Museum of Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Cary Cordova 2005

Copyright by Cary Cordova 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Cary Cordova Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HEART OF THE MISSION: LATINO ART AND IDENTITY IN SAN FRANCISCO Committee: Steven D. Hoelscher, Co-Supervisor Shelley Fisher Fishkin, Co-Supervisor Janet Davis David Montejano Deborah Paredez Shirley Thompson THE HEART OF THE MISSION: LATINO ART AND IDENTITY IN SAN FRANCISCO by Cary Cordova, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2005 Dedication To my parents, Jennifer Feeley and Solomon Cordova, and to our beloved San Francisco family of “beatnik” and “avant-garde” friends, Nancy Eichler, Ed and Anna Everett, Ellen Kernigan, and José Ramón Lerma. Acknowledgements For as long as I can remember, my most meaningful encounters with history emerged from first-hand accounts – autobiographies, diaries, articles, oral histories, scratchy recordings, and scraps of paper. This dissertation is a product of my encounters with many people, who made history a constant presence in my life. I am grateful to an expansive community of people who have assisted me with this project. This dissertation would not have been possible without the many people who sat down with me for countless hours to record their oral histories: Cesar Ascarrunz, Francisco Camplis, Luis Cervantes, Susan Cervantes, Maruja Cid, Carlos Cordova, Daniel del Solar, Martha Estrella, Juan Fuentes, Rupert Garcia, Yolanda Garfias Woo, Amelia “Mia” Galaviz de Gonzalez, Juan Gonzales, José Ramón Lerma, Andres Lopez, Yolanda Lopez, Carlos Loarca, Alejandro Murguía, Michael Nolan, Patricia Rodriguez, Peter Rodriguez, Nina Serrano, and René Yañez. -

Muralism from the Museum to the Street ______

Muralism from the Museum to the Street ________________________________________ Course Number: VISST-300-16 Professor: Monica Bravo, PhD Class Meetings: Tuesdays 12-3 PM Email: [email protected] Classroom: Grad Center room 3 Office Hours: SF Library Tues. 11-12 and by appt. Course Description: Murals are typically large and often made for public consumption, whether displayed outside or indoors. Unlike many other forms of painting, a mural is literally part of a wall rather than created on a free-standing support such as a canvas or board. Site specificity is thus an essential part of a mural’s context. San Francisco is home to a number of important twentieth-century murals whose content is political and activist. This course will trace muralism’s history in San Francisco with an emphasis on Mexican, Chicanx, and women’s contributions. We will make several site visits to murals by Diego Rivera, Coit Tower, the Women’s Building, as well as contemporary graffiti in the Mission. This class encourages students to think big—either in terms of scale and/or social impact—about their own artmaking practices. Juana Alicia, La Llorona’s Sacred Waters, 2004. York and 24th Street, the Mission, SF. Learning Objectives: Upon completion of this course, students will be able to: • Identify various materials and techniques used to create murals, and understand their relatives benefits and drawbacks. • Apply the tools of formal analysis and critical visual thinking to murals, both familiar and unknown (visual literacy). • Critically evaluate textual analyses about murals in terms of their context, rhetoric, use of evidence, and interpretations. -

