Gelderloos, Carl Characters As Collectives in Döblin's Wallenstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

A Study of the Space That Shaped Weimar Berlin Carrie Grace Latimer Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2014 The lotP s of Alexanderplatz: A Study of the Space that Shaped Weimar Berlin Carrie Grace Latimer Scripps College Recommended Citation Latimer, Carrie Grace, "The lotsP of Alexanderplatz: A Study of the Space that Shaped Weimar Berlin" (2014). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 430. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/430 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLOTS OF ALEXANDERPLATZ: A STUDY OF THE SPACE THAT SHAPED WEIMAR BERLIN by CARRIE GRACE LATIMER SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR MARC KATZ PROFESSOR DAVID ROSELLI APRIL 25 2014 Latimer 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Berlin Alexanderplatz: The Making of the Central Transit Hub 8 The Design Behind Alexanderplatz The Spaces of Alexanderplatz Chapter Two: Creative Space: Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz 23 All-Consuming Trauma Biberkopf’s Relationship with the Built Environment Döblin’s Literary Metropolis Chapter Three: Alexanderplatz Exposed: Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Film 39 Berlin from Biberkopf’s Perspective Exposing the Subterranean Trauma Conclusion 53 References 55 Latimer 3 Acknowledgements I wish to thank all the people who contributed to this project. Firstly, to Professor Marc Katz and Professor David Roselli, my thesis readers, for their patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and thoughtful critiques. -

Download Download

Phytopoetics: Upending the Passive Paradigm with Vegetal Violence and Eroticism Joela Jacobs University of Arizona [email protected] Abstract This article develops the notion of phytopoetics, which describes the role of plant agency in literary creations and the cultural imaginary. In order to show how plants prompt poetic productions, the article engages with narratives by modernist German authors Oskar Panizza, Hanns Heinz Ewers, and Alfred Döblin that feature vegetal eroticism and violence. By close reading these texts and their contexts, the article maps the role of plant agency in the co-constitution of a cultural imaginary of the vegetal that results in literary works as well as societal consequences. In this article, I propose the notion of phytopoetics (phyto = relating to or derived from plants, and poiesis = creative production or making), parallel to the concept of zoopoetics.1 Just as zoopoetics describes the role of animals in the creation of texts and language, phytopoetics entails both a poetic engagement with plants in literature and moments in which plants take on literary or cultural agency themselves (see Moe’s [2014] emphasis on agency in zoopoetics, and Marder, 2018). In this understanding, phytopoetics encompasses instances in which plants participate in the production of texts as “material-semiotic nodes or knots” (Haraway, 2008, p. 4) that are neither just metaphor, nor just plant (see Driscoll & Hoffmann, 2018, p. 4 and pp. 6-7). Such phytopoetic effects manifest in the cultural imagination more broadly.2 While most phytopoetic texts are literary, plant behavior has also prompted other kinds of writing, such as scientific or legal Joela Jacobs (2019). -

Soundscapes of the Urban Past

Sounds Familiar Intermediality and Remediation in the Written, Sonic and Audiovisual Narratives of Berlin Alexanderplatz Andreas Fickers, Jasper Aalbers, Annelies Jacobs and Karin Bijsterveld 1. Introduction When Franz Biberkopf, the protagonist of Alfred Döblin’s novel Berlin Alexanderplatz steps out of the prison in Tegel after four years of imprisonment, »the horrible moment« has arrived. Instead of being delighted about his reclaimed liberty, Biberkopf panics and feels frightened: »the pain commences«.1 He is not afraid of his newly gained freedom itself, however. What he suffers from is the sensation of being exposed to the hectic life and cacophonic noises of the city – his »urban paranoia«.2 The tension between the individual and the city, between the inner life of a character and his metropolitan environment is of course a well established topic in the epic litera- ture of the nineteenth century, often dramatized by the purposeful narrative confronta- tion between city life and its peasant or rural counterpoint.3 But as a new literary genre, the Großstadtroman, or big city novel, only emerges in the early twentieth century, and Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz is often aligned with Andrei Bely’s Petersburg (1916), James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) or John Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer (1925) as an outstanding example of this new genre.4 What distinguishes these novels from earlier writings dealing with the metropolis is their experimentation with new forms of narra- tive composition, often referred to as a »cinematic style« of storytelling. At the same time, however, filmmakers such as David W. Griffiths and Sergei Eisenstein developed 1 Döblin 1961, 13. -

