OSCE Yearbook 2005 Considers a Wealth of Current and Perennial Themes, by No Means All of Which Can Be Treated Adequately in a Short Fore- Word

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Stalin Revolutionary, Politician, Generalissimus and Dictator

Military Despatches Vol 34 April 2020 Flip-flop Generals that switch sides Surviving the Arctic convoys 93 year WWII veteran tells his story Joseph Stalin Revolutionary, politician, Generalissimus and dictator Aarthus Air Raid RAF Mosquitos destory Gestapo headquarters For the military enthusiast CONTENTS April 2020 Page 14 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and techno-speak that few Russian Special Forces outside the military could hope to under- stand. Some of the terms Features 34 were humorous, some A matter of survival were clever, while others 6 This month we continue with were downright crude. Ten generals that switched sides our look at fish and fishing for Imagine you’re a soldier heading survival. into battle under the leadership of Part of Hipe’s “On the a general who, until very recently 30 couch” series, this is an been trying very hard to kill you. interview with one of How much faith and trust would Ranks you have in a leader like that? This month we look at the author Herman Charles Army of the Republic of Viet- Bosman’s most famous 20 nam (ARVN), the South Viet- characters, Oom Schalk Social media - Soldier’s menace namese army. A taxi driver was shot Lourens. Hipe spent time in These days nearly everyone has dead in an ongoing Hanover Park, an area a smart phone, laptop or PC plagued with gang with access to the Internet and Quiz war between rival taxi to social media. -

Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia's Hybrid Foreign Policy—The Case of Ukraine

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 64 Number 1 Internationalism and Sovereignty Article 3 (Fall 2019) 4-23-2020 Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Foreign Policy—The Case of Ukraine. Igor Gretskiy [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Igor Gretskiy, Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Foreign Policy—The Case of Ukraine., 64 St. Louis U. L.J. (2020). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol64/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW LUKYANOV DOCTRINE: CONCEPTUAL ORIGINS OF RUSSIA’S HYBRID FOREIGN POLICY—THE CASE OF UKRAINE. IGOR GRETSKIY* Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kremlin’s assertiveness and unpredictability on the international arena has always provoked enormous attention to its foreign policy tools and tactics. Although there was no shortage of publications on topics related to different aspects of Moscow’s foreign policy varying from non-proliferation of nuclear weapons to soft power diplomacy, Russian studies as a discipline found itself deadlocked within the limited number of old dichotomies, (e.g., West/non-West, authoritarianism/democracy, Europe/non-Europe), initially proposed to understand the logic of Russia’s domestic and foreign policy transformations.1 Furthermore, as the decision- making process in Moscow was getting further from being transparent due to the increasingly centralized character of its political system, the emergence of new theoretical frameworks with greater explanatory power was an even more difficult task. -

The Diary of Anatoly S. Chernyaev 1986

The Diary of Anatoly S. Chernyaev 1986 Donated by A.S. Chernyaev to The National Security Archive Translated by Anna Melyakova Edited by Svetlana Savranskaya http://www.nsarchive.org Translation © The National Security Archive, 2007 The Diary of Anatoly S. Chernyaev, 1986 http://www.nsarchive.org January 1st, 1986. At the department1 everyone wished each other to celebrate the New Year 1987 “in the same positions.” And it is true, at the last session of the CC (Central Committee) Secretariat on December 30th, five people were replaced: heads of CC departments, obkom [Oblast Committee] secretaries, heads of executive committees. The Politizdat2 director Belyaev was confirmed as editor of Soviet Culture. [Yegor] Ligachev3 addressed him as one would address a person, who is getting promoted and entrusted with a very crucial position. He said something like this: we hope that you will make the newspaper truly an organ of the Central Committee, that you won’t squander your time on petty matters, but will carry out state and party policies... In other words, culture and its most important control lever were entrusted to a Stalinist pain-in-the neck dullard. What is that supposed to mean? Menshikov’s case is also shocking to me. It is clear that he is a bastard in general. I was never favorably disposed to him; he was tacked on [to our team] without my approval. I had to treat him roughly to make sure no extraterritoriality and privileges were allowed in relation to other consultants, and even in relation to me (which could have been done through [Vadim] Zagladin,4 with whom they are dear friends). -

Mikhail Gorbachev and His Role in the Peaceful Solution of the Cold War

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2011 Mikhail Gorbachev and His Role in the Peaceful Solution of the Cold War Natalia Zemtsova CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/49 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Mikhail Gorbachev and His Role in the Peaceful Solution of the Cold War Natalia Zemtsova May 2011 Master’s Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of International Affairs at the City College of New York Advisor: Jean Krasno ABSTRACT The role of a political leader has always been important for understanding both domestic and world politics. The most significant historical events are usually associated in our minds with the images of the people who were directly involved and who were in charge of the most crucial decisions at that particular moment in time. Thus, analyzing the American Civil War, we always mention the great role and the achievements of Abraham Lincoln as the president of the United States. We cannot forget about the actions of such charismatic leaders as Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin, Winston Churchill, and Franklin D. Roosevelt when we think about the brutal events and the outcome of the World War II. Or, for example, the Cuban Missile Crisis and its peaceful solution went down in history highlighting roles of John F. -

University of Copenhagen

Hvorfor gik Danmark i krig? Kosovo og Afghanistan Mariager, Rasmus Mølgaard; Wivel, Anders Publication date: 2019 Document version Også kaldet Forlagets PDF Citation for published version (APA): Mariager, R. M., & Wivel, A. (red.) (2019). Hvorfor gik Danmark i krig? Kosovo og Afghanistan. Download date: 09. apr.. 2020 HVORFOR GIK DANMARK I KRIG? Kosovo og Afghanistan Kosovo og Afghanistan 2 Redigeret af Rasmus Mariager og Anders Wivel Hvorfor gik Danmark i krig? Kosovo og Afghanistan Bind 2 Rasmus Mariager og Anders Wivel (red.) Forord Dette bind er skrevet af Mikkel Runge Olesen samt Sanne Aagaard Jensen og Jakob Linnet Schmidt. Olesen har skrevet fremstillingen ”Pest eller kolera. En analyse af beslutningsprocessen bag det danske militære engagement i Koso- vo 1998-1999”. Jensen og Schmidt har skrevet ”Med hele vejen. En analyse af beslutningsprocessen bag det danske militære engage- ment i Afghanistan i 2001”. Forskerne har haft uhindret adgang til relevant kildemateriale beroende i blandt andet Udenrigsministeriets, Statsministeriets, Forsvarsministeriets og Værnsfælles Forsvarskommandos arkiver. Desuden har forskerne indsamlet og anvendt et omfattende kil- demateriale af ikke-statslig proveniens, herunder har forskerne anvendt materiale fra privatarkiver og foretaget interviews med politikere og embedsmænd. For en oversigt over fremstillingernes materialegrundlag henvises til de enkelte analyser. Undersøgelserne udgør en del af grundlaget for udredningen Hvor- for gik Danmark i krig? Rasmus Mariager Anders Wivel Forskningsleder -

The EU Border Mission at Work Around Transdniestria: a Win-Win Case?

n°21, janvier 2010 Daria Isachenko Université Humboldt de Berlin & Université de Magdeburg The EU border mission at work around Transdniestria: a win-win case? Until recently little was known about Transdniestria, a small piece of territory situated between Moldova and Ukraine. What was mostly known is that this place is a “diplomatically isolated haven for transnational criminals and possibly terrorists”, a “black hole” making “weapons, ranging from cheap submachine guns to high-tech missile parts”.1 In brief, it is a “gunrunner’s haven”, where “just about every sort of weapon is available” upon request.2 Moreover, to arms production and smuggling, many experts add human trafficking and drug smuggling.3 Transdniestria as an informal state appeared on the scene in the early 1990s as the Soviet Union was on the verge of collapse. Since then, Transdniestria remains a contested territory which officially belongs to Moldova, but has managed to create its own attributes of statehood, seeking international recognition. The claim to statehood of this entity presents a great challenge to Moldova’s territorial integrity, whose officials mostly view this statelet as a puppet, created by the “certain circles” in the Kremlin with the sole purpose of keeping Moldova under Russia’s sphere of influence. Since no progress was made in settling this “frozen” conflict over the years, Moldova started to search for allies in the West. By 2005 the Moldovan government managed to persuade the European Union to 1 G. P. Herd, “Moldova and the Dniestr region: contested past, frozen present, speculative futures?”, Central and Eastern Europe Series, 05/07, Conflict Studies Research Centre, Defence Academy of the United Kingdom, Febuary 2005. -