Arte Queer Chicano

bitácora arquitectura + número 34 EN Arte queer chicano Uriel Vides Bautista A mediados de 2015, la Galería de la Raza exhibió un mural que provocó triarcales de la sociedad dominante y los valores hegemónicos de la mascu- una acalorada discusión en redes sociales y actos de iconoclastia contem- linidad chicana, reafirmando a la vez el hecho de ser bilingües y biculturales poránea. El mural, que representa a sujetos queer, fue violentado tres veces dentro de Estados Unidos. consecutivas debido a cierta homofobia cultural que prevalece dentro de un sector de la comunidad chicana asentada en Mission District, San Fran- cisco. El contenido de esta obra y la significación dentro de su contexto son II algunos aspectos que analizaré a lo largo de este breve ensayo. El mural digital de Maricón Collective se inserta dentro de la tradición mu- ralista chicana, que tiene su origen en los murales que “los tres grandes”8 pintaron en distintos lugares de Estados Unidos, pero principalmente en I California. Mientras que en México el muralismo agotaba sus temáticas y La Galería de la Raza se encuentra ubicada en la 24th Street de Mission agonizaba junto con la vida de Siqueiros, en Estados Unidos resurgía de for- District, el barrio más antiguo de San Francisco.1 Este barrio fue en la década ma asombrosa gracias al Movimiento Chicano. Durante este periodo, según de 1970, en palabras del historiador Manuel G. Gonzales, “el corazón del George Vargas, los barrios chicanos de las principales ciudades del país se movimiento muralista de la ciudad”. La proliferación de murales fue impul- cubrieron de coloridos murales que, realizados de manera comunitaria, ex- sada, en este periodo, por los aires renovadores del llamado Movimiento presaban temas fundamentales para la comunidad como la raza, la clase, el Chicano.2 Ante la falta de espacios adecuados para la recreación y el espar- orgullo étnico y la denuncia social.9 cimiento, artistas y activistas chicanos pugnaron por la creación de centros En un ensayo, Edward J. -

CALIFAS El Arte De La Zona Fronteriza México-Estados Unidos

CALIFAS El Arte de la Zona Fronteriza México-Estados Unidos Art of the US-Mexico Borderlands CALIFAS El Arte de la Zona Fronteriza México-Estados Unidos Art of the US-Mexico Borderlands AGENCY (Ersela Kripa & Stephen Mueller) Chester Arnold Jesus Barraza Enrique Chagoya CRO studio (Adriana Cuellar & Marcel Sánchez) Ana Teresa Fernández Nathan Friedman Guillermo Galindo Curated by Michael Dear and Ronald Rael Rebeca García-González Assisted by Denise Klarquist Andrea Carrillo Iglesias Amalia Mesa-Bains September 11 - November 16, 2018 Richard Misrach Richmond Art Center Alejandro Luperca Morales Julio César Morales Postcommodity Rael San Fratello (Ronald Rael & Virginia San Fratello) Fernando Reyes Favianna Rodriguez Stephanie Syjuco David Taylor Judi Werthein Rio Yañez © 2018 Richmond Art Center All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the Richmond Art Center. This exhibition and catalogue were organized by the Richmond Art Center and supported, in part, by the Zellerbach Family Foundation; Susan Chamberlin, Matt and Margaret Jacobson; and anonymous donors. Image Credits front cover: Julio César Morales, Day Dreaming Series (detail), 2018. Courtesy of the Artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco pp. 6-7: Photograph by Michael Dear. Collage by Michelle Shofet pp. 12-13: LINEA DIVISORIA ENTRE MEXICO Y LOS ESTADOS UNIDOS, Colección Límites México-EEUU, Carpeta No. 4, Lámina No. 54; Autor: Salazar Ilárregui, José, Año 1853. Mapoteca ‘Manuel Orozco y Berra’, Servicio de Información Estadistica Agroalimentaria y Pesquera, SARGAPA. Reproduced with permission. Digital restoration by Tyson Gaskill pp. 23, 28, 36-37, 46-47: Photographs by Michael Dear back cover: Andrea Carrillo Iglesias, La Reina Califia / Queen Califia, 2018. -

Latino San Francisco Put Together for You by the Latino Public Radio Consortium

Guide to San Francisco LatinoJune 2011 Guillermo Gómez Peña, performance artist Latino Public Radio Consortium P.O. Box 8862 Denver, CO 80201-8862 303-877-4251 [email protected] www.lationopublicradioconsortium.org Latino Public Radio programming public radio OAKLAND/www.radiobilingue.org National News BERKELEY La Raza Chronicles, Con Sabor, Ritmo de las Américas, Rock en Rebelión, La Onda Bajita, Musical Colors, Radio 20 50 SAN FRANCISCO Pájaro Latino Americano, La Verdad Musical, Andanzas Welcome to the Guide to Latino San Francisco put together for you by the Latino Public Radio Consortium. Just like Latino public broadcasting, the Latino culture of a city is often ignored by traditional tourist magazines and guides. In a city known by the Spanish name for Saint Francis, you know there’s definitely a Latino influence at work. We’re here to assure you that there is more to San Francisco than Fisherman’s Wharf, cable cars and sourdough bread. There are pupusas, tortillas, Día de los Muertos kitsch, traditional Mexican folk art and edgy, contemporary expressions of what it’s like to be Latino in one of America’s major cities. Maybe it’s the salt air that produces such creativity, talent, skill and can-do attitude among Latinos in this city by the bay. Just scratching the surface, we found an abundance of Latino food, art, music, dancing, literature and activities that you’rewelcome sure to enjoy while in San Francisco. Special thanks to the contributors Adriana Abarca, Ginny Z. Berson, Linda González, Chelis López, Luis Medina, Samuel Orozco, Manuel Ramos, Nina Serrano. -

