Mountains Oceans Giants Manas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

Taking the Cure: a Stay at Thomas Mann's "The Magic Mountain" Philip Bmntingham

Taking the Cure: A Stay at Thomas Mann's "The Magic Mountain" Philip Bmntingham THERE ARE THOSE who say that the human The subject of Shakespeare's play is race is infected by two sicknesses: the the spiritual malaise of one man. In Tho- sickness of the body and the sickness of mas Mann's 1924 novel, The Magic Moun- the spirit. In fact, both afflictions are po- tain, the subject, as so many critics have tentially fatal. The first sickness can be told us, is the malaise of an entire group traced to a number of causes: namely, an of people, indeed a generation. These outside intrusion (infection), or an inner critics—too numerous to mention—have failure (malfunction). The second sick- suggested that Mann's intent was to use ness comes solely from within: emotional illness as a metaphor for the condition of distress, deep anxiety, or that decline pre-World War I European society. sometimes called failure of the will. A Such a theme would be an ambitious mixture of the two sicknesses sometimes one, to be sure. Novels normally do not happens; and it has been proven that the attempt to describe the decay of an entire sickness of the mind often can affect the society—how could they? Novels are not health of the body—and cause what is tracts or scientific reports, and whenever called psychosomatic illness. they attempt to become either of these In Shakespeare's Hamlet, the hero suf- things, such as we find in as Robert Musil's fers from the second sickness, and it de- The Man Without Qualities (1930-43), they bilitates him so much that he contem- are no longer fiction but prose seminars. -

A Study of the Space That Shaped Weimar Berlin Carrie Grace Latimer Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2014 The lotP s of Alexanderplatz: A Study of the Space that Shaped Weimar Berlin Carrie Grace Latimer Scripps College Recommended Citation Latimer, Carrie Grace, "The lotsP of Alexanderplatz: A Study of the Space that Shaped Weimar Berlin" (2014). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 430. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/430 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLOTS OF ALEXANDERPLATZ: A STUDY OF THE SPACE THAT SHAPED WEIMAR BERLIN by CARRIE GRACE LATIMER SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR MARC KATZ PROFESSOR DAVID ROSELLI APRIL 25 2014 Latimer 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Berlin Alexanderplatz: The Making of the Central Transit Hub 8 The Design Behind Alexanderplatz The Spaces of Alexanderplatz Chapter Two: Creative Space: Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz 23 All-Consuming Trauma Biberkopf’s Relationship with the Built Environment Döblin’s Literary Metropolis Chapter Three: Alexanderplatz Exposed: Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Film 39 Berlin from Biberkopf’s Perspective Exposing the Subterranean Trauma Conclusion 53 References 55 Latimer 3 Acknowledgements I wish to thank all the people who contributed to this project. Firstly, to Professor Marc Katz and Professor David Roselli, my thesis readers, for their patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and thoughtful critiques. -

Download Download

Phytopoetics: Upending the Passive Paradigm with Vegetal Violence and Eroticism Joela Jacobs University of Arizona [email protected] Abstract This article develops the notion of phytopoetics, which describes the role of plant agency in literary creations and the cultural imaginary. In order to show how plants prompt poetic productions, the article engages with narratives by modernist German authors Oskar Panizza, Hanns Heinz Ewers, and Alfred Döblin that feature vegetal eroticism and violence. By close reading these texts and their contexts, the article maps the role of plant agency in the co-constitution of a cultural imaginary of the vegetal that results in literary works as well as societal consequences. In this article, I propose the notion of phytopoetics (phyto = relating to or derived from plants, and poiesis = creative production or making), parallel to the concept of zoopoetics.1 Just as zoopoetics describes the role of animals in the creation of texts and language, phytopoetics entails both a poetic engagement with plants in literature and moments in which plants take on literary or cultural agency themselves (see Moe’s [2014] emphasis on agency in zoopoetics, and Marder, 2018). In this understanding, phytopoetics encompasses instances in which plants participate in the production of texts as “material-semiotic nodes or knots” (Haraway, 2008, p. 4) that are neither just metaphor, nor just plant (see Driscoll & Hoffmann, 2018, p. 4 and pp. 6-7). Such phytopoetic effects manifest in the cultural imagination more broadly.2 While most phytopoetic texts are literary, plant behavior has also prompted other kinds of writing, such as scientific or legal Joela Jacobs (2019). -