Alfred Döblins Weg

210 -- Sabine Schneider Rutsch, Bettina: Leiblichkeit der Sprache. Sprachlichkeit des Leibes. Wort, Gebärde, Tanz bei Alexander Honold Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Frankfurt a. M. 1998. Schlötterer, Reinhold: ,,Elektras Tanz in der Tragödie Hugo von Hofmannsthals". In: Exotischentgrenzte Kriegslandschaften: Hofmannsthal-Blätter 33 (1986), 5. 47-58. Schneider, Florian: ,,Augenangst? Die Psychoanalyse als ikonoklastische Poetologie". In: Alfred DöblinsWeg zum „Geonarrativ" Hofmannstha/-Jahrbuch 11 (2001), 5. 197- 240. Schneider, Sabine: ,,Das Leuchten der Bilder in der Sprache. Hofmannsthals medienbewusste Berge Meere und Giganten Poetik der Evidenz". In: Hofmannsthal-Jahrbuch 11 (2003), 5. 209-248. Schneider, Sabine: ,,Die Welt der Bezüge. Hofmannsthal zur Autorität des Dichters in seiner Was eigentlich geschieht an den Rändern der durch Atmosphäre, Gravitation und Zeit". In: Colloquium Helveticum 41 (2010), 5. 203-221. Drehbewegung verbundenen Heimatkugel irdischen Lebens? Etwa dann, wenn die Schneider, Sabine: ,,Helldunkel - Elektras Schattenbilder oder die Grenzen der semiotischen zivilisatorischen Makro-Ereignisse von diesem Erdklumpen nicht mehr zusam- Utopie". In: dies.: Verheißung der Bilder. Das andere Medium in der Literatur um 1900. mengehalten werden können? Tübingen 2006, 5. 342- 368. Schneider, Sabine: .,Poetik der Illumination. Hugo von Hofmannsthals Bildreflexionen im Kein Ohr hörte das Schlürfen Schleifen, das seidig volle Wehen an dem fernen Saum. Ge- Gespräch über Gedichte". In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 71 (2008), Heft 3, schüttelt wurde die Luft im Rollen und Stürzen der Kugel, die sie mitschleppte. Lag gedreht an 5. 389-404. der Erde, schmiegte sich gedrückt an dem rasenden Körper an, wehte hinter ihm wie ein Seel, Martin: Die Macht des Erscheinens. Textezur Ästhetik. Frankfurt a. M. 2007. aufgelöster Zopf. (BMG 367)1 Sommer, Manfred: Evidenz im Augenblick. -

Chronik ALFRED DÖBLIN 1878

Leben & Werk - Chronik ALFRED DÖBLIN 1878 - 1957 10. August 1878: Geburt Alfred Döblins in Stettin als viertes und vorletztes Kind jüdischer Eltern, des Schneidermeisters Max Döblin (1846-1921) und seiner Frau Sophie, geb. Freudenheim (1844-1920). 1888: Döblins Vater verlässt Frau und Kinder; die Mutter zieht mit ihren fünf Kindern nach Berlin. 1891-1900: Besuch des Köllnischen Gymnasiums in Berlin. Ausbildung literarischer, philosophischer und musikalischer Neigungen. Lektüre Kleists, Hölderlins, Dostojewskijs, Schopenhauers, Spinozas, Nietzsches. Entstehung erster literarischer und essaysistischer Texte, darunter Alfred Döblin. Kinderfoto um Modern. Ein Bild aus der Gegenwart (1896). 1888 1900: Niederschrift des ersten Romans Jagende Rosse (zu Lebzeiten unveröffentlicht). 1900-1905: Medizinstudium in Berlin und Freiburg i.Br. Beginn der Freundschaft mit Herwarth Walden und Else Lasker-Schüler. Entstehung des zweiten Romans Worte und Zufälle (1902/03; als Buch 1919 unter dem Titel Der schwarze Vorhang veröffentlicht), zweier kritischer Nietzsche Essays (1902/03) und mehrerer Erzählungen, darunter Die Ermordung einer Butterblume. 1905 Promotion bei Alfred Hoche mit einer Studie über Gedächtnisstörungen bei der Korsakoffschen Psychose. 1905-1906: Assistenzarzt an der Kreisirrenanstalt Karthaus-Prüll, Regensburg. 1906 erscheint die Groteske Lydia und Mäxchen. Tiefe Verbeugung in einem Akt als seine erste Buchveröffentlichung. 1906-1908: Assistenzarzt an der Berliner Städtischen Irrenanstalt in Buch. Beginn der Liebesbeziehung zu der Krankenschwester Frieda Kunke (1891-1918). Wissenschaftliche Publikationen in medizinischen Fachzeitschriften. 1908-1911: Assistenzarzt am Städtischen Krankenhaus Am Urban in Berlin. Dort lernt er die Medizinstudentin Erna Reiss (1888-1957), seine spätere Frau, kennen. 1910: Herwarth Waldens Zeitschrift 'Der Sturm' beginnt zu erscheinen. Döblin gehört bis 1915 zu ihren wichtigsten Mitarbeitern. 1911: Eröffnung einer Kassenpraxis am Halleschen Tor in Berlin (zunächst als praktischer Arzt, später als Nervenarzt und Internist). -

