Modern Asian Studies Secularizing the Sacred, Imagining the Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscaping India: from Colony to Postcolony

Syracuse University SURFACE English - Dissertations College of Arts and Sciences 8-2013 Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony Sandeep Banerjee Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Geography Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sandeep, "Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony" (2013). English - Dissertations. 65. https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd/65 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in English - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT Landscaping India investigates the use of landscapes in colonial and anti-colonial representations of India from the mid-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries. It examines literary and cultural texts in addition to, and along with, “non-literary” documents such as departmental and census reports published by the British Indian government, popular geography texts and text-books, travel guides, private journals, and newspaper reportage to develop a wider interpretative context for literary and cultural analysis of colonialism in South Asia. Drawing of materialist theorizations of “landscape” developed in the disciplines of geography, literary and cultural studies, and art history, Landscaping India examines the colonial landscape as a product of colonial hegemony, as well as a process of constructing, maintaining and challenging it. In so doing, it illuminates the conditions of possibility for, and the historico-geographical processes that structure, the production of the Indian nation. -

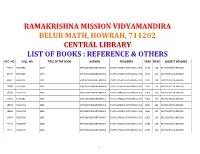

Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira Belur Math, Howrah, 711202 Central Library List of Books : Reference & Others Acc

RAMAKRISHNA MISSION VIDYAMANDIRA BELUR MATH, HOWRAH, 711202 CENTRAL LIBRARY LIST OF BOOKS : REFERENCE & OTHERS ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 44638 R032/ENC 1978 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1978 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44639 R032/ENC 1979 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1979 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44641 R-032/BRI 1981 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1981 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15648 R-032/BRI 1982 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1982 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15649 R-032/ENC 1983 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1983 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 17913 R032/ENC 1984 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1984 350 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18648 R-032/ENC 1985 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1985 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18786 R-032/ENC 1986 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1986 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 19693 R-032/ENC 1987 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1987 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21140 R-032/ENC 1988 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1988 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21141 R-032/ENC 1989 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1989 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 1 ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 21426 R-032/ENC 1990 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1990 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21797 R-032/ENC 1991 ENYCOLPAEDIA -

Bengali Perceptions of the Sikhs: the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

,XT O ftY£~, ~J'rcLtb- \Lc~rJA - &y j4--£h*£as'' ! e% $ j Bengali Perceptions of the Sikhs: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries *> ■ Himadri Banerjee I L Nowadays the “study of history from below” is receiving serious attention Oi ‘ cholars in the subcontinent. Against this background, this chapter may not evoke much enthusiasm, for it is apparently based on a “horizontal approach” to • history. To a casual observer it may also convey an impression of an exclusive middle-class literary endeavour, catering merely to its middle-class needs. But. beyond this narrow limit, the chapter tries lo trace the efforts of a community to r> * *. understand one of its distant neighbours over the years.1 Of these efforts, nineteenth- and twentieth-century Bengali writing dealing with Sikhs has been a V meaningful index. Bengali interest in understanding the Sikhs is reflected in a number of nineteenth-century works, and it continues to the present. A good number of Bengali writers were associated with this endeavour, and different factors brought them together on a common platform. They came from different walks '.if of life: they were poets, historians, essayists, journalists, religious reformers, political leaders and dramatists. A few of them spent long years in the Punjab, where they had gone following the British annexation (1849) in response to the growing administrative needs of the colonial government. They often tried to communicate their local experience and knowledge of the Sikhs to their own v people at home. The majority of these writers were, however, of the city of Calcutta, then f \ tnessing a growing upsurge of militant nationalist opposition to British rule. -

Chapter 2 DEVELOPMENT of PUBLIC LIBRARIES in COLONIAL

Chapter 2 DEVELOPMENT OF PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN COLONIAL BENGAL There is no evidence of East India Company’s interest in the education of Bengal till the end of the eighteenth century. We have not found any distinct picture of mass education in England prior to 1780, and the question to show interest to spread mass education in Bengal was beyond the thought of company till end of eighteenth century as it was general perception that it could be spread without state intervention. The Directors of the East India Company were interested mainly in the expansion of trade, commerce and political influence in India. They did not bother about the intellectual and moral upliftment of the general people of the country. So, the question of mass education in Bengal did not receive any serious consideration from the East India Company in its early years. The expansion of primary education ought to have been the primary responsibility of the government of the country. But unfortunately, the government policy in this regard was not bold and adequate up to late 19th and early 20th centuries which was precondition to set up public libraries. The rate of growth of literacy in Bengal during the period in table below show the progress was too slow and halting. 1 LITERACY IN BENGAL The rate of growth of literacy in Bengal during 1881 to 1911 in table below shows the progress was too slow and halting. Table 2.1: Growth of literacy in districts of Bengal1 Name of the District Percentage of literates 1881 1891 1901 1911 Bankura 5.23 6.45 9.28 9.43 Birbhum 4.44 6.28 -