Frank Martin's Interpretation of the Tristan and Isolde Myth

MARTA SZOKA (Łódź) Frank Martin’s Interpretation of the Tristan and Isolde Myth: Following the Trail of a Certain Novel Some people may frown at a juxtaposition of the Tristan and Isolde myth, one of the greatest sources of artistic inspiration in Euro pean culture, and its numerous musical representations with a novel by Charles Morgan, a minor writer known today almost exclusively to English literature scholars. If, however, we assume that the practice of musicology, apart from the analysis of music in terms of purely sonic structures, embraces also critical reflection, then we can put forward a perspective which will - to quote Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert - ‘open up a dialogue with the maker of the work, with his unique inner world, his love, passion and dilemmas, and also the path of perfection charac teristic of him and given to him’.1 I set out to scrutinise Frank Martin’s work in view of certain cul tural and psychological issues, as well as the social aspect of myth. Taken out of its complex context, the music score is forced to be an autonomous organism, and thus the multidimensional sense of art in the modern world becomes forgotten. Bearing an artistic and cultural message, a work of art is a carrier of meanings beyond the author’s in tent - meanings to be reached and understood. Moreover, this process of reaching out toward meaning does not exhaust itself in a single act of cognition, supposed to establish a certain truth once and for all. I would like to adopt here Hans-Georg Gadamer’s premise of the ‘inexhaustibil ity’ of the meaning of art as well as the ever renewed process of its un derstanding.2 1 Zbigniew Herbert, ‘Willem Duyster (1599-1635) albo Dyskretny urok soldateski’ [Willem Duyster, or the Discreet charm of the soldiery], Zeszyty Literackie 68 (1999), 18. -

Soundscapes of the Urban Past

Sounds Familiar Intermediality and Remediation in the Written, Sonic and Audiovisual Narratives of Berlin Alexanderplatz Andreas Fickers, Jasper Aalbers, Annelies Jacobs and Karin Bijsterveld 1. Introduction When Franz Biberkopf, the protagonist of Alfred Döblin’s novel Berlin Alexanderplatz steps out of the prison in Tegel after four years of imprisonment, »the horrible moment« has arrived. Instead of being delighted about his reclaimed liberty, Biberkopf panics and feels frightened: »the pain commences«.1 He is not afraid of his newly gained freedom itself, however. What he suffers from is the sensation of being exposed to the hectic life and cacophonic noises of the city – his »urban paranoia«.2 The tension between the individual and the city, between the inner life of a character and his metropolitan environment is of course a well established topic in the epic litera- ture of the nineteenth century, often dramatized by the purposeful narrative confronta- tion between city life and its peasant or rural counterpoint.3 But as a new literary genre, the Großstadtroman, or big city novel, only emerges in the early twentieth century, and Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz is often aligned with Andrei Bely’s Petersburg (1916), James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) or John Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer (1925) as an outstanding example of this new genre.4 What distinguishes these novels from earlier writings dealing with the metropolis is their experimentation with new forms of narra- tive composition, often referred to as a »cinematic style« of storytelling. At the same time, however, filmmakers such as David W. Griffiths and Sergei Eisenstein developed 1 Döblin 1961, 13. -

