Policy Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study (CCTS)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The consultants are grateful to Tmt. Susan Mathew, I.A.S., Addl. Chief Secretary to Govt. & Vice-Chairperson, CMDA and Thiru Dayanand Kataria, I.A.S., Member - Secretary, CMDA for the valuable support and encouragement extended to the Study. Our thanks are also due to the former Vice-Chairman, Thiru T.R. Srinivasan, I.A.S., (Retd.) and former Member-Secretary Thiru Md. Nasimuddin, I.A.S. for having given an opportunity to undertake the Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study. The consultants also thank Thiru.Vikram Kapur, I.A.S. for the guidance and encouragement given in taking the Study forward. We place our record of sincere gratitude to the Project Management Unit of TNUDP-III in CMDA, comprising Thiru K. Kumar, Chief Planner, Thiru M. Sivashanmugam, Senior Planner, & Tmt. R. Meena, Assistant Planner for their unstinted and valuable contribution throughout the assignment. We thank Thiru C. Palanivelu, Member-Chief Planner for the guidance and support extended. The comments and suggestions of the World Bank on the stage reports are duly acknowledged. The consultants are thankful to the Steering Committee comprising the Secretaries to Govt., and Heads of Departments concerned with urban transport, chaired by Vice- Chairperson, CMDA and the Technical Committee chaired by the Chief Planner, CMDA and represented by Department of Highways, Southern Railways, Metropolitan Transport Corporation, Chennai Municipal Corporation, Chennai Port Trust, Chennai Traffic Police, Chennai Sub-urban Police, Commissionerate of Municipal Administration, IIT-Madras and the representatives of NGOs. The consultants place on record the support and cooperation extended by the officers and staff of CMDA and various project implementing organizations and the residents of Chennai, without whom the study would not have been successful. -

18R Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

18R bus time schedule & line map 18R Broadway - Nanganallur View In Website Mode The 18R bus line (Broadway - Nanganallur) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Broadway: 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM (2) Cement Road: 1:00 PM - 10:25 PM (3) Cement Road: 1:40 PM (4) Nanganallur: 6:25 AM - 9:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 18R bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 18R bus arriving. Direction: Broadway 18R bus Time Schedule 32 stops Broadway Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Monday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Nanganallur Tuesday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Nanganallur Mgr Road MGR Road, Chennai Wednesday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Vetri Vel Thursday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Friday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Roja Medicals Bus Stop Saturday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Chidambaram Stores Market Road Bus Stop Pazavanthangal Road Junction 18R bus Info Direction: Broadway Junction Of Palavanthangal & GST Stops: 32 Trip Duration: 44 min Alandur Cement Road Line Summary: Nanganallur, Nanganallur Mgr Road, Vetri Vel, Roja Medicals Bus Stop, Chidambaram Stores, Market Road Bus Stop, Pazavanthangal Alandur Depot Road Junction, Junction Of Palavanthangal & GST, Alandur Cement Road, Alandur Depot, Ota Metro Ota Metro Station Station, Cantonment Board (St. Thomas Mount Head Post O∆ce), Prnaipalai / Alandur, Guindy R.S, Cantonment Board (St. Thomas Mount Head Chellammal College, Panagal Maligai, Saidapet, Raja Post O∆ce) Hostel, S.H.B., Nandanam Military Quarters, Vanavali, D.M.S.Metro Station, Gemini, Anand Prnaipalai / Alandur Theatre, Spensor Plaza (Tvs), LIC, Mount Road Post O∆ce, Shanthi Theatre, Simpsons / Periyar Bridge, Guindy R.S Pallavan Salai/Periyar Bridge, Central R.S. -

