Mountains Oceans Giants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Phytopoetics: Upending the Passive Paradigm with Vegetal Violence and Eroticism Joela Jacobs University of Arizona [email protected] Abstract This article develops the notion of phytopoetics, which describes the role of plant agency in literary creations and the cultural imaginary. In order to show how plants prompt poetic productions, the article engages with narratives by modernist German authors Oskar Panizza, Hanns Heinz Ewers, and Alfred Döblin that feature vegetal eroticism and violence. By close reading these texts and their contexts, the article maps the role of plant agency in the co-constitution of a cultural imaginary of the vegetal that results in literary works as well as societal consequences. In this article, I propose the notion of phytopoetics (phyto = relating to or derived from plants, and poiesis = creative production or making), parallel to the concept of zoopoetics.1 Just as zoopoetics describes the role of animals in the creation of texts and language, phytopoetics entails both a poetic engagement with plants in literature and moments in which plants take on literary or cultural agency themselves (see Moe’s [2014] emphasis on agency in zoopoetics, and Marder, 2018). In this understanding, phytopoetics encompasses instances in which plants participate in the production of texts as “material-semiotic nodes or knots” (Haraway, 2008, p. 4) that are neither just metaphor, nor just plant (see Driscoll & Hoffmann, 2018, p. 4 and pp. 6-7). Such phytopoetic effects manifest in the cultural imagination more broadly.2 While most phytopoetic texts are literary, plant behavior has also prompted other kinds of writing, such as scientific or legal Joela Jacobs (2019). -

Alfred Döblins Weg

210 -- Sabine Schneider Rutsch, Bettina: Leiblichkeit der Sprache. Sprachlichkeit des Leibes. Wort, Gebärde, Tanz bei Alexander Honold Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Frankfurt a. M. 1998. Schlötterer, Reinhold: ,,Elektras Tanz in der Tragödie Hugo von Hofmannsthals". In: Exotischentgrenzte Kriegslandschaften: Hofmannsthal-Blätter 33 (1986), 5. 47-58. Schneider, Florian: ,,Augenangst? Die Psychoanalyse als ikonoklastische Poetologie". In: Alfred DöblinsWeg zum „Geonarrativ" Hofmannstha/-Jahrbuch 11 (2001), 5. 197- 240. Schneider, Sabine: ,,Das Leuchten der Bilder in der Sprache. Hofmannsthals medienbewusste Berge Meere und Giganten Poetik der Evidenz". In: Hofmannsthal-Jahrbuch 11 (2003), 5. 209-248. Schneider, Sabine: ,,Die Welt der Bezüge. Hofmannsthal zur Autorität des Dichters in seiner Was eigentlich geschieht an den Rändern der durch Atmosphäre, Gravitation und Zeit". In: Colloquium Helveticum 41 (2010), 5. 203-221. Drehbewegung verbundenen Heimatkugel irdischen Lebens? Etwa dann, wenn die Schneider, Sabine: ,,Helldunkel - Elektras Schattenbilder oder die Grenzen der semiotischen zivilisatorischen Makro-Ereignisse von diesem Erdklumpen nicht mehr zusam- Utopie". In: dies.: Verheißung der Bilder. Das andere Medium in der Literatur um 1900. mengehalten werden können? Tübingen 2006, 5. 342- 368. Schneider, Sabine: .,Poetik der Illumination. Hugo von Hofmannsthals Bildreflexionen im Kein Ohr hörte das Schlürfen Schleifen, das seidig volle Wehen an dem fernen Saum. Ge- Gespräch über Gedichte". In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 71 (2008), Heft 3, schüttelt wurde die Luft im Rollen und Stürzen der Kugel, die sie mitschleppte. Lag gedreht an 5. 389-404. der Erde, schmiegte sich gedrückt an dem rasenden Körper an, wehte hinter ihm wie ein Seel, Martin: Die Macht des Erscheinens. Textezur Ästhetik. Frankfurt a. M. 2007. aufgelöster Zopf. (BMG 367)1 Sommer, Manfred: Evidenz im Augenblick. -