The Transformation of Domesticity As an Ideology: Calcutta, 1880-1947

The Transformation of Domesticity as an Ideology: Calcutta, 1880-1947. by Sudeshna Baneijee Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts of the University of London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies, London Department of History 1997 /BIBL \ {uDNm) \tmiV ProQuest Number: 10672991 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672991 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This study of the ideology of domesticity among the Bengali Hindu middle-class of Calcutta between 1880 and 1947 problematises the relation between anti-colonial nationalism and domesticity by contextualising it in a social history perspective. The thesis argues that the nationalist domestic ideology of the class was not a mere counter-discursive derivative of colonial power/knowledge. Its development was a dialectical process; in it the agency of the lived experience of domesticity, as the primary level of this group’s reproduction of its class identity, material anxieties, status, and gender ideology, interacted with nationalist counter- discursive abstractions. This dialectic, the thesis argues, made the domestic ideology of the colonial middle class a transforming entity. -

TOURISM 2007 01E A

Dipankar Chatterjee, Arnab Das, Fulguni Ganguli and Liton Dey Domestic tourism of the urban Bengalis: A shared observation of the culture Abstract The research reported in this paper attempts to give an overview of the culture concerning domestic tourism of the urban Bengalis, the linguistically distinct people of India. The urban Bengalis, especially the people of Kolkata metropolis are, since colonial period, one of the largest sections of the tourists in India. This paper is an exploration of relationship between the signifi- cant Bengali representations of travel and the contemporary preferences of urban Bengali domestic tourists. With that objective, the authors, being Bengali themselves, tried to encompass and analyse all the significantly popular Bengali representation in literature, films and other agencies centred on tourism and also the real experience of the purposively selected one hundred contempo- rary tourists from Bengali families living in Kolkata metropolis. The former is seen to prevail as the backdrop of the later, though the later is undergoing some shifts from the former vision. The observation shows that the decision-making for the domestic tours of the Bengalis depends on the locally understood criteria of preferences and the specific operation of the criteria as actively selected by the tourists. A current account of preferences of the informants is given in order to focus on the present trends of preferred domestic tours. The approach of the work ultimately explores the repertoire of the varied, but changing cultural motivation and representation of the tourists, the continuity and change in the trends of domestic tours of the Bengalis, and other relevant issues of the local internal tourism. -

January 2005

MOTHER INDIA MONTHLY REVIEW OF CULTURE Vol. LVIII No. 1 “Great is Truth and it shall prevail” CONTENTS Sri Aurobindo THE INFINITE ADVENTURE (Poem) ... 1 The Mother ‘THE REDEMPTION AND PURIFICATION OF MATTER’ ... 2 ‘GRANT, O LORD, THAT I MAY BE...’ ... 3 Sri Aurobindo ‘KATOSHATO CHANDOBANDHE...’ (Poem in Bengali) ... 4 NATARAJA (English Translation by Richard Hartz) ... 4 ON IDEALS ... 5 Nolini Kanta Gupta SELECTIONS FROM NOLINI KANTA GUPTA’S WRITINGS ... 10 A LETTER ... 10 TO READ SRI AUROBINDO ... 12 MEAT-EATING ... 16 A YOGA OF THE ART OF LIFE ... 18 THE SOUL’S ODYSSEY ... 21 YOGA AS PRAGMATIC POWER ... 23 HYMN TO SURYA (A Translation) ... 25 Amal Kiran (K. D. Sethna) QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ON SAVITRI ... 26 Priti Das Gupta MOMENTS, ETERNAL ... 33 Debashish Banerji NIRODBARAN’S SURREALIST POEMS ... 44 Mangesh Nadkarni RAMANA MAHARSHI AND SRI AUROBINDO: THE RECONCILIATION OF KAPALI SASTRY ... 45 Nolinikanto Sarkar BETWEEN THE ARRIVAL AND THE DEPARTURE ... 52 Aniruddha Sircar FIRE (Poem) ... 59 Pravir Malik INDIA AT THE CROSSROADS ... 60 Mary “Angel” Finn SHAKTI OF THE SUN (Poem) ... 69 Prema Nandakumar THE PURANAS AND OUR CENTURY ... 70 Snehajeet Chatterjee O, THE LIGHT! (Poem) ... 79 R. Prabhakar (Batti) TIPS FROM THE TOP ... 80 Pradip Bhattacharya A CLEAR RAY AND A LAMP—AN EXCHANGE OF LIGHT ... 82 Sarani Ghosal Mondal MANMOHAN GHOSE: A RE-VALUATION ... 89 Hemant Kapoor ONENESS (Poem) ... 99 Amita Sen MONSIEUR AND MADAME FRANÇOIS MARTIN IN PONDICHERRY ... 100 Pujalal NAVANIT: STORIES RETOLD ... 106 1 THE INFINITE ADVENTURE On the waters of a nameless Infinite My skiff is launched; I have left the human shore. All fades behind me and I see before The unknown abyss and one pale pointing light. -

