A Tree Atop the Mountain: Mobad Manikan and the Elusive Promises of Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monthly Letter August 15 1936

2)*<¿<yt*d' Mi' cS)a¿u¿Ua£ &%¿éaSopÁ¿ea¿ &xaéébnt4' — ¿ r 9?l«K¿r 9 . August IS, 1936. ZOROASTER Dear Friend:- Zarathustrism, or Zoroastrianism as it is more be properly ordered because the Zend language is commonly called, was the ancient faith of the utterly extinct and the old records have found no Irano-Aryan peoples who at some remote period perpetuators in the modern world. migrated from India and civilized Persia, Media Greeks writers derive the term Zoroaster from a and other parts of ancient Chaldea. According to combination of syllables so that the word can have the earliest tradition the Magian Rites of the Per one of several meanings. First, a worshipper of the sians were established by the fire-prophet Zarathus stars. Second, the image of secret things. Third, a tra, but no reliable information is available as to the fashioner of images from hidden fire. Or most exact time of his life and ministry. He is variously probably, fourth, the son of the stars. placed from the first to the tenth millenium before The oldest of the Iranian books, called the Sesatir, Christ. This uncertainty results in part at least contains a collection of teachings and revelations from the destruction of the libraries of the Magian from fourteen of the ancient prophets of Iran, and philosophers by the armies of Alexander the Great. in this list Zoroaster stands thirteenth. It is not Zarathustra, in Greek Zoroaster, is a generic improbable that at some~prehistoric time a great name bestowed upon several initiated and divinely sage, an initiate of the original Mysteries of the illumined law-givers and religious reformers among Aryan Hindus, established the line of priest-prophets the Chaldeans. -

A Comparative Analysis of Educational Teaching in Shahnameh and Iliad Elhamshahverdi and Dr.Masoodsepahvandi Abstract

Date:12/1/18 A Comparative Analysis of Educational Teaching in Shahnameh and Iliad Elhamshahverdi and dr.Masoodsepahvandi Abstract Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and Homer's Iliad are among the first literary masterpieces of Iran and Greece. These teachings include the educational teachings of Zal and Roudabeh, and Paris and Helen. This paper presents a comparative look at the immortal effect of this Iranian poet with Homer's poem-- the Greek blind poet. In this comparison, using a content analysis method, the effects of the educational teachings of these two stories are extracted and expressed, The results of this study show that the human and universal educational teachings of Shahnameh are far more than that of Homer's Iliad. Keywords: teachings, education,analysis,Shahname,Iliad. Introduction The literature of every nation is a mirror of the entirety of thought, culture and customs of that nation, which can be expressed in elegance and artistic delicacy in many different ways. Shahnameh and Iliad both represent the literature of the two peoples of Iran and Greece, which contain moral values for the happiness of the individual and society. "The most obvious points of Shahnameh are its advice and many examples and moral commands. To do this, Ferdowsi has taken every opportunity and has made every event an excuse. Even kings and warriors are used for this purpose. "Comparative literature is also an important foundation for the exodus of indigenous literature from isolation, and it will be a part of the entire literary heritage of the world, exposed to thoughts and ideas, and is also capable of helping to identify contemplation legacies in the understanding and friendship of the various nations."(Ghanimi, 44: 1994) Epic literature includes poems that have a spiritual aspect, not an individual one. -

1 EBRU TURAN Fordham University-Rose Hill 441 E

Turan EBRU TURAN Fordham University-Rose Hill 441 E. Fordham Road, Dealy 620 Bronx NY, 10458 [email protected] (718-817-4528) EDUCATION University of Chicago, Ph.D., Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, March 2007 Bogazici University, B.A., Business Administration, 1997 Bogazici University, B.A., Economics, 1997 EMPLOYMENT Fordham University, History Department, Assistant Professor, Fall 2006-Present Courses Thought: Introduction to Middle East History, History of the Ottoman Empire (1300-1923), Religion and Politics in Islamic History University of Chicago, Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Graduate Lecturer, 2003-2005 Courses Thought: Ottoman Turkish I, II, III; History of the Ottoman Empire (1300-1700); Islamic Political Thought (700-1550) GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS Visiting Research Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, University of Texas-Austin, 2008-2009 Grant to attend the Folger Institute's Faculty Weekend Seminar,"Constantinople/Istanbul: Destination, Way-Station, City of Renegades," September 2007 Dissertation Write-Up Grant, Division of Humanities, Franke Institute for the Humanities, University of Chicago, 2005-2006 Grant to participate in Mellon Summer Institute in Italian Paleography Program, Newberry Library, Summer 2005 Turkish Studies Grant, University of Chicago, Summer 2004 Overseas Dissertation Research Fellowship, Division of Humanities, University of Chicago, 2003 American Research Institute in Turkey Dissertation Grant, 2002-2003 Turkish Studies Grant, University of Chicago, Summer 2002 Doctoral Fellow in Sawyer Seminar on Islam 1300-1600, Franke Institute for Humanities, University of Chicago, 2001-2002 Tuition and Stipend, Division of Humanities, University of Chicago, 1997-2001 PUBLICATIONS Articles: “Voice of Opposition in the Reign of Sultan Suleyman: The Case of Ibrahim Pasha (1523-1536),” in Studies on Istanbul and Beyond: The Freely Papers, Volume I, ed. -

Zarathushtra

366 THE OPEN COURT. in the restoration of a single roadway in Pekin, he would have earned for himself the respect and gratitude of all. His mistakes, however, were due to his past edu- cation. Nevertheless, his influence over the literati in China and elsewhere could not be disputed, and for such practical measures as above indicated we must look to some other Peter the Great or perhaps Napoleon. ZARATHUSHTRA. Professor A. V Williams Jackson, the Zend-Avesta Scholar of Columbia Uni- ity, New York, published in the January number of the Cosmopolitan an in- teresting illustrated article on Zarathushtra or Zoroaster, the prophet of Iran, born about 660 B. C. The canonical gospels tells us of the three Magi who came from the East to worship Christ and an apocryphal gospel adds the statement that they MISCELLANEOUS. 367 Takht-i Bostan Sculpture. The figure supposed to be Zarathushtra is the third figure in the row. It stands on a plant-like pedestal and the head is surrounded by a halo of rays, 368 THE OPEN COURT. came in compliance with a prophecy of Zoroaster. We quote the following passage which is a condensed statement of Zoroaster's life : "Tradition says that Zoroaster retired from the world when he came of age and that he lived for some years upon a remote mountain in the silence of the forest Idealised Portrait from a Sculpture Supposed to Represent ZarathushTra. (From Karaka's History of the Parsees.) or taking shelter in a lonely cave. It was the solemn stillness of such surroundings that lifted him into direct communion with God. -

Rostam As a Pre-Historic Iranian Hero Or the Shi'itic Missionary?

When Literature and Religion Intertwine: Rostam as a Pre-Historic Iranian Hero or the Shi’itic Missionary? Farzad Ghaemi Department of Persian Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Azadi Square, Mashhad, Khorasan Province 9177948883, Iran Email: [email protected] Azra Ghandeharion* (Corresponding Author) Department of English Studies, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Azadi Square, Mashhad, Khorasan Province 9177948883, Iran Email: [email protected] Abstract This article aims to show how Rostam, the legendary hero of Iranian mythology, have witnessed ideological alterations in the formation of Persian epic, Shahnameh. Among different oral and written Shahnamehs, this paper focuses on Asadi Shahnameh written during the 14th or 15th century. Though he is a pre- Islamic hero, Rostam and his tasks are changed to fit the ideological purposes of the poet’s time and place. A century later, under the influence of the state religion of Safavid Dynasty (1501–1736), Iranian pre-Islamic values underwent the process of Shi’itization. Scarcity of literature regarding the interpretation of Asadi Shahnameh and the unique position of this text in the realm of Persian epic are the reasons for our choice of scrutiny. In Asadi Shahnameh Rostam is both a national hero and a Shi’ite missionary. By meticulous textual and historical analysis, this article shows how Asadi unites seemingly rival subjects like Islam with Zoroastrianism, philosophy with religion, and heroism with mysticism. It is concluded that Asadi’s Rostam is the Shi’ite-Mystic version of Iranians’ popular hero who helps the cause of Shi’itic messianism and performs missionary tasks in both philosophic and practical levels. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

