Mitt's '109 by Kenneth Wallace Fields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 | Issue #27

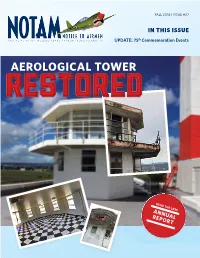

FALL 2016 | ISSUE #27 IN THIS ISSUE UPDATE: 75th Commemoration Events AEROLOGICAL TOWER restored READ THE 2015 ANNUAL REPORT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S REPORT December evokes many special sounds, sights, and memories all around. The month is doubly auspicious, as it includes honoring my wife and mother on their birthdays, and of course, the celebration of Christmas. It also marks our Museum’s anniversary, coinciding with the season when thousands arrive in Hawaii to escape the winter cold. This December, however, is even more special. It’s the 75th Commemoration of the 1941 attack that prompted the United States to enter the battle for freedom. We are deeply engaged to mark the 75th anniversary. Our December 3rd Saturday night gala in Hangar 79 will kick off more than a week of activities and events. And it’s the Museum’s 10th anniversary as well! Our historic Hangar 79, which survived the 1941 attack, houses a collection of remarkable vintage aircraft flown by combat heroes. Last year, the Japanese Nakajima B5N2 Type 97 Torpedo Bomber “Kate” and the OH-58E Kiowa arrived, and this year, the F-16A Fighting Falcon and the AT-6/SNJ Texan joined our ranks. Ken DeHoff During our gala, the Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress and Kate will be on display in our Lt. Executive Director of Operations Ted Shealy Restoration Shop as in-progress exhibits. We take the opportunity to share the importance of these war-birds and the ongoing work on each. We present the Museum as a living and exciting place to visit and work. -

A PUBLICATION of the INTERNATIONAL GROUP for HISTORIC AIRCRAFT RECOVERY Spring 1988 Vol. 4 No. 1

TIGHAR TRACKS A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR HISTORIC AIRCRAFT RECOVERY Spring 1988 Vol. 4 No. 1 Contents SPRING 1988 Overview ..................................................................... 3 ... that they might escape the teeth of time Dear TIGHAR ............................................................ 4 and the hands of mistaken zeal. Project Midnight Ghost ............................................... 6 —JOHN AUBREY B-17E Recovery Expedition ....................................... 14 1660 Operation Sepulchre .................................................. 15 Members’ Exploits ..................................................... 16 TIGHAR (pronounced “tiger”) is the acronym for The Interna- Rumor Mill ............................................................... 17 tional Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery, a non-profit founda- tion dedicated to promoting responsible aviation archeology and Aviation Archeologist ................................................. 18 historic preservation. TIGHAR was incorporated in January 1985 Strictly Business ......................................................... 19 and recognized as a 501(c)(3) public charity by the IRS in Novem- ber of that year. Offices are maintained in Middletown, Delaware COVER: Preserved by the environment which imprisons on the Summit Airport, and staffed by the foundation’s Executive it, the world’s oldest complete and original B-17 Flying Committee, Richard E. Gillespie, Executive Director, and Patricia Fortress waits patiently in the -

Quizinfo Alpha

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Sort – Book Title Alpha Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 17351EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.3 1.0 17352EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 7.9 1.0 17353EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.1 1.0 17354EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.5 1.0 17355EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 7.7 1.0 17356EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.7 1.0 17357EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Sum Bob Italia 7.0 1.0 17358EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Win Bob Italia 7.4 1.0 18751EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 3.9 5.0 80179EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Teacher Lee Wardlaw 4.4 8.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 6.8 2.0 8251EN 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair 4.4 1.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.1 3.0 48781EN The 1940s: Secrets Dorothy/Tom Hooble 5.0 4.0 48783EN The 1960s: Rebels Dorothy/Tom Hooble 5.0 4.0 30629EN 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola 4.4 1.0 109710EN A 3-D Birthday Party Ellen B. Senisi 2.9 0.5 54379EN 4 Give & 4 Get Brown/Holl 4.5 4.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 5.2 5.0 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups A.K. Donahue 4.5 1.0 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 3.9 1.0 57142EN 7 x 9 = Trouble! Claudia Mills 4.3 1.0 76205EN 97 Ways to Train a Dragon Kate McMullan 3.3 2.0 80599EN A-10 Thunderbolt II Lynn M. -

