Hunger, Consumption, and Identity in Elizabeth Gaskell's Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preservation and Progress in Cranford

Preservation and Progress in Cranford Katherine Leigh Anderson Lund University Department of English ENGK01 Bachelor Level Degree Essay Christina Lupton May 2009 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction and Thesis.................................................. 3 II. Rejection of Radical Change in Cranford...................... 4 III. Traditional Modes of Progress....................................... 11 IV. Historical Transmission Through Literature.................. 14 V. Concluding Remarks....................................................... 18 VI. Works Cited...................................................................... 20 2 Introduction and Thesis Elizabeth Gaskell's Cranford was first published between 1851 and 1853 as a series of episodic stories in Household Words under the the editorship of Charles Dickens; it wasn't until later that Cranford was published in single volume book form. Essentially, Cranford is a collection of stories about a group of elderly single Victorian ladies and the society in which they live. As described in its opening sentence, ”In the first place, Cranford is in possession of the Amazons; all the holders of houses, above certain rent, are women” (1). Cranford is portrayed through the eyes of the first person narrator, Mary Smith, an unmarried woman from Drumble who visits Cranford occasionally to stay with the Misses Deborah and Matilda Jenkyns. Through Mary's observations the reader becomes acquainted with society at Cranford as well as Cranfordian tradition and ways of life. Gaskell's creation of Cranford was based on her own experiences growing up in the small English town of Knutsford. She made two attempts previous to Cranford to document small town life based on her Knutsford experiences: the first a nonfiction piece titled ”The Last Generation” (1849) that captured her personal memories in a kind of historical preservation, the second was a fictional piece,”Mr. -

N混WS1LJE うrtje

現邸主 MEETING OF 強 E GASKELL SOCIETY WILL BE lN MAN C'昆 EST 限必 84 乱, YMOUT 聾 GROVE Date: Date: APRIL 26TH T1 箇e: 2. ∞p ・乱 CMmRMpueba4J ke ec 世&+』 ---e ふ GEOF 路島Y SI 強RPS を t1AMW HO 官 1 BECAME A GASKELLIA 琵 付wm T錦町 主1.00 叩川町 UHH 品世:ミ RSVP: MRS J 脅 LEAC 日- Tel: 0565 4;:¥ 五8 Jt , 、:J C, iγγCCNず~t. 島民.00 鉱 ST. 続 IAP&L 制吋 揺蹄.G 制加語、 G師協 PIAN 守1:) F.N>> p、 "~o U1" H CHESHU 2.[ ミ G 時:T VE. 混 う J& ふ N WS 1L JE rTJE Comment8 , contributioDS and suggestions welcomed by the 恕X 宝OR: Mrs J. Lea ch , Far Yew Tree .House , OVer OVer Tabley ,Knutsford ,Che~hire 砥晶 16 鑑賞 離 AllC 麗 19.' NO.I Telephone: Telephone: 0565 4668 EDITCR'S LETTER 工 have only 工'ecent 工y realised hoVJ many literarγsocieties there are and what exce 工工 ent 工iterature many of them produce~ so 工 am rather nervous about venturing into print as editor of this ,the first Gaskel 工 Society Newsletter 。 The B~cntg Society was founded in 1893 so 工 am sure that their first pub 工ications must now be co 工工 ectors' itemso Our two Societies share a common interest through tt. e 、寸 friendship of Elizabeth Gaskell and Charlotte Bron 七話; in the current Brontg Socie 七y Transactions Mrs Gaskell's name appears on a third of 七he pages 。 As members of The GB_skell Society we have some missionary work to do ,to win better recognition for Eユizabeth Gaske 工工 's varied achievemen 七S 。 工t is encouragins to note that her novels are now available in several paper-back series: OaUaPo ,Penguin and Den 七。 工was appal 工ed by the inaccuracy of Longman's Outline of English Literature entry for Elizabeth Gaske ユエ which 工 -