Chronik ALFRED DÖBLIN 1878

Leben & Werk - Chronik ALFRED DÖBLIN 1878 - 1957 10. August 1878: Geburt Alfred Döblins in Stettin als viertes und vorletztes Kind jüdischer Eltern, des Schneidermeisters Max Döblin (1846-1921) und seiner Frau Sophie, geb. Freudenheim (1844-1920). 1888: Döblins Vater verlässt Frau und Kinder; die Mutter zieht mit ihren fünf Kindern nach Berlin. 1891-1900: Besuch des Köllnischen Gymnasiums in Berlin. Ausbildung literarischer, philosophischer und musikalischer Neigungen. Lektüre Kleists, Hölderlins, Dostojewskijs, Schopenhauers, Spinozas, Nietzsches. Entstehung erster literarischer und essaysistischer Texte, darunter Alfred Döblin. Kinderfoto um Modern. Ein Bild aus der Gegenwart (1896). 1888 1900: Niederschrift des ersten Romans Jagende Rosse (zu Lebzeiten unveröffentlicht). 1900-1905: Medizinstudium in Berlin und Freiburg i.Br. Beginn der Freundschaft mit Herwarth Walden und Else Lasker-Schüler. Entstehung des zweiten Romans Worte und Zufälle (1902/03; als Buch 1919 unter dem Titel Der schwarze Vorhang veröffentlicht), zweier kritischer Nietzsche Essays (1902/03) und mehrerer Erzählungen, darunter Die Ermordung einer Butterblume. 1905 Promotion bei Alfred Hoche mit einer Studie über Gedächtnisstörungen bei der Korsakoffschen Psychose. 1905-1906: Assistenzarzt an der Kreisirrenanstalt Karthaus-Prüll, Regensburg. 1906 erscheint die Groteske Lydia und Mäxchen. Tiefe Verbeugung in einem Akt als seine erste Buchveröffentlichung. 1906-1908: Assistenzarzt an der Berliner Städtischen Irrenanstalt in Buch. Beginn der Liebesbeziehung zu der Krankenschwester Frieda Kunke (1891-1918). Wissenschaftliche Publikationen in medizinischen Fachzeitschriften. 1908-1911: Assistenzarzt am Städtischen Krankenhaus Am Urban in Berlin. Dort lernt er die Medizinstudentin Erna Reiss (1888-1957), seine spätere Frau, kennen. 1910: Herwarth Waldens Zeitschrift 'Der Sturm' beginnt zu erscheinen. Döblin gehört bis 1915 zu ihren wichtigsten Mitarbeitern. 1911: Eröffnung einer Kassenpraxis am Halleschen Tor in Berlin (zunächst als praktischer Arzt, später als Nervenarzt und Internist). -

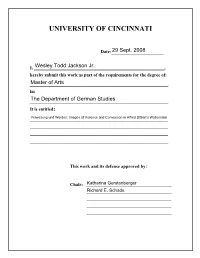

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: ___________________29 Sept. 2008 I, ________________________________________________Wesley Todd Jackson Jr. _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: The Department of German Studies It is entitled : Verwesung und Werden: Images of Violence and Conversion in Alfred Döblin’s Wallenstein This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Katharina Gerstenberger _______________________________Richard E. Schade _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Verwesung und Werden : Images of Violence and Conversion in Alfred Döblin’s Wallenstein A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences By Wesley Todd Jackson Jr., B.A. University of Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America, September 29, 2008 Committee Chair: Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger 2 Abstract This thesis treats the themes of decay and change as represented in Alfred Döblin’s historical novel, Wallenstein . The argument is drawn from the comparison of the verbal images in the text and Döblin’s larger philosophical oeuvre in answer to the question as to why the novel is primarily defined by portrayals of violence, death, and decay. Taking Döblin’s historical, cultural, political, aesthetic, and religious context into account, I demonstrate that Döblin’s use of disturbing images in the novel, complemented by his structurally challenging writing style, functions to challenge traditional views of history and morality, reflect an alternative framework for history and morality based on Döblin’s philosophical observations concerning humankind and its relationship to the natural world, raise awareness of social injustice among readers and, finally, provoke readers to greater social activism and engagement in their surrounding culture. -

GPS Dissertation UPLOAD 18/4/30

“Almost Poetic”: Alfred Döblin’s Subversive Theater Geraldine Poppke Suter Manrode, Germany B.A., Bridgewater College, 2006 M.A., James Madison University, 2008 M.A., University of Virginia, 2013 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures University of Virginia May, 2018 Benjamin K. Bennett Jeffrey A. Grossman Volker Kaiser John L. Parker © 2018 Geraldine Poppke Suter Dedicated to the memory of Hans-Jürgen Wrede “Am Bahnhof stand ein Sauerampfer, sah immer nur Züge und nie einen Dampfer. Armer Sauerampfer.” — Hans-Jürgen Wrede, frei nach Joachim Ringelnatz Abstract This dissertation explores elements of objectification, artistic control, and power in three of Döblin’s plays: Lydia und Mäxchen, Comteß Mizzi, and Die Ehe. In the first chapter I address the nature of, and relationships between, characters and things that people these plays, and outline Döblin’s animation of props, and their elevation to the status of characters in his initial play Lydia und Mäxchen, the objectification of characters in his second play Comteß Mizzi, and a combination thereof in his final play Die Ehe. In the second chapter I treat issues of artistic control. While his debut play contains multiple and unconventional loci of control, the focus of his second play lies on artistic restrictions and its consequences. In his final play Döblin addresses social forces which rule different classes. In the third chapter I connect the elements of objectification and uprising with matters of control by arguing that Döblin employs Marxist themes throughout his plays. -

