Chapter 2 Dark Matter PAD.D (Grin of the Archive)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Edith Wyle, 1993 March 9-September 7

Oral history interview with Edith Wyle, 1993 March 9-September 7 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview EW: EDITH WYLE SE: SHARON EMANUELLI SE: This is an interview for the Archives of American Art, the Smithsonian Institution. The interview is with Edith R. Wyle, on March 9th, Tuesday, 1993, at Mrs. Wyle's home in the Brentwood area of Los Angeles. The interviewer is Sharon K. Emanuelli. This is Tape 1, Side A. Okay, Edith, we're going to start talking about your early family background. EW: Okay. SE: What's your birth date and place of birth? EW: Place of birth, San Francisco. Birth date, are you ready for this? April 21st, 1918-though next to Beatrice [Wood-Ed.] that doesn't seem so old. SE: No, she's having her 100th birthday, isn't she? EW: Right. SE: Tell me about your grandparents. I guess it's your maternal grandparents that are especially interesting? EW: No, they all were. I mean, if you'd call that interesting. They were all anarchists. They came from Russia. SE: Together? All together? EW: No, but they knew each other. There was a group of Russians-Lithuanians and Russians-who were all revolutionaries that came over here from Russia, and they considered themselves intellectuals and they really were self-educated, but they were very learned. -

Feminist Art, the Women's Movement, and History

Working Women’s Menu, Women in Their Workplaces Conference, Los Angeles, CA. Pictured l to r: Anne Mavor, Jerri Allyn, Chutney Gunderson, Arlene Raven; photo credit: The Waitresses 70 THE WAITRESSES UNPEELED In the Name of Love: Feminist Art, the Women’s Movement and History By Michelle Moravec This linking of past and future, through the mediation of an artist/historian striving for change in the name of love, is one sort of “radical limit” for history. 1 The above quote comes from an exchange between the documentary videomaker, film producer, and professor Alexandra Juhasz and the critic Antoinette Burton. This incredibly poignant article, itself a collaboration in the form of a conversation about the idea of women’s collaborative art, neatly joins the strands I want to braid together in this piece about The Waitresses. Juhasz and Burton’s conversation is at once a meditation of the function of political art, the role of history in documenting, sustaining and perhaps transforming those movements, and the influence gender has on these constructions. Both women are acutely aware of the limitations of a socially engaged history, particularly one that seeks to create change both in the writing of history, but also in society itself. In the case of Juhasz’s work on communities around AIDS, the limitation she references in the above quote is that the movement cannot forestall the inevitable death of many of its members. In this piece, I want to explore the “radical limit” that exists within the historiography of the women’s movement, although in its case it is a moribund narrative that threatens to trap the women’s movement, fixed forever like an insect under amber. -

Cheri Gaulke and Sue Maberry Construct a Visual Narrative of the Lesbian Family

The Home that the Woman’s Building Built: Cheri Gaulke and Sue Maberry Construct a Visual Narrative of the Lesbian Family ANNE SWARTZ Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, Georgia, USA Artists Cheri Gaulke and Sue Maberry’s feminist activism learned at the Woman’s Building, combined with their lesbianism, radi- calized them to create ongoing documentation of their family. This article examines how Gaulke has intertwined her domestic, private imagery and narrative with her artistic, public work in a way that reveals a useful mode for her to examine the range of experiences as lesbian, parent, and artist. Thus, these two bodies of work co-exist and inform each other in her oeuvre and in her art with partner Maberry. They have created a kind of sexualized display sometimes inverting heteronormative conventions while other times presenting the family as a single unit, transgressive in its happiness and unity. KEYWORDS lesbians, photography, families, parenting INTRODUCTION In 1996, when I first taught the class “Women in Art,” a revisionist ap- proach to the entire history of Western art examining representations, artists, and patrons, I wanted the class to eliminate racial, ethnic, social, and sexual barriers in terms of what the students would be discussing and studying. The class was difficult to teach because enough revisionist scholarship—Whitney Chadwick, Norma Broude, and Mary Garrard wrote the textbooks I used—existed to make the topic available for discussion and analysis, but not enough to show the students a range of artists. Third-wave feminism was just gathering steam by the mid-1990s and the great num- bers of lesbian artists who would soon burst on the scene or start getting I am grateful to the artists for their support of this project and to Margo Thompson for her editorial guidance. -

