Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monthly Letter August 15 1936

2)*<¿<yt*d' Mi' cS)a¿u¿Ua£ &%¿éaSopÁ¿ea¿ &xaéébnt4' — ¿ r 9?l«K¿r 9 . August IS, 1936. ZOROASTER Dear Friend:- Zarathustrism, or Zoroastrianism as it is more be properly ordered because the Zend language is commonly called, was the ancient faith of the utterly extinct and the old records have found no Irano-Aryan peoples who at some remote period perpetuators in the modern world. migrated from India and civilized Persia, Media Greeks writers derive the term Zoroaster from a and other parts of ancient Chaldea. According to combination of syllables so that the word can have the earliest tradition the Magian Rites of the Per one of several meanings. First, a worshipper of the sians were established by the fire-prophet Zarathus stars. Second, the image of secret things. Third, a tra, but no reliable information is available as to the fashioner of images from hidden fire. Or most exact time of his life and ministry. He is variously probably, fourth, the son of the stars. placed from the first to the tenth millenium before The oldest of the Iranian books, called the Sesatir, Christ. This uncertainty results in part at least contains a collection of teachings and revelations from the destruction of the libraries of the Magian from fourteen of the ancient prophets of Iran, and philosophers by the armies of Alexander the Great. in this list Zoroaster stands thirteenth. It is not Zarathustra, in Greek Zoroaster, is a generic improbable that at some~prehistoric time a great name bestowed upon several initiated and divinely sage, an initiate of the original Mysteries of the illumined law-givers and religious reformers among Aryan Hindus, established the line of priest-prophets the Chaldeans. -

A Comparative Analysis of Educational Teaching in Shahnameh and Iliad Elhamshahverdi and Dr.Masoodsepahvandi Abstract

Date:12/1/18 A Comparative Analysis of Educational Teaching in Shahnameh and Iliad Elhamshahverdi and dr.Masoodsepahvandi Abstract Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and Homer's Iliad are among the first literary masterpieces of Iran and Greece. These teachings include the educational teachings of Zal and Roudabeh, and Paris and Helen. This paper presents a comparative look at the immortal effect of this Iranian poet with Homer's poem-- the Greek blind poet. In this comparison, using a content analysis method, the effects of the educational teachings of these two stories are extracted and expressed, The results of this study show that the human and universal educational teachings of Shahnameh are far more than that of Homer's Iliad. Keywords: teachings, education,analysis,Shahname,Iliad. Introduction The literature of every nation is a mirror of the entirety of thought, culture and customs of that nation, which can be expressed in elegance and artistic delicacy in many different ways. Shahnameh and Iliad both represent the literature of the two peoples of Iran and Greece, which contain moral values for the happiness of the individual and society. "The most obvious points of Shahnameh are its advice and many examples and moral commands. To do this, Ferdowsi has taken every opportunity and has made every event an excuse. Even kings and warriors are used for this purpose. "Comparative literature is also an important foundation for the exodus of indigenous literature from isolation, and it will be a part of the entire literary heritage of the world, exposed to thoughts and ideas, and is also capable of helping to identify contemplation legacies in the understanding and friendship of the various nations."(Ghanimi, 44: 1994) Epic literature includes poems that have a spiritual aspect, not an individual one. -

1 EBRU TURAN Fordham University-Rose Hill 441 E

Turan EBRU TURAN Fordham University-Rose Hill 441 E. Fordham Road, Dealy 620 Bronx NY, 10458 [email protected] (718-817-4528) EDUCATION University of Chicago, Ph.D., Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, March 2007 Bogazici University, B.A., Business Administration, 1997 Bogazici University, B.A., Economics, 1997 EMPLOYMENT Fordham University, History Department, Assistant Professor, Fall 2006-Present Courses Thought: Introduction to Middle East History, History of the Ottoman Empire (1300-1923), Religion and Politics in Islamic History University of Chicago, Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Graduate Lecturer, 2003-2005 Courses Thought: Ottoman Turkish I, II, III; History of the Ottoman Empire (1300-1700); Islamic Political Thought (700-1550) GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS Visiting Research Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, University of Texas-Austin, 2008-2009 Grant to attend the Folger Institute's Faculty Weekend Seminar,"Constantinople/Istanbul: Destination, Way-Station, City of Renegades," September 2007 Dissertation Write-Up Grant, Division of Humanities, Franke Institute for the Humanities, University of Chicago, 2005-2006 Grant to participate in Mellon Summer Institute in Italian Paleography Program, Newberry Library, Summer 2005 Turkish Studies Grant, University of Chicago, Summer 2004 Overseas Dissertation Research Fellowship, Division of Humanities, University of Chicago, 2003 American Research Institute in Turkey Dissertation Grant, 2002-2003 Turkish Studies Grant, University of Chicago, Summer 2002 Doctoral Fellow in Sawyer Seminar on Islam 1300-1600, Franke Institute for Humanities, University of Chicago, 2001-2002 Tuition and Stipend, Division of Humanities, University of Chicago, 1997-2001 PUBLICATIONS Articles: “Voice of Opposition in the Reign of Sultan Suleyman: The Case of Ibrahim Pasha (1523-1536),” in Studies on Istanbul and Beyond: The Freely Papers, Volume I, ed. -

