2.1. Dancing the Poot! Devo and Postmodernism 1975 - 1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fro F M V M°J° Nixon Is Mojo Is in A

TW O G R EA T W H A T'S FILMS FROMI HAPPENING S O U TH T O VIC AFR ICA DUNLO P 9A 11A The Arts and Entertainment Section of the Daily Nexus OF NOTE THIS WEEK 1 1 « Saturday: Don Henley at the Santa Barbara County Bowl. 7 p.m. Sunday: The Jefferson Airplane re turns. S.B. County Bowl, 3 p.m. Tuesday: kd. long and the reclines, country music from Canada. 8 p.m. at the Ventura Theatre Wednesday: Eek-A-M ouse deliv ers fun reggae to the Pub. 8 p.m. Definately worth blowing off Countdown for. Tonight: "Gone With The Wind," The Classic is back at Campbell Hall, 7 p.m. Tickets: $3 w/student ID 961-2080 Tomorrow: The Second Animation -in n i Celebration, at the Victoria St. mmm Theatre until Oct. 8. Saturday: The Flight of the Eagle at Campbell Hall, 8 p.m. H i « » «MI HBfi MIRiM • ». frOf M v M°j° Nixon is Mojo is in a College of Creative Studies' Art vJVl 1T1.J the man your band with his Gallery: Thomas Nozkowski' paint ings. Ends Oct. 28. University Art Museum: The Tt l t f \ T/'\parents prayed partner, Skid Other Side of the Moon: the W orldof Adolf Wolfli until Nov. 5; Free. J y l U J \ J y ou'd never Roper, who Phone: 961-2951 Women's Center Gallery: Recent Works by Stephania Serena. Large grow up to be. plays the wash- color photgraphs that you must see to believe; Free. -

Subculture Magazine - Alternative Music and Culture Magazine

Subculture Magazine - alternative music and culture magazine. The ultimate ...c, darkwave, synthpop, alternative and post punk music. always on the edge. User Password Sign Up | Forgot Password Thursday, Dec 08 , 2005 Devo - Live 1980 (DVD) Posted :Thu, Dec 8th, 2005 00:20:24 Devo Devo - Live 1980 (DVD) Target Video Review By : Vivien Weimar With 80s nostalgia being de rigueur these days, the time is ripe for a DEVO reunion. The reclusive new wave band usually doesn't tour much as original founder Mark Mothersbaugh has since moved on to creating commercials and soundtracks at his Los Angeles production company Mutato Muzika (that fantastically weird space-ship-looking building on Sunset Boulevard) along with the other Devo members save Jerry Casale who has been directing videos for such bands as the Foo Fighters and Soundgarden. However, this summer Devo got together and played limited dates all across the country--and this fall they released Live 1980, a full-length concert video shot at the Phoenix Theatre in Petaluma, CA on August 17, 1980. Complete with white uniforms, blue background screen and "energy domes" (don't you dare call them flower-pot hats), Devo play the hits off of their albums, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We are Devo!, Duty Now For the Future and Freedom of Choice. Twenty-one songs are featured in this 75-minute disc including the classic MTV staple "Whip It", the oft-covered "Girl U Want", and their own covers of Johnny River's classic "Secret Agent Man" and the Rolling Stones "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction". -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

Rsd21 Drop 1 Remainders 4 July Customer Version

STOCK REMAINING FROM RSD21 DROP 1, JUNE 12, 2021 Items in bold are RSD Drop 1, everything else is back catalogue by the same artists THIS LIST UPDATED 4/7/21; MORE BACK CATALOGUE IN THE NEXT VERSION ITEM ARTIST TITLE FORMAT INFO PRICE £ 1. AC/DC Through The Mists Of Time/Witches Spell 12" clear vinyl Single Classic rock 20.99 2. AC/DC PWR/UP Ltd edn yellow vinyl LP Classic rock 34.99 (NOT RSD) 3. AIR People in the City 12" Picture Disc Electronic 22.75 4. AIR 10 000 H2 Legend 2LP Electronic 22.99 (NOT RSD) 5. ALARM, THE Spirit of '58 7" Punk 12.25 6. ALARM, THE Celtic Folklore Live in London and California 1988 LP Punk 22.99 (NOT RSD) 7. ALARM, THE Equals (2018) LP + poster Punk 18.99 (NOT RSD) 8. ALBERT COLLINS & Albert Collins & Barrelhouse Live 1LP transparent red / solid white / Rock 21.99 BARRELHOUSE black 9. AMORPHOUS ANDROGYNOUS, The World Is Full Of Plankton 10" Techno 14.99 THE 10. ANIMAL COLLECTIVE Prospect Hummer 12" EP Indie 25.49 11. ANTI-FLAG 20/20 Division 1 LP - Coloured Rock 26.25 12. ANTI-FLAG The Bright Lights of America 2LP green vinyl, this is #0462 Includes poster 21.99 (NOT RSD) 13. ANTI-FLAG The General Strike LP Rock 18.99 (NOT RSD) 14. ANTI-FLAG Live acoustic at 11th Street Records LP Rock WAS (RSD16) 20.99 NOW 16.80 15. ARNIE LOVE & THE LOVELETTS Invisible Wind 12" Soul 11.49 16. ART BLAKEY AND HIS JAZZ Chippin' In 2XLP with insert Jazz 39.49 MESSENGERS 17. -