Oral History Interview with Suzanne Lacy, 1990 Mar. 16-Sept. 27

Oral history interview with Suzanne Lacy, 1990 Mar. 16-Sept. 27 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Suzanne Lacy on March 16, 1990. The interview took place in Berkeley, California, and was conducted by Moira Roth for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview has been extensively edited for clarification by the artist, resulting in a document that departs significantly from the tape recording, but that results in a far more usable document than the original transcript. —Ed. Interview [ Tape 1, side A (30-minute tape sides)] MOIRA ROTH: March 16, 1990, Suzanne Lacy, interviewed by Moira Roth, Berkeley, California, for the Archives of American Art. Could we begin with your birth in Fresno? SUZANNE LACY: We could, except I wasn’t born in Fresno. [laughs] I was born in Wasco, California. Wasco is a farming community near Bakersfield in the San Joaquin Valley. There were about six thousand people in town. I was born in 1945 at the close of the war. My father [Larry Lacy—SL], who was in the military, came home about nine months after I was born. My brother was born two years after, and then fifteen years later I had a sister— one of those “accidental” midlife births. -

Reading Contemporary Performance

Reading Contemporary Performance As the nature of contemporary performance continues to expand into new forms, genres and media, it requires an increasingly diverse vocabulary. Reading Contemporary Performance provides students, critics and creators with a rich understanding of the key terms and ideas that are central to any discussion of this evolving theatricality. Specially commissioned entries from a wealth of contributors map out the many and varied ways of discussing performance in all of its forms – from theatrical and site-specic performances to live and New Media art. e book is divided into two sections: • Concepts – key terms and ideas arranged according to the ve characteristic elements of performance art: time, space, action, performer, and audience. • Methodologies and turning points – the seminal theories and ways of reading performance, such as postmodernism, epic theatre, feminisms, happenings, and animal studies. Entries in both sections are accompanied by short case studies of specic performances and events, demonstrating creative examples of the ideas and issues in question. ree dierent introductory essays provide multiple entry points into the discussion of contemporary performance, and cross-references for each entry encourage the ploing of one’s own pathway. Reading Contemporary Performance is an invaluable guide, providing not just a strong grounding, but an exploration and contextualization of this broad and vital eld. Meiling Cheng is Associate Professor of Dramatic Arts/Critical Studies and English at the University of Southern California and Director of Critical Studies at USC School of Dramatic Arts, USA. Gabrielle H. Cody is Professor of Drama on the Mary Riepma Ross Chair at Vassar College., USA. -