Zarathushtra

366 THE OPEN COURT. in the restoration of a single roadway in Pekin, he would have earned for himself the respect and gratitude of all. His mistakes, however, were due to his past edu- cation. Nevertheless, his influence over the literati in China and elsewhere could not be disputed, and for such practical measures as above indicated we must look to some other Peter the Great or perhaps Napoleon. ZARATHUSHTRA. Professor A. V Williams Jackson, the Zend-Avesta Scholar of Columbia Uni- ity, New York, published in the January number of the Cosmopolitan an in- teresting illustrated article on Zarathushtra or Zoroaster, the prophet of Iran, born about 660 B. C. The canonical gospels tells us of the three Magi who came from the East to worship Christ and an apocryphal gospel adds the statement that they MISCELLANEOUS. 367 Takht-i Bostan Sculpture. The figure supposed to be Zarathushtra is the third figure in the row. It stands on a plant-like pedestal and the head is surrounded by a halo of rays, 368 THE OPEN COURT. came in compliance with a prophecy of Zoroaster. We quote the following passage which is a condensed statement of Zoroaster's life : "Tradition says that Zoroaster retired from the world when he came of age and that he lived for some years upon a remote mountain in the silence of the forest Idealised Portrait from a Sculpture Supposed to Represent ZarathushTra. (From Karaka's History of the Parsees.) or taking shelter in a lonely cave. It was the solemn stillness of such surroundings that lifted him into direct communion with God. -

The Depiction of the Arsacid Dynasty in Medieval Armenian Historiography 207

Azat Bozoyan The Depiction of the ArsacidDynasty in Medieval Armenian Historiography Introduction The Arsacid, or Parthian, dynasty was foundedinthe 250s bce,detaching large ter- ritories from the Seleucid Kingdom which had been formed after the conquests of Alexander the Great.This dynasty ruled Persia for about half amillennium, until 226 ce,when Ardashir the Sasanian removed them from power.Under the Arsacid dynasty,Persia became Rome’smain rival in the East.Arsacid kingsset up theirrel- ativesinpositions of power in neighbouringstates, thus making them allies. After the fall of the Artaxiad dynasty in Armenia in 66 ce,Vologases IofParthia, in agree- ment with the RomanEmpire and the Armenian royal court,proclaimed his brother Tiridates king of Armenia. His dynasty ruled Armenia until 428 ce.Armenian histor- iographical sources, beginning in the fifth century,always reserved aspecial place for that dynasty. MovsēsXorenacʽi(Moses of Xoren), the ‘Father of Armenian historiography,’ at- tributed the origin of the Arsacids to the Artaxiad kingswho had ruled Armenia be- forehand. EarlyArmenian historiographic sources provide us with anumber of tes- timoniesregarding various representativesofthe Arsacid dynasty and their role in the spread of Christianity in Armenia. In Armenian, as well as in some Syriac histor- ical works,the origin of the Arsacids is related to King AbgarVof Edessa, known as the first king to officiallyadopt Christianity.Armenian and Byzantine historiograph- ical sources associate the adoption of Christianity as the state religion in Armenia with the Arsacid King Tiridates III. Gregory the Illuminator,who playedamajor role in the adoption of Christianity as Armenia’sstate religion and who even became widelyknown as the founder of the Armenian Church, belongstoanother branch of the samefamily. -

Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES General Editors Gillian Clark Andrew Louth THE OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES series includes scholarly volumes on the thought and history of the early Christian centuries. Covering a wide range of Greek, Latin, and Oriental sources, the books are of interest to theologians, ancient historians, and specialists in the classical and Jewish worlds. Titles in the series include: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and the Transformation of Divine Simplicity Andrew Radde-Gallwitz (2009) The Asceticism of Isaac of Nineveh Patrik Hagman (2010) Palladius of Helenopolis The Origenist Advocate Demetrios S. Katos (2011) Origen and Scripture The Contours of the Exegetical Life Peter Martens (2012) Activity and Participation in Late Antique and Early Christian Thought Torstein Theodor Tollefsen (2012) Irenaeus of Lyons and the Theology of the Holy Spirit Anthony Briggman (2012) Apophasis and Pseudonymity in Dionysius the Areopagite “No Longer I” Charles M. Stang (2012) Memory in Augustine’s Theological Anthropology Paige E. Hochschild (2012) Orosius and the Rhetoric of History Peter Van Nuffelen (2012) Drama of the Divine Economy Creator and Creation in Early Christian Theology and Piety Paul M. Blowers (2012) Embodiment and Virtue in Gregory of Nyssa Hans Boersma (2013) The Chronicle of Seert Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq PHILIP WOOD 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Philip Wood 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. -

Rostam As a Pre-Historic Iranian Hero Or the Shi'itic Missionary?

When Literature and Religion Intertwine: Rostam as a Pre-Historic Iranian Hero or the Shi’itic Missionary? Farzad Ghaemi Department of Persian Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Azadi Square, Mashhad, Khorasan Province 9177948883, Iran Email: [email protected] Azra Ghandeharion* (Corresponding Author) Department of English Studies, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Azadi Square, Mashhad, Khorasan Province 9177948883, Iran Email: [email protected] Abstract This article aims to show how Rostam, the legendary hero of Iranian mythology, have witnessed ideological alterations in the formation of Persian epic, Shahnameh. Among different oral and written Shahnamehs, this paper focuses on Asadi Shahnameh written during the 14th or 15th century. Though he is a pre- Islamic hero, Rostam and his tasks are changed to fit the ideological purposes of the poet’s time and place. A century later, under the influence of the state religion of Safavid Dynasty (1501–1736), Iranian pre-Islamic values underwent the process of Shi’itization. Scarcity of literature regarding the interpretation of Asadi Shahnameh and the unique position of this text in the realm of Persian epic are the reasons for our choice of scrutiny. In Asadi Shahnameh Rostam is both a national hero and a Shi’ite missionary. By meticulous textual and historical analysis, this article shows how Asadi unites seemingly rival subjects like Islam with Zoroastrianism, philosophy with religion, and heroism with mysticism. It is concluded that Asadi’s Rostam is the Shi’ite-Mystic version of Iranians’ popular hero who helps the cause of Shi’itic messianism and performs missionary tasks in both philosophic and practical levels. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

Pu1cheria's Crusade A.D. 421-22 and the Ideology of Imperial Victory Kenneth G

Pulcheria's Crusade A.D. 421-22 and the Ideology of Imperial Victory Holum, Kenneth G Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1977; 18, 2; Periodicals Archive Online pg. 153 Pu1cheria's Crusade A.D. 421-22 and the Ideology of Imperial Victory Kenneth G. Holum .. 'EST qu'en effet l'empereur byzantin, comme son ancetre Cl'imperator des derniers siecles de Rome, est essentiellement, aux yeux de son peuple, un maitre victorieux." This pointed definition (from the pen of Jean Gagel) underscores a theme of imperial ideology which receives such insistent emphasis in the offi cial art, ceremonial and panegyric of late antiquity that it must correspond to a chilling reality. The defeat of an emperor threatened not only the integrity of the frontiers but internal stability as well and the ascendancy of the emperor and his friends. Conversely, if a weak emperor could claim a dramatic victory, he might establish a more effective hold on the imperial power. In A.D. 420-22 this inner logic of Roman absolutism led to innovations in imperial ideology and to a crusade against Persia, with implications which have escaped the attention of scholars. The unwarlike Theodosius II made war not to defend the Empire but to become "master of victory," and, as will be seen, to strengthen the dynastic pretensions of his sister Pulcheria Augusta. I The numismatic evidence is crucial. Between 420 and early 422 the mint of Constantinople initiated a strikingly new victory type, the much-discussed 'Long-Cross Solidi' (PLATE 2):2 Obverse AELPVLCH-ERIAAVG Bust right, diademed, crowned by a hand Reverse VOTXX MVLTXXX~ Victory standing left, holding a long jeweled cross, CONOB in the exergue 1 "l:Taupoc VLK01TOLbC: la victoire imperiale dans l'empire chretien," Revue d'histoire et de philosophie religieuses 13 (1933) 372. -

Bahrām Čūbīn in Early Arabic and Persian Historiography – Why So Many Stories?

Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki Bahrām Čūbīn in Early Arabic and Persian Historiography – Why so many stories? Joonas Maristo Doctoral dissertation, to be presented for public discussion with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki in, Auditorium P673, Porthania, on the 20th of May, 2020 at 12 o’clock. Bahrām Čūbīn in Early Arabic and Persian Historiography – Why so many stories? Joonas Maristo University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts Doctoral Programme in History and Cultural Heritage Supervisors: Professor Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (University of Edinburgh) Docent Dr. Ilkka Lindstedt (University of Helsinki) Pre-examiners: Professor Sarah Bowen Savant (Aga Khan University) Professor A.C.S. Peacock (University of St Andrews) Opponent: Professor Sarah Bowen Savant (Aga Khan University) Custos Professor Hannu Juusola (University of Helsinki) The Faculty of Arts uses the Urkund system (plagiarism recognition) to examine all doctoral dissertations. ISBN 978-951-51-6052-2 (nid.) ISBN 978-951-51-6053-9 (PDF) Printed in Finland by Unigrafia Helsinki 2020 Abstract This doctoral dissertation discusses the transmission and evolution of Bahrām Čūbīn stories in early Arabic and Persian historiography in fourteen source texts. Bahrām Čūbīn (d. 591) was a historical figure and general in the Sasanian army during the reigns of Hurmuzd IV (r. 579–590) and Khusraw II (r. 591–628). The original stories were written in Middle Persian probably at the end of the 6th century or at the beginning of the 7th century and then translated into Arabic in the 8th century. Both the Pahlavi versions and early Arabic translations are irretrievably lost. -

Additional Catalogue Entries

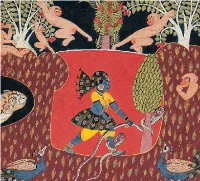

EPIC TALES from ANCIENT INDIA 1 2 EPIC TALES from ANCIENT INDIA 3 Note: need to add SDMA and Yale to title page This book is published in conjunction with the exhi- bition [Exhibition title], presented at [Museum] from [date] to [date]. Copyright © 2016 __________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, record- ing, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data [please provide or L|M will apply] ISBN 978-0-300-22372-9 Published by The San Diego Museum of Art Distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven and London 302 Temple Street P.O. Box 209040 New Haven, CT 06520-9040 yalebooks.com/art Produced by Lucia | Marquand, Seattle www.luciamarquand.com Edited by _______ Designed by Zach Hooker Typeset in Quadraat by Brynn Warriner Proofread by TK TK Color management by iocolor, Seattle Printed and bound in China by Artron Art Group 4 toc TK 5 Director’s Foreword The San Diego Museum of Art is blessed to have one of the great collections of Indian painting, the bequest of one of the great connoisseurs of our time, Edwin Binney 3rd. This collection of over 1,400 paintings has, over the years, provided material for a number of exhibitions that have examined the subject of Indian painting from many different angles, as only a collection of this breadth and depth can do. Our latest exhibition, Epic Tales from Ancient India, aims to approach the topic from yet another per- spective, by considering the paintings alongside the classics of literature that they illustrate. -

The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, 395-600 CE

The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity AD 395–600 The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity AD 395–600 deals with the exciting period commonly known as ‘late antiquity’ – the fifth and sixth centuries. The Roman empire in the west was splitting into separate Germanic kingdoms, while the Near East, still under Roman rule from Constantinople, maintained a dense population and flourishing urban culture until the Persian and Arab invasions of the early seventh century. Averil Cameron places her emphasis on the material and literary evidence for cultural change and offers a new and original challenge to traditional assumptions of ‘decline and fall’ and ‘the end of antiquity’. The book draws on the recent spate of scholarship on this period to discuss in detail such controversial issues as the effectiveness of the late Roman army, the late antique city and the nature of economic exchange and cultural life. With its extensive annotation, it provides a lively, and often critical introduction to earlier approaches to the period, from Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire to the present day. No existing book in English provides so detailed or up-to-date an introduction to the history of both halves of the empire in this crucial period, or discusses existing views in such a challenging way. Averil Cameron is a leading specialist on late antiquity, having written about the period and taught it for many years. This book has much to say to historians of all periods. It will be particularly welcomed by teachers and students of both ancient and medieval history.