Volume 19 Number 5 (Journal 680) May, 2016

IN THIS ISSUE President’s Message Page 3 Articles Page 19-43 Vice President’s Message Page 4 Letters Page 44-48 About the Cover Page 5 In Memoriam Page 48-50 Local Reports Page 7-16 Calendar Page 52 Volume 19 Number 5 (Journal 680) May, 2016 —— OFFICERS —— President Emeritus: The late Captain George Howson President: Cort de Peyster………………………………………...916-335-5269……………………………………………... [email protected] Vice President: Bob Engelman…………………………………..954-436-3400…………………………………………[email protected] Sec/Treas: Leon Scarbrough………………………………………707-938-7324……………………………………………[email protected] Membership Larry Whyman………………………………………707-996-9312…………………………………………[email protected] —— BOARD OF DIRECTORS —— President - Cort de Peyster — Vice President - Bob Engelman — Secretary Treasurer - Leon Scarbrough Rich Bouska, Phyllis Cleveland, Sam Cramb, Ron Jersey, Milt Jines, Walt Ramseur, Jonathan Rowbottom Bill Smith, Cleve Spring, Larry Wright —— COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN —— Cruise Coordinator…………………………………….. Rich Bouska ........................ [email protected] Eblast Chairman……………………………………….. Phyllis Cleveland ............. [email protected] RUPANEWS Manager/Editor………………………… Cleve Spring ............................. [email protected] Website Coordinator………………………………….. Jon Rowbottom ................... rowbottom0@aol,com Widows Coordinator…………………………………... Carol Morgan ................. [email protected] Patti Melin ................................... [email protected] RUPA WEBSITE………………………………………………………..……………….http://www.rupa.org —— AREA REPRESENTATIVES -

PAM Spring2013nl.Pdf

NEWSLETTER SPRING 2013 | ISSUE #18 Photo Credit: Oliver, Frederique. Swamp Ghosts. 2007. Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. Smithsonianmag.com. Web. 25 April 2013. Pictured, model showing a sample plan for the Swamp Ghost! One of the most talked about artifacts of American aviation Over the next 30 plus years, Alfred Hagen of Aero Archaeology history, the 1941 Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress bomber, serial attempted to recover the bomber. Finally, after years of number 41-2446 (aka Swamp Ghost), now makes its home at negotiations, John Tallichet, Alfred Hagen, and the Swamp Pacific Aviation Museum Pearl Harbor! Ghost Salvage Team were cleared to return this amazing artifact On February 22, 1942, aircraft 41-2446, along with four other to the United States in 2010. B-17s, took off from Townsville, Australia on a Navy mission to During this past year, Pacific Aviation Museum successfully attack ships at Rafael, a harbor the Imperial Japanese Navy held negotiated with the owners for the acquisition of Swamp Ghost, in New Britain. This flight was the first American heavy bomber and Matson Navigation brought the aircraft from Chino to offensive raid of World War II. Hawaii on April 2, 2013. Unfortunately, 41-2446 did not make it back. Having sustained Swamp Ghost will be one of the crown jewels in the Museum’s damage from enemy fire, it ran out of fuel and crash-landed in the aircraft collection, with plans to restore this aircraft to static exhibit. remote, primitive Agaiambo swamp on the north coast of Papua While funds are raised for restoration, Swamp Ghost will be on New Guinea. -

Legendary Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress A.K.A. “Swamp Ghost” Arrived Today, April 10 at Pacific Aviation Museum Pearl Harbor

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 10, 2013 Contact: Anne Murata, Director of Marketing 808-441-1013; 808-375-9577 (cell) [email protected] James Koivunen, Marketing Coordinator 808-441-1011; 808-264-4555 (cell) [email protected] Follow us on Facebook, Flickr, YouTube, and on Twitter @PacificAviation Legendary Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress a.k.a. “Swamp Ghost” Arrived Today, April 10 At Pacific Aviation Museum Pearl Harbor Honolulu, HI – One of the most talked about artifacts of American aviation history--the Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress bomber #41-2446 “Swamp Ghost”—arrived at Pacific Aviation Museum Pearl Harbor, today, Wednesday, April 10, 2013. The Matson shipment trucks began arriving at 9am. Matson shipped the aircraft, in pieces, from California to the Museum. The remarkable story of this WWII aircraft has been featured in numerous media, including National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, L.A. Daily News, and Smithsonian magazine. B-17E 41-2446 was one of the bombers in the Kangaroo Squadron stationed in Townsville, Australia. It was to have been one of the B- 17s in the flight that made it to Hickam Army Air Field during the December 7, 1941 attack. It was delayed due to engine problems but flew to Hickam on December 17 and then leapfrogged its way to Townsville, Australia. On the night of February 22, 1942, five B-17s took off from Townsville with the mission of attacking ships at Rabaul, a harbor of Japanese-held New Britain. The mission was the first American heavy bomber offensive raid of World War II. Unfortunately, this B-17 never made it back. -

