Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literary Satire and Oskar Panizza's

3 ‘Writing back’: literary satire and Oskar Panizza’s Psichopatia criminalis (1898) Birgit Lang Oskar Panizza’s Psichopatia criminalis (1898) constitutes the most biting parody of the psychiatric case study genre in German literature, and has been praised as a subversive work in the broader context of the anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s and 1970s.1 As a former psy- chiatrist who had been designated for priesthood and later prosecuted in court for blasphemy, Panizza (1853–1921) had intimate knowledge of ‘the three great professions of the Western tradition – law, medicine, and theology – [that] developed practices centred on cases’.2 Psichopatia criminalis for the first time and in literary form problematised the overlap- ping of legal and medical discourse, as well as the interdisciplinary nature of forensics. A short work, Psichopatia criminalis echoes the deterministic reasoning that characterised the psychiatric discourse about creative artists explored in Chapter 2. Panizza’s text is of satirical and even dystopian character. A site of casuistric mastery, it is also the site of the first appearance of Panizza’s doppelgänger, the German Emperor, who became the central figure in the author’s increasingly delusional system of thought. The intrinsic element of judgement that is inherit to the case study genre suited both of these ‘objectives’ well. For a range of reasons Psichopatia criminalis has remained deeply un- comfortable for readers from the very beginning. As this chapter explores, the text has found varying and disparate reading publics. German playwright Heiner Müller (1929–95) affirmatively claimed Panizza as a textual terrorist, and over time various audiences have felt drawn to the theme of political repression in Psichopatia criminalis, without necessar- ily being able to reflect on the link between their attraction and Panizza’s perceived victimisation. -

2015, L: 189-200 Grădina Botanică “Alexandru Borza” Cluj-Napoca

Contribuţii Botanice – 2015, L: 189-200 Grădina Botanică “Alexandru Borza” Cluj-Napoca THE SYMBOLISM OF GARDEN AND ORCHARD PLANTS AND THEIR REPRESENTATION IN PAINTINGS (I) Camelia Paula FĂRCAŞ1, Vasile CRISTEA2, Sorina FĂRCAŞ3, Tudor Mihai URSU3, Anamaria ROMAN3 1.University of Art and Design, Faculty of Visual Arts, Painting Department, 31 Piaţa Unirii, RO-400098 Cluj-Napoca, Romania 2.Babeş-Bolyai University, Department of Taxonomy and Ecology, “Al. Borza”Botanical Garden, 42 Republicii Street RO-400015 Cluj-Napoca, Romania 3.Institute of Biological Research, Branch of the National Institute of Research and Development for Biological Sciences, 48 Republicii Street, RO-400015 Cluj-Napoca, Romania e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Plant symbols are a part of the cultural treasure of humanity, whether we consider the archaic secular traditions or religion, heraldry etc., throughout history until the present day. To flowers, in particular, there have been attributed particular meanings over thousands of years. Every art form has involved flower symbols at some point, but in painting they have an outstanding presence. Early paintings are rich in philosophical and Christian plant symbolism, while 18th–20th century art movements have added new meanings to vegetal-floral symbolism, through the personal perspective of various artists in depicting plant symbols. This paper focuses on the analysis of the ancient plant significance of the heathen traditions and superstitions but also on their religious sense, throughout the ages and cultures. Emphasis has been placed on plants that were illustrated preferentially by painters in their works on gardens and orchards. Keywords: Plant symbolism, paintings, gardens, orchards. Introduction Plant symbols comprise a code of great richness and variety in the cultural thesaurus of humanity. -

Image and Meaning in the Floral Borders of the Hours of Catherine of Cleves Elizabeth R

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1987 Image and Meaning in the Floral Borders of the Hours of Catherine of Cleves Elizabeth R. Schaeffer Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Art at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Schaeffer, Elizabeth R., "Image and Meaning in the Floral Borders of the Hours of Catherine of Cleves" (1987). Masters Theses. 1271. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1271 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. *****US Copyright Notice***** No further reproduction or distribution of this copy is permitted by electronic transmission or any other means. The user should review the copyright notice on the following scanned image(s) contained in the original work from which this electronic copy was made. Section 108: United States Copyright Law The copyright law of the United States [Title 17, United States Code] governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that use may be liable for copyright infringement. -

