A Reading of Selected Poems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malayalam Syllabus 2020-21Onwards

ST.PHILOMENA’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), MYSURU (AFFILIATED TO UNIVERSITY OF MYSORE) REACCREDITED BY NAAC WITH B++ GRADE UNDER GRADUATE COURSE – SEMESTER SCHEME Academic year 2020-21 onwards DEPARTMENT OF MALAYALAM St. Philomena’s College (Autonomous), Mysore. Malayalam Syllabus under -2020-21 onwards Page 1 ST. PHILOMENA’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), MYSURU- 570015 Subject: Malayalam Syllabus for B.A/BBA/BCA/B.SC/BSW/B.COM Course under Semester Scheme. DURATION: TWO YEARS - FOUR SEMESTERS The Scheme of Teaching & Examination From the Academic Year – 2020-2021 Onwards Teaching & Examination Scheme Credit Scheme Title of the Paper TheorHours per Week Max. Marks Credits Duration in Semester y Hours Theory I A Total I Poetry, Prose and Precis writing 04 04 03 70 30 100 II Poetry, Drama and Translation 04 04 03 70 30 100 III Poetry ,Short stories and Letter 04 04 03 70 30 100 writing IV Poetry, Novel and General Essay 04 04 03 70 30 100 St. Philomena’s College (Autonomous), Mysore. Malayalam Syllabus under -2020-21 onwards Page 2 ST. PHILOMENA’S COLLEGE (Autonomous), MYSURU-570 015 Subject: Malayalam REVISED SYLLABUS FOR B.A, B.Sc, B S W, B.Com, B.B.M and BCA UNDER SEMESTER SCHEME From The Academic Year2020-21 Onwards Department of Malayalam Revised the syllabus for the Degree course in the academic year 2016- 17. This is the Second Language syllabus for B.A/B.Sc/B.Com/BBM/BCA & BSW Courses. This syllabus consists of Poetry, Prose and functional language. Poetry section includes poetry from different poets, representing old, medieval and modern age. -

English Books Details

1 Thumbnail Details A Brief History of Malayalam Language; Dr. E.V.N. Namboodiri The history of Malayalam Language in the background of pre- history and external history within the framework of modern linguistics. The author has made use of the descriptive analysis of old texts and modern dialects of Malayalam prepared by scholars from various Universities, which made this study an authoritative one. ISBN : 81-87590-06-08 Pages: 216 Price : 130.00 Availability: Available. A Brief Survey of the Art Scenario of Kerala; Vijayakumar Menon The book is a short history of the painting tradition and sculpture of Kerala from mural to modern period. The approach is interdisciplinary and tries to give a brief account of the change in the concept, expression and sensibility in the Art Scenario of Kerala. ISBN : 81-87590-09-2 Pages: 190 Price : 120.00 Availability: Available. An Artist in Life; Niharranjan Ray The book is a commentary on the life and works of Rabindranath Tagore. The evolution of Tagore’s personality – so vast and complex and many sided is revealed in this book through a comprehensive study of his life and works. ISBN : Pages: 482 Price : 30.00 Availability: Available. Canadian Literature; Ed: Jameela Begum The collection of fourteen essays on cotemporary Canadian Literature brings into focus the multicultural and multiracial base of Canadian Literature today. In keeping the varied background of the contributors, the essays reflect a wide range of critical approaches: feminist, postmodern, formalists, thematic and sociological. SBN : 033392 259 X Pages: 200 Price : 150.00 Availability: Available. 2 Carol Shields; Comp: Lekshmi Prasannan Ed: Jameela Begum A The monograph on Carol Shields, famous Canadian writer, is the first of a series of monographs that the centre for Canadian studies has designed. -

List of Books 2018 for the Publishers.Xlsx

LIST I LIST OF STATE BARE ACTS TOTAL STATE BARE ACTS 2018 PRICE (in EDITION SL.No. Rupees) COPIES AUTHOR/ REQUIRED PRICE FOR EDN / YEAR PUBLISHER EACH COPY APPROXIMATE K.G. 1 Abkari Laws in Kerala Rajamohan/Ar latest 898 5 4490 avind Menon Govt. 2 Account Code I Kerala latest 160 10 1600 Publication Govt. 3 Account Code II Kerala latest 160 10 1600 Publication Suvarna 4 Advocates Act latest 790 1 790 Publication Advocate's Welfare Fund Act George 5 & Rules a/w Advocate's Fees latest 120 3 360 Johnson Rules-Kerala Arbitration and Conciliation 6 Rules (if amendment of 2016 LBC latest 80 5 400 incorporated) Bhoo Niyamangal Adv. P. 7 latest 1500 1 1500 (malayalam)-Kerala Sanjayan 2nd 8 Biodiversity Laws & Practice LBC 795 1 795 2016 9 Chit Funds-Law relating to LBC 2017 295 3 885 Chitty/Kuri in Kerala-Laws 10 N Y Venkit 2012 160 1 160 on Christian laws in Kerala Santhosh 11 2007 520 1 520 Manual of Kumar S Civil & Criminal Laws in 12 LBC 2011 250 1 250 Practice-A Bunch of Civil Courts, Gram Swamy Law 13 Nyayalayas & Evening 2017 90 2 180 House Courts -Law relating to Civil Courts, Grama George 14 Nyayalaya & Evening latest 130 3 390 Johnson Courts-Law relating to 1 LIST I LIST OF STATE BARE ACTS TOTAL STATE BARE ACTS 2018 PRICE (in EDITION SL.No. Rupees) COPIES AUTHOR/ REQUIRED PRICE FOR EDN / YEAR PUBLISHER EACH COPY APPROXIMATE Civil Drafting and Pleadings 15 With Model / Sample Forms LBC 2016 660 1 660 (6th Edn. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Indian Scholar