20181017 Consent Calendar 1-3

Mural Design Information Form LEAD ARTIST ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE EMAIL PHONE PROJECT COORDINATOR ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE EMAIL PHONE SPONSORING ORGANIZATION ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE EMAIL PHONE FUNDING SOURCES PROPOSED SITE (address, cross street ) DISTRICT District numbers can be found at http://sfgov.org/elections/district-citywide-maps MURAL TITLE DIMENSIONS ESTIMATED SCHEDULE (start and completion dates) 1. Proposal (describe proposed design, site and theme. Attach a separate document if needed). 2. Materials and processes to be used for wall preparation, mural creation and anti-graffiti treatment. 3. List individuals and groups involved in the mural design, preparation and implementation. Attach the following documents to this form: 1. Lead artist's resume/qualifications and examples of previous work 2. Three (3) letters of community support 3. Letter or resolution approving proposal from city department or; 4. Letter of approval from private property owner along with Property Owner Authorization Form 5. Signed Artist Waiver of Property Rights for artwork placed upon city property or; 6. Signed Artist Waiver of Proprietary Rights financed in whole or in part by city funds for artwork placed upon private property 7. Maintenance Plan (including parties responsible for maintenance) 8. Color image of design 9. One image of the proposed site and indicate mural dimensions YUKA EZOE www.YukakoEzoe.com SAN FRANCISCO, CA EDUCATION 2005 Garret Rietveld Academy of Arts, Amsterdam, Netherlands (spring session) 2006 BFA in Interdisciplinary Art, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA 2008 Women’s Initiative, San Francisco, CA, a small business development NPO PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Precita Eyes Muralists Association, Inc. -

ART on the WALLS ARTISTS RIGHTS of INTEGRITY & ATTRIBUTION in MURALS & SCULPTURES Brooke Oliver, Attorney Brooke Oliver Law Group, P.C

ART ON THE WALLS ARTISTS RIGHTS OF INTEGRITY & ATTRIBUTION IN MURALS & SCULPTURES Brooke Oliver, Attorney Brooke Oliver Law Group, P.C. 50 Balmy Alley San Francisco, CA 94110 415/641-1116 www.artemama.com BIO: BROOKE OLIVER represents artists, activists, and entrepreneurs. She founded Brooke Oliver Law Group, P.C., an art, entertainment and business law firm. She has been called a “folk hero of copyright law” for her work in protecting muralists and activists’ intellectual property and murals. Her business practice helps creative entrepreneurs establish and grow companies and protect their intellectual property. The firm’s litigation practice emphasizes copyright and trademark. Clients include the Jerry Garcia Estate LLC, artists Michael Parkes, Eyvind Earle, Judy Baca, and Juana Alicia, and photographers on behalf of Corbis. She is intellectual property counsel for Dolores Huerta, the Cesar E. Chavez Foundation, the United Farm Workers Union/A.F.L.-C.I.O, the Mexican Museum, Swell Cinema, and many graphic designers, photographers, and filmmakers. She is general counsel for San Francisco Pride Celebration, and the San Francisco World Music Festival. Business clients include Rocket Science, Chi Living, Toys in Babeland, Fattoush and La Posta restaurants, EcoRep, Pyramind, Mayacama Golf Club, Varnish Fine Art Gallery, and Herter Studio. CAUTIONARY NOTE: This article is for research and reference purposes only. It does not constitute and should not be considered to be legal advice. Every effort has been made to assure its accuracy as of the date it was written, but the law constantly evolves and changes. Artists and others with a specific legal question or problem should retain a knowledgeable attorney to advise them. -