Gauri Ma – a Monastic Disciple of Sri Ramakrishna

Gauri Ma – A Monastic Disciple of Sri Ramakrishna By Swami Shivatatvananda Published by Mothers Trust/Mothers Place Translator's Note Foreword Unless He Drags Me Meeting at Dakshineswar First Encounter and Initiation Childhood Tendencies Captive Bird Austerity in the Himalayas On Pilgrimage in Search of Krishna Master and Disciple Part II: Flowers of Service to the Living Mother Sri Ramakrishna's Behest The Mahasamadhi of Sri Ramakrishna Pilgrimage and Solace How to Ease the Suffering of Women? Sri Saradeshwari Ashram Early Days in Calcutta Establishing a Permanent Foundation Performing the Work of the Lord Selflessness and Compassion The Spiritual Education of Women Master and Disciple Meet Again Glossary It was at the Vivekananda Vedanta Society of Chicago that we first heard about Sannyasini Mataji Gauri Ma. Swami Bhashyananda, a monk of the Ramakrishna Order and head of the Vivekananda Vedanta Society in Chicago and the Vivekananda Monastery and Retreat in Ganges, Michigan, would read and translate the story of her life to us from the original Marathi. It was a tale that captivated our hearts and minds. Years later, as our memories dimmed, we longed to hear the story of her life once again – and share it with others. That was the motivation that began this book. Swami Bhashyananda gave us all the encouragement we needed. The task was formidable and many long hours were spent on the project, but it was a source of great joy to us. This short biography by Swami Shivatatvananda, a monk of the Ramakrishna Order, was first published in three parts in the magazine Jivan Vikas (vol. -

To Get the File

THE POWER 4 OF THE PRINTED IMAGE In principle a work of art has always been reproducible . Mechanical reproduction of a work of art, however, represents something new. Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, 1955 THE RISE OF PICTORIAL JOURNALISM Art schools and art societies, the new institutions that helped to establish the supremacy of academic art in Bombay and Calcutta, enjoyed Raj patronage. But there were modern innovations, namely printing technol- ogy and the processes of mechanical reproduction, that flourished independently of the government. These means of mass communication made further assaults on Indian sensibility, turning urban India into a 'visual society', dominated by the printed image. They affected equally the elite and the ordinary people: lithographic prints served a mass market that cut across class barriers, while pictorial journalism became an indispensable part of literate culture. The educated enjoyed a rich harvest, of illustrated magazines, picture books for children and cartoons. The . appearance of high-quality plates lent greater credibility to writings on \ art. As printing presses mushroomed, these publications reinforced public taste for academic art. The mechanical production of images opened up endless possibilities for the enterprising journalist. Graphic artists, for instance, served their apprenticeship as illustrators and cartoonists on magazines. For a remark- able flair in blending literary and illustrative journalism we must turn to the brilliant early practitioner, Ramananda Chatterjee. His career co- incided with the Bengal Renaissance and the founding of the Indian National Congress in 1885. In 1909, the influential editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, W. T. Stead, paid a tribute to this pioneer: the sanest Indians are for a 'nationhood of India', undivided by caste, religion or racial differences. -

