kings & Temple of Queen Hatshepsut (El‐ 07:00 Deir El‐Bahari). 14:00 Visit East bank (Karnak & Luxor Temples). Belly Dancer. Overnight in Luxor. Day 3 04:00 Early Sail to Qena. 08:30 Visit Abydos Temple 14:30 Visit Dendara Temple Back to Ship in Qena. Contest Party. Overnight in Qena. Day 4 05:30 Sail to Sohag. Via Naga Hammadi Bridge and Abu Homar’s Lock. Treasure Hunt. Arrive to Sohag & Overnight. Day 5 Full Day cruising. Cross Sohag Bridge and Sail to Minya via Asyuit’s Lock. Black & White Party. Arrive to Minya & Overnight. Day 6 07:00 Visit Tel El Amarna. Visit to northern tombs Tomb of Ahmose (EA3), Tomb of Meryre (EA4), Tomb of Pentu (EA5), Tomb of Panehesy (EA6), and Royal Tomb of Akhenaten (EA26). The Great Palace of King Akhenaten, The Small and great temples of Aten (Approx. 3 hours visit). 12:30 Visit Tuna El Gebel & Ashmunein. Lunch box will be served within the Visits. Folkloric Show. Overnight in Minya. Day 7 Visit Beni Hassan (4 tombs) Half an hour drive from Minya dock (25 KM.) to 08:00 visit Tomb of Baqet III (BH15) Tomb of Khety (BH17), Tomb of Amenemhet (BH2), Tomb of Khnumhotep II (BH3) (Approx. 2 hour visit) . 10:30 Sail to Beni Suif. Galabya Party. 18:00 Arrive to Beni Suif & Overnight. -

The President's Papyrus

Volume 18, Number 1, June 2012 The President’s Papyrus Published twice per year since 1993 Greetings fellow Amarnaphiles! I hope that this finds you well and Copyright 2012, The Amarna prospering. If you are following the news, you know that the Research Foundation political future of Egypt remains uncertain. However, in the last Sun newsletter, I announced that we were in the process of creating a whole new TARF website. Well, when you receive this issue of the Sun the new website should be fully operational and available for all to see and explore. We here at the Foundation are very Table of Contents excited with this new development and hope that you will be too. The website graphics are done in the classic Amarna style. Please, Article -- Author Page let us know what you think about it and how you think it can be What Borchardt Left Behind -- improved. It is our sincere hope that the new website will be the Kristin Thompson 2 catalyst for renewed interest in the unique period of Egyptian history, producing new TARF members as well. Please take a few Making a Start minutes to go to our new website and take a look around. at the Great Aten Temple -- www.theamarnaresearchfoundation.org Barry Kemp 7 Our annual meeting this year on September 16 will include a lecture by Barry Kemp on his work at Amarna. We hope you will be able to attend this event. As always, nominations for candidates for the Board of Trustees will be accepted prior to our meeting. -

Egyptian Religion a Handbook

A HANDBOOK OF EGYPTIAN RELIGION A HANDBOOK OF EGYPTIAN RELIGION BY ADOLF ERMAN WITH 130 ILLUSTRATIONS Published in tile original German edition as r handbook, by the Ge:r*rm/?'~?~~ltunf of the Berlin Imperial Morcums TRANSLATED BY A. S. GRIFFITH LONDON ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO. LTD. '907 Itic~mnoCLAY B 80~8,L~~II'ED BRIIO 6Tllll&I "ILL, E.C., AY" DUN,I*Y, RUFIOLP. ; ,, . ,ill . I., . 1 / / ., l I. - ' PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION THEvolume here translated appeared originally in 1904 as one of the excellent series of handbooks which, in addition to descriptive catalogues, are ~rovidedby the Berlin Museums for the guida,nce of visitors to their great collections. The haud- book of the Egyptian Religion seemed cspecially worthy of a wide circulation. It is a survey by the founder of the modern school of Egyptology in Germany, of perhaps tile most interest- ing of all the departments of this subject. The Egyptian religion appeals to some because of its endless variety of form, and the many phases of superstition and belief that it represents ; to others because of its early recognition of a high moral principle, its elaborate conceptions of a life aftcr death, and its connection with the development of Christianity; to others again no doubt because it explains pretty things dear to the collector of antiquities, and familiar objects in museums. Professor Erman is the first to present the Egyptian religion in historical perspective; and it is surely a merit in his worlc that out of his profound knowledge of the Egyptian texts, he permits them to tell their own tale almost in their own words, either by extracts or by summaries. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

