The Transformation of Domesticity As an Ideology: Calcutta, 1880-1947

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES and the LANGUAGE of POLITICS in LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(L921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT and REACTION

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(l921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL BY KOUSHIKIDASGUPTA ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF GOUR BANGA MALDA UPERVISOR PROFESSOR I. SARKAR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL RAJA RAMMOHANPUR, DARJEELING WEST BENGAL 2011 IK 35 229^ I ^ pro 'J"^') 2?557i UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL Raja Rammohunpur P.O. North Bengal University Dist. Darjeeling - 734013 West Bengal (India) • Phone : 0353 - 2776351 Ref. No Date y.hU. CERTIFICATE OF GUIDE AND SUPERVISOR Certified that the Ph.D. thesis prepared by Koushiki Dasgupta on Minor Political Parties and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial Bengal ^921-194'^ J Attitude, Adjustment and Reaction embodies the result of her original study and investigation under my supervision. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this study is the first of its kind and is in no way a reproduction of any other research work. Dr.LSarkar ^''^ Professor of History Department of History University of North Bengal Darje^ingy^A^iCst^^a^r Department of History University nfVi,rth Bengal Darjeeliny l\V Bj DECLARATION I do hereby declare that the thesis entitled MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL (l921- 1947); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION being submitted to the University of North Bengal in partial fulfillment for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in History is an original piece of research work done by me and has not been published or submitted elsewhere for any other degree in full or part of it. -

Freedom in West Bengal Revised

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Freedom and its Enemies: Politics of Transition in West Bengal, 1947-1949 * Sekhar Bandyopadhyay Victoria University of Wellington I The fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence became an occasion for the publication of a huge body of literature on post-colonial India. Understandably, the discussion of 1947 in this literature is largely focussed on Partition—its memories and its long-term effects on the nation. 1 Earlier studies on Partition looked at the ‘event’ as a part of the grand narrative of the formation of two nation-states in the subcontinent; but in recent times the historians’ gaze has shifted to what Gyanendra Pandey has described as ‘a history of the lives and experiences of the people who lived through that time’. 2 So far as Bengal is concerned, such experiences have been analysed in two subsets, i.e., the experience of the borderland, and the experience of the refugees. As the surgical knife of Sir Cyril Ratcliffe was hastily and erratically drawn across Bengal, it created an international boundary that was seriously flawed and which brutally disrupted the life and livelihood of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, many of whom suddenly found themselves living in what they conceived of as ‘enemy’ territory. Even those who ended up on the ‘right’ side of the border, like the Hindus in Murshidabad and Nadia, were apprehensive that they might be sacrificed and exchanged for the Hindus in Khulna who were caught up on the wrong side and vehemently demanded to cross over. -

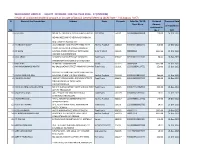

(INTERIM) Details of Unclaimed Dividend Amount As On

WOCKHARDT LIMITED - EQUITY DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2016 - 17 (INTERIM) Details of unclaimed dividend amount as on date of Annual General Meeting (AGM Date - 2nd August, 2017) SI Name of the Shareholder Address State Pin code Folio No / DP ID Dividend Proposed Date Client ID no. Amount of Transfer to unclaimed in No. (Rs.) IEPF 1 A G SUJAY NO 49 1ST MAIN 4TH CROSS HEALTH LAYOUT Karnataka 560091 1203600000360918 120.00 16-Dec-2023 VISHWANEEDAM PO NEAR NAGARABHAVI BDA COMPLEX BANGALORE 2 A HANUMA REDDY 302 HARBOUR HEIGHTS OPP PANCHAYAT Andhra Pradesh 524344 IN30048418660271 510.00 16-Dec-2023 OFFICE MUTHUKUR ANDHRA PRADESH 3 A K GARG C/O M/S ANAND SWAROOP FATEHGANJ Uttar Pradesh 203001 W0000966 3000.00 16-Dec-2023 [MANDI] BULUNDSHAHAR 4 A KALARANI 37 A(NEW NO 50) EZHAVAR SANNATHI Tamil Nadu 629002 IN30108022510940 50.00 16-Dec-2023 STREET KOTTAR NAGERCOIL,TAMILNADU 5 A M LAZAR ALAMIPALLY KANHANGAD Kerala 671315 W0029284 6000.00 16-Dec-2023 6 A M NARASIMMABHARATHI NO 140/3 BAZAAR STREET AMMIYARKUPPAM Tamil Nadu 631301 1203320004114751 250.00 16-Dec-2023 PALLIPET-TK THIRUVALLUR DT THIRUVALLUR 7 A MALLIKARJUNA RAO DOOR NO 1/1814 Y M PALLI KADAPA Andhra Pradesh 516004 IN30232410966260 500.00 16-Dec-2023 8 A NABESA MUNAF 46B/10 THIRUMANJANA GOPURAM STREET Tamil Nadu 606601 IN30108022007302 600.00 16-Dec-2023 TIRUVANNAMALAI TAMILNADU TIRUVANNAMALAI 9 A RAJA SHANMUGASUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST Tamil Nadu 614625 IN30177414782892 250.00 16-Dec-2023 AND TK THANJAVUR 10 A RAJESH KUMAR 445-2 PHASE 3 NETHAJI BOSE ROAD Tamil Nadu 632009 -