E-Tender P a G E ||| 111

Notice Inviting e-Tender P a g e ||| 111 NIT [ NOTICE INVITING e-TENDER ] No. : WBKP/CP/NIT - 175 / BENGALI BOOKS FOR LIBRARY /TEN Dated : 24 / 09 /201 8 e-Tender FOR PROCUREMENT OF BENGALI BOOKS FOR KOLKATA POLICE LIMELIGHT LIBRARY KOLKATA POLICE DIRECTORATE Tender Section, 18, Lalbazar Street, Kolkata – 700 001. Ph. : (033) 2250 5275 / (033) 2250-5048 e-Mail : [email protected] 222 ||| P a g e Notice Inviting e-Tender TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTICE INVITING e-TENDER .................................................................................................................................. 3 I. PRE-BID QUALIFICATIONS ............................................................................................ 4 1. Company Registration : ...................................................................................................................... 4 2. Undertaking Regarding Blacklisting : ................................................................................................. 4 3. Partnership Firm (if applicable) :........................................................................................................ 4 4. Annual Turnover : ............................................................................................................................... 4 5. Work Experience : ............................................................................................................................... 4 6. PAN No. : ............................................................................................................................................. -

EVOLUTION of BENGALI LITERATURE: an OVERVIEW Dr

Int.J.Eng.Lang.Lit&Trans.StudiesINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE, Vol. LITERATURE3.Issue. 1.2016 (Jan-Mar) AND TRANSLATION STUDIES (IJELR) A QUARTERLY, INDEXED, REFEREED AND PEER REVIEWED OPEN ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL http://www.ijelr.in KY PUBLICATIONS REVIEW ARTICLE Vol. 3. Issue 1.,2016 (Jan-Mar. ) EVOLUTION OF BENGALI LITERATURE: AN OVERVIEW Dr. PURNIMA BALI Assistant Professor (English), Department of Applied Sciences, A P Goyal Shimla University, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India ABSTRACT Indian literature is full of various genres of literature in different languages. Bengali is one of the prominent languages in which literature enriched itself the most. Bengali literature refers to the body of writings in the Bengali language which has developed from a form of Prakrit or Indo-Aryan language. The Bengali literature has been divided into three main periods - ancient, medieval and modern. These different periods may be dated as: ancient period from 950 AD to 1350 AD, medieval from 1350 AD to 1800 AD and the modern one from 1800 AD to the present. Many literary scholars and intellectual minds belong to the Bengali literature. The present paper dwells upon the historical background of West Bengal along with the evolution of Bengali literature from the ancient period till date. The paper will focus primarily on the detailed study of eminent writers of Bengali literature whose works are being translated into various other languages so that their thoughts can be spread over the masses. Key Words: Literature, Bengali language, West Bengal, Writers, Literary writings ©KY PUBLICATIONS Historical Background of West Bengal West Bengal is one of the major states of India situated in the Eastern part of the country. -

Hitesranjan Sanyal Memorial Collection

A guide to the Hitesranjan Sanyal Memorial Collection an archival collection of old Bangla periodicals; documents relating to the social history of Bengal and the Communist Parties of India and Great Britain in microfilm rolls; colour transparencies of 19th and early 20th century paintings, lithographs and photographs; reports of the Indian Census, 1872-1951, and Occasional Papers of the CSSSC on microfiche cards at Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta 10, Lake Terrace Calcutta 700 029 Abhijit Bhattacharya Published by : Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, 10 Lake Terrace, Calcutta 700 029.April, 1998. Copyright: Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, 1998 The CSSSC is grateful to the ENRECA programme of DANIDA and the India Foundation for the Arts for their financial assistance towards the setting up of this archive. Printed by : ALLIES, 26, Vivekananda Sarani, Calcutta - 700 078. About this guide : All documents available in microfilm rolls are arranged alphabetically. The ‘index of Bangla periodicals’ and the ‘subject index’ located at the end of the guide refer to entry numbers; the ‘index of names’ refer to page numbers. Microfiches of Occasional Papers of the CSSSC and transparencies of visual materials are listed at the end of the guide; there is no corresponding ‘subject index’ to these items. For Government Reports and Proceedings, the name of the department to which the document is related is mentioned first. In case of Reports of Commissions appointed by the government or any of its agencies, the title is shown as it appears on the title page of the manuscript or printed report.