Gaskell Society Newsletter Contents

GASKELL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER CONTENTS No.1. March 1986. Nussey, John. Inauguration of the Gaskell Society: a Brontë Society Members’ Account. p3-5. Brill, Barbara. Annie A. and Fleeming [Jenkin]. p6-11. [Leach, Joan]. Mrs Gaskell – a Cinderella at Chatsworth. p14-16. No.2. August 1986. Brill, Barbara. Job Legh and the working class naturalists. p3-6. [Keaveney, Jennifer]. Mastermind. p6. Kirkland, Janice. Mrs Gaskell’s country houses, [Boughton House, Worcester; Hulme Walfield, Congleton; The Park, near Manchester]. p10-11. Leach, Joan. Mrs Gaskell’s Cheshire; Summer Outing – June 29th 1986, [Tabley House & chapel. The Mount, Bollington]. [illus.] p12-19. Monnington, Rod. Where can I find Mrs Gaskell? [The Diary of a Hay on Wye Bookseller, by Keith Gowen, 1985]. p23-24. No.3. Spring 1987. Hewerdine, H., F.R.S.H. Cross Street Chapel. p3-5. Marroni, Francesco. Elizabeth Gaskell in Italian translation. p6-8. Leach, Joan. Cleghorn. p9-10. Moon, Richard. Letter on Boughton Park, [Worcester]. p14. Leach, Joan. Thomas Wright, the Good Samaritan [by G.F. Watts]. [illus.] p15-25. No.4. August 1987. Thwaite, Mary. The “Whitfield” Gaskell collection, [Knutsford Library]. p3-5. Brill, Barbara. William Gaskell’s hymns. p6-8. [Leach, Joan]. Green Heys Fields, [Manchester]. [Country rambles and wild flowers by Leo Grindon, 1858]. p11-12. [Heathwaite House, Knutsford]. [illus. of 1832 water colour]. p13. Summer outing to North Wales, [Sunday June 29th 1987]. [gen. table]. p14-21. [Lascelles, Gen. Sir Alan]. A Cranford fan. p23. [Leach, Joan]. The Gaskells and poetry. p24. No.5. March 1988. Jacobi, Elizabeth (later Rye). Mrs. Gaskell, [port. by H.L. -

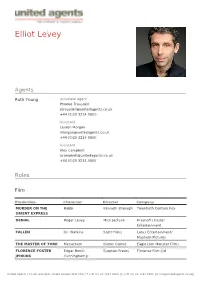

Elliot Levey

Elliot Levey Agents Ruth Young Associate Agent Phoebe Trousdell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Lauren Morgan [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Alex Campbell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company MURDER ON THE Rabbi Kenneth Branagh Twentieth Century Fox ORIENT EXPRESS DENIAL Roger Levey Mick Jackson Krasnoff / Foster Entertainment FALLEN Dr. Watkins Scott Hicks Lotus Entertainment/ Mayhem Pictures THE MASTER OF YORK Menachem Kieron Quirke Eagle Lion Monster Films FLORENCE FOSTER Edgar Booth Stephen Frears Florence Film Ltd JENKINS Cunningham Jr United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE LADY IN THE VAN Director Nicholas Hytner Van Production Ltd. SPOOKS Philip Emmerson Bharat Nalluri Shine Pictures & Kudos PHILOMENA Alex Stephen Frears Lost Child Limited THE WALL Stephen Cam Christiansen National film Board of Canada THE QUEEN Stephen Frears Granada FILTH AND WISDOM Madonna HSI London SONG OF SONGS Isaac Josh Appignanesi AN HOUR IN PARADISE Benjamin Jan Schutte BOOK OF JOHN Nathanael Philip Saville DOMINOES Ben Mirko Seculic JUDAS AND JESUS Eliakim Charles Carner Paramount QUEUES AND PEE Ben Despina Catselli Pinhead Films JASON AND THE Canthus Nick Willing Hallmark ARGONAUTS JESUS Tax Collector Roger Young Andromeda Prods DENIAL Roger Levey Denial LTD Television Production Character Director Company -

