The Continuing Depression. By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE P

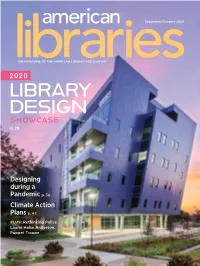

September/October 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 2020 LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE p. 28 Designing during a Pandemic p. 36 Climate Action Plans p. 42 PLUS: Rethinking Police, Laurie Halse Anderson, Puppet Troupe PLA 2020 VIRTUAL STREAM NOW ON-DEMAND Educational programs from the PLA 2020 Virtual Conference are now available on-demand*, including: Bringing Technology and Arts Programming to Senior Adults Creating a Diverse, Patron-Driven Collection Decreasing Barriers to Library Use Going Fearlessly Fine-Free Intentional Inclusion: Disrupting Middle Class Bias in Library Programming Leading from the Middle Part Playground, Part Laboratory: Building New Ideas at Your Library Programming for All Abilities Training Staff to Serve Patrons Experiencing Homelessness in the Suburbs We're All Tech Librarians Now Cost: for PLA members for Nonmembers for Groups *Programs are sold separately. www.ala.org/pla/education/onlinelearning/pla2020/ondemand September/October 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #9/10 | ISSN 0002-9769 2020 LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE The year’s most impressive new and renovated spaces | p. 28 BY Phil Morehart 22 FEATURES 22 2020 ALA Award Winners Honoring excellence and 42 leadership in the profession 36 Virus-Responsive Design In the age of COVID-19, architects merge future-facing innovations with present-day needs BY Lara Ewen 50 42 Ready for Action As cities undertake climate action plans, libraries emerge as partners BY Mark Lawton 46 Rethinking Police Presence Libraries consider divesting from law enforcement BY Cass Balzer 50 Encoding Space Shaping learning environments that unlock human potential BY Brian Mathews and Leigh Ann Soistmann ON THE COVER: Library Learning Center at Texas Southern University in Houston. -

Downloading—Marquee and the More You Teach Copyright, the More Students Will Punishment Typically Does Not Have a Deterrent Effect

June 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION COPING in the Time of COVID-19 p. 20 Sanitizing Collections p. 10 Rainbow Round Table at 50 p. 26 PLUS: Stacey Abrams, Future Library Trends, 3D-Printing PPE Thank you for keeping us connected even when we’re apart. Libraries have always been places where communities connect. During the COVID19 pandemic, we’re seeing library workers excel in supporting this mission, even as we stay physically apart to keep the people in our communities healthy and safe. Libraries are 3D-printing masks and face shields. They’re hosting virtual storytimes, cultural events, and exhibitions. They’re doing more virtual reference than ever before and inding new ways to deliver additional e-resources. And through this di icult time, library workers are staying positive while holding the line as vital providers of factual sources for health information and news. OCLC is proud to support libraries in these e orts. Together, we’re inding new ways to serve our communities. For more information and resources about providing remote access to your collections, optimizing OCLC services, and how to connect and collaborate with other libraries during this crisis, visit: oc.lc/covid19-info June 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #6 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 20 Coping in the Time of COVID-19 Librarians and health professionals discuss experiences and best practices 42 26 The Rainbow’s Arc ALA’s Rainbow Round Table celebrates 50 years of pride BY Anne Ford 32 What the Future Holds Library thinkers on the 38 most -

College and Research Libraries

ROBERT B. DOWNS The Role of the Academic Librarian, 1876-1976 . ,- ..0., IT IS DIFFICULT for university librarians they were members of the teaching fac in 1976, with their multi-million volume ulty. The ordinary practice was to list collections, staffs in the hundreds, bud librarians with registrars, museum cu gets in millions of dollars, and monu rators, and other miscellaneous officers. mental buildings, to conceive of the Combination appointments were com minuscule beginnings of academic li mon, e.g., the librarian of the Univer braries a centur-y ago. Only two univer sity of California was a professor of sity libraries in the nation, Harvard and English; at Princeton the librarian was Yale, held collections in ·excess of professor of Greek, and the assistant li 100,000 volumes, and no state university brarian was tutor in Greek; at Iowa possessed as many as 30,000 volumes. State University the librarian doubled As Edward Holley discovered in the as professor of Latin; and at the Uni preparation of the first article in the versity of · Minnesota the librarian present centennial series, professional li served also as president. brarHms to maintain, service, and devel Further examination of university op these extremely limited holdings catalogs for the last quarter of the nine were in similarly short supply.1 General teenth century, where no teaching duties ly, the library staff was a one-man opera were assigned to the librarian, indicates tion-often not even on a full-time ba that there was a feeling, at least in some sis. Faculty members assigned to super institutions, that head librarians ought vise the library were also expected to to be grouped with the faculty. -

