In-Service Teachers' Understanding And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPANION Disorientation and Depression

INSIDE Love at First A “Kneady” Cat Nevins Farm Pet Horoscopes! Sight Gets the Care Winter Page 7 Page 2 She Needs Festival —Come Page 3 Meet Santa! Page 4 Holiday Poison Control Animal Poison Control Hotline 877-2ANGELL Along with holiday and winter fun come a exaggerated, mild stomach upset could still host of hazards for pets — ingested occur if ingested. substances that can be harmful or 5. Yeast dough: If swallowed, even cause death. To help pet uncooked yeast dough can rise in caretakers deal with these the stomach and cause extreme emergencies, the Angell Animal discomfort. Pets who have eaten Medical Centers have teamed up bread dough may experience with the ASPCA’s board-certified abdominal pain, bloat, vomiting, veterinary toxicologists to offer a COMPANION disorientation and depression. unique 24-hour, seven-days-a-week Since a breakdown product of poison hotline. Help is now just a rising dough is alcohol, it can Fall/Winter 2005 phone call away. Call the also potentially cause alcohol Angell Animal Poison Control Chocolate causes indigestion. poisoning. Many yeast Hotline at 877-2ANGELL. Here ingestions require surgical removal of is a list of 10 items that you should keep the dough, and even small amounts can away from your pets this holiday season: be dangerous. 1. Chocolate: Clinical effects can 6. Table food (fatty, spicy), moldy be seen with the ingestion of Sam was in desperate need of blood due to foods, poultry bones: Poultry as little as 1/4 ounce of the severity of her condition. Luckily, Angell bones can splinter and cause baking chocolate by a is able to perform blood transfusions on-site. -

Rev. Kim K. Crawford Harvie Arlington Street Church 3 October, 2010

1 Rev. Kim K. Crawford Harvie Arlington Street Church 3 October, 2010 Love Dogs One night a man was crying, Allah! Allah! His lips grew sweet with the praising, until a cynic said, “So! I have heard you calling out, but have you ever gotten any response?” The man had no answer to that. He quit praying and fell into a confused sleep. He dreamed he saw Khidr,1 the guide of souls, in a thick, green foliage. “Why did you stop praising?” [he asked] “Because I've never heard anything back.” [Khidr, the guide of souls, spoke:] This longing you express is the return message. The grief you cry out from draws you toward union. Your pure sadness that wants help is the secret cup. Listen to the moan of a dog for its master. That whining is the connection. There are love dogs 1 possibly pronounced KY-derr 2 no one knows the names of. Give your life to be one of them.2 That's our friend Rumi, the13th century Persian Sufi mystic: Give your life to be a love dog. George Thorndike Angell was born in 1823. Perhaps because of a childhood in poverty, he had deep convictions about social change. He was already well known for his fourteen year partnership with the antislavery activist Samuel E. Sewall when, one day in March of 1868, two horses, each carrying two riders over forty miles of rough road, were raced until they both dropped dead. George Angell was appalled. He penned a letter of protest that appeared in the Boston Daily Advertiser, “where it caught the attention of Emily Appleton, a prominent Bostonian who deeply loved animals and was already nurturing the first stirrings of an American anticruelty movement. -

Anglo-American Blood Sports, 1776-1889: a Study of Changing Morals

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1974 Anglo-American blood sports, 1776-1889: a study of changing morals. Jack William Berryman University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Berryman, Jack William, "Anglo-American blood sports, 1776-1889: a study of changing morals." (1974). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1326. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1326 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLO-AMERICAN BLOOD SPORTS, I776-I8891 A STUDY OF CHANGING MORALS A Thesis Presented By Jack William Berryman Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS April, 197^ Department of History » ii ANGLO-AMERICAN BLOOD SPORTS, 1776-1889 A STUDY OF CHANGING MORALS A Thesis By Jack V/illiam Berryman Approved as to style and content by« Professor Robert McNeal (Head of Department) Professor Leonard Richards (Member) ^ Professor Paul Boyer (I'/iember) Professor Mario DePillis (Chairman) April, 197^ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Upon concluding the following thesis, the many im- portant contributions of individuals other than myself loomed large in my mind. Without the assistance of others the project would never have been completed, I am greatly indebted to Professor Guy Lewis of the Department of Physical Education at the University of Massachusetts who first aroused my interest in studying sport history and continued to motivate me to seek the an- swers why. -