Music History Lecture Notes Modern Rock 1960 - Today

Music History Lecture Notes Modern Rock 1960 - Today This presentation is intended for the use of current students in Mr. Duckworth’s Music History course as a study aid. Any other use is strictly forbidden. Copyright, Ryan Duckworth 2010 Images used for educational purposes under the TEACH Act (Technology, Education and Copyright Harmonization Act of 2002). All copyrights belong to their respective copyright holders, • Rock’s classic act The Beatles • 1957 John Lennon meets Paul McCartney, asks Paul to join his band - The Quarry Men • George Harrison joins at end of year - Johnny and the Moondogs The Beatles • New drummer Pete Best - The Silver Beetles • Ringo Star joins - The Beatles • June 6, 1962 - audition for producer George Martin • April 10, 1970 - McCartney announces the group has disbanded Beatles, Popularity and Drugs • Crowds would drown of the band at concerts • Dylan turned the Beatles on to marijuana • Lennon “discovers” acid when a friend spikes his drink • Drugs actively shaped their music – alcohol & speed - 1964 – marijuana - 1966 – acid - Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery tour – heroin in last years Beatles and the Recording Process • First studio band – used cutting-edge technology – recordings difficult or impossible to reproduce live • Use of over-dubbing • Gave credibility to rock albums (v. singles) • Incredible musical evolution – “no group changed so much in so short a time” - Campbell Four Phases of the Beatles • Beatlemania - 1962-1964 • Dylan inspired seriousness - 1965-1966 • Psychedelia - 1966-1967 • Return to roots - 1968-1970 Beatlemania • September 1962 – “Love me Do” • 1964 - “Ticket to Ride” • October 1963 – I Want To Hold your Hand • Best example • “Yesterday” written Jan. -

Extensions of Remarks E503 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

April 3, 2014 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E503 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS REMEMBERING BOB CASALE OF HONORING MR. NICHOLAS P. a $22 million 125,000 square foot campus in DEVO DINAPOLI Westminster, Colorado, creating an additional 100 high paying jobs. HON. STEVE ISRAEL I extend my deepest congratulations to Trimble Navigation for receiving the Business HON. TIM RYAN OF NEW YORK Recognition Award from the Jefferson County OF OHIO IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Economic Development Corporation. I thank IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Thursday, April 3, 2014 you for your commitment to innovation, high standards and quality products. Thursday, April 3, 2014 Mr. ISRAEL. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to honor Mr. Nicholas P. DiNapoli, an esteemed f Mr. RYAN of Ohio. Mr. Speaker, I rise today citizen of my congressional district who holds NATIONAL SCHOOL LUNCH to honor the remarkable life of Bob Casale, the distinction of being a lifelong resident of PROGRAM who passed away on February 17, 2014, at the Town of North Hempstead. Mr. DiNapoli the age of sixty-one. Bob was raised in Akron, was born on April 6, 1924, to Pete and Jea- HON. TED POE nette DiNapoli in Roslyn Heights, New York, Ohio. He led an exemplary life while in pursuit OF TEXAS of his dream of writing, producing, and per- and has resided in Albertson, New York since IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES forming music. Bob helped create a body of 1953. He is a New Yorker, born and bred. Thursday, April 3, 2014 work with his band Devo that put the ‘‘new’’ in After graduating from Roslyn public schools, new wave music. -

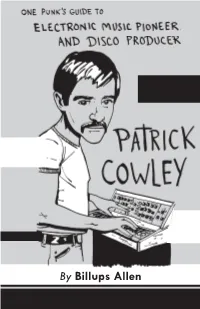

By Billups Allen Billups Allen Is a Record Store Clerk Who Spent His Formative Years in and Around the Washington D.C