ISSN 2350-109X Indian Scholar www.indianscholar.co.in An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal THE RISE AND GROWTH OF CHILDREN’S POETRY IN MALAYALAM LITERATURE Kavya. T Guest Lecturer in English MPMMSN Trusts College, Shoranur It is a quintessential human nature to compare, contrast and weigh the value of anything in the world. Perhaps it is our need to put order into an otherwise chaotic life that drives us to categorize everything. Our culture, tradition, art and literature are not exempted from this grading process. Thus it is quite natural that children’s literature got relegated to the peripheries of mainstream literature. This marginalization is universal and Malayalam literature too avoided it as trivial and childish. But now a days Children’s literature is gaining popularity in academic circles with many a scholars opening up new areas of researches in the field. Thus it would be meaningful to trace the trajectory of poems for children in Malayalam literature. A child’s acquaintance with poetry starts from the womb itself. This grows into much stronger relation as he/she is tucked into sleep with sweet lullabies by mother. Thus poetry is the first literature presented to a child.Offering comfort and happiness in rhythm and sounds these verses prepare the developing minds to receive longer forms of literature. But still there are debates regarding the characteristics of verses that can be categorized as children’s poems. Sheila aEgoff in Thursday’s Child questions “Is poetry for children a separate territory, or is -

K. Satchidanandan

1 K. SATCHIDANANDAN Bio-data: Highlights Date of Birth : 28 May 1946 Place of birth : Pulloot, Trichur Dt., Kerala Academic Qualifications M.A. (English) Maharajas College, Ernakulam, Kerala Ph.D. (English) on Post-Structuralist Literary Theory, University of Calic Posts held Consultant, Ministry of Human Resource, Govt. of India( 2006-2007) Secretary, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi (1996-2006) Editor (English), Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi (1992-96) Professor, Christ College, Irinjalakuda, Kerala (1979-92) Lecturer, Christ College, Irinjalakuda, Kerala (1970-79) Lecturer, K.K.T.M. College, Pullut, Trichur (Dt.), Kerala (1967-70) Present Address 7-C, Neethi Apartments, Plot No.84, I.P. Extension, Delhi 110 092 Phone :011- 22246240 (Res.), 09868232794 (M) E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Other important positions held 1. Member, Faculty of Languages, Calicut University (1987-1993) 2. Member, Post-Graduate Board of Studies, University of Kerala (1987-1990) 3. Resource Person, Faculty Improvement Programme, University of Calicut, M.G. University, Kottayam, Ambedkar University, Aurangabad, Kerala University, Trivandrum, Lucknow University and Delhi University (1990-2004) 4. Jury Member, Kerala Govt. Film Award, 1990. 5. Member, Language Advisory Board (Malayalam), Sahitya Akademi (1988-92) 6. Member, Malayalam Advisory Board, National Book Trust (1996- ) 7. Jury Member, Kabir Samman, M.P. Govt. (1990, 1994, 1996) 8. Executive Member, Progressive Writers’ & Artists Association, Kerala (1990-92) 9. Founder Member, Forum for Secular Culture, Kerala 10. Co-ordinator, Indian Writers’ Delegation to the Festival of India in China, 1994. 11. Co-ordinator, Kavita-93, All India Poets’ Meet, New Delhi. 12. Adviser, ‘Vagarth’ Poetry Centre, Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal. -