Elizabeth Gaskell and the Middle Class

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2009 “The Sort . of People to Which I Belong”: Elizabeth Gaskell and the Middle Class Allison Masters The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Masters, Allison, "“The Sort . of People to Which I Belong”: Elizabeth Gaskell and the Middle Class" (2009). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 16. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/16 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE SORT . OF PEOPLE TO WHICH I BELONG”: ELIZABETH GASKELL AND THE MIDDLE CLASS By ALLISON JEAN MASTERS B.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, 2006 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in English Literature The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2009 Approved by: Perry Brown, Associate Provost for Graduate Education Graduate School John Glendening, Chair English Jill Bergman English Ione Crummy French Masters ii Masters, Allison, M.A., May 2009 English “The Sort . of People to Which I Belong”: Elizabeth Gaskell and the Middle Class Chairperson: John Glendening In this thesis, I examine Elizabeth Gaskell’s development as a middle-class author, which is a position that most scholars take for granted. -

Official Town Guide 2019-21

FREE KNUTSFORD OFFICIAL TOWN GUIDE 2019-21 DISCOVER • ENJOY • EXPLORE EEL Knutsford Town Guide Ad2 2019.qxp_A5 14/03/2019 18:10 Page 1 Back to the future boarding.pdf 1 17/01/2019 08:14 The UK’s market leading supplier of electrical products to trade and industry. C 2019 M SEP Y CM MY CY CMY B0B0 ARDARD 1NG1NGk K 77 days daysdaysdadaysys per per peperpper weekrweekweeweek weekweweekek o.uk • Over 350 branches nationwide • Over 120,000 unique items in stock ssignsignign uupupp a ataatt [email protected]@[email protected] .u • Same day delivery service • Professional, friendly and expert advice Terra Nova School in Holmes Chapel now Edmundson Electrical Ltd offers day, flexi and full boarding for pupils. Tatton Street • Knutsford • Cheshire • WA16 6AY Tel: 01565 700100 • Fax: 01565 652649 www.edmundson-electrical.co.uk Date: 23.01.19 Proof level: Acc. Ref: 200194 1 Proof level: Date: 27.03.19 Publication: KNUTSFORD TG 2019 APPROVED 1Size: FLL BLEED* 148mm w x 210mm h Acc. Ref: 200196 AMENDMENTS Position: Facing Inside Front cover REQUIRED Publication: KNUTSFORD TG 2019 Please check this proof carefully APPROVED Size: Full page - trim 148 x 210mm We make every eort to ensure that your proofs are correct. It is your responsibility to ensure errors are spotted before publication. Examples of items your should check are contact details, spelling, grammar, design and layout. AMENDMENTS Inside front cover PDF proofs are for content verication only. Images have been downsampled to allow for transmission via email. PDF proofs are not to be considered as Position: REQUIRED colour-accurate, even on colour-managed screens. -

From Cranford to the Country of the Pointed Firs: Elizabeth Gaskell's American Publication and the Work

From Cranford to The Country of the Pointed Firs: Elizabeth Gaskell’s American Publication and the Work of Sarah Orne Jewetti ALAN SHELSTON In this second of two articles on Elizabeth Gaskell’s American connections I plan first to outline the history of the publication of her work in the United States during her own lifetime, and then to consider the popularity of Cranford in that country in the years following her death. I shall conclude by discussing the work of the New England writer, Sarah Orne Jewett whose story sequences Deephaven (1877) and The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896) clearly reflect the influence of Gaskell’s work. I One of the remarkable things about Gaskell’s career as a novelist is the way in which, after a late start, her career took off. She was in her late thirties when Mary Barton was published, but from then on, and in particular through the 1850s, her output was incessant. This was partly due to the fact that Dickens took her up for Household Words; it is interesting to watch her becoming increasingly independent of his encouragement and influence through the fifties decade. What is also interesting is the extent to which she was taken up abroad, both on the continent and in the USA. To some extent this is because publishers in those countries found it more profitable to publish established English authors - even if, as in the case of the Europeans, they had to translate them - than to develop native talent. It was a period when popular fiction flourished, often published in cheap and sometimes unauthorised popular series. -