The Poet & the Poem 1 EPITOME of the SHAHNAMA Prologue 10 IT

CONTENTS List of Illustrations xiii Preface xvii Introduction: The Poet & the Poem 1 EPITOME OF THE SHAHNAMA Prologue 10 I THE PISHDADIAN DYNASTY 11 REIGN OF GAY UM ARTH 11 REIGN OF HUSHANG 11 REIGN OF TAHMURATH 12 REIGN OF JAMSHID 13 The Splendour of jamshid 13 The Tyranny of Zahhak 13 The Coming of Faridun 15 REIGN OF FARIDUN 16 Faridun & his Three Sons 16 REIGN OF MINUCHIHR 18 Zal & Rudaba 18 Birth & Early Exploits of Rustam 20 REIGNS OF NAWDAR, ZAV & GARSHASP 21 War with Turan 21 Robinson, B.W. digitalisiert durch: The Persian Book of Kings IDS Basel Bern 2014 viii THE PERSIAN BOOK OF KINGS II THE KAYANIAN DYNASTY 23 REIGN OF KAY QUBAD 23 Rustam's Quest for Kay Qubad 23 REIGN OF KAY KA'US 24 Disaster in Mazandaran 24 Rustam's Setzen Stages 26 Wars of Kay Ka'us 30 The Flying Machine 31 Rustam's Raid 32 Rustam & Suhrab 32 The Tragedy of Siyawush 36 Birth of Kay Khusraw 40 Revenge for Siyawush 41 Finding of Kay Khusraw 41 Abdication of Kay Ka'us 43 REIGN OF KAY KHUSRAW 43 Tragedy of Farud 43 Persian Reverses 45 Second Expedition: Continuing Reverses 46 Rustam to the Rescue 47 Rustam's Overthrow of Kamus, the Khaqan, and Others 48 Successful Termination of the Campaign 50 Rustam & the Demon Akwan 51 Bizhan & Manizha 53 Battie of the Twelve Rukhs 57 Afrasiyab's Last Campaign 60 Capture & Execution of Afrasiyab 63 The Last Days of Kay Khusraw 65 REIGN OF LUHRASP 65 Gushtasp in Rum 65 REIGN OF GUSHTASP 68 The Prophet Zoroaster 68 Vicissitudes of Isfandiyar 69 Isfandiyar's Seven Stages 70 Rustam & Isfandiyar 74 Death of Rustam 76 REIGN OF -

'The Conceits of Poetry': Firdausi's Shahnama

Mario Casari ‘The Conceits of Poetry’: Firdausi’s Shahnama and the discovery of Persian in early modern Europe The Muse of the Coming Age In one of his few meta-literary stories, written in 1861, the famous Danish fairy tale writer, Hans Christian Andersen, posed a question to the reader about the future of literature in the century to come. ‘The Muse of the Coming Age, whom our great grandchildren, or possibly a later generation still, but not ourselves, shall make acquaintance with, – how does she manifest herself ? What is her face and form? What is the burden of her song? Whose heart-strings shall she touch? To what summit shall she lift her century?’ Responding with the gaze of a Romantic writer, Anderson proposes a number of possible figures, at the crossroads of the poetic tradition and modern scientific prose. But what is certain to him is that the Muse ‘in the vast workshop of the present . is born, where steam exerts its sinews’; ‘The nurse has sung to her of Eivind Skalde-spiller and Firdusi, of the Minnesingers and what Heine, boyish-bold, sang from his very poet’s soul . ’. Thus, to Andersen, the Persian poet Firdausi was among the required body of knowledge for anyone who aimed at creating literature in the coming age; an age whose Muse was launched towards the future as a locomotive pushed by the force of steam. Andersen added, with emphasis and visionary passion: ‘Europe’s railways hedge old Asia’s fast- sealed culture-archives – the opposing streams of human culture meet! . -

Bahrām Čūbīn in Early Arabic and Persian Historiography – Why So Many Stories?

Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki Bahrām Čūbīn in Early Arabic and Persian Historiography – Why so many stories? Joonas Maristo Doctoral dissertation, to be presented for public discussion with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki in, Auditorium P673, Porthania, on the 20th of May, 2020 at 12 o’clock. Bahrām Čūbīn in Early Arabic and Persian Historiography – Why so many stories? Joonas Maristo University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts Doctoral Programme in History and Cultural Heritage Supervisors: Professor Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (University of Edinburgh) Docent Dr. Ilkka Lindstedt (University of Helsinki) Pre-examiners: Professor Sarah Bowen Savant (Aga Khan University) Professor A.C.S. Peacock (University of St Andrews) Opponent: Professor Sarah Bowen Savant (Aga Khan University) Custos Professor Hannu Juusola (University of Helsinki) The Faculty of Arts uses the Urkund system (plagiarism recognition) to examine all doctoral dissertations. ISBN 978-951-51-6052-2 (nid.) ISBN 978-951-51-6053-9 (PDF) Printed in Finland by Unigrafia Helsinki 2020 Abstract This doctoral dissertation discusses the transmission and evolution of Bahrām Čūbīn stories in early Arabic and Persian historiography in fourteen source texts. Bahrām Čūbīn (d. 591) was a historical figure and general in the Sasanian army during the reigns of Hurmuzd IV (r. 579–590) and Khusraw II (r. 591–628). The original stories were written in Middle Persian probably at the end of the 6th century or at the beginning of the 7th century and then translated into Arabic in the 8th century. Both the Pahlavi versions and early Arabic translations are irretrievably lost. -

Firdawsi's Shahnama in Its Ghaznavid Context A.C.S. Peacock1 Abstract

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository Firdawsi’s Shahnama in its Ghaznavid context A.C.S. Peacock1 Abstract Firdawsi’s Shahnama, the completion of which is traditionally to around 400/1010, is generally thought to have been a failure at first. It is said by both traditional accounts and much modern scholarship to have been rejected by its dedicatee Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna, and its contents of ancient Iranian legends, transmitted from earlier sources, are widely considered to have been out of step with the literary tastes of the Ghaznavid period. This article reassesses the reception of the Shahnama in the Ghaznavid period, arguing that evidence suggests neither its style nor contents were outdated, and that its tales of ancient Iranian heores had a great contemporary relevance in the context of the Ghaznavid court’s identification of the dynasty as the heir to ancient Iran. The extent to which Firdawsi can be shown to have relied on pre-Islamic sources is also reevaluated Key words Firdawsi – Shahnama – Ghaznavids – pre-Islamic Iran – Persian poetry The reception history of few books can be as well-known as the Shahnama: the allegedly cool reaction of sultan Mahmud of Ghazna (d. 421/1030) when presented with the work around the year 400/1010, and the biting satire on the ruler Firdawsi is claimed to have penned in response, together form part of the Shahnama legend.2 Firdawsi’s hostile reception by the rival poets of Ghazna, for instance, became a topic of miniature painting in manuscripts of the poem,3 and lines such as the satire were interpolated to underline the point.4 Today, the poem’s initial flop is usually taken for granted, and has been attributed to both its form and its contents, which are assumed to be purely antiquarian,5 bereft of any contemporary relevance. -

Additional Catalogue Entries

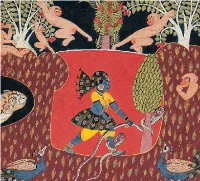

EPIC TALES from ANCIENT INDIA 1 2 EPIC TALES from ANCIENT INDIA 3 Note: need to add SDMA and Yale to title page This book is published in conjunction with the exhi- bition [Exhibition title], presented at [Museum] from [date] to [date]. Copyright © 2016 __________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, record- ing, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data [please provide or L|M will apply] ISBN 978-0-300-22372-9 Published by The San Diego Museum of Art Distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven and London 302 Temple Street P.O. Box 209040 New Haven, CT 06520-9040 yalebooks.com/art Produced by Lucia | Marquand, Seattle www.luciamarquand.com Edited by _______ Designed by Zach Hooker Typeset in Quadraat by Brynn Warriner Proofread by TK TK Color management by iocolor, Seattle Printed and bound in China by Artron Art Group 4 toc TK 5 Director’s Foreword The San Diego Museum of Art is blessed to have one of the great collections of Indian painting, the bequest of one of the great connoisseurs of our time, Edwin Binney 3rd. This collection of over 1,400 paintings has, over the years, provided material for a number of exhibitions that have examined the subject of Indian painting from many different angles, as only a collection of this breadth and depth can do. Our latest exhibition, Epic Tales from Ancient India, aims to approach the topic from yet another per- spective, by considering the paintings alongside the classics of literature that they illustrate. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Narrative and Iranian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Narrative and Iranian Identity in the New Persian Renaissance and the Later Perso-Islamicate World DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by Conrad Justin Harter Dissertation Committee: Professor Touraj Daryaee, Chair Professor Mark Andrew LeVine Professor Emeritus James Buchanan Given 2016 © 2016 Conrad Justin Harter DEDICATION To my friends and family, and most importantly, my wife Pamela ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2: Persian Histories in the 9th-12th Centuries CE 47 CHAPTER 3: Universal History, Geography, and Literature 100 CHAPTER 4: Ideological Aims and Regime Legitimation 145 CHAPTER 5: Use of Shahnama Throughout Time and Space 192 BIBLIOGRAPHY 240 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1 Map of Central Asia 5 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to all of the people who have made this possible, to those who have provided guidance both academic and personal, and to all those who have mentored me thus far in so many different ways. I would like to thank my advisor and dissertation chair, Professor Touraj Daryaee, for providing me with not only a place to study the Shahnama and Persianate culture and history at UC Irvine, but also with invaluable guidance while I was there. I would like to thank my other committee members, Professor Mark LeVine and Professor Emeritus James Given, for willing to sit on my committee and to read an entire dissertation focused on the history and literature of medieval Iran and Central Asia, even though their own interests and decades of academic research lay elsewhere.