LHRT Newsletter LHRT Newsletter

LHRT Newsletter NOVEMBER 2010 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 1 BERNADETTE A. LEAR, EDITOR BAL19 @ PSU.EDU Greetings from the Chair BAL19 @ PSU.EDU and librarians. The week As we finalize details we will following Library History inform the membership as to Seminar XII, Wayne how they may participate. Wiegand threw down a challenge. He offered to It is time to turn to finding a contribute $100 to the venue for Library History Edward G. Holley Lecture Seminar XIII (2015). The endowment, and urged all request for proposals is previous LHRT Chairs and included in this newsletter. I Board members to do the invite LHRT members to same. In less than thirty- consider whether your six hours $2,400 was institution might be a good pledged. Ed’s son Jens was site. We are a community of one contributor (both to people with a love for the the fund and to this issue). histories of libraries, reading, His heartfelt message of print culture, and the people, thanks for honoring his places and institutions that are father in this way made me part of those histories. Why proud to be a member of not make a little bit of history LHRT. yourself by hosting this wonderful conference? The LHRT Program Committee is hard at work In the meantime, I will “see” to bring quality sessions to you virtually in January our annual meeting. We meeting in cyberspace, and see will have the Invited many of you in person at Speakers Panel, the ALA’s annual meeting in New Research Forum Panel, and Orleans in June. -

The Newberry Annual Report 2016 – 17

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2016 – 17 Letter from the Chair and the President hat a big and exciting year the Newberry had in 2016-17! As Wan institution, we have been very much on the move, and on behalf of the Board of Trustees and Staff we are delighted to offer you this summary of the destinations we reached last year and our plans for moving forward in 2017-18. Financially, the Newberry enjoyed much success in the past year. Excellent performance by the institution’s investments, up 13.2 percent overall, put us well ahead of the performance of such bellwether endowments as those of Harvard and Yale. Our drawdown on investments for operating expenses was a modest 3.8 percent, well Chair of the Board of Trustees Victoria J. Herget and below the traditional target of 5.0 percent. In fact, of total operating Newberry President David Spadafora expenses only 22.9 percent had to be funded through spending from the endowment—a reduction by more than half of our level of reliance on endowment a decade ago. Partly this change has resulted from improvement in Annual Fund giving: in 2016-17 we achieved the greatest-ever single- year tally of new gifts for unrestricted operating expenses, $1.75 million, some 42 percent higher than just before the economic crisis 10 years ago. Funding for restricted purposes also grew last year, with generous gifts from foundations and individuals for specific programs and projects. Partly, too, our good financial results are owing to continued judicious control of expenses, exemplified by the fact that total staffing levels were 2.7 percent lower in 2016-17 than in 2006-07. -

A New Era for Museums”: Professionalism and Ideology in the American Association of Museums, 1906-1935

Wesleyan University The Honors College “A New Era for Museums”: Professionalism and Ideology in the American Association of Museums, 1906-1935 by Hannah Freece Class of 2009 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in History Middletown, Connecticut April, 2009 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter 1: Precedents 15 Chapter 2: Founding 31 Chapter 3: Philosophy 45 Chapter 4: Practice 70 Conclusion 96 Bibliography 101 2 Acknowledgements I must first extend my gratitude to my thesis advisor, Kirk Swinehart, and second reader, Elizabeth Milroy, for their encouragement, suggestions, and support this year. They were both exceedingly helpful and a pleasure to work with. At Wesleyan, I also thank Abby Clouse, Patricia Hill, Nancy Noble, Clare Rogan, Ron Schatz, and Joseph Siry and for their input at various stages of this project. I am grateful to the Davenport Study Grant Committee for providing the funds that enabled me to begin my research in the summer of 2008 in Washington, D.C. David Ward and Martin Sullivan at the National Portrait Gallery graciously fielded my questions about museum history. At the American Association of Museums, Jill Connors-Joyner and Susan Breitkopf supported my interests and questions from my first days as an intern there. I also thank the librarians and archivists who assisted me, including Mary Markey at the Smithsonian Institution Archives and Doris Sherrow- Heidenis and Alan Nathanson at Olin Library. Finally, I thank my friends and family for their humor, understanding, patience, and champion proofreading. -

2019 ALA Impact Report

FIND THE LIBRARY AT YOUR PLACE 2019 IMPACT REPORT THIS REPORT HIGHLIGHTS ALA’S 2019 FISCAL YEAR, which ended August 31, 2019. In order to provide an up-to-date picture of the Association, it also includes information on major initiatives and, where available, updated data through spring 2020. MISSION The mission of the American Library Association is to provide leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. MEMBERSHIP ALA has more than 58,000 members, including librarians, library workers, library trustees, and other interested people from every state and many nations. The Association services public, state, school, and academic libraries, as well as special libraries for people working in government, commerce and industry, the arts, and the armed services, or in hospitals, prisons, and other institutions. Dear Colleagues and Friends, 2019 brought the seeds of change to the American Library Association as it looked for new headquarters, searched for an executive director, and deeply examined how it can better serve its members and the public. We are excited to give you a glimpse into this momentous year for ALA as we continue to work at being a leading voice for information access, equity and inclusion, and social justice within the profession and in the broader world. In this Impact Report, you will find highlights from 2019, including updates on activities related to ALA’s Strategic Directions: • Advocacy • Information Policy • Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion • Professional & Leadership Development We are excited to share stories about our national campaigns and conferences, the expansion of our digital footprint, and the success of our work to #FundLibraries. -

The Newberry Annual Report 2019–20

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2019–20 30 Fall/Winter 2020 Letter from the Chair and the President Dear Friends and Supporters of the Newberry, The Newberry’s 133rd year began with sweeping changes in library leadership when Daniel Greene was appointed President and Librarian in August 2019. The year concluded in the midst of a global pandemic which mandated the closure of our building. As the Newberry staff adjusted to the abrupt change of working from home in mid-March, we quickly found innovative ways to continue engaging with our many audiences while making Chair of the Board of Trustees President and Librarian plans to safely reopen the building. The Newberry David C. Hilliard Daniel Greene responded both to the pandemic and to the civil unrest in Chicago and nationwide with creativity, energy, and dedication to advancing the library’s mission in a changed world. Our work at the Newberry relies on gathering people together to think deeply about the humanities. Our community—including readers, scholars, students, exhibition visitors, program attendees, volunteers, and donors—brings the library’s collection to life through research and collaboration. After in-person gatherings became impossible, we joined together in new ways, connecting with our community online. Our popular Adult Education Seminars, for example, offered a full array of classes over Zoom this summer, and our public programs also went online. In both cases, attendance skyrocketed, and we were able to significantly expand our geographic reach. With the Reading Rooms closed, library staff responded to more than 450 research questions over email while working from home. -

Articles on Library Instruction in Colleges and Universities, 1876-1932

I LLJNOI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. ~p· University of Illinois p ' GraduateSchool of Library Science ,P'E R 5-' F--- --- q o ISSN 0073 5310 Number 143 February 1980 Articles on Library Instruction in Colleges and Universities, 1876 - 1932 by John Mark Tucker THE UamSR oa IMB %.4 2 41990 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS URBANA-CHAMPAIGN I , Xlqo Contents A bstract ..................................... ........ .. 3....3 Introduction .................................................. .3 Bibliography ................................................... 7 Author Index ................................................ 38 Institution Index ............................................... 39 Vita ............................................................. 45 o q ABSTRACT Emphasizing journal literature from 1976 to 1932, this compilation anno- tates articles about library instruction in colleges, universities, and schools of teacher education in the United States. It provides access to secondary materials for historians and librarians interested in academic library devel- opment and, more specifically, the origins and growth of library instruc- tion. Entries were chosen using the five specifications for bibliographic instruments identified by Patrick Wilson in Two Kinds of Power;An Essay on BibliographicalControl. The years selected for inclusion complement the various published bibliographies devoted to current practice. INTRODUCTION -

IDEALS @ Illinois

ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Librarv/ Trends VOLUME 17 NUMBER 4 APRIL, 1969 The Changing Nature of the School Library MAE GRAHAM Issue Editor CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE MAE GRAHAM 343 Introduction B. LUCILE BOWIE , 345 Changing Perspective; in Educaiional Goals 'and Knowlkdge ' of the Learner ALBERT H. NAENY . 355 Changing Patterns in School Curriculum and Organization MARVIN R. A. JOHNSON 362 Facilities and Standbds * GAYLEN B. KELLEY * 374 Technological Advanles Affecting Schdol Inskuctional Materials Centers LWRA E. CRAWFORD . 383 The Changing Nature of Sihool Libra& Coll'ection's HELEN F. RICE 401 Changing Staff * Pattems aid Responsibilities' MARGARET HAYES GRAZIER . 410 Effects of Change on Education 'for Sdhool Librarians * JOHN MACKENZIE CORY 424 Changing Patterns of' Public Library aid Sdhool Librar; Rela tionships This Page Intentionally Left Blank Introduction MAE GRAHAM THEREWAS A TIME when it was fashionable to present to a young woman on her eighteenth birthday a china or copper plate on which was hand painted or etched the following couplet: Standing with reluctant feet Where the brook and river meet. It is the opinion of the editor of this issue of Library Trends that school libraries have now reached this enviable transition stage. There are healthy signs. A marriage has been arranged, represented by the 1969 Standards for School Media Programs prepared jointly by the American Association of School Librarians (ALA) and the Depart- ment of Audio-visual Instruction (NEA). Traditionally, marriages of convenience are arranged for purposes of consolidating and thereby increasing wealth, influence, and prestige and to produce a stronger dynasty. -

" Referred to the Librarian, with Power to Act": Herbert Putnam and The

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 708 IR 058 202 AUTHOR Aikin, Jane TITLE "Referred to the Librarian, with Power To Act": Herbert Putnam and the Boston Public Library. PUB DATE 2001-08-00 NOTE 9p.; In: Libraries and Librarians: Making a Difference in the Knowledge Age. Council and General Conference: . Conference Programme and Proceedings (67th, Boston, MA, August 16-25, 2001); see IR 058 199. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.ifla.org. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) -- Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biographies; *Librarians; *Library Development; *Library Directors; Library Services; *Public Libraries IDENTIFIERS Boston Public Library MA ABSTRACT Herbert Putnam was Librarian of the Boston Public Library between February 1895 and April 1899, the first experienced librarian to hold that post since Charles Coffin Jewett (1855-68) .This paper reviews the circumstances surrounding his appointment and discusses his accomplishments, including expansion of the library system, services for scholars, services to the schools, the addition of new departments, and a new staff classification and promotion system. The physical problems of the library's new building and the resulting renovation are also addressed. (Contains 32 endnotes.) (Author/MES) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. 67th IFLA Council and General Conference August 16-25, 2001 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS CENTER (ERIC) BEEN GRANTED BY A Thisdocument has been reproduced as Code Number: 010-149-E received from the person or organization Division Number: VII originating it. -

Library Buildings

Library Buildings WALTER C. ALLEN AMONGTHE MORE visible changes in the library field during the past one hundred years is the development of the library building-its appearance, arrangement, structure, equipment, and atmosphere. Not only are there many more buildings, they are immensely more complex, varied, and sophisticated. Just as all library materials and services have evolved into new forms and techniques, so have buildings changed to reflect and encourage these new responses to the needs of the various communities and subcommunities which make up our nation. It is the purpose of this paper to examine a century of library architecture in relation to the changing perceptions of library functions, the development of building techniques and materials, fluctuating aesthetic fashions and sometimes wildly erratic economic climates. In an arbitrary fashion which may annoy some, I have divided the century into several periods of unequal length. Naturally, there were exceptions to patterns, and I shall attempt to note the most important (or egregious) of these. First, there will be a description of the scene in 1876, followed by a summary of the developments until 1892, a period which can only be called “floundering.” Next will be a larger section on the “monumental,” from 1893 to 1950, with a subsection on 1939-50, which might be called the “dawn.” The period 1950-76 has already been called a “golden age,” certainly in terms of quantity if not always of quality. I prefer to think of it as simply “the modern,” for while we have made many advances during the past twenty-five years, we may not have yet reached full maturity.