Irma Inniss Producer

Irma Inniss Producer Irma is currently producing the third season of THE BAY for Tall Story Pictures and ITV. Prior to that she was Development Producer on a freelance basis at Ged Doherty and Colin Firth's company Raindog Films. Irma is a highly experienced Actor, Dramaturg, Script Executive and Producer who was recently script exec'ing series three of Kudos' TIN STAR. Prior to this she spent two years as Producer on BBC continuing drama series HOLBY CITY, having script edited HOLBY CITY and EASTENDERS. Irma has produced over 30 hours of television, including the critically –acclaimed “Man Down” a HOLBY CITY episode which highlighted the plight of a much-loved, regular character, in denial about his chronic depression and in crisis. She was a dramaturg on INSIDE OUT a play, by Tanika Gupta, produced by Clean Break and for LISTEN TO YOUR PARENTS by Benjamin Zephaniah, originally commissioned and transmitted on Radio 4. The play was reworked for a touring theatre production, before running at The Lyric, Hammersmith. As an actor, Irma has worked extensively, in theatre, television, radio and film; most often in new plays including WELCOME TO THEBES, written by Moira Buffini and directed by Richard Eyre, at the Olivier, for the National Theatre; DAUGHTERS at the Royal Court Theatre, directed by Ramin Gray; award-winning APACHE TEARS for Clean Break Theatre Company, at the Battersea Arts Centre and the THE WIDE SARGASSO SEA, adapted by Rukhsana Ahmad, for Radio 4. Television and film includes SILENT WITNESS, DESMOND’S, CORONATION STREET and the multi award-winning short film, PERFECT IMAGE?. -

AND ELIZABETH GASKELL's CRANFORD by Meryem A. Udden

Playacting happiness: tragicomedy in Jane Austen's Mansfield Park and Elizabeth Gaskell's Cranford Item Type Thesis Authors Udden, Meryem A. Download date 01/10/2021 08:14:04 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/11295 PLAYACTING HAPPINESS: TRAGICOMEDY IN JANE AUSTEN'S MANSFIELD PARK AND ELIZABETH GASKELL'S CRANFORD By Meryem A. Udden, B.A. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English University of Alaska Fairbanks May 2020 APPROVED: Rich Carr, Committee Chair Eric Heyne, Committee Member Terence Reilly, Committee Member Rich Carr, Department Chair Department of English Todd Sherman, Dean College of Liberal Arts Michael Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School Abstract This thesis examines tragicomedy in two 19th Century British novels, Jane Austen's Mansfield Park and Elizabeth Gaskell's Cranford. Both narratives have perceived happy endings; however, tragedy lies underneath the surface. With Shakespeare's play A Midsummer Night's Dream as a starting point, playacting becomes the vehicle through which tragedy can be discovered by the reader. Throughout, I find examples in which playacting begins as a comedic act, but acquires tragic potential when parents enter the scene. Here, I define tragedy not as a dramatic experience, but rather seemingly small injustices that, over time, cause more harm than good. In Mansfield Park, the tragedy is parental neglect and control. In Cranford, the tragedy is parental abuse. For both narratives, characters are unable to experience life fully, and past parental injuries cannot be redeemed. While all the children in the narratives experience some form of parental neglect, the marginalized children are harmed more than the others. -

What Kind of Book Isc( Cr Anfora"?