Alfred Döblins Weg

210 -- Sabine Schneider Rutsch, Bettina: Leiblichkeit der Sprache. Sprachlichkeit des Leibes. Wort, Gebärde, Tanz bei Alexander Honold Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Frankfurt a. M. 1998. Schlötterer, Reinhold: ,,Elektras Tanz in der Tragödie Hugo von Hofmannsthals". In: Exotischentgrenzte Kriegslandschaften: Hofmannsthal-Blätter 33 (1986), 5. 47-58. Schneider, Florian: ,,Augenangst? Die Psychoanalyse als ikonoklastische Poetologie". In: Alfred DöblinsWeg zum „Geonarrativ" Hofmannstha/-Jahrbuch 11 (2001), 5. 197- 240. Schneider, Sabine: ,,Das Leuchten der Bilder in der Sprache. Hofmannsthals medienbewusste Berge Meere und Giganten Poetik der Evidenz". In: Hofmannsthal-Jahrbuch 11 (2003), 5. 209-248. Schneider, Sabine: ,,Die Welt der Bezüge. Hofmannsthal zur Autorität des Dichters in seiner Was eigentlich geschieht an den Rändern der durch Atmosphäre, Gravitation und Zeit". In: Colloquium Helveticum 41 (2010), 5. 203-221. Drehbewegung verbundenen Heimatkugel irdischen Lebens? Etwa dann, wenn die Schneider, Sabine: ,,Helldunkel - Elektras Schattenbilder oder die Grenzen der semiotischen zivilisatorischen Makro-Ereignisse von diesem Erdklumpen nicht mehr zusam- Utopie". In: dies.: Verheißung der Bilder. Das andere Medium in der Literatur um 1900. mengehalten werden können? Tübingen 2006, 5. 342- 368. Schneider, Sabine: .,Poetik der Illumination. Hugo von Hofmannsthals Bildreflexionen im Kein Ohr hörte das Schlürfen Schleifen, das seidig volle Wehen an dem fernen Saum. Ge- Gespräch über Gedichte". In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 71 (2008), Heft 3, schüttelt wurde die Luft im Rollen und Stürzen der Kugel, die sie mitschleppte. Lag gedreht an 5. 389-404. der Erde, schmiegte sich gedrückt an dem rasenden Körper an, wehte hinter ihm wie ein Seel, Martin: Die Macht des Erscheinens. Textezur Ästhetik. Frankfurt a. M. 2007. aufgelöster Zopf. (BMG 367)1 Sommer, Manfred: Evidenz im Augenblick. -

Garden for the Future in This Issue

Friends of Bendigo Botanic Gardens Inc. Newsletter Issue 5, Autumn 2017 Garden for the Future In this issue: 1 Contents and Progress on the BBG Master Plan 2-3 The Deer Statue - Helen Hickey 4-6 Floriography - Brad Creme Builders’ huts and fencing in place Plants ready for GFTF (curator) Stage 2 of the Master plan 6 A Tale of two Koels - Anne Works on the Garden for the Future are underway. The outreach shelter at the south end will be Bridley the first area to be constructed with works continuing to progress northwards. The earthworks will soon start to take shape. 2017 is the 160th anniversary of the Bendigo Botanic Gardens, 7 What have we here? Jan Orr White Hills and it is fitting that after a decade of progress since the 150th anniversary, we will finally have a contemporary and dynamic expansion of the gardens being built this year. 8 What’s on A lot has been said already on the tourism, commercialisation and events that the project will facilitate but I’d like to talk about the horticulture and the landscape design. TCL and Paul Thompson have developed the concept and plant list based on certain design themes. Some of the key themes that you’ll see in the finished garden include combinations/parallels/opposites, the simple and the diverse, the hardy and the non-hardy, the known and the unknown, the common and the uncommon, the reliable and the experimental, the structural and the ephemeral. First time visitors will learn how to ‘climate-change-proof ’ their garden using careful plant selection and plants which will survive Bendigo’s extreme weather conditions with temperatures ranging from -4 to 46 degrees. -