Latvia 1988-2015: a Triumph of the Radical Nationalists

The Baltic Centre of Historical and Socially Political Studies Victor Gushchin Latvia 1988-2015: a triumph of the radical nationalists Political support of the West for Latvian radical nationalism and neo-Nazismand the import of this ideology into Latvia after the West’s victory in the Cold War. Formation of a unipolar world led by the USA, revision of the 1945 Yalta and Potsdam treaties and the 1975 Helsinki Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe as main reasons for the evolution of the Republic of Latvia of May 4th, 1990,from elimination of universal suffrage to relapse of totalitarianism: establishment of the so-called «Latvian Latvia», Russophobia, suppression of ethnic minority rights, restriction of freedom of speech and assembly, revision of the outcome of World War Two and propaganda of neo-Nazism. Riga 2017 UDK 94(474.3) “19/20” Gu 885 The book Latvia 1988-2015: a triumph of the radical nationalists» is dedicated to Latvia’s most recent history. On May 4, 1990, the Supreme Soviet (Supreme Council) of the Latvian SSR adopted the Declaration on the Restoration of Independence of the Latvian Republic without holding a national referendum, thus violating the acting Constitution. Following this up on October 15, 1991, the Supreme Soviet deprived more than a third of its own electorate Latvia 1988 - 2015: of the right to automatic citizenship. As a result, one of the most fundamental principles of a triumph of the radical nationalists democracy, universal suffrage, was eliminated. Thereafter, the Latvian parliament, periodically re-elected in conditions where a signif- icant part of country’s inhabitants lack the right to participate in elections, has been adopting Book 1. -

Chronology End of the Cold War in Europe

Chronology End of the Cold War in Europe (This chronology was compiled by the National Security Archive staff in April 1998 for the conference “The End of the Cold War in Europe, 1989: ‘New Thinking’ and New Evidence) 1987 January 12 - Jaruzelski meets with Pope John Paul II in Italy, Jaruzelski's first official visit to the West since the imposition of martial law in Poland. (Dawisha, p. 283, Foreign, p. 300) January 20 - The USSR stops jamming the BBC. (Garthoff, 304) January 21 - The CPSU Politburo discusses withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan. Foreign Minister Shevardnadze advocates only a partial withdrawal and massive support of the Najib regime. Prime Minister Nikolai Ryzhkov categorically demands a complete withdrawal. Gorbachev proposes "to pull it off within two years." (The Archive of Gorbachev Foundation) January 22 - The CPSU Politburo discusses "acceleration" in upgrading the machine- building industries. (The Archive of the Gorbachev Foundation) January 27 - At a meeting of the Central Committee Gorbachev surprises members with his description of the country as being one of "developing socialism," rather than the stock phrase, "developed socialism," and with approvals of "real elections" and secret ballots. This provides an opening wedge for the introduction of democratic procedure. (Matlock, 64; Garthoff, 303) January 29 - The CPSU Politburo holds discussions on the results of the Warsaw conference of CC secretaries of Comecon countries. The participants point at the growing pro-Western orientation of Eastern Europe. Anatoly Dobrynin argues against "over dramatizing the nuances in the behavior of Honecker." Gorbachev agrees that "they should remain friends." (The Archive of the Gorbachev Foundation) February 10 - The USSR announces that it has pardoned 140 prisoners convicted of subversive activities. -

The Transformation of Practices of Soviet Speechwriters from the Brezhnev Era to the Early Perestroika Period

Speechwriting als Beruf: The Transformation of Practices of Soviet Speechwriters from the Brezhnev Era to the Early Perestroika Period By Yana Kitaeva Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Supervisor: Alexander Astrov Second Reader: Marsha Siefert CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2019 Copyright Notice Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract The aim of this thesis is to offer a new perspective within the field of Soviet Subjectivity through the concept of the kollektiv proposed by Oleg Kharkhordin and applied to the case study of Soviet Secretary General‘s speechwriters from Brezhnev to Gorbachev. Namely, I examine the transformations in speechwriting practices of the kollektiv in the 1970s and 1980s. The kollektiv underwent a process of routinization in the early Brezhnev era, establishing a system of collective writing intended merely to transmit Party directives. This routine, which the contemporaries had described as numbing and uninspiring, had completely changed under Gorbachev. Practically, the routine of the speechwriting had become the continuous process of the creation of new ideas under the supervision of the Secretary General in the mid-1980s. -

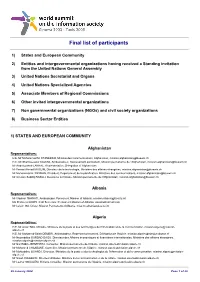

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

From Axis Surprises to Allied Victories from AFIO's the INTELLIGENCER

Association of Former Intelligence Officers From AFIO's The Intelligencer 7700 Leesburg Pike, Suite 324 Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies Falls Church, Virginia 22043 Web: www.afio.com, E-mail: [email protected] Volume 22 • Number 3 • $15 single copy price Winter 2016-17 ©2017, AFIO The Bleak Years: 1939 – Mid-1942 GUIDE TO THE STUDY OF INTELLIGENCE The Axis powers repeatedly surprised Poland, Britain, France, and others, who were often blinded by preconceptions and biases, in both a strategic and tactical sense. When war broke out on September 1, 1939, the Polish leadership, ignoring their own intelligence, lacked an appreciation of German mili- tary capabilities: their cavalry horses were no match From Axis Surprises to Allied for German Panzers. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain misread Hitler’s intentions, unwilling to Victories accept the evidence at hand. This was the consequence of the low priority given to British intelligence in the The Impact of Intelligence in World War II period between wars.3 Near the end of the “Phony War” (September 3, 1939 – May 10, 1940) in the West, the Germans engi- By Peter C. Oleson neered strategic, tactical, and technological surprises. The first came in Scandinavia in early April 1940. s governments declassify old files and schol- ars examine the details of World War II, it is Norway Aapparent that intelligence had an important The April 9 German invasion of Norway (and impact on many battles and the length and cost of this Denmark) was a strategic surprise for the Norwegians catastrophic conflict. As Nigel West noted, “[c]hanges and British. -

Winter 2018 | a Benefit of Membershipletter in the Museum of Danish America

americaWINTER 2018 | A BENEFIT OF MEMBERSHIPletter IN THE MUSEUM OF DANISH AMERICA How the events of 1918 shaped a Danish-American family. INSIDE More stories of war and peace contents ENDINGS14 & BEGINNINGS RESISTING23 IN WWII 32BIKING VIKINGS 38WARTIME MEMORIES 04 Director’s Corner 23 Occupation and 41 News in Brief Resistance 06 Survey Results 27 Exhibits 42 New Members and Old Friends 08 Nordic DC 28 Collection Connection 10-Year Interns 11 Events Calendar 30 CAP Program 46 12 Meeting in Elk Horn 32 Bicycle Tour 48 Holiday Craft 14 Across Oceans, 38 Wartime Tales Across Time, Across Generations ON THE COVER America Letter Winter 2018, No. 3 John and Meta Nielsen suff ered extraordinary Published three times annually by the Museum of Danish America hardships before fi nding each other and building 2212 Washington Street, Elk Horn, Iowa 51531 their family. Read about it, beginning on page 14. 712.764.7001, 800.759.9192, Fax 712.764.7002 danishmuseum.org | [email protected] 2 staff & interns Executive Director Building & Grounds Manager Administrative Assistant Rasmus Thøgersen, M.L.I.S. Tim Fredericksen Terri Amaral E: rasmus.thoegersen E: tim.fredericksen E: terri.amaral Administrative Manager Albert Ravenholt Curator of Genealogy Center Manager Terri Johnson Danish-American Culture Kara McKeever, M.F.A. E: terri.johnson Tova Brandt, M.A. E: kara.mckeever E: tova.brandt Development Manager Genealogy Assistant Deb Christensen Larsen Curator of Collections Wanda Sornson, M.S. E: deb.larsen & Registrar E: wanda.sornson Angela Stanford, M.A. Communications Specialist, E: angela.stanford Executive Director Emeritus America Letter Editor John Mark Nielsen, Ph.D.