Embodied Sovereignty: Dialogues with Contemporary Aboriginal Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eliot Feld Ballet Schedules Three Concerts the Feld Ballet, Which Will Close out Its Highly Successful New York Season Oct

William and Mary NEWS Volume XI, Number 7 ' Noii-Profit Organization Tuesday, October 19,1982 U.S. Postage PAID at WflliaaMburg, Va. Permit No. 26 College to Honor Six Alumni at Homecoming Six members of the Society of the member and former secretary of the Alumni will receive the Alumni Medallion President's Council and a member of the at Homecoming on Nov. 5-6 in recogni¬ Lord Chamberlain Society of the Virginia tion of their service to the College, Shakespeare Festival. In 1976, she and community and nation. her husband established the Sheridan- The recipients are Dr. Edward E. Kinnamon Scholarship at the College. Brickell, Jr. '50, former rector of the Muscarelle, who is chairman of the College and superintendent of Virginia board of one of the nation's largest Beach, Va. Schools; Chester F. Giermak building firms, has been honored many '50, Erie, Pa.; president and chief execu¬ times for his charitable and civic contribu¬ tive officer, Eriez Magnetics Company; tions which include the Joseph L. Mus1- Jeanne S. Kinnamon '39, Williamsburg, a carelle Center for Building Construction member of the Board of Visitors and a Studies at Farleigh Dickinson University in generous benefactor of the College; New Jersey. Among his awards is the Joseph L. Muscarelle '27, Hackensack, Pope John Paul II Humanitarian Award N.J., chairman of the Board of Joseph L. from Seton Hall University. Muscarelle has Muscarelle, Inc., and the prime benefactor been a member of the Order of the White of the Joseph L. and Margaret Muscarelle Jacket since 1977. Museum of Art now under construction at Dr. -

The BALLET RUSSE De Monte Carlo

The RECORD SHOP Phil Hart, Mgr. presents The BALLET RUSSE de Monte Carlo IN THE PORTLAND AUDITORIUM Thursday, November 16,1944 AT 8:30 P. M. * PLEASE NOTE the following cast changes, due to a leg injury sustained by MR. FRANKLIN. In Le Bourgeois Gentilhornrne Cleonte M. Nicholas MAGALLANES In Gaite Parisienne Tbe Baron M. Nihita TALIN In Danses Concertantes Leon DANIELIAN in place of Frederic FRANKLIN In Rodeo Tbe Champion Roper Mr. Herbert BLISS PROGRAM II. A • "*j 3 • ,. y LE BOURGEOIS GENTILHOMME Choreography by George Balanchine Music by Richard Strauss Scenery and costumes by Eugene Berman Scenery executed by E. B. Dunkel Studios Costumes executed by Karinska, Inc. SERENADE This ballet depicts one episode from Moliere's immortal farce, "Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme." A young man, Cleonte, is in love with M. Jourdain's daughter, Luetic M. Jourdain disapproves of the match, as Cleonte is not of noble birth and it is M. Choreography by George BALANCHINE Music by P. I. Tschaikowsky Jourdain's lifetime ambition to shed his middle-class status and rise to aristocracy. Cleonte and his valet, Coviel, impersonate respectively the son of the Great Turk and his ambassador, and under this disguise Cleonte asks for the hand of Lucile. Lucile, at first, unaware of Cleonte's disguise, bitterly resents the wedlock and not Costumes by Jean LURCAT Costumes executed by H. MAHIEU, Inc. until Cleonte raises his mask does she willingly consent. In exchange for the hand of his bride, Cleonte makes M. Jourdain a Mamamouchi—a great dignitary of Turkey—"than which there is nothing more noble in the world," by means of an imposing ceremony. -

Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE)

OKLAHOMA INDIAN TRIBE EDUCATION GUIDE Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE) Tribe: Peoria Tribe of Indians (pee-awr-ee -uh) Tribal website(s): http//www.peoriatribe.com 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” Original Homeland - The Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma is a confederation of Kaskaskia, Peoria, Piankeshaw and Wea Indians united into a single tribe in 1854. The tribes which constitute The Confederated Peorias, as they then were called, originated in the lands bordering the Great Lakes and drained by the mighty Mississippi. They are Illinois or Illini Indians, descendants of those who created the great mound civilizations in the central United States two thousand to three thousand years ago. The increased pressure from white settlers in the 1840’s and 1850’s in Kansas brought cooperation among the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Piankashaw and Wea Tribes to protect these holdings. By the Treaty of May 30, 1854, 10 Stat. 1082, the United States recognized the cooperation and consented to their formal union as the Confederated Peoria. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Ballets Russes Press