52K Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

52K bus time schedule & line map 52K Broadway - Saidapet View In Website Mode The 52K bus line (Broadway - Saidapet) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Broadway: 1:20 PM (2) Saidapet: 12:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 52K bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 52K bus arriving. Direction: Broadway 52K bus Time Schedule 34 stops Broadway Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 1:20 PM Monday 1:20 PM Saidapet Tuesday 1:20 PM Saidapet (Teachers Training College) Wednesday 1:20 PM Thadandar Nagar-Saidapet Thursday 1:20 PM Thadandar Nagar Friday 1:20 PM Raja Hostel Saturday 1:20 PM Nandanam S.H.B. 52K bus Info Nandanam Military Quarters Direction: Broadway Stops: 34 Trip Duration: 29 min Siet Line Summary: Saidapet, Saidapet (Teachers Training College), Thadandar Nagar-Saidapet, Vanavali Thadandar Nagar, Raja Hostel, Nandanam, S.H.B., Nandanam Military Quarters, Siet, Vanavali, Teynampet Teynampet, D.M.S.Metro Station, Gemini, Thousand Anna Salai Bus Lane, Chennai Light, Anand Theatre, T.V.S, Spensor Plaza (Tvs), LIC, LIC, L.I.C, Mount Road Post O∆ce, Shanthi Theatre, D.M.S.Metro Station The Hindu, P.Or & Sons, Simpsons / Periyar Bridge, Pallavan Salai/Periyar Bridge, Central R.S. Gemini (M.G.R.Central), Central Railway Station, Cls, Anna Flyover, Chennai Payaigada, Flower Market, Broadway, Parrys Corner, Broadway Thousand Light Aziz Muluk 7th Street, Chennai Anand Theatre Anna Salai (Mount Road), Chennai T.V.S Spensor Plaza (Tvs) LIC Anna Salai (Mount Road), Chennai LIC L.I.C 2 Boodha Perumal Street, Chennai Mount Road Post O∆ce Shanthi Theatre The Hindu Anna Statue Sub-Way, Chennai P.Or & Sons Simpsons / Periyar Bridge Pallavan Salai/Periyar Bridge Central R.S. -

Kamarajar Port Limited

December 15, 2017 Kamarajar Port Limited Summary of rated instruments Instrument Amount Rating Action Rs Crore Long Term; Tax Free Bonds 500.0 [ICRA]AA (Positive); reaffirmed *Instrument Details are provided in Annexure I Rating Action ICRA has reaffirmed the long term rating of [ICRA]AA (pronounced as ICRA double A) on the Rs 500 crore1 tax free bond issue of Kamarajar Port Limited (KPL / erstwhile Ennore Port Limited)2. The outlook on the long term rating is Positive. Rationale The rating reaffirmation takes into consideration the strong business profile of KPL; KPL’s status as the first corporatized port, which gives it greater autonomy to decide financial and administrative matters; and the flexibility to determine its tariff levels as it does not fall under the purview of the Tariff Authority for Major Ports (TAMP). The rating also considers the stable revenue streams of the company in the form of revenue shares from build-operate-transfer (BOT) concessionaires and the captive coal handling arrangement with TANGEDCO. The rating also factors in the comfortable financial profile characterized by healthy profitability, low gearing levels and strong debt coverage metrics; and the company’s favorable ownership pattern, with Government of India (GoI) holding 66.7% stake and Chennai Port (ChPT) holding 33.3% stake. The rating is however constrained by the large planned capital expenditure outlay towards development of new terminals, capital dredging and connectivity projects, which will have a long payback period and hence will impact the company’s return on capital employed in the medium term. The rating also considers the connectivity issues, with significant congestion on the roads from Ennore Port to its immediate hinterland and the delays in implementation of new connectivity projects which could impact the future growth of cargo volumes at the port. -

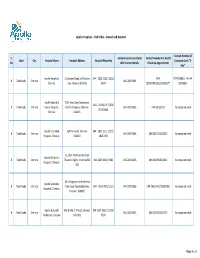

Chennai North Commissionerate Jurisdiction

Chennai North Commissionerate Jurisdiction The jurisdiction of Chennai North Commissionerate will cover the areas covering Chennai Corporation Zone Nos. I to IX (From Ward Nos. I to 126 in existence as on OL-O4-2OL7) in the State of Tamil Nadu. The Continental shelf and exclusive economic zone contiguous to the eastern coast of India. No.26l1, Mahathma Gandhi Road, Nungambakkam, Location Chennai 600 O34 Divisions under the jurisdiction of Chennai North Commissionerate. Sl.No. Divisions 1, Thiruvottiyur Division 2. Madhavaram Division 3. Royapuram Division 4. Parrys Division 5. Egmore Division 6. Thiru Vi Ka Nagar Division 7. Ambattur Division 8. Anna Nagar Division 9. Pursawalkam Division 10. Nungambakkam Division 11. Triplicane Division L2. Mylapore Division Page 5 of 83 l.Thiruvottirnrr Division of Chennai North Commissionerate Location Ananda Complex, 459, Anna Salai, Te5rnampet, Chennai - 600 018 Jurisdiction Areas covering Ward Nos. 1 to L4 of Zone I & Ward Nos. 15 to 2Iof Zone II of Chennai Corporation, Taxpayers names starting with letters A, B, Y and Z of the Continental shelf and exclusive economic zone contiguous to the eastern course of India. The Division has five Ranges with jurisdiction as follows: Name of the Range Location Jurisdiction Areas covering ward Nos. L to 4 of Zone I, Taxpayers names starting with letters A of the Range I Continental shelf and exclusive econornic zone contiguous to the eastern course of India. Areas covering ward Nos. 5 to 9 of Zone I, Range II Taxpayers names starting with letters B of the Ananda Continental shelf and exclusive econornic zone Complex, contiguous to the eastern course of India. -

Oil Spill Kamarajar Port Chennai Madras High Court Judgement.Pdf

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MADRAS DATED: 12/4/2018 C O R A M THE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE S.MANIKUMAR AND THE HON'BLE MRS.JUSTICE V.BHAVANI SUBBAROYAN Writ Petition No.8249 of 2018 Meenava Thanthai K.R.Selvaraj Kumar Meenavar Nala Sangam rep. By its President Mr.M.R.Thiyagarajan Having Office at No.48 East Madha Church Street Royapuram Chennai 600 013. ... Petitioner Vs 1. The Secretary to Government Union of India Ministry of Shipping Transport Bhavan New Delhi 110 001. 2. The State of Tamil Nadu rep. By its Secretary to Government Fisheries Department Fort St. George Chennai 600 009. 3. The District Collector Thiruvallur District. Thiruvallur. http://www.judis.nic.in 2 4. The District Collector Singaravelar Malligai Rajaji Salai Chennai 600 001. 5. The District Collector Kancheepuram District. 6. M/s. Kamarajar Port Limited rep. By its Chairman 4th Floor, Super Specialty Diabetic Centre (Erstwhile DLB Building) Rajaji Salai Chennai 600 001. 7. MT DAWN Kanchipuram Arya Voyagers Private Limited rep. By its Managing Director No.15 B Chandermukhi Building Narman Point Mumbai 400 021. 8. MT B.W.Maple M/s. Interocean Shipping I P Limited (Local agent for M/s. BW Maple) 3 Jafar Syrang Street Chennai 600 001. 9. The Director of Fisheries 485, 5th floor MTB Building Anna Salai Anna Colony Nandanam Chennai. ... Respondents Writ Petition filed under Article 226 of the Constitution of India, praying for issuance of a Writ of mandamus to direct the second respondent to pay the compensation to the persons affected by oil spillage happened on 28/1/2017 due to collide of ships M.T.DAWN http://www.judis.nic.inKanchipuram and MT BW Maple near Kamarajar Port, Chennai. -

ARM/E-AUCTION/ENRICH - 216 Date: 02/03/2020

(A GOVERNMENT OF INDIA UNDERTAKING) ASSET RECOVERY MANAGEMENT BRANCH Ref: ARM/E-AUCTION/ENRICH - 216 Date: 02/03/2020 To a. M/s.Enrich Tech Store, Rep. by its Partners Mrs.A.Rajalakshmi, Mr.S.T.Madhavan, Mrs.Mydeen Bi.A and Mr.Y.F.John Yesudhas Shop No.39, Plaza Centre No.129, G.N.Chetty Road, Nungambakkam, Chennai – 600034 Earlier at, M/s.Enrich Tech Store, No.42, Gee Gee Complex, Anna Salai Mount Road, Chennai – 600002 b. Mrs.A.Rajalakshmi, W/o.Mr.Anbazhagan, No.2, Thirumurugan Nagar, Kolathur, Chennai – 600099 c. Mr.S.T.Madhavan, S/o.S T L Narasimhan, M11, B Block, Y S Enclave, 134, Arcot Road, Virugambakkam, Chennai – 600092 d. Mrs.Mydeen Bi.A W/o.Anver Ali Sait, No.35/16, Muthamman Nagar, Ayanavaram, Chennai – 600023 e. Shri.Johan Yesudhas, S/o.Mr.Y.Vargheese, No.15, Safari Bhagawathy Flats, SIP Colony, Easwara Koil 2nd Street, Nanganallur, Chennai – 600061 2nd FLOOR, CIRCLE OFFICE BUILDING, 563/1 ANNA SALAI, TEYNAMPET, CHENNAI 600 018 Tel.No.2433 9160, 2435 0042. E-MAIL:[email protected] Website: www.canarabank.com 1 Madam / Dear Sir, Sub: Notice under Section 13(4) of the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 read with Rule 8(6) of the Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules, 2002 As you are aware, Canara Bank, Asset Recovery Management Branch had taken possession of the assets described in the Sale Notice annexed hereto in terms of Section 13(4) of the subject Act in connection with outstanding dues payable by you to our Asset Recovery Management Branch of Canara Bank. -

Apollo Hospitals - PAN India - Owned and Network

Apollo Hospitals - PAN India - Owned and Network Contact Number Of S. Ambulance Services Status Contact Number For Health State City Hospital Name Hospital Address Hospital Phone No Corporate Desk "If No With Contact Details Check-Up Appointment Any" Apollo Hospitals, 21,Greams Road, off.Greams 044 - 2829 0200 / 3333/ 044- 7299950882/ +91-44- 1 Tamilnadu Chennai 044-28291066 Chennai lane, Chennai-600006 3524 28290200/3333/28296577 28296012 Apollo Specialty 320, Anna Salai,Nandanam, 044 - 24336119 / 2436 2 Tamilnadu Chennai Cancer Hospital, Padma Complex, Chennai- 044-28291066 044-33151191 No corporate desk 3572/3646 Chennai 600035 Apollo First Med 154,P.H.Road, Chennai- 044 - 2821 1111 /2222/ 3 Tamilnadu Chennai 044-28291066 044-28211111/2222 No corporate desk Hospital, Chennai 600010 28237470 15, Shafi Mohammed Road, Apollo Children's 4 Tamilnadu Chennai Thousand Lights, Chennai 600 044-2829 6262/ 8283 044-28291066 044-28298282/6262 No corporate desk Hospital, Chennai 006 64, Vanagaram to Ambattur Apollo Speciality 5 Tamil Nadu Chennai main road, Ayanambakkam, 044 - 2653 7005/ 1021 044-28291066 044-26537060/30207060 No corporate desk Hospitals, Chennai Chennai - 600095 Apollo Hospitals 645 & 646, T H Road, Chennai 044-2591 3333 / 5533/ 6 Tamil Nadu Chennai 044-28291066 044-25913333/5533 No corporate desk Tondiarpet, Chennai 600 081 5599 {Page No. 1} Apollo Hospitals - PAN India - Owned and Network Contact Number Of S. Ambulance Services Status Contact Number For Health State City Hospital Name Hospital Address Hospital Phone No Corporate Desk "If No With Contact Details Check-Up Appointment Any" Apollo City Center, 134, Mint Street, Sowcarpet, 044-2529 6080/ 6082 / 7 Tamil Nadu Chennai 044-28291066 044-25296080/6082/6083 No corporate desk Chennai Chennai 600 079 6083/ 6084 Apollo Medical No.2 , OMR , Karappakkam, 8 Tamil Nadu Chennai 044- 24505700 044-24505700/30707777 No corporate desk Center, Chennai Chennai - 600097 Apollo Speciality 05/639, Old Mahabalipuram 044 - 33221111, Fax No. -

21 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

21 bus time schedule & line map 21 Broadway - Mandaveli View In Website Mode The 21 bus line (Broadway - Mandaveli) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Broadway: 4:45 AM - 11:20 PM (2) M.G.R Central: 12:42 AM (3) Mandaveli: 24 hours Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 21 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 21 bus arriving. Direction: Broadway 21 bus Time Schedule 34 stops Broadway Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 4:45 AM - 11:20 PM Monday 4:45 AM - 11:20 PM Mandaveli Tuesday 4:45 AM - 11:20 PM Mandaveli Market Wednesday 4:45 AM - 11:20 PM Ramakrishna Madam Thursday 4:45 AM - 11:20 PM RK Mutt Road, Chennai Friday 4:45 AM - 11:20 PM Mylapore Tank Saturday 4:45 AM - 11:20 PM LUZ Corner Luz Church Road, Chennai Amirtham Luz Church Road, Chennai 21 bus Info Direction: Broadway Valluvar Silai Stops: 34 Thiruvika Salai, Chennai Trip Duration: 27 min Line Summary: Mandaveli, Mandaveli Market, Y.M.I.A Ramakrishna Madam, Mylapore Tank, LUZ Corner, Thiruvika Salai, Chennai Amirtham, Valluvar Silai, Y.M.I.A, Ajantha, Hotel Swageth, Royapettah Police Station, Royapettah Ajantha General Hospital, Ymca Grounds Bus Stop, Wesley H.S., T.V.S, Anand Theatre, Anand Theatre, Thousand Hotel Swageth Lights Busstop, T.V.S, Spensor Plaza (Tvs), LIC, LIC, L.I.C, Mount Road Post O∆ce, Shanthi Theatre, The Royapettah Police Station Hindu, P.Or & Sons, Simpsons / Periyar Bridge, Sundareswara Koil Street, Chennai Pallavan Salai/Periyar Bridge, Central Railway Station, Cls, Payaigada, Flower Market, Broadway Royapettah General Hospital Society Road, Chennai Ymca Grounds Bus Stop Wesley H.S. -

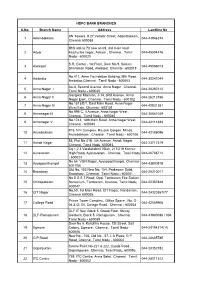

S.No. Branch Name Address Landline No 1 Adambakkam an Towers

HDFC BANK BRANCHES S.No. Branch Name Address Landline No AN Towers, # 27,Vellalar Street, Adambakkam, 1 Adambakkam 044-43846374 Chennai 600088 IRIS old no.70 new no 69, 3rd main road 2 Adyar kasthuriba nagar, Adayar , Chennai. Tamil 044-45504476 Nadu - 600020 S.R. Center , 1st Floor, Door No.9, Sriman 3 Alwarpet 044-45066013 Srinivasan Road, Alwarpet, Chennai - 600018 No.411, Amm Foundation Building, Mth Road, 4 Ambattur 044-30241044 Ambattur,Chennai. Tamil Nadu - 600053 Aa-8, Second Avenue, Anna Nagar , Chennai. 5 Anna Nagar I 044-26287412 Tamil Nadu - 600040 Gangwal Mansion, J-14, 3Rd Avenue, Anna 6 Anna Nagar II 044-26212456 Nagar East , Chennai. Tamil Nadu - 600102 No.1513/E/1, East Main Road, Anna Nagar 7 Anna Nagar IV 044-42831361 West Extn, Chennai - 600101 No.995-C, Ii Avenue, Anna Nagar West , 8 Annanagar III 044-30541049 Chennai. Tamil Nadu - 600040 No.1743, 18th Main Road, Anna Nagar West, 9 Annanagar V 044-42114388 Chennai - 600040 #15, N K Complex, Razack Gargen, Mmda, 10 Arumbakkam 044-42186096 Arumbakkam , Chennai. Tamil Nadu - 600106 53, Plot No 41B, 4th Avenue, Ashok Nagar, 11 Ashok Nagar 044-23717319 Chennai, Tamil Nadu, 600083. Cg 1,2,3 Varalakshmi Villah, 217/219 Konnur 12 Aynavaram High Road, Ayanavaram , Chennai. Tamil Nadu 044-26748712 - 600023 No 64, VGN Nagar, Ayyappanthangal, Chennai - 13 Ayyappanthangal 044-43800515 600 056. Old No, 153 New No, 154, Prakasam Salai, 14 Broadway 044-25210011 Broadway , Chennai. Tamil Nadu - 600001 No 5 G S T Road, Opp. Tambaram Fire Station, 15 Chitlapakkam Sanitorium, Tambaram, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, 044-22387848 600047. -

UCSC Counters

TACTV- ARASU E SEVAI CENTRE LOCATION DETAILS SL.NO. DISTRICT LOCATIONS ADDRESS 1 Chennai Aminjikarai No.4, West MadaStreet,Koyambedu,Aminjikarai,Chennai - 600 107 2 Chennai Ayanavaram No.25, United India Colony firstmain Road, Ayanavaram, Chennai-600 023 (Near AyanavaramMarket) 3 Chennai Egmore No.88, Mayor Ramanathan Salai, Chetpet,(NearPalimer Hotel) Chennai-600 034 4 Chennai Guindy No.370,Corporation Zone Office,Anna Salai, Richards Park,Saidapet, Chennai-15 5 Chennai Mambalam New No.1, Old No.2, Bharathidasan Salai, K.K.Nagar,. Chennai-600 078(Near R.T.O. office) 6 Chennai Mylapore No.28, PasumponMuthuramalingamSalai, Raja Annamalaipuram, Chennai-600 028 (Near Greenways Railway Station) 7 Chennai Perambur No.3, Perambur High Road,Near,Perambur Railway Station,Perambur, Chennai-600 011. 8 Chennai Purasawalkam No.3, Raja Muthaiah Salai (Old FortTondiarpet Taluk office),Purasaiwalkam, Chennai-600 003 9 Chennai Tondaiyarpet Corporation Community Centre,Door No. 473, Thiruvoittyur HighRoad, (Nearby to Appolo Hospital)Tondiarpet,Chennai-600081 10 Chennai Velacherry No.113, V.V.Koil Street,Institute of Road Transport Training centre complex,.Tharamani 100 feet Road,Chennai -600 113. 11 Chennai Secretariat Secretariat,Fort St George, Chennai-600009. 12 Chennai Corporation Head Office Corporation of Chennai/Rippon Building,Chennai 13 Chennai Zone 1-Thiruvotriyur No.945, Thiruvotriyur High Road, Chennai - 600019. 14 Chennai Zone 2 - Manali No.127, Padasalai Street, Manali , Chennai - 600 068. 15 Chennai Zone 3 - Madhavaram No.1,Thattankulam Street, Bazaar Road, Madhavaram, Chennai–600060 16 Chennai Zone 4 - Tondiarpet No.266, Thiruvotriyur High Road, Chennai – 600021. 17 Chennai Zone 5 -Royapuram No.62, Basin Bridge Road, Chennai– 600079. -

Chennai Based Companies

List Of Software Companies in Chennai Ashok Pillar / KK. Nagar / Kodambakkam 1. Wellwin Industries, 2. Marrs Software, 25,5th Floor, Sekar Towers, 25,First Main Road, United India Colony, 1st Main Road, United India Colony, Kodambakkam, Kodambakkam,Chennai-24. Chennai-24. 3. Vector Software, 4. Tulip Software 5/2,Kamarajar Street, Gandhi Nagar, 52nd Street, 7th Avenue, Saligramam, Chennai-600093. Ashok Nagar, Chennai 5. Spat Consultancy, 6. Softsolutions, 142,Avm Avenue, 8th Street, 1st Floor, C-19, 16th Avenue, Ashok Nagar, Chennai-92. Chennai-83. 7. Softeam Software, 8. Pictoria Entertainment, 52nd Street, 7th Avenue, Ashok Nagar, 4, 3rd Floor, Planna Plaza, 74,Arcot Road, Chennai. Chennai-24. 9. Pentafour Software Exports, 10.Intech Business Solutions, 1,First Main Road, 1st Floor, Sannadhi Street, Vadapalani, Kodambakkam, Chennai - 600 024 Chennai-26. 11. Ana Software Technologies, 12.Congurence Software Ltd., 53,1st Floor, Lakshmi Towers, Arcot Road, 2,Ramavaram Main Road, Chennai-600024. Ramavaram, Chennai. 13. HCL Peripherals, 14.Pyramid Business Systems, 158,Arcot Road, 52nd Street, 7th Avenue, Ashok Nagar, Vadapalani, Chennai-26. Chennai. 15.Icon Systems, 48,2nd Floor, Balaji Nagar, 1st Main, Ekkadu Thangal, Chennai-97. Adyar 2. DSM Soft (P) Ltd. 1. Computer International, 9, 15th Cross Street, Shastri Nagar, 152,Annai Velankanni Church Road, Adayar, Madras - 600 020 Vannanthurai, Besant Nagar, Chennai-90. Phone: 4913878, 4911376 Fax: 4910847 3. Manmar, 4. Naturesoft Creative Software Solutions, 55,L.B.Road, Thiruvanmiyur, 3,4th Main Road, Kotturpuram, Chennai-41. Chennai-85. 5. Oceania Software, 6. Open Business Solutions, 73,2nd Main Road, Gandhinagar, Adyar, Japasri, 39,4th Main Road, Gandhi Nagar, Chennai-20.