Relations in the Humanities Between Germany and Egypt

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg HANS ROBERT ROEMER Relations in the humanities between Germany and Egypt On the occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907 – 1982) Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Ägypten, Dauer und Wandel : Symposium anlässlich d. 75jährigen Bestehens d. Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Kairo. Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern, 1985, S.1 - 6 Relations in the Humanities between Germany and Egypt On the Occasion of the Seventy Fifth Anniversary of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (1907-1982) by HANS ROBERT ROEMER I The nucleus of the Institute whose jubilee we are celebrating today was established in Cairo in 1907 as »The Imperial German Institute for Egyptian Archaeology«. This was the result of a proposal presented by the Berlin Egyptologist Adolf Erman on behalf of the commission for the Egyptian Dictionary, formed by the German Academies of Sciences. This establishment had its antecedents in the 19th century, whose achievements were not only incomparable developments in the natural sciences, but also an unprecedented rise in the Humanities, a field in which German Egyptologists had contributed a substantial share. It is hence no exaggeration to consider the Institute the crowning and the climax of the excavation and research work accomplished earlier in this country. As a background, the German-Egyptian relations in the field of Humanities had already had a flourishing tradition. They had been inaugurated by Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-84) with a unique scientific work, completed in 1859, namely the publication of his huge twelve-volume book »Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Nubien« (»Monuments from Egypt and Nubia«), devoted to the results of a four-year expedition that he had undertaken. -

Egyptian Magic Publishers’ Note

S.V. JBooftg on Bagpt anft Cbalfta?a VOL. II. EGYPTIAN MAGIC PUBLISHERS’ NOTE. In the year 1894 Dr. Wallis Budge prepared for Messrs. Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibner & Co. an elementary work on the Egyptian language, entitled “First Steps in Egyptian,” and two years later the companion volume, “ An Egyptian Reading Book,” with transliterations of all the texts printed in it, and a full vocabulary. I he success of these works proved that they had helped to satisfy a want long felt by students of the Egyptian language, and as a similar want existed among students of the languages written in the cuneiform character, Mr. L. W. King, of the British Museum, prepared, on the same lines as the two books mentioned above, an elementary work on the Assyrian and Babylonian languages (“First Steps in Assyrian”), which appeared in 1898. These works, however, dealt mainly with the philological branch of Egyptology and Assyriology, and it was impossible in the space allowed to explain much that needed explanation in the other branches of these subjects—that is to say, matters relating to the archaeology, history, religion, etc., of the Egyptians, Assyrians, and Babylonians. In answer to the numerous requests which have been made, a series of short, popular handbooks on the most important branches of Egyptology and Assyriology have been prepared, and it is hoped that these will serve as introductions to the larger works on these subjects. The present is the second volume of the series, and the succeeding volumes will be published at short intervals, and at moderate prices. -

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1

The Writing of the Birds. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Before and After the Founding of Alexandria1 Stephen Quirke, UCL Institute of Archaeology Abstract As Okasha El Daly has highlighted, qalam al-Tuyur “script of the birds” is one of the Arabic names used by the writers of the Ayyubid period and earlier to describe ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. The name may reflect the regular choice of Nile birds as signs for several consonants in the Ancient Egyptian language, such as the owl for “m”. However, the term also finds an ancestor in a rarer practice of hieroglyph users centuries earlier. From the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods and before, cursive manuscripts have preserved a list of sounds in the ancient Egyptian language, in the sequence used for the alphabet in South Arabian scripts known in Arabia before Arabic. The first “letter” in the hieroglyphic version is the ibis, the bird of Thoth, that is, of knowledge, wisdom and writing. In this paper I consider the research of recent decades into the Arabian connections to this “bird alphabet”. 1. Egyptological sources beyond traditional Egyptology Whether in our first year at school, or in our last year of university teaching, as life-long learners we engage with both empirical details, and frameworks of thought. In the history of ideas, we might borrow the names “philology” for the attentive study of the details, and “philosophy” for traditions of theoretical thinking.2As the classical Arabic tradition demonstrates in the wide scope of its enquiry and of its output, the quest for knowledge must combine both directions of research in order to move forward. -

A New Approach to the Interpretation As to the Function of the Elevated Beds Discovered at Deir El-Medina

A NEW APPROACH OF IDENTIFING THE FUNCTION OF THE ELEVATED BEDS AT DEIR EL-MEDINA by MICHELLE LESLEY BROOKER A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (B) Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity The University of Birmingham 11/06/09 June 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This research consists of a different approach to the investigation of the elevated beds at Deir el-Medina. It identifies the underlining factors considered during their construction, where they were positioned, how they were orientated and what the surviving iconographies suggested about their original usage. It concludes with identifying the front rooms at Deir el-Medina as gardens. The frontal room is where the elevated beds were positioned and therefore link to the gardens symbolic meaning of resurrection and the afterlife. The elevated beds were orientated to symbolize the deceases’ connection with Re and Osiris. It also signifies a change after the Amarna period with an influx in Osiris worship. The iconographies surviving upon the elevated beds convey the deceased being reborn within the field of reeds signifying that the elevated beds were possibly used for altar purposes.