19 Dispersion. Kunstpraktiken Und Ihre Vernetzungen

Olympe Bisher erschienen: Heft 1: Frauenrechte sind Menschenrechte (1/94) Heft 2: Wirtschaftspolitik – Konflikte um Definitionsmacht (2/95) Feministische Arbeitshefte zur Politik Heft 3: Sozialpolitik – Arena des Geschlechterkampfes (3/95) Heft 4: Wir leben hier – Frauen in der Fremde (4/95) Olympe 19/03 Heft 5: Der verwertete Körper – Selektiert. Reproduziert. Transplantiert. (5/96) Heft 6: Architektur – Der verplante Raum (6/96) Heft 7: Typisch atypisch – Frauenarbeit in der Deregulierung (7/97) Heft 8: 1848–1998: Frauen im Staat – Mehr Pflichten als Rechte (8/98) Heft 9: Einfluss nehmen auf Makroökonomie! (9/98) Heft 10: Gesundheit!!! Standortbestimmung in Forschung, Praxis, Politik (10/99) Heft 11: Feminismen und die Sozialdemokratie in Europa (11/99) Heft 12: Männer-Gewalt gegen Frauen (12/00) Heft 13: Marche Mondiale des femmes. Exploration – ein Mosaik (13/00) Heft 14: Nationalismus: Verführung und Katastrophe (14/01) Heft 15: Freiwilligenarbeit: wie frei – wie willig? (15/01) Heft 16: Ordnung muss sein! Pädagogische Inszenierungen (16/02) Heft 17: kreativ – skeptisch – innovativ, Frauen formen Recht (17/02) Heft 18: draussen – drinnen – dazwischen: Women of Black Heritage (18/03) Heft 19: Dispersion – Kunstpraktiken und ihre Vernetzungen (19/03) Heft 20: erscheint 2004 als Jubliäumsnummer zum Thema Provokation Dispersion Dispersion Kunstpraktiken und ihre Vernetzungen ISSN 1420-0392 ISBN 3-905087-42-1 Heft 19 Impressum Olympe. Feministische Arbeitshefte zur Politik Herausgeberinnen: Redaktion «Olympe» Heft Nr. 19/Dezember 2003: Dispersion – Kunstpraktiken und ihre Vernetzungen Auflage: 1000 ISSN 1420-0392 ISBN 3-905087-42-1 Redaktion: Jael Bueno (Ottenbach), Luisa Grünenfelder (Luzern), Verena Hillmann (Zürich), Elisabeth Joris (Zürich), Sabina Larcher (Winterthur), Mascha Madörin (Münchenstein), Sabina Schleuniger (Zürich), Michèle Spieler (Aarau), Silvia Staub-Bernasconi (Berlin, Zürich), Marina Widmer (St.Gallen), Susi Wiederkehr (Uster), Sandra Zrinski (Zürich). -

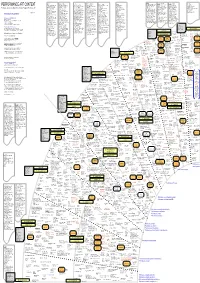

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

Abstract Suzanne Lacy

ABSTRACT SUZANNE LACY: THREE WEEKS IN MAY Suzanne Lacy’s continuous involvement in both the feminist and anti-rape movements during the 1970s helped raise social awareness on the subject of rape, an issue that was rarely taken seriously and often misunderstood. Beginning with a brief outline of the anti-rape movement and its feminist context, this paper will explore Lacy’s groundbreaking work, Three Weeks in May, a Los Angeles based event that addressed the issue of rape using a combination of art and social organization. This three week long event consisted of gallery installations, self- defense demonstrations, public speak-outs and street performances. In this thesis I will take into consideration the benefits of utilizing public art as a means to address social and political issues, and elucidate Three Weeks in May’s contribution to the anti-rape movement. Emily Louise Krause May 2010 SUZANNE LACY: THREE WEEKS IN MAY by Emily Louise Krause A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art in the College of Arts and Humanities California State University, Fresno May 2010 © 2010 Emily Louise Krause APPROVED For the Department of Art and Design: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Emily Louise Krause Thesis Author Keith Jordan (Chair) Art and Design Laura Meyer Art and Design Nancy Youdelman Art and Design For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS X I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship. -

OTIS Ben Maltz Gallery WB Exhibition Checklist 1 | Page of 58 (2012 Jan 23)

OTIS Ben Maltz Gallery WB Exhibition Checklist 1 | Page of 58 (2012_Jan_23) GUIDE TO THE EXHIBITION Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building October 1, 2011–January 28, 2012 Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design Introduction “Doin’ It in Public” documents a radical and fruitful period of art made by women at the Woman’s Building—a place described by Sondra Hale as “the first independent feminist cultural institution in the world.” The exhibition, two‐volume publication, website, video herstories, timeline, bibliography, performances, and educational programming offer accounts of the collaborations, performances, and courses conceived and conducted at the Woman’s Building (WB) and reflect on the nonprofit organization’s significant impact on the development of art and literature in Los Angeles between 1973 and 1991. The WB was founded in downtown Los Angeles in fall 1973 by artist Judy Chicago, art historian Arlene Raven, and designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville as a public center for women’s culture with art galleries, classrooms, workshops, performance spaces, bookstore, travel agency, and café. At the time, it was described in promotional materials as “a special place where women can learn, work, explore, develop their own point of view and share it with everyone. Women of every age, race, economic group, lifestyle and sexuality are welcome. Women are invited to express themselves freely both verbally and visually to other women and the whole community.” When we first conceived of “Doin’ It in Public,” we wanted to incorporate the principles of feminist art education into our process. -

