Sikkim University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Extremism and Sectarianism in Pakistan: JRSP, Vol

Religious Extremism and Sectarianism in Pakistan: JRSP, Vol. 58, No 2 (April-June 2021) Samina Yasmeen1 Fozia Umar2 Religious Extremism and Sectarianism in Pakistan: An Appraisal Abstract Pakistan, which was created on the basis of religion have had to face sectarian violence and religious intolerance from the very beginning. This article offers an in-depth analysis of sectarianism and religious intolerance and their direct role in the current chaotic state of Pakistan. This article revolves around the two main research questions including the role of religion in the state of Pakistan as well as the evidences depicting sectarian violence in Pakistan. The main objective is to analyze the future situation of the rampant sectarian condition in the society and to study the role of Pakistan’s government so far. Qualitative methodology using primary as well as secondary sources are used to gather the data. Post-dictatorship era, after 2007, is being analyzed in this article, keeping in view the history of sectarian violence, future and stability of the state. Last comments lead to the recommendations and ways to tackle the sectarian divide and religious extremism. The researchers conclude that religion is core at the Pakistan’s nationalism however, religious extremism weakens national and social cohesion and also divides loyalties. There is a need for strict blasphemy laws, banning hate speeches which incites the violence and most importantly, eradicating poverty and unemployment, so no foreign elements can bribe anyone for sectarian terror within the state. Introduction Pakistan was a country that was created on the basis of religion, its main goal was to provide a homeland for Muslims where they will live in freedom and harmony and it was established that it will be governed according to the principles set by Islam. -

Current Affairs August 2016

VISION IAS www.visionias.in CURRENT AFFAIRS AUGUST 2016 Copyright © by Vision IAS All rights are reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of Vision IAS. 1 www.visionias.in ©Vision IAS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. POLITY ___________________________________________________________________________ 7 1.1. Urban Governance: Directly Elected Mayors ________________________________________________ 7 1.2. Competitive Federalism _________________________________________________________________ 8 1.3. Issues Related to Regulatory Bodies in India ________________________________________________ 9 1.4. Demand for Special Category Status ______________________________________________________ 11 1.5. Pendency of Cases in Courts in India ______________________________________________________ 12 1.6. ECI Seeks More Powers ________________________________________________________________ 13 1.7. Monsoon Session of Parliament-Assessment _______________________________________________ 14 1.8. The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016 ___________________________________________________ 14 1.9. Institutes of Technology (Amendment) Bill, 2016 ___________________________________________ 15 1.10. The Lokpal and Lokayuktas (Amendment) Bill, 2016 ________________________________________ 16 1.11. Saurashtra Narmada Avtaran Irrigation (SAUNI) Project _____________________________________ 16 1.12. Reservation -

Punjab Judicial Academy Law Journal

Punjab Judicial Academy Law Journal June, 2020 Copyright © 2020 by PUNJAB JUDICIAL ACADEMY 2 Punjab Judicial Academy Law Journal (PJALJ) Published by: The Punjab Judicial Academy 15-Fane Road, Lahore Tel: +92-42-99214055-58 Email: [email protected] www.pja.gov.pk 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Editorial Team of this first volume of the Punjab Judicial Academy Law Journal wish to thank Professor Dr. Dil Muhammad Malik, former Principal and Dean Faculty of Law, Punjab University Law College, Lahore, Dr. Khursheed Iqbal, AD&SJ, Mardan, Dr. Muhammad Ahmad Munir Mughal, In-charge Publications/Deputy Editor, Islamic Studies, IIU, Islamabad and Dr. Shahbaz Ahmad Cheema, Assistant Professor, Punjab University Law College, Lahore for their assistance in the publication of the this Journal. 4 EDITORIAL TEAM Patron-in-Chief: Honourable Mr. Justice Muhammad Qasim Khan, Chief Justice, Lahore High Court, Lahore / Chairperson, Board of Management, Punjab Judicial Academy Patrons: Honourable Mr. Justice Syed Shahbaz Ali Rizvi, Member, Board of Management, Punjab Judicial Academy Honourable Mr. Justice Shehram Sarwar Ch., Member, Board of Management, Punjab Judicial Academy. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Habibullah Amir, Director General, Punjab Judicial Academy Editor: Mr. Muhammad Azam, Director (Research & Publications), Punjab Judicial Academy Member Editorial Board: Syed Nasir Ali Shah 5 C O N T E N T S (1) A REVIEW OF THE BOOK “FAMILY LAWS IN PAKISTAN, BY MUHAMMAD ZUBAIR ABBASI AND SHAHBAZ AHMAD CHEEMA, KARACHI: OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS,2018” 7 Justice (R) Dr. Munir Ahmad Mughal (2) CLASSIFICATION OF PRISONERS INTO ORDINARY, BETTER, AND POLITICAL CLASS IN THE PRISONS ON ACCOUNT OF SOCIAL STATUS: A DENIAL OF LAW OF EQUALITY 17 Dr. -

Religious Movements, Militancy, and Conflict in South Asia Cases from India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan

a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religious Movements, Militancy, and Conflict in South Asia cases from india, pakistan, and afghanistan 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Authors E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Joy Aoun Liora Danan Sadika Hameed Robert D. Lamb Kathryn Mixon Denise St. Peter July 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-738-1 Ë|xHSKITCy067381zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religious Movements, Militancy, and Conflict in South Asia cases from india, pakistan, and afghanistan Authors Joy Aoun Liora Danan Sadika Hameed Robert D. Lamb Kathryn Mixon Denise St. Peter July 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

THE CASE for CHANGE a Review of Pakistan’S Anti-Terrorism Act of 1997

THE CASE FOR CHANGE A Review of Pakistan’s Anti-Terrorism Act of 1997 October 2013 A Report by the Research Society of International Law, Pakistan i PROJECT RESEARCHERS ISLAMABAD DIVISION Jamal Aziz Muhammad Oves Anwar LL.B (London), LL.M (UCL) LL.B (London), LL.M (SOAS), LL.M (Vienna), D.U. (Montpellier) Saad-ur-Rehman Khan Abid Rizvi LL.B (London), LL.M (Manchester) BA-LL.B (LUMS), LL.M (U.Penn) Aleena Zainab Alavi Zainab Mustafa LL.B (London), LL.M (Warwick) LL.B (London) LAHORE DIVISION Ali Sultan Amna Warsi J.D. (Virginia) LL.M (Punjab) Ayasha Warsi Moghees Khan LL.M (Punjab) LL.B (London), LL.M (Warwick) Mishael Qureshi LL.B (Lond.), LL.M (Sussex) INTERNS Muhammad Bin Majid Muhammad Abdul Ghani Awais Ahmad Khan Ghauri This material may not be copied, reproduced or transmitted in whole or in part without attribution to the Research Society of International Law (RSIL). Unless noted otherwise, all material is property of RSIL. Copyright © Research Society of International Law 2013. ii CONTENTS SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS .......................................................................................... IX CHAPTER ONE ....................................................................................................................................... 7 TERRORISM IN THE PAKISTANI CONTEXT .................................................................................. 7 1.1 TRENDS IN TERRORISM ........................................................................................................... 7 1.2 THE ANATOMY OF TERRORISM -

Tando Muhammad Khan

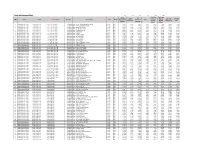

Tando Muhammad Khan 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010002 GBPS - YAR M. KANDRA@PIR BUX KANDRA Primary Boys 9,117 1,823 7,294 1,823 1,823 7,294 29,175 7,294 2 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010016 GBPS - YAR MUHAMMAD KANDRA Primary Boys 11,323 2,265 9,058 2,265 2,265 9,058 36,233 9,058 3 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010017 GBPS - KHUDA BUX GUMB Primary Boys 14,353 2,871 11,482 2,871 2,871 11,482 45,929 11,482 4 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010022 GBPS - ALAM KHAN TALPUR Primary Boys 44,542 8,908 35,634 8,908 8,908 35,634 142,535 35,634 5 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010025 GBPS - PALIO GHUMRANI Primary Boys 28,220 5,644 22,576 5,644 5,644 22,576 90,303 22,576 6 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010026 GBPS - KARIMABAD Primary Boys 28,690 5,738 22,952 5,738 5,738 22,952 91,808 22,952 7 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. -

List of Political Parties Enlisted on Our Record

List of Political Parties Enlisted on our Record SS.NN oo.. NNaammeoo fPP oolliittiiccaalPP aarrttyy NNaammeoo fPP aarrttyLL eeaaddeer DDeessiiggnnaattiioonn Address Baacha Khan Markaz, Pajaggi Road, 11 Awami National Party Asfandyar Wali Khan President Peshawar. Ph: 92-91-2246851-3, Fax:92-91- 2252406 No.1, National Park Road, Rawalpindi **** 88, 22 AAwwaammiQQ iiaaddaatPP aarrttyy GGeenneerraal(( RR)MM iirrzzaAA ssllaamBB eegg CChhaaiirrmmaann Race Course Road, St:3, Rawalpindi. Ph: 051- 5510761/5563309 Fax:5564244 Al-Jihad Trust Building, Block 52-B, Satellite 33 AAzzmmaatt--ee--IIssllaamMM oovveemmeenntt ZZaahheeeerr--uull--IIssllaamAA bbbbaassi(( MMaajjoorGG eenneerraall)) AAmmeeeer r Town, Rawalpindi.051-4419982 Headquarter Office, Balochistan National 44 BBaalloocchhiissttaanNN aattiioonnaalCC oonnggrreessss AAbbdduulHH aakkiimLL eehhrrii PPrreessiiddeenntt Congress Thana Road, Quetta. Ph:821201 22-G, Khayaban-e-Sahar, Defence Housing 55 BBaalloocchhiissttaanNN aattiioonnaal DDeemmooccrraattiic PPaarrttyy SSaarrddaar SSaannaauullllaah KKhhaanZZ eehhrrii PPrreessiiddeenntt Auithority, Karachi Istaqlal Building, Quarry Road, Quetta. 66 BBaalloocchhiissttaanNN aattiioonnaalPP aarrttyy SSaarrddaarAA kkhhtteerJJ aanMM eennggaall PPrreessiiddeenntt Phone:081-833869 Ashraf Market, Fawara Chowk, Abbottabad Markazi 77 HHaazzaarraQQ aauummiMM aahhaazz MM.AA ssiifMM aalliikk (Hazara) Ph: 0992-341465,330253, Fax: 0992- Chairman 335448 Cell 0332-5005448 Central Secretariat: Batala P.O Kahota, District 88 IIssllaammiSS iiaassiTT eehhrreeeekk -

Pakistan Courting the Abyss by Tilak Devasher

PAKISTAN Courting the Abyss TILAK DEVASHER To the memory of my mother Late Smt Kantaa Devasher, my father Late Air Vice Marshal C.G. Devasher PVSM, AVSM, and my brother Late Shri Vijay (‘Duke’) Devasher, IAS ‘Press on… Regardless’ Contents Preface Introduction I The Foundations 1 The Pakistan Movement 2 The Legacy II The Building Blocks 3 A Question of Identity and Ideology 4 The Provincial Dilemma III The Framework 5 The Army Has a Nation 6 Civil–Military Relations IV The Superstructure 7 Islamization and Growth of Sectarianism 8 Madrasas 9 Terrorism V The WEEP Analysis 10 Water: Running Dry 11 Education: An Emergency 12 Economy: Structural Weaknesses 13 Population: Reaping the Dividend VI Windows to the World 14 India: The Quest for Parity 15 Afghanistan: The Quest for Domination 16 China: The Quest for Succour 17 The United States: The Quest for Dependence VII Looking Inwards 18 Looking Inwards Conclusion Notes Index About the Book About the Author Copyright Preface Y fascination with Pakistan is not because I belong to a Partition family (though my wife’s family Mdoes); it is not even because of being a Punjabi. My interest in Pakistan was first aroused when, as a child, I used to hear stories from my late father, an air force officer, about two Pakistan air force officers. In undivided India they had been his flight commanders in the Royal Indian Air Force. They and my father had fought in World War II together, flying Hurricanes and Spitfires over Burma and also after the war. Both these officers later went on to head the Pakistan Air Force. -

Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: a Study Of

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 19, Issue 1 1995 Article 5 Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud∗ ∗ Copyright c 1995 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud Abstract Pakistan’s successive constitutions, which enumerate guaranteed fundamental rights and pro- vide for the separation of state power and judicial review, contemplate judicial protection of vul- nerable sections of society against unlawful executive and legislative actions. This Article focuses upon the remarkably divergent pronouncements of Pakistan’s judiciary regarding the religious status and freedom of religion of one particular religious minority, the Ahmadis. The superior judiciary of Pakistan has visited the issue of religious freedom for the Ahmadis repeatedly since the establishment of the State, each time with a different result. The point of departure for this ex- amination is furnished by the recent pronouncement of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (”Supreme Court” or “Court”) in Zaheeruddin v. State,’ wherein the Court decided that Ordinance XX of 1984 (”Ordinance XX” or ”Ordinance”), which amended Pakistan’s Penal Code to make the public prac- tice by the Ahmadis of their religion a crime, does not violate freedom of religion as mandated by the Pakistan Constitution. This Article argues that Zaheeruddin is at an impermissible variance with the implied covenant of freedom of religion between religious minorities and the Founding Fathers of Pakistan, the foundational constitutional jurisprudence of the country, and the dictates of international human rights law. -