A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE THEY CAME. THEY DANCED. OUR WORLD WAS NEVER THE SAME. BALLETS RUSSES a film by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller Unearthing a treasure trove of archival footage, filmmakers Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine have fashioned a dazzlingly entrancing ode to the rev- olutionary twentieth-century dance troupe known as the Ballets Russes. What began as a group of Russian refugees who never danced in Russia became not one but two rival dance troupes who fought the infamous “ballet battles” that consumed London society before World War II. BALLETS RUSSES maps the company’s Diaghilev-era beginnings in turn- of-the-century Paris—when artists such as Nijinsky, Balanchine, Picasso, Miró, Matisse, and Stravinsky united in an unparalleled collaboration—to its halcyon days of the 1930s and ’40s, when the Ballets Russes toured America, astonishing audiences schooled in vaudeville with artistry never before seen, to its demise in the 1950s and ’60s when rising costs, rock- eting egos, outside competition, and internal mismanagement ultimately brought this revered company to its knees. Directed with consummate invention and infused with juicy anecdotal interviews from many of the company’s glamorous stars, BALLETS RUSSES treats modern audiences to a rare glimpse of the singularly remarkable merger of Russian, American, European, and Latin American dancers, choreographers, composers, and designers that transformed the face of ballet for generations to come. — Sundance Film Festival 2005 FILMMAKERS’ STATEMENT AND PRODUCTION NOTES In January 2000, our Co-Producers, Robert Hawk and Douglas Blair Turnbaugh, came to us with the idea of filming what they described as a once-in-a-lifetime event. -

COMPTES RENDUS the Life and Times of Dalton Camp

James Ferrabee COMPTES RENDUS The life and times of Dalton Camp Geoffrey Stevens, The Player: The Life and Times of Dalton Camp, Toronto, Key Porter Books, 2003. Review by James Ferrabee n the mid-1950s there was little dian politics on the provincial and For the next 30 years he was an observ- hope a Conservative Government federal scene. er rather than a participant, turning to I would or could be elected in In all, Camp watched over and writing columns for the Toronto Star Ottawa. By 1955, the Liberals had directed 28 elections. His helped create and participating in debates about pol- ruled with little effective opposition and fertilize several Tory dynasties on itics on TV, radio and in public debates. for 20 years. It felt like 40 years. Who the provincial scene, including Robert He was, in short, “a player” which is was going to stop them? Stanfield’s in Nova Scotia (11 years), also the title of Geoffrey Stevens superbly At universities, Canadian history Richard Hatfield’s in New Brunswick (16 researched and cogently written biogra- texts read like a slightly revised ver- years), William Davis’ in Ontario (14 phy of Camp. Not everyone, including sion of the history of the Liberal Party. years) and Duff Roblin’s in Manitoba (11 many who were deeply involved in poli- No one found that strange. The pre- years). He helped direct John Diefenbak- tics in the 1960s and 1970s, will want to eminent historian was A.R.M. Lower er’s campaigns in 1957, 1958, 1962 and read it. -

Miguel Terekhov Collection

Miguel Terekhov Collection Inventory Prepared by Jessie Hopper Last Revision - June 2013 Table of Contents Collection Summary.............................................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Scope and Content Note....................................................................................................... 1 Organization of the Miguel Terekhov Collection................................................................ 2 Restrictions........................................................................................................................... 2 Index Terms............................................................................................................................ 2 Administrative Information.................................................................................................... 3 Detailed Description of the Collection................................................................................. 4 Ballets Russes Archives at the University of Oklahoma School of Dance Collection Summary Repository Ballets Russes Archives at the University of Oklahoma School of Dance Collection Miguel Terekhov Title Miguel Terekhov Collection Dates 1928-2012 Bulk 1935-1997 Dates Quantity 8 boxes, 5 linear feet Abstract Miguel Terekhov, a Uruguayan dancer, was a member of both de Basil's Original Ballet Russe and the Ballet Russe de -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

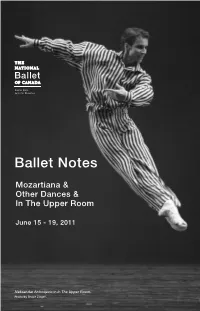

Ballet Notes

Ballet Notes Mozartiana & Other Dances & In The Upper Room June 15 - 19, 2011 Aleksandar Antonijevic in In The Upper Room. Photo by Bruce Zinger. Orchestra Violins Bassoons Benjamin BoWman Stephen Mosher, Principal Concertmaster JerrY Robinson LYnn KUo, EliZabeth GoWen, Assistant Concertmaster Contra Bassoon DominiqUe Laplante, Horns Principal Second Violin Celia Franca, C.C., Founder GarY Pattison, Principal James AYlesWorth Vincent Barbee Jennie Baccante George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Derek Conrod Csaba KocZó Scott WeVers Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Sheldon Grabke Artistic Director Executive Director Xiao Grabke Trumpets David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. NancY KershaW Richard Sandals, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk Mark Dharmaratnam Principal Conductor YakoV Lerner Rob WeYmoUth Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer JaYne Maddison Trombones Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Ron Mah DaVid Archer, Principal YOU dance / Ballet Master AYa MiYagaWa Robert FergUson WendY Rogers Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne DaVid Pell, Bass Trombone Filip TomoV Senior Ballet Master Richardson Tuba Senior Ballet Mistress Joanna ZabroWarna PaUl ZeVenhUiZen Sasha Johnson Aleksandar AntonijeVic, GUillaUme Côté*, Violas Harp Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, LUcie Parent, Principal Zdenek KonValina, Heather Ogden, Angela RUdden, Principal Sonia RodrigUeZ, Piotr StancZYk, Xiao Nan YU, Theresa RUdolph KocZó, Timpany Bridgett Zehr Assistant Principal Michael PerrY, Principal Valerie KUinka Kevin D. Bowles, Lorna Geddes, -