Yolanda M. Lopez Papers CEMA 11

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf109nb0nx No online items Guide to the Yolanda M. Lopez Papers CEMA 11 Finding aid prepared by Project archivist: Salvador Güereña; principal processors: Todd Chatman; student assistants: Aneesa Motala; machine-readable finding aid created by Alexander Hauschild UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Email: [email protected]; URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections © 1999 Guide to the Yolanda M. Lopez CEMA 11 1 Papers CEMA 11 Title: Yolanda M. Lopez papers Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 11 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 8.5 linear feet(19 boxes: 18 document boxes, 1 oversize portfolio box and posters) Date (bulk): Bulk, 1961-1998 Date (inclusive): 1961-2007 General Physical Description note: 1.5 linear feet (3 hollinger boxes, 1 oversize portfolio box, 1 flat file portfolio box of silkscreen prints) Shelf location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the library's online catalog. creator: Lopez, Yolanda M., 1942- Biography Yolanda Lopez was born in San Diego, California in 1942. As the eldest daughter of three, she was raised by her mother and her mother's parents in the Logan Heights neighborhood. After graduating high school, Lopez moved to the San Francisco Bay Area and in 1968 became part of the San Francisco State University Third World Strike. She also worked as a community artist in the Mission District with a group called Los Siete de la Raza. -

Brava with Calle 24 & Precita Eyes Muralists Present

Brava with Calle 24 & Precita Eyes Muralists present the 6th Annual Baile en la Calle: The Mural Dances Sunday, May 6, 2018 FREE Tours begin at 11am, 12pm, 1pm, 2pm Brava @ 2781 24th Street Brava! for Women in the Arts’ annual event takes over the streets and alleys of San Francisco’s Mission District to celebrate and preserve its living cultural heritage! Now in its sixth year, Baile en la Calle: The Mural Dances invites the Bay Area’s most dynamic dance companies and performing artists to interpret the murals through music and dance, alongside detailed narration by docents from Precita Eyes Muralists. Baile en la Calle: The Mural Dances provides audiences an intricate look at each mural and its relationship to the culture and the life of the Mission. This year’s tour includes a new mural by the artist Agana commissioned by Brava to celebrate the opening of our long-awaited storefront spaces, along with “Take it From the Top: Latin Rock” which covers an entire house, Juana Alicia's 2004 "La Llorona’s Sacred Waters," Swoon's untitled 2016 wheat-paste mural, and a few surprises! PEFORMERS Duniya Dance & Drum Company Vanessa Sanchez and La Mezcla Mariachi Juvenil La Misión Cuicacalli Dance Company Leticia Hernandez Loco Bloco Duniya Dance & Drum Company Formed in April 2007, Duniya Dance & Drum Company creates dance and music from Punjab, India, and Guinea, West Africa, as well as unique blends of these forms and beyond. The word duniya means “world” in a wide array of languages, including Punjabi, Arabic, Susu and Wolof. -

ON AIR, ONLINE, on the GO JANUARY 2018 | MEMBER GUIDE ADVERTISEMENTS from the President Where to Tune In