By Billups Allen Billups Allen is a record store clerk who spent his formative years in and around the Washington D.C. punk scene. He graduated from the University of Arizona with a creative writing major and film minor. He currently lives in Memphis, Tennessee where he publishes Cramhole zine, contributes regularly to Razorcake, Lunchmeat, and Ugly Things, and writes fiction (cramholezine.com, billupsallen@ gmail.com) Illustrations by Danny Martin: Zines, murals , stickers, woodcuts, and teachin’ screen printing at a community college on the side. (@DannyMartinArt) Zine design by Todd Taylor Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. One Punk’s Guide to Patrick Cowley originally appeared in Razorcake #107, released in December 2018/January 2019. This zine is made possible in part by support by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles Arts Commission. Printing Courtesy of Razorcake Press razorcake.org n 1978 a DJ subscription-only remix of the already popular Donna Summer song “I Feel Love” went out in the mail. It was 15:43 long. The bass line was looped so overdubbed synthesizer effects could be added. This particular version of the song went largely unnoticed by the general public and did nothing to make producer Patrick Cowley a household name. But dancers in nightclubs reacted. They may have been unaware and/or unconcerned about what they were hearing, but they reacted. -

Thesis Writing Deliverables (Pdf)

DEFENSE SPEECH Discovering and listening to music has always been my biggest passion in life and my primary way of coping with my emotions. I think its main appeal to me since childhood has been the comfort it brings in knowing that at some point in time, another human felt the same thing as me and was able to survive and express it by making something beautiful. For my project, I recorded a 9 track album called Strange Machines while I was on leave of absence last year. This term, I created a 20 minute extended music video to accompany it. All of this lives on a page I coded on my personal website with some fun bonus content that I’ll scroll through at the end of this presentation. I’ll put the link in the comments so anyone who’s interested can check it out at their own pace. I have so much fun making music and feel proud when I have a cohesive finished product at the end. I’m not interested in becoming a virtuoso musician or a professional producer. A lot of trained musicians gatekeep, intimidate, and discourage amateurs. People mystify and mythologize the creative process as if it’s the product of some elusive, innate genius rather than practice, experimentation, and a simple love of music. As someone who’s work exists entirely as digital recordings, there’s no inherent reason for me to be an amazing guitar player who can play a song perfectly all the way through, as mistakes can be easily cut out and re-recorded. -

"Tin Soldiers and Nixon Coming": Musical Framing and Kent State Hayden Dingman Chapman University

Voces Novae Volume 4 Article 5 2018 "Tin Soldiers and Nixon Coming": Musical Framing and Kent State Hayden Dingman Chapman University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae Recommended Citation Dingman, Hayden (2018) ""Tin Soldiers and Nixon Coming": Musical Framing and Kent State," Voces Novae: Vol. 4 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae/vol4/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Voces Novae by an authorized editor of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dingman: "Tin Soldiers and Nixon Coming": Musical Framing and Kent State “Tin Soldiers and Nixon Coming” Voces Novae: Chapman University Historical Review, Vol 3, No 1 (2012) HOME ABOUT USER HOME SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES PHI ALPHA THETA Home > Vol 3, No 1 (2012) > Dingman "TIN SOLDIERS AND NIXON COMING": MUSICAL FRAMING AND KENT STATE Hayden Dingman On May 4, 1970, National Guardsmen in Kent, Ohio killed four students and wounded nine others at an anti-war rally in what was later termed the Kent State "massacre." Kent State University was a hotbed of activity in the week prior to the shootings, with students upset by President Richard Nixon's April 30 announcement of the Vietnam War's expansion into Cambodia. The May 4 protest was the culmination of four days and nights of events, including riots in downtown Kent on May 1 and the burning of the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) building on May 2. -

What Were the Forces That Led to the Rise of New Wave?

Are We Not New Wave? Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s Theo Cateforis http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=152565 The University of Michigan Press, 2011 Q&A with Theo Cateforis, author of Are We Not New Wave? Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s New wave emerged at the turn of the 1980s as a pop music movement cast in the image of punk rock's sneering demeanor, yet rendered more accessible and sophisticated. Artists such as the Cars, Devo, the Talking Heads, and the Human League leapt into the Top 40 with a novel sound that broke with the staid rock clichés of the 1970s and pointed the way to a more modern pop style. In Are We Not New Wave? Theo Cateforis provides the first musical and cultural history of the new wave movement, charting its rise out of mid- 1970s punk to its ubiquitous early 1980s MTV presence and downfall in the mid-1980s. The book also explores the meanings behind the music's distinctive traits—its characteristic whiteness and nervousness; its playful irony, electronic melodies, and crossover experimentations. Cateforis traces new wave's modern sensibilities back to the space-age consumer culture of the late 1950s/early 1960s. Theo Cateforis is Assistant Professor of Music History and Cultures in the Fine Arts Department at Syracuse University. His research is in the areas of American Music, Popular Music Studies, and Twentieth-Century Art Music. He was editor of the anthology The Rock History Reader. The University of Michigan Press: What were the forces that led to the rise of new wave? Theo Cateforis: New wave initially circulated as a synonym for the punk rock movement that emerged in the mid-1970s. -