Premendra Mitra - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Premendra Mitra - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Premendra Mitra(1904 - 3 May 1988) Premendra Mitra was a renowned Bengali poet, novelist, short story writer and film director. He was also an author of Bangla science fiction and thrillers. <b>Life</b> He was born in Varanasi, India, though his ancestors lived at Rajpur, South 24 Parganas, West Bengal. His father was an employee of the Indian Railways and because of that; he had the opportunity of travelling to many places in India. He spent his childhood in Uttar Pradesh and his later life in Kolkata & Dhaka. He was a student of South Suburban School (Main) and later at the Scottish Church College in Kolkata. During his initial years, he (unsuccessfully) aspired to be a physician and studied the natural sciences. Later he started out as a school teacher. He even tried to make a career for himself as a businessman, but he was unsuccessful in that venture as well. At a time, he was working in the marketing division of a medicine producing company. After trying out the other occupations, in which he met marginal or moderate success, he rediscovered his talents for creativity in writing and eventually became a Bengali author and poet. Married to Beena Mitra, he was, by profession, a Bengali professor at City College in north Kolkata. He spent almost his entire life in a house at Kalighat, Kolkata. <b>As an Author & Editor</b> In November 1923, Mitra came from Dhaka, Bangladesh and stayed in a mess at Gobinda Ghoshal Lane, Kolkata. -

Balika Badhu: a Selected Anthology of Bengali Short Stories' Monish Ranjan Chatterjee University of Dayton, [email protected]

University of Dayton eCommons Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Department of Electrical and Computer Publications Engineering 2002 Translation of 'Balika Badhu: A Selected Anthology of Bengali Short Stories' Monish Ranjan Chatterjee University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ece_fac_pub Part of the Computer Engineering Commons, Electrical and Electronics Commons, Electromagnetics and Photonics Commons, Optics Commons, Other Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons, and the Systems and Communications Commons eCommons Citation Chatterjee, Monish Ranjan, "Translation of 'Balika Badhu: A Selected Anthology of Bengali Short Stories'" (2002). Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Publications. Paper 362. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ece_fac_pub/362 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Translator'sl?rcfacc This project, which began with the desire to render into English a rather long tale by Bimal Kar about five years ago, eventually grew into a considerably more extended compilation of Bengali short stories by ten of the most well known practitioners of that art since the heyday of Rabindranath Tagore. The collection is limited in many ways, not the least of which being that no woman writer has been included, and that it contains only a baker's dozen stories (if we count Bonophool's micro-stories collectively as one )-a number pitifully small considering the vast and prolific field of authors and stories a translator has at his or her disposal. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

The Hooghly River a Sacred and Secular Waterway

Water and Asia The Hooghly River A Sacred and Secular Waterway By Robert Ivermee (Above) Dakshineswar Kali Temple near Kolkata, on the (Left) Detail from The Descent of the Ganga, life-size carved eastern bank of the Hooghly River. Source: Wikimedia Commons, rock relief at Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu, India. Source: by Asis K. Chatt, at https://tinyurl.com/y9e87l6u. Wikimedia Commons, by Ssriram mt, at https://tinyurl.com/y8jspxmp. he Hooghly weaves through the Indi- Hooghly was venerated as the Ganges’s original an state of West Bengal from the Gan- and most sacred route. Its alternative name— ges, its parent river, to the sea. At just the Bhagirathi—evokes its divine origin and the T460 kilometers (approximately 286 miles), its earthly ruler responsible for its descent. Hindus length is modest in comparison with great from across India established temples on the Asian rivers like the Yangtze in China or the river’s banks, often at its confluence with oth- Ganges itself. Nevertheless, through history, er waterways, and used the river water in their the Hooghly has been a waterway of tremen- ceremonies. Many of the temples became fa- dous sacred and secular significance. mous pilgrimage sites. Until the seventeenth century, when the From prehistoric times, the Hooghly at- main course of the Ganges shifted decisively tracted people for secular as well as sacred eastward, the Hooghly was the major channel reasons. The lands on both sides of the river through which the Ganges entered the Bay of were extremely fertile. Archaeological evi- Bengal. From its source in the high Himalayas, dence confirms that rice farming communi- the Ganges flowed in a broadly southeasterly ties, probably from the Himalayas and Indian direction across the Indian plains before de- The Hooghly was venerated plains, first settled there some 3,000 years ago. -