Chronik ALFRED DÖBLIN 1878

Leben & Werk - Chronik ALFRED DÖBLIN 1878 - 1957 10. August 1878: Geburt Alfred Döblins in Stettin als viertes und vorletztes Kind jüdischer Eltern, des Schneidermeisters Max Döblin (1846-1921) und seiner Frau Sophie, geb. Freudenheim (1844-1920). 1888: Döblins Vater verlässt Frau und Kinder; die Mutter zieht mit ihren fünf Kindern nach Berlin. 1891-1900: Besuch des Köllnischen Gymnasiums in Berlin. Ausbildung literarischer, philosophischer und musikalischer Neigungen. Lektüre Kleists, Hölderlins, Dostojewskijs, Schopenhauers, Spinozas, Nietzsches. Entstehung erster literarischer und essaysistischer Texte, darunter Alfred Döblin. Kinderfoto um Modern. Ein Bild aus der Gegenwart (1896). 1888 1900: Niederschrift des ersten Romans Jagende Rosse (zu Lebzeiten unveröffentlicht). 1900-1905: Medizinstudium in Berlin und Freiburg i.Br. Beginn der Freundschaft mit Herwarth Walden und Else Lasker-Schüler. Entstehung des zweiten Romans Worte und Zufälle (1902/03; als Buch 1919 unter dem Titel Der schwarze Vorhang veröffentlicht), zweier kritischer Nietzsche Essays (1902/03) und mehrerer Erzählungen, darunter Die Ermordung einer Butterblume. 1905 Promotion bei Alfred Hoche mit einer Studie über Gedächtnisstörungen bei der Korsakoffschen Psychose. 1905-1906: Assistenzarzt an der Kreisirrenanstalt Karthaus-Prüll, Regensburg. 1906 erscheint die Groteske Lydia und Mäxchen. Tiefe Verbeugung in einem Akt als seine erste Buchveröffentlichung. 1906-1908: Assistenzarzt an der Berliner Städtischen Irrenanstalt in Buch. Beginn der Liebesbeziehung zu der Krankenschwester Frieda Kunke (1891-1918). Wissenschaftliche Publikationen in medizinischen Fachzeitschriften. 1908-1911: Assistenzarzt am Städtischen Krankenhaus Am Urban in Berlin. Dort lernt er die Medizinstudentin Erna Reiss (1888-1957), seine spätere Frau, kennen. 1910: Herwarth Waldens Zeitschrift 'Der Sturm' beginnt zu erscheinen. Döblin gehört bis 1915 zu ihren wichtigsten Mitarbeitern. 1911: Eröffnung einer Kassenpraxis am Halleschen Tor in Berlin (zunächst als praktischer Arzt, später als Nervenarzt und Internist). -

The Human Body and the Plant World: Mutual Relations of the Codes (1)

The Human Body and the Plant World 123 The Human Body and the Plant World: Mutual Relations of the Codes (1) Valeria B. Kolosova Institute for Linguistics St. Petersburg, Russia Abstract The article analyses reflections of the anthropomorphic code in the plant code of traditional Slavonic culture. There exist: 1) the language level (using body parts names in phytonyms); 2) the folklore level (aetiological stories about the genesis of plants from the human body); and 3) the level of ritual (using body parts to influence the plants, rules and taboos concerning planting). Plants are also used to influence the human body (usually in folk medicine) on the basis of similarity of their parts. A common principle stands behind this “anthropomorphization” on all three levels—it semioticizes the objective features of a plant. In the “ideal” case, there is a phytonym using a body part in the naming of a plant, an aetiological story about the plant, and rules for using it. Anthropomorphization structures and regulates the sum of knowledge about the plant world. However, this is not just a question of the mutual relations between the two codes, but a part of the system, where sustainability is maintained in at least two ways: the “vertical” (the possibility of expressing the same sense in a text, a word, and a ritual), and the “horizontal” (the possibility of expressing the same sense in different codes). That demonstrates the systematic character of the mythological world model. Never plant a birch or a fir tree near your house, peasants in East Slav areas would advise, because it will drive the women from the house. -

