Supplementary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

As Time Passes Over the Land

s Time Passes over theLand A White Mountain Art As Time Passes over the Land is published on the occasion of the exhibition As Time Passes over the Land presented at the Karl Drerup Art Gallery, Plymouth State University, Plymouth, NH February 8–April 11, 2011 This exhibition showcases the multifaceted nature of exhibitions and collections featured in the new Museum of the White Mountains, opening at Plymouth State University in 2012 The Museum of the White Mountains will preserve and promote the unique history, culture, and environmental legacy of the region, as well as provide unique collections-based, archival, and digital learning resources serving researchers, students, and the public. Project Director: Catherine S. Amidon Curator: Marcia Schmidt Blaine Text by Marcia Schmidt Blaine and Mark Green Edited by Jennifer Philion and Rebecca Chappell Designed by Sandra Coe Photography by John Hession Printed and bound by Penmor Lithographers Front cover The Crawford Valley from Mount Willard, 1877 Frank Henry Shapleigh Oil on canvas, 21 x 36 inches From the collection of P. Andrews and Linda H. McLane © 2011 Mount Washington from Intervale, North Conway, First Snow, 1851 Willhelm Heine Oil on canvas, 6 x 12 inches Private collection Haying in the Pemigewasset Valley, undated Samuel W. Griggs Oil on canvas, 18 x 30 inches Private collection Plymouth State University is proud to present As Time Passes over the about rural villages and urban perceptions, about stories and historical Land, an exhibit that celebrates New Hampshire’s splendid heritage of events that shaped the region, about environmental change—As Time White Mountain School of painting. -

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

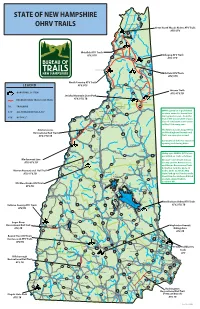

State of New Hampshire Ohrv Trails

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Third Connecticut Lake 3 OHRV TRAILS Second Connecticut Lake First Connecticut Lake Great North Woods Riders ATV Trails ATV, UTV 3 Pittsburg Lake Francis 145 Metallak ATV Trails Colebrook ATV, UTV Dixville Notch Umbagog ATV Trails 3 ATV, UTV 26 16 ErrolLake Umbagog N. Stratford 26 Millsfield ATV Trails 16 ATV, UTV North Country ATV Trails LEGEND ATV, UTV Stark 110 Groveton Milan Success Trails OHRV TRAIL SYSTEM 110 ATV, UTV, TB Jericho Mountain State Park ATV, UTV, TB RECREATIONAL TRAIL / LINK TRAIL Lancaster Berlin TB: TRAILBIKE 3 Jefferson 16 302 Gorham 116 OHRV operation is prohibited ATV: ALL TERRAIN VEHICLE, 50” 135 Whitefield on state-owned or leased land 2 115 during mud season - from the UTV: UP TO 62” Littleton end of the snowmobile season 135 Carroll Bethleham (loss of consistent snow cover) Mt. Washington Bretton Woods to May 23rd every year. 93 Twin Mountain Franconia 3 Ammonoosuc The Ammonoosuc, Sugar River, Recreational Rail Trail 302 16 and Rockingham Recreational 10 302 116 Jackson Trails are open year-round. ATV, UTV, TB Woodsville Franconia Crawford Notch Notch Contact local clubs for seasonal opening and closing dates. Bartlett 112 North Haverhill Lincoln North Woodstock Conway Utility style OHRV’s (UTV’s) are 10 112 302 permitted on trails as follows: 118 Conway Waterville Valley Blackmount Line On state-owned trails in Coos 16 ATV, UTV, TB Warren County and the Ammonoosuc 49 Eaton Orford Madison and Warren Recreational Trails in Grafton Counties up to 62 Wentworth Tamworth Warren Recreational Rail Trail 153 inches wide. In Jericho Mtn Campton ATV, UTV, TB State Park up to 65 inches wide. -