What Kind of Book is C( Cr anfora"? GEORGE V. GRIFFITH "That a book is a novel means anything or nothing; the practical question relates to its character and contents."1 -LOR SO SLIGHT a thing Cranford is a problematic book. Every• one loves it, although no one is quite sure how it works or what it is. A glance at its printing history and the history of its critical reception confirms the problem. Whereas Mrs. GaskelPs other novels have seen no more than five or six editions, Cranford has appeared in no fewer than one hundred and seventy editions since 1853.2 Yet through the critical assessment and revaluation two troubling questions persist. The first is a generic question (is it a novel?), the second a question of narrative technique (what is the manner of its telling?). Cranford has been alternately labelled a novel or a collection of sketches. Generic labellers have consistently hedged, carefully tendering their descriptions with oddly hyphenated terms and a liberal sprinkling of the words "although" and "perhaps." Thus to a biographer what begins as a "story-article" became what "might be called a novel."3 To an eminent historian of the novel Cranford "happily perhaps is not a novel."* To a chronicler of the short story form Cranford "though it has far more unity than a mere collection of stories about a single locale, is after all episodic and more truly belongs to the history of short fiction than some of her shorter pieces."5 A similar confusion characterizes the discussion of Cranford's narrative technique. -

CRANFORD & the CAGE at CRANFORD by ELIZABETH

CRANFORD & THE CAGE AT CRANFORD by ELIZABETH GASKELL 01 - Preface 36:24 02 - Ch. 1 Our Society 26:08 03 - Ch. 2 The Captain 36:10 04 - Ch. 3 A Love Affair of Long Ago 22:30 05 - Ch. 4 A Visit to an Old Bachelor 27:22 06 - Ch. 5 Old Letters 27:45 07 - Ch. 6 Poor Peter 29:44 08 - Ch. 7 Visiting 25:15 09 - Ch. 8 Your Ladyship 32:37 10 - Ch. 9 Signor Brunoni 24:56 11 - Ch. 10 The Panic 35:10 12 - Ch. 11 Samuel Brown 28:43 13 - Ch. 12 Engaged to Be Married 21:06 14 - Ch. 13 Stopped Payment 30:21 15 - Ch. 14 Friends in Need 45:50 16 - Ch. 15 A Happy Return 34:03 17 - Ch. 16 Peace to Cranford 20:37 18 - The Cage at Cranford 30:13 Cranford & The Cage At Cranford At Cranford & The Cage Cranford is set in a small market town populated largely by a number of respectable ladies. It tells of their secrets and foibles, their gossip and their romances as they face the challenges of dealing with new inhabitants to their society and innovations to their settled existence. It was first published between 1851 and 1853 as episodes in Charles Dickens’ Journal Household Words. Appended to this recording is a short sequel, The Cage at Cranford, written ten years beth Gaskell beth All the Year Round later and published in the journal . Eliza In a letter to Mrs. Gaskell, Charlotte Bronte wrote: “Thank you for your letter, it was as pleasant as a quiet chat, as welcome as spring showers, as reviving as a friend’s visit; Cranford in short, it was very like a page of .”.. -

Taste and Morality at Plymouth Grove: Elizabeth Gaskell's Home and Its

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Lincoln Institutional Repository Taste and Morality at Plymouth Grove: Elizabeth Gaskell’s Home and its Decoration E JIM CHESHIRE AND MICHAEL CRICK SMITH Abstract: In 2010 Manchester Historic Buildings Trust appointed Crick Smith Conservation to analyse the paint and decorative finishes of the Gaskell’s House at 84 Plymouth Grove, Ardwick, Manchester. The purpose of this commission was to inform the Trust of the way that decorative surfaces were treated during the period of the Gaskell family occupancy and to make recommendations for the reinstate- ment of the decorative scheme. This article will examine Elizabeth Gaskell’s attitude towards taste and interior decoration and then explain how the techniques of architectural paint research can be used to establish an authoritative account of the decorative scheme implemented at Plymouth Grove during her lifetime. We will argue that this enhanced understanding of how Gaskell handled the decora- tion and furnishing of her home can contribute towards our understanding of the author’s life and work. One of my mes is, I do believe, a true Christian – (only people call her socialist and communist), another of my mes is a wife and mother, and highly delighted at the delight of everyone else in the house […]. Now that’s my ‘social’ self I suppose. Then again I’ve another self with a full taste for beauty and convenience whh is pleased on its own account. How am I to reconcile all these warring members? (Letters, p.