Mountains Oceans Giants

Alfred Döblin Mountains Oceans Giants An Epic of the 27th Century Translated by C D Godwin Volume One (contains Parts 1 and 2) I know of no attempt in literature that pulls together so boldly and directly the human and the divine, piling on every kind of action, thought, desire, love… Here perhaps the true face of “Expressionism” reveals itself for the first time. – Max Krell Originally published as Berge Meere und Giganten, S.Fischer Verlag, Berlin, 1924 This translation © C D Godwin 2019 This English translation of Alfred Döblin's Berge Meere und Giganten by C D Godwin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Based on the work at https://www.fischerverlage.de/buch/berge_meere_und_giganten/9783596904648 I hereby declare: I have translated this work by Alfred Döblin as a labour of love, out of a desire to bring this writer to wider attention in the English-speaking world. My approaches to UK and US publishing houses have borne no fruit; and so this work, first published in German more than 90 years ago, risks remaining unknown to readers of English. I therefore make it available as a free download from my website https://beyond-alexanderplatz.com under the above CC licence. I acknowledge the rights of S. Fischer Verlag as copyright holder of the source material. I have twice approached S Fischer Verlag regarding copyright permissions for my Döblin translations, but have received no answer; hence my adoption of the most restrictive version of the CC licence. C. D. Godwin 2018 Picture credits (Volume 1) Front cover: Detail from The Temptation of Saint Anthony, by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch. -

Zu Einem Formsemantischen Prinzip Bei Alfred Döblin

Resonantes Erzählen - Zu einem formsemantischen Prinzip bei Alfred Döblin The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Luemers, Arndt. 2016. Resonantes Erzählen - Zu einem formsemantischen Prinzip bei Alfred Döblin. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493436 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Resonantes Erzählen – Zu einem formsemantischen Prinzip bei Alfred Döblin A dissertation presented by Arndt Luemers to The Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Germanic Languages and Literatures Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Arndt Luemers All rights reserved. Prof. Judith Ryan, Prof. Oliver Simons Arndt Luemers Resonantes Erzählen – Zu einem formsemantischen Prinzip bei Alfred Döblin Abstract From the sympathetic vibration of strings to the resonance disasters of collapsing bridges, the physical phenomenon of resonance has fascinated people for centuries. In the 20th century, German writer Alfred Döblin takes up the notion of resonance in his philosophical text Unser Dasein. In Döblin’s understanding of the individual as an ‘open system,’ resonance features as the main natural principle that connects individuals with each other, but also with the world in general. This dissertation investigates the concept of resonance in its anthropological and literary implications for Döblin. -

Giants, Dragons, and the Confrontation with "Den Schrecklichen Mystischen Naturkomplexen" – Apocalyptic Intertextuality in Alfred Döblin's Berge Meere Und Giganten

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2011-12-08 Giants, Dragons, and the Confrontation with "den schrecklichen mystischen Naturkomplexen" – Apocalyptic Intertextuality in Alfred Döblin's Berge Meere und Giganten Nathan J. Bates Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Bates, Nathan J., "Giants, Dragons, and the Confrontation with "den schrecklichen mystischen Naturkomplexen" – Apocalyptic Intertextuality in Alfred Döblin's Berge Meere und Giganten" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 2685. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2685 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Giants, Dragons, and the Confrontation with “den schrecklichen mystischen Naturkomplexen” – Apocalyptic Intertextuality in Alfred Döblin’s Berge Meere und Giganten Nathan Jensen Bates A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Christian Clement, Chair Robert McFarland Thomas Spencer Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages Brigham Young University April 2012 Copyright © 2011 Nathan Jensen Bates All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Giants, Dragons, and the Confrontation with „den schrecklichen mystischen Naturkomplexen” – Apocalyptic Intertextuality in Alfred Döblin’s Berge Meere und Giganten Nathan Bates Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages, BYU Master of Arts Berge Meere und Giganten (BMG) by Alfred Döblin is a fictional account of future events in which humanity brings about the ruin of western civilization by its own technological hubris. -

Bibliographie Der Sekundärliteratur Zu Leben Und Werk Alfred Döblins Seit 1990. Zusammengestellt Von Gabriele Sander (Ein Verz

1 Bibliographie der Sekundärliteratur zu Leben und Werk Alfred Döblins seit 1990. Zusammengestellt von Gabriele Sander (Ein Verzeichnis der Abkürzungen und Siglen für die behandelten Werke findet sich am Schluss.) Abels, Norbert: Der neue Tag war noch nicht da. Zur Konstruktion von Zukunftswelten bei Alfred Döblin und Franz Werfel. In: Die Welt Franz Werfels und die Moral der Völker. Kongressakten des Franz Werfel-Kollo- quiums, Universität Dijon, 18. – 20. Mai 1995. Hrsg. v. Michel Reffet. Bern [u. a.]: Lang 2002, S. 357–392. Akin, Mahmut H.: Alfred Döblin’i Okurken Berlin’i Yasamak. In: Hece. Aylik Edebiyat Dergisi 13 (2009), Heft 147, S. 96–99. [Vor allem zu BA.] Albrecht, Monika: „Spiegel, die immer nur dich zeigen, Kaliban“ – Alfred Döblin und Wolfgang Koeppen aus postkolonialer Sicht. In: Treibhaus 1 (2005), S. 221–238. [Vor allem zu AM.] Alexandre, Philippe: Alfred Döblin et les écrivains allemands en exil, 1933–1945. Images de l’„autre Allemagne“. In: Döblin père et fils, S. 135–152. Alexandre, Philippe: Le Berlin de la fin des années Vingt dans le roman Berlin Alexanderplatz. In: Berlin Alexanderplatz – un roman dans une œuvre, S. 107–127. Althen, Christina: Alfred Döblin. Werk und Wirkung. In: Pommersches Jahrbuch für Literatur 2 (2007), S. 219– 226. Althen, Christina: Alfred Döblin in der Berliner Freien Studentenschaft. Mit unbekannten Briefen und Artikeln Döblins. In: IADK Berlin [II], S. 349–385. Althen, Christina: Alfred Döblin und Theodor Heuss. Mit der Edition einer Rede Döblins bei Theodor Heuss am 30. 5. 1946 und eines Berichts über einen Besuch beim Bundespräsidenten am 1. 4. 1950. In: Neue Rund- schau 122 (2011), Heft 2, S. -

Publikationen A) Monographien: 1. „An Die Grenzen Des Wirklichen Und Möglichen...“. Studien Zu Alfred Döblins Roman Berge

PROF. DR. GABRIELE SANDER Publikationen a) Monographien: 1. „An die Grenzen des Wirklichen und Möglichen...“. Studien zu Alfred Döblins Roman Berge Meere und Giganten. Frankfurt a. M. [u. a.]: Lang, 1988 (Europäische Hochschul- schriften, Reihe 1: Deutsche Sprache und Literatur, Bd. 1099). XII, 634 S. 2. Erläuterungen und Dokumente. Alfred Döblin: Berlin Alexanderplatz. Stuttgart: Reclam, 1998 (Reclam Universal-Bibliothek, Bd. 16009). 288 S. 3. Alfred Döblin. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2001 (Reclam Universal-Bibliothek, Bd. 17632). 397 S. 4a) Sabina Becker, Christine Hummel, Gabriele Sander: Grundkurs Literaturwissenschaft. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2006 (Reclam Universal-Bibliothek, Bd. 17662). 304 S. [Kap. Grundbe- griffe der Edition: S. 15–35; Epik: S. 109–147; Dramatik: S. 148–192.] 4b) 2. erweiterte und aktualisierte Auflage u. d. T. Literaturwissenschaft. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2018 (Reclams Studienbuch Germanistik). 268 S. [Kap. Grundbegriffe der Edition: S. 13–31; Epik: S. 86–126; Dramatik: S. 126–171.] 5. „Tatsachenphantasie“ – Alfred Döblins Roman Berlin Alexanderplatz. Die Geschichte vom Franz Biberkopf. Von Gabriele Sander. Marbach: Deutsche Schillergesellschaft, 2007 (marbacher magazin 119). 86 S. b) Editionen und Sammelbände: 1. Internationales Alfred-Döblin-Kolloquium Leiden 1995. Hrsg. v. Gabriele Sander. Bern [u. a.]: Lang, 1997 (Jahrbuch für Internationale Germanistik, Reihe A: Kongressberichte, Bd. 43). 286 S. 2. Internationales Alfred-Döblin-Kolloquium Leipzig 1997. Hrsg. v. Ira Lorf und Gabriele Sander. Bern [u. a.]: Lang, 1999 (Jahrbuch für Internationale Germanistik, Reihe A: Kongressberichte, Bd. 46). 230 S. 3. Blaue Gedichte. Hrsg. [und mit einem Nachwort] v. Gabriele Sander. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2001 (Reclam Universal-Bibliothek, Bd. 18097). 138 S. 4. Alfred Döblin: Berge Meere und Giganten. Roman. -

Mountains Oceans Giants Manas

Beyond Alexanderplatz FOR THE FIRST TIME IN ENGLISH – TWO ASTONISHING FICTIONAL WORLDS FROM WEIMAR GERMANY MOUNTAINS OCEANS GIANTS (A Dystopia of the 27th Century) and MANAS (A Himalayan Epic in Verse) Translated and introduced by C.D. Godwin April 2020 www.beyond-alexanderplatz.com CONTENTS 1. Why this Introduction? 1 2. Döblin’s life and works 2.1 Alfred Döblin 1878-1957 2 2.2 Döblin’s epic fictions 3 2.3 ‘Happy 140th, Alfred Döblin!’ 4 3. Mountains Oceans Giants [MOG] (1924) 3.1 Alfred Döblin (1941): MOG as a Hollywood film 6 3.2 Gabriele Sander (2013): ‘Afterword’ 13 3.3 Alfred Döblin (1924): ‘Remarks on MOG’ 25 3.4 K. Müller-Salget (1988): Excerpts from Alfred Döblin: Werk and Entwicklung 31 3.5 C.D. Godwin (2019): Why I decided to abridge the English translation 37 4. Manas- a Himalayan Epic (1926) 4.1 C.D. Godwin: The vanished masterpiece 39 4.2 Heinz Graber (1972): On the style of Manas 41 4.2 Four Reviews of Manas – a) Robert Musil (1927) 51 b) Oskar Loerke (1928) 55 c) Axel Eggebrecht (1927) 57 d) W.von Einsiedl (1928) 58 WHY THIS INTRODUCTION? Since his death in 1957, Alfred Döblin’s reputation has grown as one of the 20th century’s great German-language Modernists. A stream of dissertations, monographs reviews and biographies has familiarised German literary journalists and readers with Döblin and his oeuvre, and encouraged the publication of smart new editions (currently the well-curated series from Fischer Klassik). Elsewhere in the world Döblin remains obscure. -

Bibliographie Der Sekundärliteratur Zu Leben Und Werk Alfred Döblins Seit 1990

1 Bibliographie der Sekundärliteratur zu Leben und Werk Alfred Döblins seit 1990. Zusammengestellt von Gabriele Sander (Ein Verzeichnis der Abkürzungen und Siglen für die behandelten Werke findet sich am Schluss.) Abels, Norbert: Der neue Tag war noch nicht da. Zur Konstruktion von Zukunftswelten bei Alfred Döblin und Franz Werfel. In: Die Welt Franz Werfels und die Moral der Völker. Kongressakten des Franz Werfel-Kollo- quiums, Universität Dijon, 18. – 20. Mai 1995. Hrsg. v. Michel Reffet. Bern [u. a.]: Lang 2002, S. 357–392. Abs, Carina: Denkfaule Hoffnung? Anfragen an Erlösungsnarrationen bei Alfred Döblin, Christine Lavant und Friedrich Dürrenmatt. Ostfildern: Matthias Grünewald Verlag 2017. [Kap.: „‚Meine Gedanken lassen nicht von mir‘ – Studien zu literarischen Auseinandersetzungen mit Erlösungsnarrationen“, S. 123–188. [U. a. zu JR, SV, WL, BA und NOV.] Akin, Mahmut H.: Alfred Döblin’i Okurken Berlin’i Yasamak. In: Hece. Aylik Edebiyat Dergisi 13 (2009), Heft 147, S. 96–99. [Vor allem zu BA.] Albrecht, Monika: „Spiegel, die immer nur dich zeigen, Kaliban“ – Alfred Döblin und Wolfgang Koeppen aus postkolonialer Sicht. In: Treibhaus 1 (2005), S. 221–238. [Vor allem zu AM.] Alexandre, Philippe: Alfred Döblin et les écrivains allemands en exil, 1933–1945. Images de l’„autre Allemagne“. In: Döblin père et fils [2009], S. 135–152. Alexandre, Philippe: Le Berlin de la fin des années Vingt dans le roman Berlin Alexanderplatz. In: Berlin Alexanderplatz – un roman dans une œuvre [2011], S. 107–127. Alonso Ímaz, Ma. del Carmen: La percepción de España y la conquista de América en algunas novelas históricas de Richard Friedenthal, Leo Perutz y Alfred Döblin.