Video Art at the Woman's Building

[From Site to Vision] the Woman’s Building in Contemporary Culture The [e]Book Edited by Sondra Hale and Terry Wolverton Stories from a Generation: Video Art at the Woman’s Building Cecilia Dougherty Introduction In 1994 Elayne Zalis, who was, at the time, the Video Archivist at the Long Beach Mu- seum of Art, brought a small selection of tapes to the University of California at Irvine for a presentation about early video by women. I was teaching video production at UC-Irvine at the time and had heard from a colleague that Long Beach housed a large collection of videotapes produced at the Los Angeles Woman’s Building. I mistakenly assumed that Zalis’s talk was based on this collection, and I wanted to see more. I telephoned her after the presentation. She explained that the tapes she presented were part of a then current exhibition called The First Generation: Women and Video, 1970-75, curated by JoAnn Hanley. She said that although the work from The First Generation was not from the Woman’s Building collection, the Long Beach Museum did in fact have some tapes I might want to see. Not only did they have the Woman’s Building tapes, but there were more than 350 of them. Moreover, I could visit the Annex at any time to look at them. I felt as if I had struck gold.1 Eventually I watched over fifty of the tapes, most of which are from the 1970s, and un- earthed a rich and phenomenal body of early feminist video work. -

The Ritual Body As Pedagogical Tool: the Performance Art of the Woman's

Anne Gauldin and Cheri Gaulke, The Malta Project , 1978. Performance at prehistoric temples in Malta. Photograph by Mario Damato. © Anne Gauldin and Cheri Gaulke. THE RITUAL BODY AS PEDAGOGICAL TOOL: THE PERFORMANCE ART OF THE WOMAN’S BUILDING Jennie Klein This essay is dedicated to the memory of Renee Edgington and Matt Francis. Prologue I would like to open this paper by recounting an experience that I had on the summer solstice of 1992, when I still lived in San Diego, the southernmost city in California. Because I had developed a local reputation as an art historian concerned with feminist issues, I was invited to a gathering of the Southern California chapter of the Women’s Caucus for Art for the occasion of the solstice. Although the invitation did say some - thing to the effect of a ritual dance, I couldn’t quite believe (or didn’t want to believe) that I was consciously entering into a part of feminism that I thought was best forgot - ten. Suffice it to say that I arrived at the gathering, which took place at a mountain adjacent to the east county home of one of the caucus members and found myself hiking up a mountain in order to take part in a “healing ritual.” After burning sage, invoking the spirits of the four compass points and participating in a “sacred” dance that the teacher had learned from an African dancer “with a really cute butt,” I hiked back down the mountain, eager to get away from a group of women who I believed were victims of a deluded consciousness. -

Oral History Interview with Rachel Rosenthal, 1989 September 2-3

Oral history interview with Rachel Rosenthal, 1989 September 2-3 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Rachel Rosenthal on September 2, 1989. The interview took place in Los Angeles, and was conducted by Moira Roth for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview [Tape 1, side A; 45-minute tape sides] MOIRA ROTH: This is a recording with Rachel Rosenthal in Los Angeles at her house, and it’s a recording for the Archives of American Art for the Oral History Program, September 2, 1989. If we could begin with your birth, where you were born, when, and a context. RACHEL ROSENTHAL: I was born in Paris in 1926, and my parents were both Russian Jews. My father was twenty years older than my mother. He was an emigré at age fourteen, which means that if he was born in 1874 he arrived in Paris in 1888, right? And went through “La Belle Epoque” [referring to Paris in the 1890s and turn of the century—RR] in Paris as a young man. He came penniless, and by the age of twenty-five he was a multi- millionaire. He had made a fortune in precious stones and Oriental pearls and became a wholesaler importer. The House, the business—was called Rosenthal et Frères, was himself and his brothers, and operated out of Paris; he sent his brothers all over the world to pick up these objects and bring them back to Paris where he prepared them for retail.