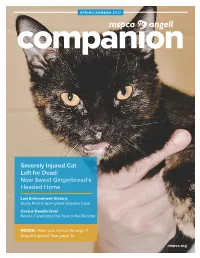

Spring/Summer 2017

SPRING/SUMMER 2017 Severely Injured Cat Left for Dead: Now Sweet Gingerbread’s Headed Home Law Enforcement Victory: Guilty Plea in Springfield Hoarder Case Cock-a-Doodle-Doo! Nevins Celebrates the Year of the Rooster INSIDE: Have you visited George T. Angell’s grave? See page 12 mspca.org Table of Contents Did You Know... Cover Story: Severely Injured Cat Left for Dead .........1 ...that the MSPCA–Angell is a Angell Animal Medical Center ............................................2 stand-alone, private, nonprofit organization? We are not Advocacy ...................................................................................3 operated by any national humane Cape Cod Adoption Center .................................................4 organization. Donations you Nevins Farm ..............................................................................5 make to “national” humane PR Corner, Events Update ....................................................6 organizations do not funnel down Boston Adoption Center .......................................................7 to the animals we serve Law Enforcement .....................................................................8 in Massachusetts. The Angell Surgeon Honored .....................................................9 MSPCA–Angell relies Donor Spotlight ......................................................................10 solely on the support of Archives Corner ..................................................................... 12 people like you who care deeply about animals. -

The State of the Animals: 2001 More Than a Slap on the Wrist

Overview: The State of Animals in 2001 Paul G. Irwin he blizzard of commentary tors have taken part in a fascinating, environments; and change their inter- marking the turn of the millen- sometimes frustrating, dialogue that actions with other animals, evolving Tnium is slowly coming to an end. seeks to balance the needs of the nat- from exploitation and harm to Assessments of the past century (and, ural world with those of the world’s respect and compassion. more ambitiously, the past millenni- most dominant species—and in the Based upon that mission, The HSUS um) have ranged from the self-con- process create a truly humane society. almost fifty years after its founding gratulatory to the condemnatory. The strains created by unrestrained in 1954, “has sought to respond cre- Written from political, technological, development and accelerating harm atively and realistically to new chal- cultural, environmental, and other to the natural world make it impera- lenges and opportunities to protect perspectives, some of these commen- tive that the new century’s under- animals” (HSUS 1991), primarily taries have provided the public with standing of the word “humane” incor- through legislative, investigative, and thoughtful, uplifting analyses. At porate the insight that our human educational means. least one commentary has concluded fate is linked inextricably to that of It is only coincidentally that the that a major issue facing the United all nonhuman animals and that we choice has been made to view the States and the world is the place and all have a duty to promote active, animal condition through thoughtful plight of animals in the twenty-first steady, thorough notions of justice analysis of the past half century—the century, positing that the last few and fair treatment to animals and life span of The HSUS—rather than of decades of the twentieth century saw nonhuman nature. -

Organized Animal Protection and the Language of Rights in America, 1865-1900

*DO NOT CITE OR DISTRIBUTE WITHOUT PERMISSION* “The Inalienable Rights of the Beasts”1: Organized Animal Protection and the Language of Rights in America, 1865-1900 Susan J. Pearson Assistant Professor, Department of History Northwestern University Telephone: 847-471-3744 1881 Sheridan Road Email: [email protected] Evanston, IL 60208 ABSTRACT Contemporary animal rights activists and legal scholars routinely charge that state animal protection statutes were enacted, not to serve the interests of animals, but rather to serve the interests of human beings in preventing immoral behavior. In this telling, laws preventing cruelty to animals are neither based on, nor do they establish, anything like rights for animals. Their raison d’etre, rather, is social control of human actions, and their function is to efficiently regulate the use of property in animals. The (critical) contemporary interpretation of the intent and function of animal cruelty laws is based on the accretion of actions – on court cases and current enforcement norms. This approach confuses the application and function of anticruelty laws with their intent and obscures the connections between the historical animal welfare movement and contemporary animal rights activism. By returning to the context in which most state anticruelty statutes were enacted – in the nineteenth century – and by considering the discourse of those activists who promoted the original legislation, my research reveals a more complicated story. Far from being concerned only with controlling the behavior of deviants, the nineteenth-century animal welfare activists who agitated for such laws situated them within a “lay discourse” of rights, borrowed from the successful abolitionist movement, that connected animal sentience, proved through portrayals of their suffering, to animal rights. -

The Power of Positive Programs in the American Humane Movement

The Power of Positive Programs in the American Humane Movement discussion papers of the National Leadership Conference of The Humane Society of the United States October 3-5, 1969 Hershey, Pennsylvania ...... �l CONTENTS Foreword .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Report of the President (Mel L. Morse) . .. .. .. 4 Report of the Treasurer (William Kerber) . .. .. .. .. .. 15 Our Challenge and Our Opportunity (Coleman Burke) ......... 18 Protection of Wildlife (Leonard Hall) . .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 Problems in Transportation of Animals (Mrs. Alice M. Wagner) ............................... 28 Humane Education Programs for Youth (Dr. Virgil S. Hollis; Sherwood Norman; Dr. Jean McClure Kelty) .............. 34 The Misuse of Animals in the Science Classroom (Prof. Richard K. Morris) ... , . .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 1 Symposium on Livestock Problems (John C. Macfarlane; Dr.F.J.Mulhern) .................................. 58 Extension of Community Programs for Animal Protection (Milton B. Learner) ......................... 68 Protection for Animals in Biomedical Research (F. L. Thomsen) .................................... 75 Cruelty for Fun (Cleveland Amory) ....................... 83 The Humane Movement and the Survival of All Living Things (Roger Caras) ........................ 89 Published by THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES Resolutions .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 95 1145 Nineteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 FOREWORD The 1969 HSUS National Leadership Conference, held in Hershey, Pa., on October 3-5, was the occasion for a critical evaluation by national leaders of the most important problems currently facing the American humane movement. The three day meeting concentrated on discussion of strategy and program aimed at progress all along the humane front. The great tasks confronting humanitarians were faced with confidence in the movement's ability to tackle them successfully. There were major speeches by recognized experts. There were panel discussions and question and answer sessions. -

Animal Symbols in Edgar Allan Poe's Stories

Animal Symbols in Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories A Tale of a Ragged Mountain, The Black Cat,Ttale - Tell Heart THESIS Nurin Aliyafi Romadhoni (10320105) ENGLISH LETTERS AND LANGUAGE DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITY THE STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2014 i Animal Symbols in Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories A Tale of a Ragged Mountain, The Black Cat,Tale - Tell Heart THESIS Presented to: State Islamic University Maulana Malik Ibrahim of Malang in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra (S1) in English Letters and Language Department Nurin Aliyafi Romadhoni (10320105) Supervisor : Ahmad Ghozi, M.A. ENGLISH LETTERS AND LANGUAGE DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITY THE STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2014 ii APPROVAL SHEET This is to certify that Nurin Aliyafi Romadhoni’s thesis entitled Animal Symbols in Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories has been approved by the thesis advisor For further approval by the Board of Examiners. Malang, 5 june 2014 Approved by Acknowledged by The Advisor, The Head of the Department of English Language and Literature, Ahmad Ghozi, M. A. Dr. Syamsuddin, M.Hum NIP. 1976911222006041001 Approved by The Dean of Faculty of Humanities Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University Malang Dr. Hj. Istiadah, M.A NIP. 19670313 1991032 2 001 iii LEGITIMATION SHEET This is to certify that Nurin Aliyafi Romadhoni’s thesis entitled Animal Symbols in Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories has been approved by the Board of Examiners as the requirement for the degree of Sarjana Sastra The Board of Examiners Signatures Andarwati, M. A. (Main Examiner) ___________ NIP. -

George Q. Cannon's Concern for Animal Welfare in Nineteenth-Century America

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 38 Issue 3 Article 4 7-1-1999 "A Plea for the Horse": George Q. Cannon's Concern for Animal Welfare in Nineteenth-Century America Aaron R. Kelson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Kelson, Aaron R. (1999) ""A Plea for the Horse": George Q. Cannon's Concern for Animal Welfare in Nineteenth-Century America," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 38 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol38/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kelson: "A Plea for the Horse": George Q. Cannon's Concern for Animal Wel george Q cannon ca 18901890C R savage photographer Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 1999 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 38, Iss. 3 [1999], Art. 4 CCA plea for the horse george Q cannons concern for animal welfare in nineteenth century america aaron R kelson taking a position somewhat unusualforunusual forpor his time president george Q cannon actively taught rerespectspectorforjorpot animals as a matter of religious principle george Q cannon 1827 1901 is remembered as a gentle and diplo- matic leader in the church of jesus christ of latter day saints never- ththelesseless he was a courageous and outspoken defender of the principles -

Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ANIMAL WELFARE Marc Bekoff Editor Greenwood Press Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ANIMAL WELFARE Edited by Marc Bekoff with Carron A. Meaney Foreword by Jane Goodall Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of animal rights and animal welfare / edited by Marc Bekoff with Carron A. Meaney ; foreword by Jane Goodall. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–29977–3 (alk. paper) 1. Animal rights—Encyclopedias. 2. Animal welfare— Encyclopedias. I. Bekoff, Marc. II. Meaney, Carron A., 1950– . HV4708.E53 1998 179'.3—dc21 97–35098 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 1998 by Marc Bekoff and Carron A. Meaney All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 97–35098 ISBN: 0–313–29977–3 First published in 1998 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Cover Acknowledgments: Photo of chickens courtesy of Joy Mench. Photo of Macaca experimentalis courtesy of Viktor Reinhardt. Photo of Lyndon B. Johnson courtesy of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library Archives. Contents Foreword by Jane Goodall vii Preface xi Introduction xiii Chronology xvii The Encyclopedia 1 Appendix: Resources on Animal Welfare and Humane Education 383 Sources 407 Index 415 About the Editors and Contributors 437 Foreword It is an honor for me to contribute a foreword to this unique, informative, and exciting volume. -

Humane Education Past, Present, and Future 3CHAPTER

Humane Education Past, Present, and Future 3CHAPTER Bernard Unti and Bill DeRosa Introduction rom the earliest years of orga- need to correct children’s cruelty. tance of a virtuous citizenry devoted nized animal protection in “This tendency should be watched in to republican principles of gover- FNorth America, humane educa- them, and, if they incline to any such nance. This made education of the tion—the attempt to inculcate the cruelty, they should be taught the boy especially critical, since as a man kindness-to-animals ethic through contrary usage,” Locke wrote. “For he would assume authority over fami- formal or informal instruction of chil- the custom of tormenting and killing ly, chattel, property, and social insti- dren—has been cast as a fruitful other animals will, by degrees, harden tutions. Responsibility for educating response to the challenge of reducing their hearts even toward men; and the child for his leadership role rested the abuse and neglect of animals. Yet, they who delight in the suffering and with women, who were assumed to be almost 140 years after the move- destruction of inferior creatures, will the repositories of gentle virtue, com- ment’s formation, humane education not be apt to be very compassionate passionate feeling, and devotion— remains largely the province of local or benign to those of their own kind” buffers against the heartless struggle societies for the prevention of cruelty (Locke 1989). of the masculine public sphere. and their educational divisions—if Over time Locke’s insight raised Humane education provided one they have such divisions. Efforts to interest in the beneficial moral effect means of insulating boys against the institutionalize the teaching of of childhood instruction favoring the tyrannical tendencies that might humane treatment of animals within kindly treatment of animals. -

State of Animals Ch 04

From Pets to Companion Animals 4CHAPTER Researched by Martha C. Armstrong, Susan Tomasello, and Christyna Hunter A Brief History of Shelters and Pounds nimal shelters in most U.S. their destiny: death by starvation, harassed working horses, pedestrians, communities bear little trace injury, gassing, or drowning. There and shopkeepers, but also spread ra- A of their historical British were no adoption, or rehoming, pro- bies and other zoonotic diseases. roots. Early settlers, most from the grams and owners reclaimed few In outlying areas, unchecked breed- British Isles, brought with them the strays. And while early humanitarians, ing of farm dogs and abandonment of English concepts of towns and town like Henry Bergh, founder of the city dwellers’ unwanted pets created management, including the rules on American Society for the Prevention packs of marauding dogs, which keeping livestock. Each New England of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), and killed wildlife and livestock and posed town, for example, had a common, a George Thorndike Angell, founder of significant health risks to humans central grassy area to be used by all the Massachusetts Society for the and other animals. townspeople in any manner of bene- Prevention of Cruelty to Animals State and local governments were fit, including the grazing of livestock. (MSPCA), were concerned about ani- forced to pass laws requiring dog As long as the livestock remained on mal abuse, their focus was more on owners to control their animals. Al- the common, the animals could graze working animals—horses, in particu- though laws that prohibited deliber- at will, but once the animal strayed lar—than on the fate of stray dogs.