N.H. State Parks

New Hampshire State Parks WELCOME TO NEW HAMPSHIRE Amenities at a Glance Third Connecticut Lake * Restrooms ** Pets Biking Launch Boat Boating Camping Fishing Hiking Picnicking Swimming Use Winter Deer Mtn. 5 Campground Great North Woods Region N K I H I A E J L M I 3 D e e r M t n . 1 Androscoggin Wayside U U U U Second Connecticut Lake 2 Beaver Brook Falls Wayside U U U U STATE PARKS Connecticut Lakes Headwaters 3 Coleman State Park U U U W U U U U U 4 Working Forest 4 Connecticut Lakes Headwaters Working Forest U U U W U U U U U Escape from the hectic pace of everyday living and enjoy one of First Connecticut Lake Great North Woods 5 Deer Mountain Campground U U U W U U U U U New Hampshire’s State Park properties. Just think: Wherever Riders 3 6 Dixville Notch State Park U U U U you are in New Hampshire, you’re probably no more than an hour Pittsbur g 9 Lake Francis 7 Forest Lake State Park U W U U U U from a New Hampshire State Park property. Our state parks, State Park 8 U W U U U U U U U U U Lake Francis Jericho Mountain State Park historic sites, trails, and waysides are found in a variety of settings, 9 Lake Francis State Park U U U U U U U U U U ranging from the white sand and surf of the Seacoast to the cool 145 10 Milan Hill State Park U U U U U U lakes and ponds inland and the inviting mountains scattered all 11 Mollidgewock State Park U W W W U U U 2 Beaver Brook Falls Wayside over the state. -

New Hampshire Granite State Ambassadors

New Hampshire Granite State Ambassadors www.NHGraniteStateAmbassadors.org Regional Resource & Referral Guide: Western White Mountains Region Use this document filled with local referrals from Granite State Ambassadors & State Welcome Center attendants as an informational starting point for guest referrals. For business referrals, please reference your local brochures & guides. Hidden Gems: ● Pollyanna Statue, 92 Main Street, Littleton – Tribute to hometown author Eleanor H. Porter, creator of the optimistic Character Pollyanna. Official Pollyanna Glad Day held in June. (http://www.golittleton.com/pollyanna.php) ● The Rocks, Bethlehem – The Rocks is the North Country Conservation & Education Center for the Society for the Protection of NH Forests. NH Christmas tree farm, and much more including family friendly hikes year-round, maple-sugaring in Spring and picnic area in the formal gardens. Great views. (https://therocks.org/) ● Wren Arts Community, 2011 Main St., Bethlehem – Women’s Rural Entrepreneurial Network; gallery serves as a cultural outlet for creative expression; new shows monthly highlighting the work of local and regional artists in a variety of mediums. (http://wrenworks.org/gallery/) Curiosity: ● Redstone Rocket, Town Common, Warren (just off NH 25) – The only town that has its own Redstone Missile, which is a remnant the Cold War. Small kiosk has Missile Information and the Warren Historical Museum is nearby. Moved to Warren in 1971 from the U. S. Army’s Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville Alabama. (http://www.moosescoopsicecream.com/warren--nh-s-redstone-missile.html) Covered Bridges: ● Smith Millennium Bridge, Smith Bridge Rd., Plymouth – ½ mile north of NH 25. ● Blair Bridge, Campton – east of US 3, 2 miles north of Livermore Falls. -