The Thistle and the Drone

AKBAR AHMED HOW AMERICA’S WAR ON TERROR BECAME A GLOBAL WAR ON TRIBAL ISLAM n the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the United States declared war on terrorism. More than ten years later, the results are decidedly mixed. Here world-renowned author, diplomat, and scholar Akbar Ahmed reveals an important yet largely ignored result of this war: in many nations it has exacerbated the already broken relationship between central I governments and the largely rural Muslim tribal societies on the peripheries of both Muslim and non-Muslim nations. The center and the periphery are engaged in a mutually destructive civil war across the globe, a conflict that has been intensified by the war on terror. Conflicts between governments and tribal societies predate the war on terror in many regions, from South Asia to the Middle East to North Africa, pitting those in the centers of power against those who live in the outlying provinces. Akbar Ahmed’s unique study demonstrates that this conflict between the center and the periphery has entered a new and dangerous stage with U.S. involvement after 9/11 and the deployment of drones, in the hunt for al Qaeda, threatening the very existence of many tribal societies. American firepower and its vast anti-terror network have turned the war on terror into a global war on tribal Islam. And too often the victims are innocent children at school, women in their homes, workers simply trying to earn a living, and worshipers in their mosques. Bat- tered by military attacks or drone strikes one day and suicide bombers the next, the tribes bemoan, “Every day is like 9/11 for us.” In The Thistle and the Drone, the third vol- ume in Ahmed’s groundbreaking trilogy examin- ing relations between America and the Muslim world, the author draws on forty case studies representing the global span of Islam to demon- strate how the U.S. -

Politics and Pirs: the Nature of Sufi Political Engagement in 20Th and 21St Century Pakistan

Ethan Epping Politics and Pirs: The Nature of Sufi Political Engagement in 20th and 21st Century Pakistan By Ethan Epping On November 27th, 2010 a massive convoy set off from Islamabad. Tens of thousands of Muslims rode cars, buses, bicycles, and even walked the 300 kilometer journey to the city of Lahore. The purpose of this march was to draw attention to the recent rash of terrorism in the country, specifically the violent attacks on Sufi shrines throughout Pakistan. In particular, they sought to demonstrate to the government that the current lack of action was unacceptable. “Our caravans will reach Lahore,” declared one prominent organizer, “and when they do the government will see how powerful we are.”1 The Long March to Save Pakistan, as it has come to be known, was an initiative of the recently founded Sunni Ittehad Council (SIC), a growing coalition of Barelvi Muslims. The Barelvi movement is the largest Islamic sect within Pakistan, one that has been heavily influenced by Sufism throughout its history. It is Barelvis whose shrines and other religious institutions have come under assault as of late, both rhetorically and violently. As one might expect, they have taken a tough stance against such attacks: “These anti-state and anti-social elements brought a bad name to Islam and Pakistan,” declared Fazal Karim, the SIC chairman, “we will not remain silent and [we will] defend the prestige of our country.”2 The Long March is but one example of a new wave of Barelvi political activism that has arisen since the early 2000s. -

Balochistan Economic Report Background Paper on Social Structures and Migration

First Draft - Do Not Cite TA4757-PAK: BALOCHISTAN ECONOMIC REPORT Balochistan Economic Report Background Paper on Social Structures and Migration Haris Gazdar 28 February 2007 Collective for Social Science Research 173-I Block 2, PECHS, Karachi 75400, Pakistan [email protected] The author gratefully acknowledges research assistance provided by Azmat Ali Budhani, Sohail Javed, Hussain Bux Mallah, and Noorulain Masood. Irfan Khan provided guidance with resource material and advised on historical references. Introduction Compared with other provinces of Pakistan, and Pakistan taken as a whole, Balochistan’s economic and social development appears to face particularly daunting challenges. The province starts from a relatively low level – in terms of social achievements such as health, education and gender equity indicators, economic development and physical infrastructure. The fact that Balochistan covers nearly half of the land area of Pakistan while accounting for only a twentieth of the country’s population is a stark enough reminder that any understanding of the province’s economic and social development will need to pay attention to its geographical and demographic peculiarities. Indeed, remoteness, environmental fragility and geographical diversity might be viewed as defining the context of development in the province. But interestingly, Balochistan’s geography might also be its main economic resource. The low population density implies that the province enjoys a potentially high value of natural resources per person. The forbidding topography is home to rich mineral deposits – some of which have been explored and exploited while yet others remain to be put to economic use. The land mass of the province endows Pakistan with a strategic space that might shorten trade and travel costs between emerging economic regions.