Alfred Döblins Weg

210 -- Sabine Schneider Rutsch, Bettina: Leiblichkeit der Sprache. Sprachlichkeit des Leibes. Wort, Gebärde, Tanz bei Alexander Honold Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Frankfurt a. M. 1998. Schlötterer, Reinhold: ,,Elektras Tanz in der Tragödie Hugo von Hofmannsthals". In: Exotischentgrenzte Kriegslandschaften: Hofmannsthal-Blätter 33 (1986), 5. 47-58. Schneider, Florian: ,,Augenangst? Die Psychoanalyse als ikonoklastische Poetologie". In: Alfred DöblinsWeg zum „Geonarrativ" Hofmannstha/-Jahrbuch 11 (2001), 5. 197- 240. Schneider, Sabine: ,,Das Leuchten der Bilder in der Sprache. Hofmannsthals medienbewusste Berge Meere und Giganten Poetik der Evidenz". In: Hofmannsthal-Jahrbuch 11 (2003), 5. 209-248. Schneider, Sabine: ,,Die Welt der Bezüge. Hofmannsthal zur Autorität des Dichters in seiner Was eigentlich geschieht an den Rändern der durch Atmosphäre, Gravitation und Zeit". In: Colloquium Helveticum 41 (2010), 5. 203-221. Drehbewegung verbundenen Heimatkugel irdischen Lebens? Etwa dann, wenn die Schneider, Sabine: ,,Helldunkel - Elektras Schattenbilder oder die Grenzen der semiotischen zivilisatorischen Makro-Ereignisse von diesem Erdklumpen nicht mehr zusam- Utopie". In: dies.: Verheißung der Bilder. Das andere Medium in der Literatur um 1900. mengehalten werden können? Tübingen 2006, 5. 342- 368. Schneider, Sabine: .,Poetik der Illumination. Hugo von Hofmannsthals Bildreflexionen im Kein Ohr hörte das Schlürfen Schleifen, das seidig volle Wehen an dem fernen Saum. Ge- Gespräch über Gedichte". In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 71 (2008), Heft 3, schüttelt wurde die Luft im Rollen und Stürzen der Kugel, die sie mitschleppte. Lag gedreht an 5. 389-404. der Erde, schmiegte sich gedrückt an dem rasenden Körper an, wehte hinter ihm wie ein Seel, Martin: Die Macht des Erscheinens. Textezur Ästhetik. Frankfurt a. M. 2007. aufgelöster Zopf. (BMG 367)1 Sommer, Manfred: Evidenz im Augenblick. -

Chronik ALFRED DÖBLIN 1878

Leben & Werk - Chronik ALFRED DÖBLIN 1878 - 1957 10. August 1878: Geburt Alfred Döblins in Stettin als viertes und vorletztes Kind jüdischer Eltern, des Schneidermeisters Max Döblin (1846-1921) und seiner Frau Sophie, geb. Freudenheim (1844-1920). 1888: Döblins Vater verlässt Frau und Kinder; die Mutter zieht mit ihren fünf Kindern nach Berlin. 1891-1900: Besuch des Köllnischen Gymnasiums in Berlin. Ausbildung literarischer, philosophischer und musikalischer Neigungen. Lektüre Kleists, Hölderlins, Dostojewskijs, Schopenhauers, Spinozas, Nietzsches. Entstehung erster literarischer und essaysistischer Texte, darunter Alfred Döblin. Kinderfoto um Modern. Ein Bild aus der Gegenwart (1896). 1888 1900: Niederschrift des ersten Romans Jagende Rosse (zu Lebzeiten unveröffentlicht). 1900-1905: Medizinstudium in Berlin und Freiburg i.Br. Beginn der Freundschaft mit Herwarth Walden und Else Lasker-Schüler. Entstehung des zweiten Romans Worte und Zufälle (1902/03; als Buch 1919 unter dem Titel Der schwarze Vorhang veröffentlicht), zweier kritischer Nietzsche Essays (1902/03) und mehrerer Erzählungen, darunter Die Ermordung einer Butterblume. 1905 Promotion bei Alfred Hoche mit einer Studie über Gedächtnisstörungen bei der Korsakoffschen Psychose. 1905-1906: Assistenzarzt an der Kreisirrenanstalt Karthaus-Prüll, Regensburg. 1906 erscheint die Groteske Lydia und Mäxchen. Tiefe Verbeugung in einem Akt als seine erste Buchveröffentlichung. 1906-1908: Assistenzarzt an der Berliner Städtischen Irrenanstalt in Buch. Beginn der Liebesbeziehung zu der Krankenschwester Frieda Kunke (1891-1918). Wissenschaftliche Publikationen in medizinischen Fachzeitschriften. 1908-1911: Assistenzarzt am Städtischen Krankenhaus Am Urban in Berlin. Dort lernt er die Medizinstudentin Erna Reiss (1888-1957), seine spätere Frau, kennen. 1910: Herwarth Waldens Zeitschrift 'Der Sturm' beginnt zu erscheinen. Döblin gehört bis 1915 zu ihren wichtigsten Mitarbeitern. 1911: Eröffnung einer Kassenpraxis am Halleschen Tor in Berlin (zunächst als praktischer Arzt, später als Nervenarzt und Internist). -

Reflections on the Work of Colin Wilson

Reflections on the Work of Colin Wilson Reflections on the Work of Colin Wilson Proceedings of the Second International Colin Wilson Conference University of Nottingham July 6-8, 2018 Edited by Colin Stanley Reflections on the Work of Colin Wilson Edited by Colin Stanley This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Colin Stanley and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2774-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2774-4 CONTENTS Acknowledgement .................................................................................... vii Preface ....................................................................................................... ix Colin Stanley Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 John Morgan Voyager and Dreamer:’s Autobiographical Colin Wilson.......... Writing 7 .. Nicolas Tredell The Evolutionaryhors of Metap Colin Wilson..................... .................... 27 David J. Moore The Outsider and the Work: Coliny ..... Wilson, 41 Gurdjieff and Ouspensk Gary Lachman Consistent Patternsations in of -

Modernism, Fiction and Mathematics

MODERNISM, FICTION AND MATHEMATICS JOHANN A. MAKOWSKY July 15, 2019 Review of: Nina Engelhardt, Modernism, Fiction and Mathematics, Edinburgh Critical Studies in Modernist Culture, Edinburgh University Press, Published June 2018 (Hardback), November 2019 (Paperback) ISBN Paperback: 9781474454841, Hardback: 9781474416238 1. The Book Under Review Nina Engelhardt's book is a study of four novels by three authors, Hermann Broch's trilogy The Sleepwalkers [2, 3], Robert Musil's The Man without Qualities [21, 23, 24], and Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow and Against the Day [27, 28]. Her choice of authors and their novels is motivated by the impact the mathe- matics of the interwar period had on their writing fiction. It is customary in the humanities to describe the cultural ambiance of the interwar period between World War I and World War II as modernism. Hence the title of Engelhardt's book: Mod- ernism, Mathematics and Fiction. Broch and Musil are indeed modernist authors par excellence. Pynchon is a contemporary American author, usually classified by the literary experts as postmodern. arXiv:1907.05787v1 [math.HO] 12 Jul 2019 Hermann Broch in 1909 Robert Musil in 1900 1 2 JOHANN A. MAKOWSKY Thomas Pynchon ca. 1957 Works produced by employees of the United States federal government in the scope of their employment are public domain by statute. Engelhard's book is interesting for the literary minded mathematician for two reasons: First of all it draws attention to three authors who spent a lot of time and thoughts in studying the mathematics of the interwar period and used this experience in the shaping of their respective novels. -

Ein Kleiner, Schwarzer Punkt Am Weisslichen Himmel: Antarctica & Ice in German Expressionism

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2010 Ein kleiner, schwarzer Punkt am weisslichen Himmel: Antarctica & Ice in German Expressionism Joy M. Essigmann University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the German Literature Commons Recommended Citation Essigmann, Joy M., "Ein kleiner, schwarzer Punkt am weisslichen Himmel: Antarctica & Ice in German Expressionism. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/703 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Joy M. Essigmann entitled "Ein kleiner, schwarzer Punkt am weisslichen Himmel: Antarctica & Ice in German Expressionism." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in German. Daniel H. Magilow, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Elisa Schoenbach, Maria Stehle Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Joy M. Essigmann entitled “Ein kleiner, schwarzer Punkt am weisslichen Himmel: Antarctica & Ice in German Expressionism.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in German. -

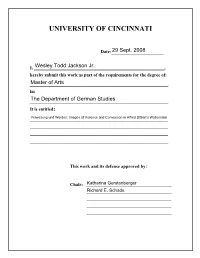

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: ___________________29 Sept. 2008 I, ________________________________________________Wesley Todd Jackson Jr. _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: The Department of German Studies It is entitled : Verwesung und Werden: Images of Violence and Conversion in Alfred Döblin’s Wallenstein This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Katharina Gerstenberger _______________________________Richard E. Schade _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Verwesung und Werden : Images of Violence and Conversion in Alfred Döblin’s Wallenstein A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences By Wesley Todd Jackson Jr., B.A. University of Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America, September 29, 2008 Committee Chair: Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger 2 Abstract This thesis treats the themes of decay and change as represented in Alfred Döblin’s historical novel, Wallenstein . The argument is drawn from the comparison of the verbal images in the text and Döblin’s larger philosophical oeuvre in answer to the question as to why the novel is primarily defined by portrayals of violence, death, and decay. Taking Döblin’s historical, cultural, political, aesthetic, and religious context into account, I demonstrate that Döblin’s use of disturbing images in the novel, complemented by his structurally challenging writing style, functions to challenge traditional views of history and morality, reflect an alternative framework for history and morality based on Döblin’s philosophical observations concerning humankind and its relationship to the natural world, raise awareness of social injustice among readers and, finally, provoke readers to greater social activism and engagement in their surrounding culture.