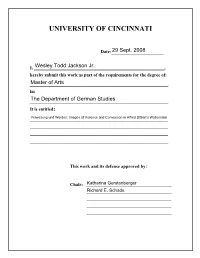

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: ___________________29 Sept. 2008 I, ________________________________________________Wesley Todd Jackson Jr. _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: The Department of German Studies It is entitled : Verwesung und Werden: Images of Violence and Conversion in Alfred Döblin’s Wallenstein This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Katharina Gerstenberger _______________________________Richard E. Schade _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Verwesung und Werden : Images of Violence and Conversion in Alfred Döblin’s Wallenstein A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences By Wesley Todd Jackson Jr., B.A. University of Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America, September 29, 2008 Committee Chair: Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger 2 Abstract This thesis treats the themes of decay and change as represented in Alfred Döblin’s historical novel, Wallenstein . The argument is drawn from the comparison of the verbal images in the text and Döblin’s larger philosophical oeuvre in answer to the question as to why the novel is primarily defined by portrayals of violence, death, and decay. Taking Döblin’s historical, cultural, political, aesthetic, and religious context into account, I demonstrate that Döblin’s use of disturbing images in the novel, complemented by his structurally challenging writing style, functions to challenge traditional views of history and morality, reflect an alternative framework for history and morality based on Döblin’s philosophical observations concerning humankind and its relationship to the natural world, raise awareness of social injustice among readers and, finally, provoke readers to greater social activism and engagement in their surrounding culture. -

GERMAN MASQUERADE Part 2

Beyond Alexanderplatz ALFRED DÖBLIN GERMAN MASQUERADE WRITINGS ON POLITICS, LIFE, AND LITERATURE IN CHAOTIC TIMES Part 2: Politics and Society Edited and translated by C.D. Godwin https://beyond-alexanderplatz.com Alfred Döblin (10 August 1878 – 26 June 1957) has only slowly become recognised as one of the greatest 20th century writers in German. His works encompass epic fictions, novels, short stories, political essays and journalism, natural philosophy, the theory and practice of literary creation, and autobiographical excursions. His many-sided, controversial and even contradictory ideas made him a lightning-conductor for the philosophical and political confusions that permeated 20th century Europe. Smart new editions of Döblin’s works appear every decade or two in German, and a stream of dissertations and major overviews reveal his achievements in more nuanced ways than earlier critiques polarised between hagiography and ignorant dismissal. In the Anglosphere Döblin remains known, if at all, for only one work: Berlin Alexanderplatz. Those few of his other works that have been translated into English are not easily found. Hence publishers, editors and critics have no easy basis to evaluate his merits, and “because Döblin is unknown, he shall remain unknown.” Döblin’s non-fiction writings provide indispensable glimpses into his mind and character as he grapples with catastrophes, confusions and controversies in his own life and in the wider world of the chaotic 20th century. C. D. Godwin translated Döblin’s first great epic novel, The Three Leaps of Wang Lun, some 30 years ago (2nd ed. NY Review Books 2015). Since retiring in 2012 he has translated four more Döblin epics (Wallenstein, Mountains Oceans Giants, Manas, and The Amazonas Trilogy) as well as numerous essays. -

GPS Dissertation UPLOAD 18/4/30

“Almost Poetic”: Alfred Döblin’s Subversive Theater Geraldine Poppke Suter Manrode, Germany B.A., Bridgewater College, 2006 M.A., James Madison University, 2008 M.A., University of Virginia, 2013 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures University of Virginia May, 2018 Benjamin K. Bennett Jeffrey A. Grossman Volker Kaiser John L. Parker © 2018 Geraldine Poppke Suter Dedicated to the memory of Hans-Jürgen Wrede “Am Bahnhof stand ein Sauerampfer, sah immer nur Züge und nie einen Dampfer. Armer Sauerampfer.” — Hans-Jürgen Wrede, frei nach Joachim Ringelnatz Abstract This dissertation explores elements of objectification, artistic control, and power in three of Döblin’s plays: Lydia und Mäxchen, Comteß Mizzi, and Die Ehe. In the first chapter I address the nature of, and relationships between, characters and things that people these plays, and outline Döblin’s animation of props, and their elevation to the status of characters in his initial play Lydia und Mäxchen, the objectification of characters in his second play Comteß Mizzi, and a combination thereof in his final play Die Ehe. In the second chapter I treat issues of artistic control. While his debut play contains multiple and unconventional loci of control, the focus of his second play lies on artistic restrictions and its consequences. In his final play Döblin addresses social forces which rule different classes. In the third chapter I connect the elements of objectification and uprising with matters of control by arguing that Döblin employs Marxist themes throughout his plays. -