Urban Ethnic Space: a Discourse on Chinese Community in Kolkata, West Bengal

Indian Journal of Spatial Science Spring Issue, 10 (1) 2019 pp. 25 - 31 Indian Journal of Spatial Science Peer Reviewed and UGC Approved (Sl No. 7617) EISSN: 2249 - 4316 homepage: www.indiansss.org ISSN: 2249 - 3921 Urban Ethnic Space: A Discourse on Chinese Community in Kolkata, West Bengal Sudipto Kumar Goswami Research Scholar, Department of Geography, Visva-Bharati, India Dr.Uma Sankar Malik Professor of Geography, Department of Geography, Visva-Bharati, India Article Info Abstract _____________ ___________________________________________________________ Article History The modern urban societies are pluralistic in nature, as cities are the destination of immigration of the ethnic diaspora from national and international sources. All ethnic groups set a cultural distinction Received on: from another group which can make them unlike from the other groups. Every culture is filled with 20 August 2018 traditions, values, and norms that can be traced back over generations. The main focus of this study is to Accepted inRevised Form on : identify the Chinese community with their history, social status factor, changing pattern of Social group 31 December, 2018 interaction, value orientation, language and communications, family life process, beliefs and practices, AvailableOnline on and from : religion, art and expressive forms, diet or food, recreation and clothing with the spatial and ecological 21 March, 2019 frame in mind. So, there is nothing innate about ethnicity, ethnic differences are wholly learned through __________________ the process of socialization where people assimilate with the lifestyles, norms, beliefs of their Key Words communities. The Chinese community of Kolkata which group possesses a clearly defined spatial segmentation in the city. They have established unique modes of identity in landscape, culture, Ethnicity economic and inter-societal relations. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Landscaping India: from Colony to Postcolony

Syracuse University SURFACE English - Dissertations College of Arts and Sciences 8-2013 Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony Sandeep Banerjee Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Geography Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sandeep, "Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony" (2013). English - Dissertations. 65. https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd/65 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in English - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT Landscaping India investigates the use of landscapes in colonial and anti-colonial representations of India from the mid-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries. It examines literary and cultural texts in addition to, and along with, “non-literary” documents such as departmental and census reports published by the British Indian government, popular geography texts and text-books, travel guides, private journals, and newspaper reportage to develop a wider interpretative context for literary and cultural analysis of colonialism in South Asia. Drawing of materialist theorizations of “landscape” developed in the disciplines of geography, literary and cultural studies, and art history, Landscaping India examines the colonial landscape as a product of colonial hegemony, as well as a process of constructing, maintaining and challenging it. In so doing, it illuminates the conditions of possibility for, and the historico-geographical processes that structure, the production of the Indian nation. -

A Hundred Years of Tagore in Finland

Cracow Indological Studies vol. XVII (2015) 10.12797/CIS.17.2015.17.08 Klaus Karttunen [email protected] (University of Helsinki) A Hundred Years of Tagore in Finland Summary: The reception of Rabindranath Tagore in Finland, starting from newspa- per articles in 1913. Finnish translations of his works (19 volumes in 1913–2013, some in several editions) listed and commented upon. Tagore’s plays in theatre, radio and TV, music composed on Tagore’s poems. Tagore’s poem (Apaghat 1929) commenting upon the Finnish Winter War. KEYWORDS: Rabindranath Tagore, Bengali Literature, Indian English Literature, Fin nish Literature. In Finland as well as elsewhere in the West, the knowledge of Indian literature was restricted to a few Sanskrit classics until the second decade of the 20th century. The Nobel Prize in Literature given to Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) in 1913 changed this at once. To some extent, the importance of Tagore had been noted even before—the Swedish Nobel Committee did not get his name out of nowhere.1 Tagore belonged to a renowned Bengali family and some echoes of this family had even been heard in Finland. As early as the 1840s, 1 The first version of this paper was read at the International Tagore Conference in Halle (Saale), Germany, August 2–3, 2012. My sincere thanks are due to Hannele Pohjanmies, the translator of Tagore’s poetry, who has also traced many details about the history of the poet in Finland. With her kind permission, I have used this material, supplementing it from newspaper archives and from my own knowledge. -

Professor Dr. Abdul Momin Chowdhury Email: [email protected]

Professor Dr. Abdul Momin Chowdhury email: [email protected] Present Position: Fellow Asiatic Society of Bangladesh Project Director History of Bangladesh: Ancient and Medieval Asiatic Society of Bangladesh Fulbright Senior Research Fellow Department of History Vanderbilt University Nashville, Tennessee USA Adjunct Faculty, School of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, Independent University, Bangladesh Current Research Projects: 1. History of Bangladesh: Ancient and Medieval 2. Identity/Alterity: Bangladesh Perspective Academic Awards: State Overseas Scholarship, 1962-1965 Commonwealth Academic Staff Fellowship, 1975-1976, for post-Doctoral Research at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Commonwealth Senior Visiting Fellowship, 1988, visited several universities in India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Singapore, Malaysia and Australia to make on the spot study of Academic administration. British Council Short Term Fellowship, 1985, visited several universities in the U.K. to see the administration of the Libraries. U.S. IVP, 1985, visited several universities in the U.S.A. to observe the academic administration of Universities. Visiting Lecturer, Heidelberg University, Germany, 1985. South Asia Dialogue Fellowship, 1992, for research in the field of Democratisation in South Asia. Short Term Fellowship, Indian Council of Historical Research, 1996. Represented Bangladesh at the Inter-Governmental meeting on the Convention on Intangible Cultural Heritage at UNESCO, Paris in September, 2002 and February, 2003. Fullbright