Winter Tours to an Extreme World Legendary Mt

DIRECTIONS, INFORMATION Drive, Tour & Explore the AMERICA'S FIRST & OLDEST Winter Tours to an Extreme World Legendary Mt. Washington Auto Road WELCOME TO THE & OTHER WHITE MOUNTAIN MT. WASHINGTON AUTO ROAD MAN-MADE ATTRACTION ATTRACTIONS The Mt. Washington Auto Please note that we are Road is located on Route sometimes hard to find with MT. WASHINGTON 6,288’ 16 in Pinkham Notch, GPS devices. Try “1 Mount NH, 18 miles 3.875north of Washington Auto Road, 4 4 3.875 3.75 NE Alpine Garden • 7-mile post North Conway, NH and 8 Gorham, NH” or simply Tuckerman miles south of the town of enter “Mt WashingtonBRUNSWICK Auto Ravine Gorham, NH. Road” or “Glen House” in Huntington Saint Ravine • 6-mile post A Great Gulf your GPS. John NOVA SCOTIAHalifax Wilderness D As the highest peak Cragway QUEBEC A in the Northeast, • 5-mile post N Chandler Ridge A Mt. Washington offers Montreal C MAINE spectacular panoramic Mt. Washington SnowCoach “Top-of-the-Tour” 4,200 feet views and is known as 4-mile post • home to the world’s (weather permitting) The Horn VT Portland worst weather! Halfway 93 16 House Site NH93 REACH THE HIGHEST PEAK IN THE NORTHEAST! Mt. Washington Auto Road• 3-mile post CANADA 95 Boston Appalachian Albany MA Trail Crossing Low’s Bald NEW 90 WHITE MOUNTAIN • 2-mile post Spot - 2875’ YORK NATIONAL FOREST 88 14 JEFFERSON The Mt. Washington White Mountains Attractions 3 95 2 GORHAM Auto Road offers easy 1 Alpine Adventures 115 2 Attitash Mountain Resort 93 11 access to 4 unique alpine 3 Cannon Aerial Tramwa84y PINKHAM NOTCH FRANCONIA 12 4 Clark’s Trading Post BRETTON 17 zones and is home to © Copyright 2015 - Mt Washington Auto Road Auto Washington 2015 - Mt © Copyright 5 Conway Scenic Railroad 3 WOODS S FRANCONIA NOTCH • 1-mile post rare alpine flowers and 6 Cranmore Mountain Resort New York 15 7 302 7 Flume Gorge 50 MILE 80 GLEN bird species. -

White Mountain National Forest Alternative Transportation Study

White Mountain National Forest Alternative Transportation Study June 2011 USDA Forest Service White Mountain National Forest Appalachian Mountain Club Plymouth State University Center for Rural Partnerships U.S. Department of Transportation, John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 09/22/2011 Study September 2009 - December 2011 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER White Mountain National Forest Alternative Transportation Study 09-IA-11092200-037 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Alex Linthicum, Charlotte Burger, Larry Garland, Benoni Amsden, Jacob 51VXG70000 Ormes, William Dauer, Ken Kimball, Ben Rasmussen, Thaddeus 5e. TASK NUMBER Guldbrandsen JMC39 5f. -

Phase Ia Archaeological Survey Granite Reliable Power, Llc Proposed Windpark

PHASE IA ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY GRANITE RELIABLE POWER, LLC PROPOSED WINDPARK COOS COUNTY NEW HAMPSHIRE Prepared by: THE Louis Berger Group, INC. 20 Corporate Woods Blvd. Albany, New York 12211 Prepared for: Granite Reliable Power, LLC a subsidiary of Noble Environmental Power, LLC 8 Railroad Avenue April 2008 Essex, Connecticut 06426 Phase IA Archaeological Survey Granite Reliable Power, LLC, Proposed Windpark Coos County, New Hampshire Abstract On behalf of Granite Reliable Power, LLC, a subsidiary of Noble Environmental Power, LLC, of Essex, Connecticut, The Louis Berger Group, Inc. (Berger), has completed a Phase IA archaeological investigation for the proposed Granite Reliable Power Windpark (Windpark), Coos County, New Hampshire. The purpose of the survey was to identify and assess areas of archaeological sensitivity (or potential) and identify any archaeological sites within the area of potential effects (APE), which for this survey includes all parts of the proposed Windpark that will be subject to ground disturbance, including turbine construction, access road improvements and construction, collection line installation, and switchyard and substation construction. This investigation was designed in accordance with guidelines issued by the New Hampshire Department of Historical Resources (NHDHR). The Windpark is proposed for installation on private land in the central portion of Coos County, encompassing a total area of approximately 80,000 acres, of which the APE is a subset. The Windpark is located in a current logging area in the White Mountains region of north-central New Hampshire. The northern extent of the wind turbine locations within the APE includes the upper reaches of Dixville Peak. Moving south, the wind turbine area includes the named summits of Mt. -

The White-Mountain Village of Bethlehem As a Resort for Health

AS A THE White-Mountain Village OF BETHLEHEM AS A Resort for Health and Pleasure. BOSTON: PRINTED BY RAND, AVERY, & CO. 1880. INTRODUCTORY. In preparing the following pages the editor has en- deavored to present in a convenient form such information as experience has shown to be of use to the tourist and health-seeker. Eschewing all high-flown language, he has confined himself to a plain description of the town and its surround- ings. Such a work is necessarily more or less of a compi- lation, and the editor frankly acknowledges his indebted- ness to Osgood’s “ White Mountains” and to Mrs. E. K. Churchill’s pleasant little work on Bethlehem. To “ The White-Mountain Echo,” and its accomplished editor, Mr. Markenfield Addey, he also is under obligations for almost the whole of the chapter on railroads, steamer, and other methods of approach to Bethlehem. The chapter on climate is a reprint of Dr. W. II. Gedding’s article which appeared last summer in “ The Boston Med- ical and Surgical Journal,” with corrections and addi- tions, the more extended experience of the writer having enabled him to add much that is new and interesting. Although originally written for a medical journal, it is sufficiently free from technical expressions to be perfectly intelligible to the general reader. I. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF BETHLEHEM, ITS HOTELS, BOARDING-HOUSES, ETC. Located in the midst of a section of country abound- ing in natural beauties, the little village of Bethlehem presents a combination of attractions rarely met with at our summer-resorts. There -

Guide to Crawford Notch State Park

Guide to Crawford Notch State Park On US Route 302 Harts Location, NH (12 miles NW of Bartlett) This 5,775 acre park provides access to numerous hiking trails, waterfalls, fishing, wildlife viewing, and spectacular mountain views. Crawford Notch State Park is rich in history with the famous Willey House. There are picnicking areas, parking for hiking, as well as scenic pull-offs and a visitor information center. Park History Discovery: In 1771 a Lancaster hunter, Timothy Nash, discovered what is now called Crawford Notch, while tracking a moose over Cherry Mountain. He noticed a gap in the distant mountains to the south and realized it was probably the route through the mountains mentioned in Native American lore. Packed with provisions, he worked his way through the notch and on to Portsmouth to tell Governor John Wentworth of his discovery. Doubtful a road could be built through the mountains, the governor made him a deal. If Nash could get a horse through from Lancaster he would grant him a large parcel of land at the head of the notch, with the condition he build a road to it from the east. Nash and his friend Benjamin Sawyer managed to trek through the notch with a very mellow farm horse, that at times, they were required to lower over boulders with ropes. The deal with the governor was kept and the road, at first not much more than a trail, was opened in 1775. Settlement: The Crawford family, the first permanent settlers in the area, exerted such a great influence on the development of the notch that the Great Notch came to be called Crawford Notch. -

May 23, 2013 Free

VOLUME 37, NUMBER 28 MAY 23, 2013 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY Valley Feature Catch ‘m All Local woodworker Fiddleheads, fish, crafts playsets and “the willies” without peer Page 2 Page 22 A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH Valley Feature Workbench: Cedar Swings and Playsets locomote through the Valley and New England, handcrafted by Pete Lawson By Rachael Brown When the housing market soured, and the Chinese had a screw up, Pete Lawson's lum- ber business just may have be- come sweeter. You see, Lawson, a Colby College graduate and New England native, has been in the lumber commodities and wholesale business since 1976. Lawson sold to the housing and swing and playset indus- try, with cedar being his wood of choice, earning him the nickname of Cedar Pete and a reputation for quality crafted swing and playsets made right here in the USA. As a matter Rachael Brown Courtesy of fact, right here in Glen. Pete Lawson of Cedar Swings and Playsets, uses his space so efficiently Cedar Swing and Playset's Chocorua model with added options, lower Lawson tells his story. he is able produce cedar playsets like the big companies in a small space. deck playhouse package and a firehouse pole. Lawson's most popular “There was a point in time "It doesn't take a giant factory." model hand crafted in Glen. when people started using less cedar, started using com- “In this business, it is impos- the Valley pops up. I can ab- Lawson continues to explain me the most nervous, setting posite decking, vinyl siding.