THE 99Th Bomb Group Historical Society Newsletter Vol. 1 O No. 2

THE 99th Bomb Group Historical Society Newsletter Vol. 1 No. o 2 Mar. 1 1990 SOCIETY OFFICERS, 1989-1990 PRESIDENT - BILL SMALLWOOD VICE-PRESIDENT - FRED HUEGLIN TREASURER - WALTER BUTLER HISTORIAN - GEORGE F. COEN SECRETARY - H.E.CHRISTIANSEN EDITOR - GEORGE F. COEN � THE PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Dear George: It was good to note the presence of plenty of "meat" in the January, 1990 Hewsletter, despite the shorter number of pages- (good for the budget), a tribute to your organ izational skills, I have gone over a whole series of these publications and have found a wealth of 99th history. My copies go back to Dec. 1980, the issue in which you wrote to Bill Holt about how you got into "the reunion business." Inclusion in this latest Newsletter of part of the war diary of Squadron J47, when we were based at Oudna, confirms that we must have shared a base with a B-24 F,roup. This is something I had hoped to confirm. I hope everyone will take note of Joe Kenney's message in "Chaplain's Corner" that anyone who has input about a ninety niner who has just passed away is welcome to send it along to Joe, that all of us can share it. Chris c. has been working away at plans for April's reunion in Huntsville. Applications are rolling in, and noone should wait till the last minute. As you will note Chris has help now from Herb Holdsambeck on golfinf activities; there are four courses in the area. Best Ree;ards --;;=. ·,·..�· ("'"• . (�- 2 3 4520 Panorama Drive SE, Huntsville, AL 35801-1211 Phone 205-534-8646 1 February 1990 IJEAR GEORGE, IT WAS GOOD TO GET TO TALK TO YOU TUESDAY NIGHT. -

Model Builder July 1989

Βϋ JU LY 1989 ICD 08545 U.S.A. $2.95 Canada $3.95 volume 19, number 209 WORLD'S MOST COMPLETE MODEL PUBLICATION INSIDE: Plans for a ‘U’tM M & S a fiS F 00 0 74820 08545 ,n5 Play! If you fly a .40 or .46-sized plane, you can enjoy the classic features of O .S. SF engines with the bonus of a factory pre-set pump system. With Schnuerle porting, a double ball-bearing supported crankshaft, single-piece crankcase, and expansion muffler, the new .46 S F ABC-P is as forceful as you'd expect any O.S. engine to be. Outfitted with the newly-designed 46 The .46 SF ABC-P’s new pump For larger models, the Pump System, it’s the power you've asked for, and more. and carburetor maximize fuel .61 RF ABC-P offers power The 46 Pump System yields optimum pressurized fuel efficiency. plus unequalled reliability. flow, resulting in greater consistency of operation and unequalled reliability, even during the most demanding maneuvers. The pump is preset at the factory and requires no adjust ment. Together with a specially- designed carburetor, the 46 Pump System makes the new .46 SF ABC-P the ideal match for your DBENGINES power-hungry plane. Whether you're flying a .40 or . 60-size model, O.S. has the answer for your power DISTRIBUTED TO LEADING RETAILERS needs. An O.S. SF engine is ready to push your expectations of performance to new N ATIO N W ID E E X C L U S IV E L Y T H R O U G H heights. -

The Swamp Ghost Press Contact Justin Taylan [email protected] (Port Moresby) 321-5839 (USA) 1-310-927-7864

The Swamp Ghost Press Contact www.TheSwampGhost.com Justin Taylan [email protected] (Port Moresby) 321-5839 (USA) 1-310-927-7864 One-Liner The true story of an intact World War II bomber that landed in a New Guinea swamp, and exists to this day. Documentary Summary Know as ‘The Swamp Ghost’, this American B-17 Flying Fortress bomber exists in a remote swamp in northern New Guinea. When it was rediscovered in the early 1970s, photographs of this intact and complete bomber captured the world’s attention. Despite hopes for salvage, no one has ever undertaken a study of the history or comprehensive documentation of the wreck… until now. Join videographer and historian, Justin Taylan on a quest to find the bomber and experience this ‘ghost’ himself. After several attempts, Taylan and fellow historians John Douglas and Michael Claringbould are find ‘The Swamp Ghost’. ‘The Swamp Ghost’ DVD tells the history of this aircraft, from the day it was built until it force landed during America’s first bombing mission in the New Guinea theater. Flying from Australia on a mission over 2,200 miles unescorted, it attacked Japanese forces occupying Rabaul. Over the target, the crew elected to go around on a second pass after a bomb bay malfunction. Intercepted by Japanese fighters and hit with anti-aircraft fire, they fought their way homeward. Low on fuel, the bomber force landed in a swamp. After a six week trek, all returned to their unit with the help of local people and the Resident Magistrate. Today, the bomber is the last intact World War II aircraft wreck on land left in the world. -

Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

Last updated 1 July 2021 ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| BOEING B-17 FLYING FORTRESS ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| 1963 Model 299 NX13372 Boeing Aircraft Co, Seattle WA: ff 28.7.35 XB-17 crashed Wright Field, Dayton OH 30.10.35 ________________________________________________________________________________________ 2125 • B-17D 40-3097 19th BG, Philippines: BOC 25.4.41 RB-17D (Ole Betsy, later The Swoose: used as personal aircraft of General George H. Brett, Australia and South America 42/44) City of Los Angeles CA: displ. Mines Field CA 6.4.46/49 Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 3.49/61 (del. Park Ridge IL .49 for storage, del. Pyote TX .50 for storage 50/53, del. Andrews AFB .53, open storage 53/61) NASM Store, Silver Hill MD: arr, stored dism. 4.61/08 USAFM, Wright Patterson AFB Dayton OH 7.08/19 (moved in sections 7.08 to Wright Patterson AFB, complete fuselage moved 11.7.08, under rest. 10/12) (exchange for USAFM’s B-17 “Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby”) ________________________________________________________________________________________ 2249 B-17E 41-2438 (to RCAF as 9206): BOC 15.12.43: SOC 27.12.46 LV-RTO Carlos J. Perez de Villa, Moron .47/48 (arr. Argentina 3.47 on -

Know the Past ...Shape the Future

FALL 2019 - Volume 66, Number 3 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

Biggest Little Airshow Honoring the Anniversary of the Battle of Midway

SPRING 2016 | ISSUE #26 IN THIS ISSUE 75th Commemoration Dinner Disney’s “Swamp Ghost” Biggest Little Airshow Honoring The Anniversary of the Battle of Midway Inside… PACIFIC AVIATION MUSEUM PEARL HARBOR Helping to Plan the 75th Commemoration of the Attack on Pearl Harbor EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S REPORT We welcome 2016 with a host of activities and projects. Yes, this is the 10th anniversary of Pacific Aviation Museum Pearl Harbor. It is also the 75th Commemoration of our reason for being, why the Museum is here on this historic site — the attack on Pearl Harbor. It is fitting that we spend this year looking back at 1941 and the historical moments leading up to the U.S. involvement in World War II. Conflict was raging across Europe and China. At home, my father was a young sergeant in the Arizona National Guard. His Quarter Master unit was activated in August 1940 and sent to Texas. He had just graduated from Arizona State University and wanted to be a pilot. Manufacturing in the U.S. had already shifted from building cars to airplanes, like the Curtiss P-40, Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber and the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Ford Island was an active seaplane port with Consolidated PBY Catalinas, Grumman Ducks, and Sikorsky Floatplanes in the air, daily. The Imperial Japanese Army Air Service and the Imperial Navy were flying new aircraft like the Mitsubishi A6M2 “Zeke”/“Zero,” Ken DeHoff Executive Director of Operations the Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” torpedo bomber, and the Aichi D3A “Val” dive bomber — all to be seen later, in Hawaii, on December 7, 1941.