"Berlin-Alexanderplatz" by Alfred Döblin

ISSN 2414-8385 (Online) European Journal of January-April 2018 ISSN 2414-8377 (Print Multidisciplinary Studies Volume 3, Issue 2 Prison as a Heterotopia in the Roman "Berlin-Alexanderplatz" by Alfred Döblin Asst. Prof. Dr. Zennube Şahin Yılmaz Faculty of Philological, Atatürk University Abstract One of the biggest problems of modern times and modern literature is the big city. The big city problems are accepted as a motive of modern literature. These problems and the prison are concretized in the novel "Berlin- Alexanderplatz" by Alfred Döblin. The prison in the novel is taken with regard to Michel Foucault's heterotopic perspective or concept. On this occasion stands the relationship of the main character with the prison in the foreground in the analysis of the novel. The society is the origin of the mental problems of the figure seen in the novel. The figure is in a confrontation with society and actually with itself. Because of this, the complexity of the subject with society is taken into consideration by the perception of the city and the attempt to overcome the urban problems. The figure seeks for itself a space other than society. The prison is referred to as another room and the meaning of the prison is described as heterotopia. In addition, the novel is analyzed with Döblin's language or narrative style. Because the construction of the novel gives the narrator a special value. From the narrator, the heterotopic meaning of the prison is elucidated. Keywords: Heterotopia -Prison, society, mental problems. Introduction The meaning of spaces or perception of space is changing nowadays. -

Mountains Oceans Giants

Alfred Döblin Mountains Oceans Giants An Epic of the 27th Century Translated by C D Godwin Volume One (contains Parts 1 and 2) I know of no attempt in literature that pulls together so boldly and directly the human and the divine, piling on every kind of action, thought, desire, love… Here perhaps the true face of “Expressionism” reveals itself for the first time. – Max Krell Originally published as Berge Meere und Giganten, S.Fischer Verlag, Berlin, 1924 This translation © C D Godwin 2019 This English translation of Alfred Döblin's Berge Meere und Giganten by C D Godwin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Based on the work at https://www.fischerverlage.de/buch/berge_meere_und_giganten/9783596904648 I hereby declare: I have translated this work by Alfred Döblin as a labour of love, out of a desire to bring this writer to wider attention in the English-speaking world. My approaches to UK and US publishing houses have borne no fruit; and so this work, first published in German more than 90 years ago, risks remaining unknown to readers of English. I therefore make it available as a free download from my website https://beyond-alexanderplatz.com under the above CC licence. I acknowledge the rights of S. Fischer Verlag as copyright holder of the source material. I have twice approached S Fischer Verlag regarding copyright permissions for my Döblin translations, but have received no answer; hence my adoption of the most restrictive version of the CC licence. C. D. Godwin 2018 Picture credits (Volume 1) Front cover: Detail from The Temptation of Saint Anthony, by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch. -

Zu Einem Formsemantischen Prinzip Bei Alfred Döblin

Resonantes Erzählen - Zu einem formsemantischen Prinzip bei Alfred Döblin The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Luemers, Arndt. 2016. Resonantes Erzählen - Zu einem formsemantischen Prinzip bei Alfred Döblin. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493436 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Resonantes Erzählen – Zu einem formsemantischen Prinzip bei Alfred Döblin A dissertation presented by Arndt Luemers to The Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Germanic Languages and Literatures Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Arndt Luemers All rights reserved. Prof. Judith Ryan, Prof. Oliver Simons Arndt Luemers Resonantes Erzählen – Zu einem formsemantischen Prinzip bei Alfred Döblin Abstract From the sympathetic vibration of strings to the resonance disasters of collapsing bridges, the physical phenomenon of resonance has fascinated people for centuries. In the 20th century, German writer Alfred Döblin takes up the notion of resonance in his philosophical text Unser Dasein. In Döblin’s understanding of the individual as an ‘open system,’ resonance features as the main natural principle that connects individuals with each other, but also with the world in general. This dissertation investigates the concept of resonance in its anthropological and literary implications for Döblin.