Bloomsbury MUSIC Cat.Indd

MUSIC & SOUND STUDIES 2013-14 CELEBRATING 10 YEARS 33 1/3 is a series of short books about popular music, focusing on individual albums by a variety of artists. Launched in 2003, the series will publish its 100th book in 2014 and has been widely acclaimed and loved by fans, musicians and scholars alike. LAUNCHING SPRING 2014 new in 2013 new in 2013 new in 2014 9781623562878 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623569150 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623567149 $14.95 | £8.99 new in 2014 new in 2014 new in 2014 Bloomsbury Collections delivers instant access to quality research and provides libraries with a exible way to build ebook collections. 9781623568900 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623560652 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623562588 $14.95 | £8.99 Including ,+ titles in subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, the platform features content from Bloomsbury’s latest research publications as well as a + year legacy including Continuum, Berg, Bristol Classical Press, T&T Clark and The Arden Shakespeare. ■ Music & Sound Studies collection ■ Search full text of titles; browse available in , including ebooks by speci c subject new in 2014 new in 2014 new in 2014 from the Continuum archive ■ Download and print chapter PDFs ■ Instant access to s of key works, without DRM restriction easily navigable by research topic ■ Cite, share and personalize content RECOMMEND TO YOUR LIBRARY & SIGN UP FOR NEWS ▶ 9781623561222 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623561833 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623564230 $14.95 | £8.99 REGISTER FOR LIBRARY TRIALS AND QUOTES ▶ bloomsbury.com • 333sound.com • @333books [email protected] www.bloomsburycollections.com BC ad A5 (music).indd 1 08/10/2013 14:19 CONTENTS eBooks Contents eBook availability is indicated under each book entry: Individual eBook: available for your e-reader. -

![[ ALTERNATIVE by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 408 ] 28 DAYS >> SONG](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9812/alternative-by-artist-no-of-tunes-408-28-days-song-3289812.webp)

[ ALTERNATIVE by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 408 ] 28 DAYS >> SONG

[ ALTERNATIVE by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 408 ] 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO A >> STARBUCKS ALIEN ANT FARM >> GLOW ALIEN ANT FARM >> MOVIES ALIEN ANT FARM >> SMOOTH CRIMINAL {K} ALL AMERICAN REJECTS >> GIVES YOU HELL {K} ANDREW W K >> WE WANT FUN ANDROIDS >> DO IT WITH MADONNA {K} ARCTIC MONKEYS >> I BET YOU LOOK GOOD ON THE DANCE FLOOR AREA 7 >> START MAKING SENSE ASHLEE SIMPSON >> LA LA {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> GIRLFRIEND {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> HERE'S TO NEVER GROWING UP {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> MY HAPPY ENDING {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> SK8ER BOI {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> SMILE {K} BABY ANIMALS >> RUSH YOU BEASTIE BOYS >> BODY MOVIN BEASTIE BOYS >> INTERGALATIC BEN FOLDS FIVE >> ROCKIN' THE SUBURBS BIG AUDIO DYNAMITE >> RUSH BLACK KEYS >> LONELY BOY {K} BLIND MELON >> NO RAIN BLINK 182 >> ALL THE SMALL THINGS {K} BLINK 182 >> BORED TO DEATH BLINK 182 >> DAMMIT BLINK 182 >> I MISS YOU {K} BLINK 182 >> MAN OVERBOARD {K} BLINK 182 >> ROCK SHOW BLINK 182 >> WHAT'S MY AGE BLOODHOUND GANG >> FIRE WATER BURN BLUR >> CRAZY BEAT BLUR >> SONG 2 BODY ROCKERS >> I LIKE THE WAY {K} BODYJAR >> FALL TO THE GROUND {K} BODYJAR >> TOO DRUNK TO DRIVE BUSTED >> WHAT I GO TO SCHOOL FOR CAKE >> SHORT SKIRT - LONG JACKET CALLING >> OUR LIVES CARDIGANS >> MY FAVOURITE GAME CITIZEN KING >> BETTER DAYS COLDPLAY >> DON'T PANIC COLDPLAY >> EVERY TEARDROP IS A WATERFALL COLDPLAY >> PARADISE COLDPLAY >> SPEED OF SOUND {K} COLDPLAY >> TALK {K} CORNERSHOP