The Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unali'yi Lodge

Unali’Yi Lodge 236 Table of Contents Letter for Our Lodge Chief ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Letter from the Editor ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Local Parks and Camping ...................................................................................................................................... 9 James Island County Park ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Palmetto Island County Park ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Wannamaker County Park ............................................................................................................................................. 13 South Carolina State Parks ................................................................................................................................. 14 Aiken State Park ................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Andrew Jackson State Park ........................................................................................................................................... -

Monck's Corner, Berkeley County, South Carolina

Monck's Corner, Berkeley County, South Carolina by Maxwell Clayton Orvin, 1951 In Memoriam John Wesley Orvin, first Mayor of Moncks Corner, S.C., b. March 13, 1854, d. December 17, 1916.He was the son of John Riley Orvin, a Confederate States Soldier in Co. E., Fifth S.C. Cavalry and Salena Louise Huffman, South Carolina. Transcribed by D. Whitesell for South Carolina Genealogy Trails PREFACE The text of this little book is based on matter compiled for a general history of Berkeley County, and is presented in advance of that unfinished undertaking at the request of several persons interested in the early history of the county seat and its predecessor. Recorded in this volume are facts gleaned from newspaper articles, official documents, and hitherto unpublished data vouched for by persons of undoubted veracity. Newspapers might well be termed the backbone of history, but unfortunately few issues of newspapers published in Berkeley County between 1882 and 1936 can now be found, and there was a dearth of persons interested in ''sending pieces" to the daily papers outside the county. Thus much valuable information about the county at large and the county seat has been lost. A complete file of The Berkeley Democrat since 1936 has been preserved by Editor Herbert Hucks, for which he will undoubtedly receive the blessings of the historically minded. Pursuing the self-imposed task of compiling material for a history of the county, and for this volume, I contacted many people, both by letter and in person, and I sincerely appreciate the encouragement and help given me by practically every one consulted. -

Roy Acuff the Essential Roy Acuff (1936-1949) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Roy Acuff The Essential Roy Acuff (1936-1949) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: The Essential Roy Acuff (1936-1949) Country: US Released: 1992 Style: Country, Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1663 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1214 mb WMA version RAR size: 1779 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 496 Other Formats: MP1 APE AHX MIDI AIFF VOC WMA Tracklist Hide Credits Great Speckle Bird 1 2:56 Written-By – Roy Acuff, Roy Carter Steel Guitar Blues 2 2:52 Written-By – Roy Acuff Just To Ease My Worried Mind 3 2:39 Written-By – Roy Acuff Lonesome Old River Blues 4 2:49 Written-By – Traditional The Precious Jewel 5 2:46 Written-By – Roy Acuff It Won't Be Long (Till I'll Be Leaving) 6 3:01 Written-By – Roy Acuff Wreck On The Highway 7 2:48 Written-By – Dorsey Dixon Fireball Mail 8 2:34 Written-By – Floyd Jenkins Night Train To Memphis 9 2:51 Written-By – Beasley Smith, Marvin Hughes, Owen Bradley The Prodigal Son 10 2:48 Written-By – Floyd Jenkins Not A Word From Home 11 2:27 Written-By – Roy Acuff I'll Forgive You, But I Won't Forget You 12 2:41 Written-By – Joe L. Frank*, Pee Wee King Freight Train Blues 13 3:06 Written-By – Traditional Wabash Cannon Ball 14 2:37 Written-By – A. P. Carter Jole Blon 15 3:13 Written-By – Roy Acuff This World Can't Stand Long 16 2:42 Written-By – Roy Acuff Waltz Of The Wind 17 2:38 Written-By – Fred Rose A Sinners Death (I'm Dying) 18 2:41 Written-By – Roy Acuff Tennessee Waltz 19 2:53 Written-By – Pee Wee King, Redd Stewart Black Mountain Rag 20 2:51 Written-By – Tommy Magness Companies, etc. -

Ferguson on Huber, 'Linthead Stomp: the Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South'

H-Southern-Music Ferguson on Huber, 'Linthead Stomp: The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South' Review published on Friday, November 13, 2009 Patrick Huber. Linthead Stomp: The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. 440 pp. $30.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8078-3225-7. Reviewed by Robert H. FergusonPublished on H-Southern-Music (November, 2009) Commissioned by Christopher J. Scott Contextualizing Early Country Music and Modernity Since 1968, when country music historian Bill C. Malone publishedCountry Music U.S.A. to an initially incredulous academic audience, historians have come to view the study of country music, and its predecessors and offshoots, as intrinsically valuable. College catalogues routinely offer courses that incorporate country music, while social, cultural, and labor historians often deploy country song lyrics as primary documents. Historians, though, are frequently the last of the academic ilk to sense a new trend of study. But Malone, with the guidance and “tolerance” of his dissertation advisor, saw the merit in viewing country music as cultural markers for the lives and experiences of poor white Americans, a population often ignored by the historic record.[1] Malone and the late folklorist Archie Green, who published his influential article on hillbilly music only three years prior to Malone’s Country Music U.S.A., remain the earliest and most influential scholars of country and hillbilly music.[2] In Linthead Stomp, it is fitting that Patrick Huber draws heavily from the disciplines of both history and folklore to weave a compelling study of commercial hillbilly music and the Piedmont millhands who made up the majority of the musicians on record. -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

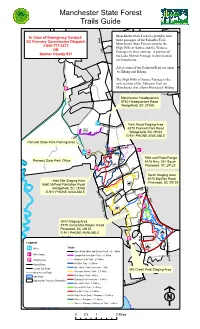

Manchester State Forest Trails Guide

Manchester State Forest Trails Guide d R H Manchester State Forest is proud to host in In Case of Emergency Contact: w G y three passt ages of the Palmetto Trail. n SC Forestry Commission Dispatch r Manchestu er State Forest contains the 1-800-777-3473 B 2 High Hills of Santee and the Wateree 6 OR 1 Passages in their entirety. A portion of Sumter County 911 the Lake Marion Passage is also located d on EMmainl Rchester. S p o ts R All sectionsd of the PalmettoTrail are open to Hiking and Biking. The High Hills of Santee Passage is the only section of the Palmetto Trail on !i Manchester that allows Horseback Riding. Manchester Headquarters 6740 Headquarters Road Wedgefield, SC 29168 !@Hea Park Road Staging Area dquar ad ters Ro 6370 Poinsett Park Road d !G a Wedgefield, SC 29168 o R E-911 PHONE AVAILABLE r Poinsett State Park Parking Area e v i R k Road !i t Par et !© !i ns !@ oi P Rifle and Pistol Range Poinsett State Park Office 5415 Hwy. 261 South d R !G ill Pinewood, SC 29125 s M d !i ma R rist Ch ek Cre rth South Staging Area Ea rs 6070 Big Bay Road Hart Site Staging Area lle u Pinewood, SC 29125 5580 Millford Plantation Road F !È H Wedgefield, SC 29168 w ad d. M o il R y i R ra E-911 PHONE AVAILABLE lf rd o ke ua r a G d L !i 2 w 6 P o D 1 l a n t a t i !i o !È n R d d OHV Staging Area R n i 5775 Camp Mac Boykin Road k y Pinewood, SC 29125 o E-911 PHONE AVAILABLE B !L c a !i M C Legend p o n m n a e Trails C !L !@ Office c t Open Road (Bike and Equine Trail) - 11.1 Miles o r !© Rifle Range R Campbell's Pond Bike Trail - 3.1 Miles -

Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2013 Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J. McCall East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McCall, Ronald J., "Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1121. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1121 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move __________________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ___________________________ by Ronald J. McCall May 2013 ________________________ Dr. Steven N. Nash, Chair Dr. Tom D. Lee Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Keywords: Family History, Southern Plain Folk, Herder, Mississippi Territory ABSTRACT Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move by Ronald J. McCall This thesis explores the settlement of the Mississippi Territory through the eyes of John Hailes, a Southern yeoman farmer, from 1813 until his death in 1859. This is a family history. As such, the goal of this paper is to reconstruct John’s life to better understand who he was, why he left South Carolina, how he made a living in Mississippi, and to determine a degree of upward mobility. -

The Charlotte Country Music Story

CHARLOTTE COUNTRY MUSIC STORY J3XQ, stfBT :. Yoaw Gel -Ve Wrapped Around Yopr finger 't !'.' I VWW* ««*». U-~~ fl'-u"". jj |ftl "=*£: '»*!&, <*v<H> Presented by North Carolina Arts Council Folklife Section Spirit Square Arts Center Charlotte, NC October 25, 26,1985 A-lS President of the Board of Directors of Charlotte's community center for the arts, it is particularly exciting to host The Charlotte Country Music Story. In addition to marvelous entertainment, Tfie Charlotte Country Music Story will preserve a part of this region's cultural heritage and recognize many of the artists whose pioneering work here in this community led to the formation of country music. I am grateful to the many individuals and organizations named elsewhere in this book whose effort made The Charlotte Country Music Story possible. I especially wish to thank the Folklife Section of the North Carolina Arts Council for serving as the coordinator of the project. Sincerely, y Roberto J. Suarez, President Board of Directors THE CHARLOTTE The Charlotte Country Music Story is the culmination of many months of research and COUNTRY MUSIC planning directed by the Folklife Section of the North Carolina Arts Council in partnership STORY with the Spirit Square Arts Center of Charlotte. It represents a novel collaboration between a state and a local cultural agency to recover a vital piece of North Carolina's cultural George Holt is director of the history. Too often we fail to appreciate the value of cultural resources that exist close at Folk-life Section of the North hand; frequently, it takes an outside stimulus to enable us to regard our own heritage with Carolina Arts Council and appropriate objectivity and pride. -

Townsend, Ph.D

THE BAPTIST HISTORY COLLECTION STATE HISTORIES SOUTH CAROLINA BAPTISTS 1670-1805 by Leah Townsend, Ph.D.. Thou hast given a standard to them that fear thee; that it may be displayed because of the truth — Psalm 60:4 The Baptist Standard Bearer, Inc. Version 1.0 © 2005 SOUTH CAROLINA BAPTISTS 1670-1805 BY LEAH TOWNSEND, PH.D. TO THE BAPTIST MINISTERS AND CHURCH CLERKS OF SOUTH CAROLINA whose cooperation has made this publication possible. Originally Published Florence, South Carolina 1935 CONTENTS FOREWORD 1. BAPTIST CHURCHES OF THE LOW-COUNTRY 2. BAPTIST CHURCHES OF THE PEEDEE SECTION 3. CHARLESTON ASSOCIATION OF BAPTIST CHURCHES 4. EARLY BAPTIST CHURCHES OF THE BACK COUNTRY 5. POST-REVOLUTIONARY REVIVAL 6. BACK COUNTRY ASSOCIATIONS 7. SIGNIFICANCE OF SOUTH CAROLINA BAPTISTS BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX MAP Baptist Churches in South Carolina prior to 1805, with location and date of construction. Compiled by Leah Townsend, drawn by E. Lamar Holman. ABBREVIATIONS CB — Church Book CC — Clerk of Court JC — Journal of the Council JCHA — Journal of the Commons House of Assembly JHR — Journal of the House of Representatives JS — Journal of the Senate PC — Probate Court RMC — Register of Mesne Conveyance SCHGM — South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine YBC — Year Book of the City of Charleston FOREWORD The manuscript of South Carolina Baptists 1670-1805 was submitted in 1926 to the Department of History of the University of South Carolina and accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy in American history. The undertaking grew out of the writer’s intense interest in religious history and the absence of any general account of the Baptists of this State; the effort throughout has been to treat Baptist history alone, and to give only enough political and religious background to present a clear view of the Baptists themselves. -

N Orth Carolina

56.11"17� Spring-Summ-------------er 2009 North Carolina � 0I t C 0 - (ti � 0 Ca fl North Carolina Folklore Journal Philip E. (Ted) Coyle, Editor Thomas McGowan, Production Editor The North Carolina Folklore Journal is published twice a year by the North Carolina Folklore Society with assistance from Western Carolina University, Ap palachian State University, and a grant from the North Carolina Arts Council, an agency funded by the State of North Carolina and the National Endowment for the Arts. Editorial AdvisoryBoard (2006-2009) Barbara Duncan, Museum of the Cherokee Indian Alan Jabbour, American Folklife Center (retired) Erica Abrams Locklear, University of North Carolina at Asheville Thomas McGowan, Appalachian State University Carmine Prioli, North Carolina State University Kim Turnage, Lenoir Community College The North Carolina Folklore Journalpublishes studies of North Carolina folk lore and folklife, analyses of folklore in Southern literature, and articles whose rigorous or innovative approach pertains to local folklife study. Manuscripts should conformto The MLAStyle Manual. Quotations from oral narrativesshould be transcriptions of spoken texts and should be identified by informant, place, and date. For information regarding submissions, view our website (http:/ paws.wcu.edu/ncfj), or contact: Dr. Philip E. Coyle Department of Anthropology and Sociology Western Carolina University Cullowhee, NC 28723 North Carolina Folklore Society2009 Offlcers Barbara Lau, President Allyn Meredith, 1st Vice President Shelia Wilson, 2nd Vice President Katherine R. Roberts, 3rd Vice President Christine Carlson Whittington, Secretary Janet Hoshour, Treasurer North Carolina Folklore Society memberships are $20 per year for individuals; student memberships are $15. Annual institutional and overseas memberships are $25. -

Archaeological Survey of the Proposed Santee Cooper Dalzell to Scottsville Transmission Line

AJRCJHIAJEOILOGIICAJL §1IJJRVJEY OIF 'II'IHIJE lPJROJPO§lElDl §AN'II'IEIE COOJPIEJR lDlAJLZIEILIL 11'0 §CO'II''II'§VIIJLILIE 'II'JRAN§MJI§§IION ILIINIE CHICORA IRESEARCJH[ CON'fRHBUl'HON 209 - - . - ------ - ~ - © 2001 by Chicora Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or transcribed in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior permission of Chicora Foundation, Inc., except for brief quotations used in reviews. Full credit must be given to the authors, publisher, and project manager. ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE PROPOSED SANTEE COOPER DALZELL TO SCOTTSVILLE TRANSMISSION LINE Prepared By: Michael Trinkley, Ph.D. with contributions by: Rachel Brinson-Marrs Prepared For: Mr. Ken Smoak Sabine and Waters PO Box 1072 Su=erville, SC 29483 Chicora Foundation Research Series 209 Chicora Foundation, Inc. PO Box 8664 • 861 Arbutus Drive Columbia, South Carolina 29202-8664 803/787-6910 Email: [email protected] March 7, 1997 This report is printed on permanent paper oo AIBS1'1RAC1' This study reports on an intensive inclusion on the National Register. Site 38SU38 is archaeological survey of the 19 mile long proposed a dense scatter of prehistoric remains on the sandy Dalzell-Scottsville 230-69 kV transmission line bluff overlooking the Black River, site 38SU270 is corridor for Santee Cooper. TI1is route runs fron1 the ren1ains of an antebellum plantation, and site the Mayesville 230 kV bay in the Gaillard 38SU272 is an African-American cemetery. For Crossroad vicinity southeastwardly through the these sites, green spacing (avoidance) or data Ardis Pond region and through Lee Swamp to the recovery IS necessary. -

Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination

Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hamilton, John C. 2013. Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11125122 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination A dissertation presented by Jack Hamilton to The Committee on Higher Degrees in American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2013 © 2013 Jack Hamilton All rights reserved. Professor Werner Sollors Jack Hamilton Professor Carol J. Oja Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination Abstract This dissertation explores the interplay of popular music and racial thought in the 1960s, and asks how, when, and why rock and roll music “became white.” By Jimi Hendrix’s death in 1970 the idea of a black man playing electric lead guitar was considered literally remarkable in ways it had not been for Chuck Berry only ten years earlier: employing an interdisciplinary combination of archival research, musical analysis, and critical race theory, this project explains how this happened, and in doing so tells two stories simultaneously.