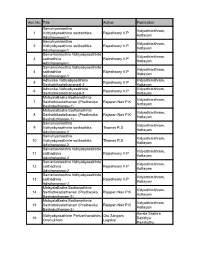

Library Stock.Pdf

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

English Literature STANDARD XII

Higher Secondary Course Part III English Literature STANDARD XII GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION 2015 PLEDGE THE NATIONAL ANTHEM India is my country. All Indians Jana-gana-mana-adhinayaka, jaya he are my brothers and sisters. I love Bharata-bhagya-vidhata. my country, and I am proud of Punjab-Sindh-Gujarat-Maratha its rich and varied heritage. I shall Dravida-Utkala-Banga always strive to be worthy of it. Vindhya-Himachala-Yamuna-Ganga I shall give my parents, teachers Uchchala-Jaladhi-taranga. and all elders respect, and treat Tava shubha name jage, everyone with courtesy. Tava shubha asisa mage, To my country and my people, I Gahe tava jaya gatha, pledge my devotion. In their Jana-gana-mangala-dayaka jaya he well-being and prosperity alone Bharata-bhagya-vidhata. lies my happiness. Jaya he, jaya he, jaya he, Jaya jaya jaya, jaya he! Higher Secondary Course - English Literature Optional - Part III Standard XII Prepared by: State Council of Educational Research & Training (SCERT) Poojappura, Thiruvananthapuram -12, Kerala. E-mail: [email protected] Typesetting by: SCERT Computer Lab Printed at: Kerala State C-apt, Thiruvananthapuram, Ph: 0471-2365415 © Government of Kerala Department of Education 2015 Dear learners The English Literature Coursebook for Standard XII has been designed with a view to developing literary taste, critical reading skills, skills in expressing your ideas both in the spoken and written forms and reference skills. The learning of any language inevitably involves the learning of its rich and varied literature. The selections in this book represent authors from different cultures ranging from W B Yeats to Sugathakumari and Salwa Bakr to Leopoldo Lugones. -

MA Syllbus 2014 Revised 17 8 14

SYLLABUS FOR M.A. PROGRAMME IN SANSKRIT SAHITYA (2014 June onwards) The syllabus of M.A. programme in Sanskrit Sahitya (Course Credit and Semester System) is being restructured in order to satisfy the contemporary requirements on the basis of the recent developments in the academic field. To provide an interdisciplinary nature to the courses, some areas of studies are developed, changed and/or redefined. M.A. programme is consisted of four semesters. Total number of courses is 20. Each course is having 4 credits. Thus the student has to acquire a minimum total of 80 credits for completing the programme. Among the 20 courses of the PG programme, 7 are electives/optionals out of which 5 should be from the parent department(Internal Electives) and the remaining two must be, from any other departments(multidisciplinary electives). There will be five courses in each semester and five hours are distributred for each course. There will be 3 core courses and two elective/optional course in each semester. In the first and fourth semesters, elective/optional courses are to be taken from within the parent department from the internal electives given in the list and in the second and third, it has to be from other departments. Students of other departments can opt the multidisciplinary elective courses offerd by the Department of Sanskrit Sahitya in the second and third semesters and the students may write answers either in Sanskrit, or in English or in Malayalam The Course 20, ie, ProjectCourse No:1 (Dissertation) will be in the form of the presentation of seminar and a project work done by each and every student. -

The Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and Fiction: Translations from European Languages Into Malayalam in the First Half of the Twentieth Century

The Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and Fiction: Translations from European Languages into Malayalam in the First Half of the Twentieth Century K.M. Sherrif Abstract Translations from European languages have played a crucial role in the evolution of Malayalam prose and fiction in the first half of the Twentieth Century. Many of them are directly linked to the socio- political movements in Kerala which have been collectively designated ‘Kerala’s Renaissance.’ The nature of the translated texts reveal the operation of ideological and aesthetic filters in the interface between literatures, while the overwhelming presence of secondary translations indicate the hegemonic status of English as a receptor language. The translations never occupied a central position in the Malayalam literature and served mostly as mere literary and political stimulants. Keywords: Translation - evolution of genres, canon - political intervention The role of translation in the development of languages and literatures has been extensively discussed by translation scholars in the West during the last quarter of a century. The proliferation of diachronic translation studies that accompanied the revolutionary breakthroughs in translation theory in the mid-Eighties of the Twentieth Century resulted in the extensive mapping of the intervention of translation in the development of discourses and shifts of ideological paradigms in cultures, in the development of genres and the construction and disruption of the canon in literatures and in altering the idiomatic and structural paradigms of languages. One of the most detailed studies in the area was made by Andre Lefevere (1988, pp 75-114) Lefevere showed with convincing 118 Translation Today K.M. -

Tamil New Poetry: Twentieth Century Tamil Poets #9788189020460 #2005 #Katha, 2005

Tamil New Poetry: Twentieth Century Tamil Poets #9788189020460 #2005 #Katha, 2005 Tamil New Poetry: Twentieth Century Tamil Poets Most of Jeffersâ™ poetry was written in classic narrative and epic form, but today he is also known for his short verse, and considered an icon of the environmental movement. He is generally considered to be among the greatest American poets of the twentieth century. The old South Boston Aquarium stands in a Sahara of snow now. Its broken windows are boarded. So modern poetry is essentially a private art form and it contains very much a story of individual poets. The most striking thing in twentieth-century English literature is the revolution in poetic taste and practice. Various movements and changes had a greater influence upon modern poetry. Though poets are often influenced by each other and sometimes, share a common outlook, their style and the ways of writing differ from each other. So modern poetry is essentially a private art form and it contains very much a story of individual poets. T. S. Eliot. He is one of the most remarkable of English poets. He had great influence on poetry for more than forty years. He has used a new form of poetry to describe his new experience. His language has great life and energy. Conclusion. This list of Indian poets consists of poets of Indian ethnic, cultural or religious ancestry either born in India or emigrated to India from other regions of the world. Amulya Barua (1922â“1946), first published posthumously in 1964. Atul Chandra Hazarika (1903â“1986), poet, dramatist, children's story writer and translator. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions