INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit Birmingham, Gatwick, Glasgow, Heathrow, Luton, Manchester, Stansted Full and Summary Analysis August 1995 Disclaimer The information contained in this report will be compiled from various sources and it will not be possible for the CAA to check and verify whether it is accurate and correct nor does the CAA undertake to do so. Consequently the CAA cannot accept any liability for any financial loss caused by the persons reliance on it. Contents Foreword Introductory Notes Full Analysis – By Reporting Airport Birmingham Edinburgh Gatwick Glasgow Heathrow London City Luton Manchester Newcastle Stansted Full Analysis With Arrival / Departure Split – By A Origin / Destination Airport B C – E F – H I – L M – N O – P Q – S T – U V – Z Summary Analysis FOREWORD 1 CONTENT 1.1 Punctuality Statistics: Heathrow, Gatwick, Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham, Luton, Stansted, Edinburgh, Newcastle and London City - Full and Summary Analysis is prepared by the Civil Aviation Authority with the co-operation of the airport operators and Airport Coordination Ltd. Their assistance is gratefully acknowledged. 2 ENQUIRIES 2.1 Statistics Enquiries concerning the information in this publication and distribution enquiries concerning orders and subscriptions should be addressed to: Civil Aviation Authority Room K4 G3 Aviation Data Unit CAA House 45/59 Kingsway London WC2B 6TE Tel. 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] 2.2 Enquiries concerning further analysis of punctuality or other UK civil aviation statistics should be addressed to: Tel: 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] Please note that we are unable to publish statistics or provide ad hoc data extracts at lower than monthly aggregate level. -

Fields Listed in Part I. Group (8)

Chile Group (1) All fields listed in part I. Group (2) 28. Recognized Medical Specializations (including, but not limited to: Anesthesiology, AUdiology, Cardiography, Cardiology, Dermatology, Embryology, Epidemiology, Forensic Medicine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oncology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiology, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Proctology, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Speech Pathology, Sports Medicine, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Toxicology, Urology and Virology) 2C. Veterinary Medicine 2D. Emergency Medicine 2E. Nuclear Medicine 2F. Geriatrics 2G. Nursing (including, but not limited to registered nurses, practical nurses, physician's receptionists and medical records clerks) 21. Dentistry 2M. Medical Cybernetics 2N. All Therapies, Prosthetics and Healing (except Medicine, Osteopathy or Osteopathic Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Chiropractic and Optometry) 20. Medical Statistics and Documentation 2P. Cancer Research 20. Medical Photography 2R. Environmental Health Group (3) All fields listed in part I. Group (4) All fields listed in part I. Group (5) All fields listed in part I. Group (6) 6A. Sociology (except Economics and including Criminology) 68. Psychology (including, but not limited to Child Psychology, Psychometrics and Psychobiology) 6C. History (including Art History) 60. Philosophy (including Humanities) -

Republic of Yemen Air Transport Sector Review Note

Report No. 49177-YE Republic of Yemen Public Disclosure Authorized Air Transport Sector Strategy Note September 2010 Middle East and North Africa Region Energy and Transport Unit Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized World Bank document Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange rate effective on March 8, 2010) Currency Unit = Yemeni Rial (YER) 1 YER = 0.0049 USD 1 USD = 205 YER Fiscal Year: January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACAC Arab Civil Aviation Commission ADE Aden International Airport AOC Air Operator Certificate ATC Air Traffic Control ATIS Automated Terminal Information System BASA Bilateral Air Service Agreements CAMA Civil Aviation and Meteorological Authority of Yemen FIR Fligths Information Region GNSS Global Navigation Satellite Systems GoY Government of Yemen GPS Global Positioning System IATA International Air Transport Association ICAO International Civil Aviation Organization ILS Instrument Landing Approach MoT Ministry of Transport RIY Al-Mukalla Airport SAH Sana’a International Airport SARP Standards and Recommended Practices UAE United Arab Emirates USOAP Universal Safety Oversight Audit Programme VOR - DME VHF Omni-Directional Radio Range - Distance Measuring Equipment 2/65 September 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY – GENERAL CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............... 4 I. THE AIR TRANSPORT SECTOR AT A GLANCE ....................................................................... 9 II. AIR TRANSPORT SERVICES AND COMPETITION POLICY..........................................10 -

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit Birmingham, Gatwick, Glasgow, Heathrow, Luton, Manchester, Stansted Full and Summary Analysis November 1995 Disclaimer The information contained in this report will be compiled from various sources and it will not be possible for the CAA to check and verify whether it is accurate and correct nor does the CAA undertake to do so. Consequently the CAA cannot accept any liability for any financial loss caused by the persons reliance on it. Contents Foreword Introductory Notes Full Analysis – By Reporting Airport Birmingham Edinburgh Gatwick Glasgow Heathrow London City Luton Manchester Newcastle Stansted Full Analysis With Arrival / Departure Split – By A Origin / Destination Airport B C – E F – H I – L M – N O – P Q – S T – U V – Z Summary Analysis FOREWORD 1 CONTENT 1.1 Punctuality Statistics: Heathrow, Gatwick, Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham, Luton, Stansted, Edinburgh, Newcastle and London City - Full and Summary Analysis is prepared by the Civil Aviation Authority with the co-operation of the airport operators and Airport Coordination Ltd. Their assistance is gratefully acknowledged. 2 ENQUIRIES 2.1 Statistics Enquiries concerning the information in this publication and distribution enquiries concerning orders and subscriptions should be addressed to: Civil Aviation Authority Room K4 G3 Aviation Data Unit CAA House 45/59 Kingsway London WC2B 6TE Tel. 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] 2.2 Enquiries concerning further analysis of punctuality or other UK civil aviation statistics should be addressed to: Tel: 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] Please note that we are unable to publish statistics or provide ad hoc data extracts at lower than monthly aggregate level. -

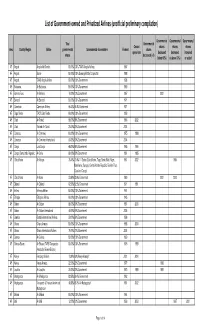

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

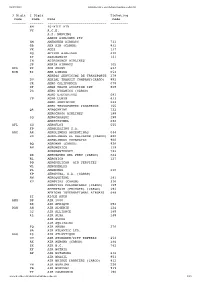

3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E

06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------- ------- ------------------------------ --------- 6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E. A.S. NORVING AARON AIRLINES PTY SM ABERDEEN AIRWAYS 731 GB ABX AIR (CARGO) 832 VX ACES 137 XQ ACTION AIRLINES 410 ZY ADALBANAIR 121 IN ADIRONDACK AIRLINES JP ADRIA AIRWAYS 165 REA RE AER ARANN 684 EIN EI AER LINGUS 053 AEREOS SERVICIOS DE TRANSPORTE 278 DU AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY(CARGO) 892 JR AERO CALIFORNIA 078 DF AERO COACH AVIATION INT 868 2G AERO DYNAMICS (CARGO) AERO EJECUTIVOS 681 YP AERO LLOYD 633 AERO SERVICIOS 243 AERO TRANSPORTES PANAMENOS 155 QA AEROCARIBE 723 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES 198 3Q AEROCHASQUI 298 AEROCOZUMEL 686 AFL SU AEROFLOT 555 FP AEROLEASING S.A. ARG AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 044 VG AEROLINEAS EL SALVADOR (CARGO) 680 AEROLINEAS URUGUAYAS 966 BQ AEROMAR (CARGO) 926 AM AEROMEXICO 139 AEROMONTERREY 722 XX AERONAVES DEL PERU (CARGO) 624 RL AERONICA 127 PO AEROPELICAN AIR SERVICES WL AEROPERLAS PL AEROPERU 210 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. (CARGO) AW AEROQUETZAL 291 XU AEROVIAS (CARGO) 316 AEROVIAS COLOMBIANAS (CARGO) 158 AFFRETAIR (PRIVATE) (CARGO) 292 AFRICAN INTERNATIONAL AIRWAYS 648 ZI AIGLE AZUR AMM DP AIR 2000 RK AIR AFRIQUE 092 DAH AH AIR ALGERIE 124 3J AIR ALLIANCE 188 4L AIR ALMA 248 AIR ALPHA AIR AQUITAINE FQ AIR ARUBA 276 9A AIR ATLANTIC LTD. AAG ES AIR ATLANTIQUE OU AIR ATONABEE/CITY EXPRESS 253 AX AIR AURORA (CARGO) 386 ZX AIR B.C. 742 KF AIR BOTNIA BP AIR BOTSWANA 636 AIR BRASIL 853 AIR BRIDGE CARRIERS (CARGO) 912 VH AIR BURKINA 226 PB AIR BURUNDI 919 TY AIR CALEDONIE 190 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 1/15 06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt SB AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 063 ACA AC AIR CANADA 014 XC AIR CARIBBEAN 918 SF AIR CHARTER AIR CHARTER (CHARTER) AIR CHARTER SYSTEMS 272 CCA CA AIR CHINA 999 CE AIR CITY S.A. -

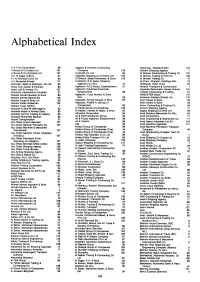

Alphabetical Index

Alphabetical Index A A Turki Corporation 88 Algeemi & Partners Contracting Alsharhan, Abdulla Sultan, 137 A Besse & Co (Aden) Ltd 161 Company 129 Alsharif Shipping Agency 7 A Besse & Co (Somalia) Ltd 107 AI Ghaith Co Ltd 84 AI Shirawi Contracting & Trading Co 137 A H AI Sagar & Bros 37 Alghalebi Shipping Co (Yemen) Ltd 155 AI Shirawi Trading & Cont Co 130 A I AI Khorayef Sons Co 83 AI Ghandi, Saeed Mohamed, & Sons 135 AI Shoala Trading Co 76 A S Derwiche Ahmad 117 AI Ghanim & AI Outub Shipping AI Thani, Ghanem, Holdings WLL 76 Abahsain, Saleh & Abdulaziz, Co Ltd 83 Agencies Co WLL 37 Altobaishi, Fahd, & Co 87 Abdul Aziz Zaidan & Partners 83 Alghanim, Ali & Fouad, Establishment 37 Alwardi Transport & Construction 7 Abdul Jalil & Henson Co 127 Alghanim Industries Corporate Alyemda Democratic Yemen Airlines 161 Abdulaziz Abdulmohsin Alrashed 37 Development 38 Ambola Contracting & Trading 67 Abdulla Ahmed Ouralshi & Sons 83 Alghanim, Yusuf Ahmad, & Sons AM EASTER Dubai 137 Abdulla Ahmed Rashid Est 146 WLL 38 American Eastern (Dubai) Ltd 137 Abdulla Fouad & Sons Co 83 Algosaibi, Ahmad Hamad, & Bros 85 Amin Kawar & Sons 29 Abdulla Sultan Alsharhan 135 Algosaibi, Khalifa A, (Group of Amin Kawar & Sons 49 Abdulla Yusuf Fakhro 7 Companies) 85 Amiry Contracting & Trading Co 40 Abdullah & Said M OBinzagrCo 83 AI Hareb Group of Companies 135 Amoun Shipping Agency 17 Abdullah Abbar & Ahmed Zainy 83 AI Hatlani, Hamad AI Naser, & Bros 85 Aqaba Shipping Co (Pv1) Ltd 29 Abdullah Est For Trading & Industry 83 Alhuselni Corporation 85 Arab Builders Mercantile -

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit Birmingham, Gatwick, Glasgow, Heathrow, Luton, Manchester, Stansted Full and Summary Analysis February 1995 Disclaimer The information contained in this report will be compiled from various sources and it will not be possible for the CAA to check and verify whether it is accurate and correct nor does the CAA undertake to do so. Consequently the CAA cannot accept any liability for any financial loss caused by the persons reliance on it. Contents Foreword Introductory Notes Full Analysis – By Reporting Airport Birmingham Edinburgh Gatwick Glasgow Heathrow London City Luton Manchester Newcastle Stansted Full Analysis With Arrival / Departure Split – By A Origin / Destination Airport B C – E F – H I – L M – N O – P Q – S T – U V – Z Summary Analysis FOREWORD 1 CONTENT 1.1 Punctuality Statistics: Heathrow, Gatwick, Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham, Luton, Stansted, Edinburgh, Newcastle and London City - Full and Summary Analysis is prepared by the Civil Aviation Authority with the co-operation of the airport operators and Airport Coordination Ltd. Their assistance is gratefully acknowledged. 2 ENQUIRIES 2.1 Statistics Enquiries concerning the information in this publication and distribution enquiries concerning orders and subscriptions should be addressed to: Civil Aviation Authority Room K4 G3 Aviation Data Unit CAA House 45/59 Kingsway London WC2B 6TE Tel. 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] 2.2 Enquiries concerning further analysis of punctuality or other UK civil aviation statistics should be addressed to: Tel: 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] Please note that we are unable to publish statistics or provide ad hoc data extracts at lower than monthly aggregate level. -

Official Journal C26? Volume 33 of the European Communities 23 °Ctober 199°

^•^ /*/*• • "1 "T" "I ISSN 0378-6986 Official Journal C26? Volume 33 of the European Communities 23 °ctober 199° English edkion Information and Notices Notice No Contents Page I Information Commission 90/C 267/01 Ecu 1 90/C 267/02 Notice pursuant to Article 19 (3) of Regulation No 17 concerning Case IV/32.659 — IATA passenger agency programme 2 Court of Justice 90/C 267/03 Judgment of the Court (First Chamber) of 3 October 1990 in Case C-61/89 (reference for a preliminary ruling made by the Cour d'Appel, Aix-en-Provence): criminal proceedings against Marc Gaston Bouchoucha (Freedom of establishment: Practice of paramedical professions (osteopathy)) 9 90/C 267/04 Case C-264/90: Reference for a preliminary ruling by the Finanzgericht Hamburg by order of that court of 12 July 1980 in the Case of Heinrich Wehrs v. Haupt- zollamt Liineburg 9 90/C 267/05 Case C-290/90: Action brought on 20 September 1990 by the Commission of the European Communities against the Federal Republic of Germany 9 90/C 267/06 Case C-291/90: Action brought on 21 September 1990 by the Portuguese Republic against the Council of the European Communities 10 II Preparatory Acts Commission 90/C 267/07 Proposal for a Council Regulation (EEC) on the introduction and the maintenance of agricultural production methods compatible with the requirements of the protection of the environment and the maintenance of the countryside 11 1 (Continued overleaf) Notice No Contents (continued) Page 90/C 267/08 Modification of the draft Financial Regulation applicable to development finance cooperation under the Fourth Lome Convention 14 90/C 267/09 Proposal for a Council Directive amending Directive 89/396/EEC on indications or marks identifying the lot to which a foodstuff belongs 15 III Notices Commission 90/C 267/10 Outcome of the invitations to tender (Community food aid) 16 23. -

Sea Sampling

, ONS, \ ~ . 1 Drummond Gate, London SWI V 2QQ. XY INTERNATIONAL PASSENGER SURVEY INTERNATIONAL PASSENGER SURVEY L SEA SAMPLING 2ND QUARTER 1997 L DATE OF INTERVIEW ON SHORT-HAUL SEA CROSSINGS : The contact may be interviewed on a night crossing on a different date from when the boat sailed. Departures : code the date the ship sailed from UK dock. Arrivals : code the date the ship will arrive at UK dock. L DOVER - CALAIS CROSSINGS ROUTES lA-lM SAMPLING DAYS STENA LINE EASTERN DOCKS 2nd QUARTER 1997 ALL TIMES LOCAL SAMPLING INTERVAL 1 in 10 France is one hour ahead of that in the UK during this quarter. APPROXIMATE CROSSING TIME 1 HOUR 30 MINS ROUTE DATE OUT IN L APRIL 60\ 1BB FRIDAY 4th 05.00 08.30 boa lE MONDAY 21st 11.15 14.30 6.3 1(2 WEDNESDAY 23rd 08.15 11.30 @ 0+ 1KK SUNDAY 27th 21.45 01.00 (Men 28th) MAY MONDAY 5th 17.15 20.30 WEDNESDAY 7th 02.30 06.30 SATURDAY 10th 18.45 22.00 14.15 13 08 lG THURSDAY 15th 17.30 ~oq 1BO TUESDAY 27th 06.45 10.00 L JUNE L\o lH SATURDAY 7th 15.45 19.00 bll 1DD TUESDAY 10th 09.45 13.00 bla lK THURSDAY 12th 20.15 *23.30 6!3 lC FRIDAY 20th 08.15 11.30 (gl& lF SUNDAY 29th 12.45 16.00 * Due to arrive Dover the following day. DOVER - CALAIS CROSSINGS ROUTES lN-lZ SAMPLING DAYS P&O EUROPEAN FERRIES d EASTERN DOCKS 2nd QUARTER 1997 ALL TIMES LOCAL SAMPLING INTERVAL 1 in 10 France is one hour ahead of that in the UK during this quarter. -

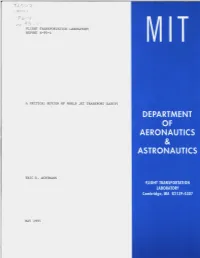

Flight Transportation Laboratory Report R-95-4 A

FLIGHT TRANSPORTATION LABORATORY REPORT R-95-4 A CRITICAL REVIEW OF WORLD JET TRANSPORT SAFETY ERIC D. ACHTMANN MAY 1995 ARCHNJES A Critical Review of World Jet Transport Safety by Eric D. Achtmann Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics on May 1, 1995, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Aeronautics and Astronautics Abstract This thesis is intended to serve as a comprehensive introduction to world jet transport safety and aviation fire safety. Divided into six sections, this thesis contains: 1) a statistical review of overall levels of safety and risk assessment in world jet transportation, 2) a statistical breakdown of jet accidents occurring between 1970 and 1992 by accident type and cause, 3) a case review of major jet accidents involving fire, 4) a review of fire prevention and fire hardening measures in jet transport aircraft, 5) a review of fire management practices in world jet transport aviation, and 6) a comprehensive chronological summary of all world jet transport accidents occurring between 1970 and 1992. Special emphasis is placed on fire safety, as statistics have shown that both in-flight and post-crash fires are among least survivable of all accident causes and are leaders in total fatalities. Included is an exhaustive review of aviation fire-fighting agents and equipment, as well as design parameters and equipment used for the fire hardening of jet aircraft. Finally, an economic analysis is included to illustrate the economic impact of fire safety measures. Thesis Supervisor: Robert W. Simpson, Ph.D. Title: Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Director, MIT Flight Transportation Laboratory -2- Foreword This thesis is intended to shed some light on the basics of jet transport and aviation fire safety.