Paradise Gardens

PARADISE GARDENS 001-005 Paradise Gardens PRELIMS.indd 1 23/01/2015 15:44 Pharaoh Hatshepsut’s funerary monument Deir el Bahari, Egypt Djeser-Djeseru was designed by architect The pool was planted with papyrus which was Senenmout and is located on the west bank of believed to be another home of Hathor and in a the Nile and aligned onto the Temple of Amun temple setting was used in both its dedication (a local Theban god) on the opposite bank at and during funerary rites. Around the pools Karnak. Rising in terraces Hatshepsut’s temple about 66 pits were cut into the rock and probably merges into the sheer limestone cliffs of Deir planted with trees to form a shady grove. el Bahari in which it was believed Hathor On the second and third terrace Hatshepsut resided. From the river and leading up to the appears in statue form as Osiris. Within the second terrace was an avenue lined with 120 innermost shrine on the upper terrace are two huge statues at 10 metre spacings. Depicting wall carvings showing a fish pool planted with the queen as a sphinx, they represented the lotus beside which are gardens devoted to power of Egypt and acted as guardians of the growing bitter lettuce (Lactuca serriola), a approach, which was also lined from the river perceived aphrodisiac and sacred to the phallic to the outer court with an avenue of trees. creation divinity Amun-Min. Here too is Either side of the gateway leading into this depicted the first record of plant hunting. -

Oskar Panizza, the Council of Love (1895)

Volume 5. Wilhelmine Germany and the First World War, 1890-1918 Oskar Panizza, The Council of Love (1895) Oskar Panizza (1854-1921) was jailed for writing the play The Council of Love (1895), a scathing critique of the Catholic Church, which was first performed only at the end of his lifetime. Panizza was a Bavarian; his father was a Catholic of Italian extraction and his mother was a converted Pietist. His main targets were Catholic clerical authority and traditionalism, both of which had reemerged in the Catholic areas of Germany as part of the so-called Catholic Revival. After a year in jail, Panizza fled to Switzerland only to return a few years later to Bavaria, where he remained a literary failure and persona non grata. In Memory of [Ulrich von] Hutten “It has been pleasing to God in our days to send upon us diseases (it can, indeed, be noted) that were unknown to our ancestors. And in this, those who hold to the Holy Scriptures have said that smallpox has come from God’s wrath, and that God in this way punishes and torments our evil deeds.” – Ulrich von Hutten, German knight “About the French or Smallpox” 1519 “Dic Dea, quae causae nobis post saecula tanta insolitam peperere luem? . ” – Fracastoro “Syphilis sive de morbo Gallico” 1509 Characters in the Play God the Father Jesus Christ Maria The Devil The Woman A Cherub First Angel Second Angel Third Angel Figures from the Realm of the Dead Helena Phryne Héloise Agrippina Salome Rodrigo Borgia, Alexander VI, Pope Children of the Pope Girolama Borgia, married to Cesarini Isabella Borgia, married to Matuzzi (mother unknown) Pier Luigi Borgia, Duke of Gandia Don Giovanni Borgia, Count of Celano Cesare Borgia, Duke of Romagna Don Gioffre Borgia, Count of Cariati Donna Lucrezia Borgia, Dutchess of Bisaglie (of the Vanozza) Act I, Scene I Heaven, a throne room; three angels in swan-white, quilt-like suits with tight-fitting knee- breeches similar to spats, knee-length stockings, short cupid wings, hair powdered white and cut short, satin shoes; they have feather-dusters in their hands for dusting. -

Literary Satire and Oskar Panizza's

3 ‘Writing back’: literary satire and Oskar Panizza’s Psichopatia criminalis (1898) Birgit Lang Oskar Panizza’s Psichopatia criminalis (1898) constitutes the most biting parody of the psychiatric case study genre in German literature, and has been praised as a subversive work in the broader context of the anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s and 1970s.1 As a former psy- chiatrist who had been designated for priesthood and later prosecuted in court for blasphemy, Panizza (1853–1921) had intimate knowledge of ‘the three great professions of the Western tradition – law, medicine, and theology – [that] developed practices centred on cases’.2 Psichopatia criminalis for the first time and in literary form problematised the overlap- ping of legal and medical discourse, as well as the interdisciplinary nature of forensics. A short work, Psichopatia criminalis echoes the deterministic reasoning that characterised the psychiatric discourse about creative artists explored in Chapter 2. Panizza’s text is of satirical and even dystopian character. A site of casuistric mastery, it is also the site of the first appearance of Panizza’s doppelgänger, the German Emperor, who became the central figure in the author’s increasingly delusional system of thought. The intrinsic element of judgement that is inherit to the case study genre suited both of these ‘objectives’ well. For a range of reasons Psichopatia criminalis has remained deeply un- comfortable for readers from the very beginning. As this chapter explores, the text has found varying and disparate reading publics. German playwright Heiner Müller (1929–95) affirmatively claimed Panizza as a textual terrorist, and over time various audiences have felt drawn to the theme of political repression in Psichopatia criminalis, without necessar- ily being able to reflect on the link between their attraction and Panizza’s perceived victimisation. -

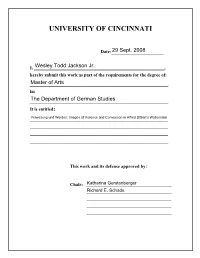

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: ___________________29 Sept. 2008 I, ________________________________________________Wesley Todd Jackson Jr. _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: The Department of German Studies It is entitled : Verwesung und Werden: Images of Violence and Conversion in Alfred Döblin’s Wallenstein This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Katharina Gerstenberger _______________________________Richard E. Schade _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Verwesung und Werden : Images of Violence and Conversion in Alfred Döblin’s Wallenstein A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences By Wesley Todd Jackson Jr., B.A. University of Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America, September 29, 2008 Committee Chair: Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger 2 Abstract This thesis treats the themes of decay and change as represented in Alfred Döblin’s historical novel, Wallenstein . The argument is drawn from the comparison of the verbal images in the text and Döblin’s larger philosophical oeuvre in answer to the question as to why the novel is primarily defined by portrayals of violence, death, and decay. Taking Döblin’s historical, cultural, political, aesthetic, and religious context into account, I demonstrate that Döblin’s use of disturbing images in the novel, complemented by his structurally challenging writing style, functions to challenge traditional views of history and morality, reflect an alternative framework for history and morality based on Döblin’s philosophical observations concerning humankind and its relationship to the natural world, raise awareness of social injustice among readers and, finally, provoke readers to greater social activism and engagement in their surrounding culture. -

Cuando La Psiquiatría No Libera Ni Alivia: La Dramática Vida De Un Psiquiatra Escritor *

ARTÍCULO ESPECIAL / SPECIAL ARTICLE Cuando la psiquiatría no libera ni alivia: la dramática vida de un psiquiatra escritor *. When Psychiatry neither liberates nor alleviates: The dramatic life of a psychiatrist-writer. Héctor Pérez-Rincón García 1 RESUMEN Dentro del numeroso grupo de psiquiatras-escritores a lo largo de la historia, se examina la vida y obra de Oskar Panizza (1853-1921), nacido en Baviera, condiscípulo de Kraepelin, alumno de von Gudden y promisor clínico e investigador que, sin embargo, prefirió y persiguió intensamente una profunda vocación literaria. Autor de novelas, ensayos y obras de teatro, Panizza exhibió un temperamento audaz, carácter apasionado y crítico que tradujo en sus obras y en una creciente actividad periodística en la que emergió también clara ideación paranoide, experiencias alucinatorias y violencia dirigida contra autoridades políticas y religiosas de Alemania y Europa. Había contraido sífilis en sus años jóvenes y por ello, se plantean posibilidades diagnósticas de trastorno mental vinculada a esta enfermedad o a un cuadro psicótico de fondo. Murió pobre y abandonado en un hospital psiquiátrico de Bayreuth. Su obra ha recibido reconocimiento tardío como precursora de conceptos académicos modernos de antropología sexual y pensamiento psico-filosófico. PALABRAS CLAVE: Literatura y Psiquiatria, creatividad, sífilis, psicosis. SUMMARY Within the numerous group of psychiatrist-writers across history, the life and work of Oskar Panizza (1853-1921) are examined. Born in Bavaria, a classmate of Kraepelin in medical school and, a disciple of von Gudden and a promising clinican/investigator, Panizza, however, pursued an intense literary vocation and wrote novels, essays and plays. He exhibited a bold temperament, a passionate and critical carácter that transferred to his Works and to a growing journalistic activity in which also emerged a clear paranoid ideation, hallucinatory experiences and violence directed against politial and religious authorities from Germany and Europe.