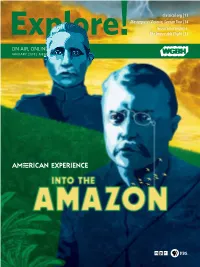

Classical.org | 13 Masterpiece/Victoria, Season Two | 14 Nova/Solar Impulse: The Impossible Flight | 21 ON AIR, ONLINE, ON THE GO JANUARY 2018 | MEMBER GUIDE ADVERTISEMENTS From the President Where to Tune in In with the New! TV We begin the new year in a spirit of exploration and adventure as we head into a new season of programming at WGBH. This month, WGBH brings you a host of inspiring, Digital broadcast FiOS RCN Cox Charter (Canada) Bell ExpressVu entertaining and educational premieres from Masterpiece, American Comcast Experience, Nova, Antiques Roadshow and more! WGBH 2 2.1 2 2 2 2 2 284 American Experience’s Into the Amazon (pg. 12) tells the remarkable WGBH 2 HD 2.1 802 502 602 1002 782 819 story of the 1914 journey taken by President Theodore Roosevelt (left) and WGBX 44 44.1 16 44 14 804 21 n/a Brazilian explorer Candido Rondon into the heart of the South American rainforest. With a crew of more than WGBX 44 HD 44.1 801 544 n/a n/a n/a n/a 140 Brazilians, Roosevelt and Rondon World 2.2 956 473 94 807 181 n/a set out to explore an uncharted Create 44.3 959 474 95 805 182 n/a Amazon tributary, along the way WGBH Kids 44.4 958 472 93 n/a 180 n/a battling the unforgiving landscape, Boston Kids & n/a 22 n/a 3 n/a n/a n/a disease and countless other dangers. Family (Boston only) “Like all great journeys, the story Channel numbers and availability may vary by community. -

BANCROFTIANA Number 144 • University of California, Berkeley • Spring 2014

Newsletter of The Friends of The Bancroft Library BANCROFTIANA Number 144 • University of California, Berkeley • Spring 2014 THE ORIGINALS Pioneering African-American Faculty and Staff Reveal Stories of Struggle and Triumph avid Blackwell remembered the first time he was Some, like Blackwell, who died in 2010, were lead- Dapproached about a job teaching math on the UC ing scholars of fields including mathematics, engineering, Berkeley faculty. The year was 1942, and Blackwell, an and social welfare. Some headed academic departments African-American researcher then spending a year on fel- including dramatic arts and art practice, and served as lowship at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, was groundbreaking senior campus administrators. And some interviewed by a visiting Berkeley professor, Jerzy Neyman. played important roles in numerous transformative events, Blackwell remembered that the interview went well, but particularly during the 1960s and 1970s, including the that a couple of months later Neyman phoned to tell him Third World College Strike in 1969, a nearly two-month that the department had decided to hire a woman instead. campaign by four ethnic student groups and their allies “So that was fine,” Blackwell recalled. “I hadn’t that transformed education at the university. thought there was any possibility I would get the position, The action eventually led to the formation of the anyway. Berkeley was an absolutely first-class university, African-American studies department and other curricular and I was just a fresh young Ph.D. and so that was that.” diversity initiatives with national repercussions includ- It wasn’t until 10 years later, when Blackwell was hired ing the ethnic studies and women’s studies majors and the as one of the first black professors at Berkeley, that he Continued on page 6 heard the real story of what happened to his earlier application from several members of the math depart- ment. -

Andrew Kong Knight [email protected] Andrewkongknight.Com 925-413-1975

Andrew Kong Knight [email protected] andrewkongknight.com 925-413-1975 Objective: College drawing and painting instructor position in a positive, collaborative environment that utilizes my experience as a highly effective, award-winning artist, educator, and community arts leader Summary ● Master of Fine Arts – John F. Kennedy University (JFKU), Berkeley, CA ● Bachelor of Fine Arts – San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), San Francisco, CA ● Single-subject Teacher Credential in Art with Cross-cultural Language and Academic Development Language (CLAD) emphasis ● Over thirty years of fine art and commercial art experience ● Over twenty years art teaching and lecturing experience ● Winner of twenty local and national art and education awards ● Students have won dozens of regional and national art awards and scholarships ● Proven success promoting and exhibiting students’ work locally, nationally, and in various newspapers, online media, radio, and television stations Art Teaching ● Teaching and lecturing experience in university, college, and high school art classes for over twenty years ● Presented dozens of lectures to universities, colleges, high schools, and art groups throughout the San Francisco Bay Area ● Supervised several university, college, and K-12 mural art projects ● Successfully facilitated the exhibition of students’ work locally and nationally ● Promoted dozens of student art projects to San Francisco Bay Area media, resulting in more than twenty news articles in major metropolitan newspapers, as well as local television coverage Art Career Highlights ● Fine art featured in numerous local, national, and world-wide publications ● Exhibit fine art in museums, galleries, and art spaces throughout the country ● Artwork commissioned by companies and publishers nationally and internationally ● Completed forty monumental public art mural commissions while mentoring college and university students in the process 1 Education & Certification John F.