News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol

NEWS FROM THE JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 6, NO. 1 (2019) The Jerome Robbins Dance Division: 75 Years of Innovation and Advocacy for Dance by Arlene Yu, Collections Manager, Jerome Robbins Dance Division Scenario for Salvatore Taglioni's Atlanta ed Ippomene in Balli di Salvatore Taglioni, 1814–65. Isadora Duncan, 1915–18. Photo by Arnold Genthe. Black Fiddler: Prejudice and the Negro, aired on ABC-TV on August 7, 1969. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, “backstage.” With this issue, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Jerome Robbins History Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. In 1944, an enterprising young librarian at The New York Public Library named One of New York City’s great cultural treasures, it is the largest and Genevieve Oswald was asked to manage a small collection of dance materials most diverse dance archive in the world. It offers the public free access in the Music Division. By 1947, her title had officially changed to Curator and the to dance history through its letters, manuscripts, books, periodicals, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, known simply as the Dance Collection for many prints, photographs, videos, films, oral history recordings, programs and years, has since grown to include tens of thousands of books; tens of thousands clippings. It offers a wide variety of programs and exhibitions through- of reels of moving image materials, original performance documentations, audio, out the year. Additionally, through its Dance Education Coordinator, it and oral histories; hundreds of thousands of loose photographs and negatives; reaches many in public and private schools and the branch libraries. -

NATIVE AMERICAN CONNECTIONS at JACOB's PILLOW a Summary Of

NATIONAL MEDAL OF ARTS | NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NATIVE AMERICAN CONNECTIONS AT JACOB’S PILLOW A summary of the intersections between the Pillow and Indigenous peoples and traditions of the Americas, compiled by Jacob’s Pillow Director of Preservation Norton Owen. According to the chapter titled “Indians in Becket” by Pillow neighbor Ruth I. Derby in A Bicentennial History of Becket, the Mohicans camped in Becket during the summer months, hunting moose, deer, and bear, as well as otter, raccoons, beaver, foxes, and other small fur-bearing animals. A later Becket history identified descendants of the Muckhaneek, Narragansett, and Pequot tribes. They collected and dried food for the winter and skins for clothing. They also made maple syrup and sugar and taught settlers to do this. They sold the land to settlers in 1736, though the plans weren’t accurate and Chief Konkapot was upset that traditional hunting grounds were inadvertently included in the property transfer. This discrepancy was later settled with an additional payment that covered all lands west of the Westfield River. There are reportedly Indian burial grounds off George Carter Road, near Jacob’s Pillow. 1933 – During its first summer of Pillow performances, the repertory of Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers includes the Osage-Pawnee Dance of Greeting and a Shawn solo, Invocation to the Thunderbird. 1934 – Ted Shawn revives his Hopi Indian Eagle Dance, originally part of his full-length 1923 production, Feather of the Dawn. A new group work, Ponca Indian Dance, is presented for the first time. 1936 – The first act of a full-evening work, O Libertad!, opens with a section titled Noche Triste de Moctezuma and also includes other sections about Native Americans of the Southwest. -

B Y S U S a N D R a G

NATIVE AMERICANS AND WESTERN ICONS HAVE BEEN THE TWIN PILLARS OF OKLAHOMA’S CULTURE SINCE WELL BEFORE STATEHOOD. WE ASSEMBLED TWO PANELS OF EXPERTS TO DETERMINE WHICH BRAVE, HARDWORKING, JUSTICE-SEEKING, FRONTIER-TAMING INDIVIDUALS DESERVE A PLACE IN OKLAHOMA’S WESTERN PANTHEON. THE RESULT IS THE FOLLOWING LIST OF THE MOST INFLUENTIAL NATIVE AMERICANS, COWBOYS, AND COWGIRLS IN THE STATE’S HISTORY. BY SUSAN DRAGOO OklahomaToday.com 41 BILL ANOATUBBY BEUTLER FAMILY (b. 1945) Their stock was considered a CHICKASAW NATION CHICKASAW Bill Anoatubby grew up in Tisho- cowboy’s nightmare, but that mingo and first went to work was high praise for the Elk City- for the Chickasaw Nation as its RANDY BEUTLER COLLECTION based Beutler Brothers—Elra health services director in 1975. (1896-1987), Jake (1903-1975), He was elected governor of the and Lynn (1905-1999)—who Chickasaws in 1987 and now is in 1929 founded a livestock in his eighth term and twenty-ninth year in that office. He has contracting company that became one of the world’s largest worked to strengthen the nation’s foundation by diversifying rodeo producers. The Beutlers had an eye for bad bulls and its economy, leading the tribe into the twenty-first century as a tough broncs; one of their most famous animals, a bull politically and economically stable entity. The nation’s success named Speck, was successfully ridden only five times in more has brought prosperity: Every Chickasaw can access education than a hundred tries. The Beutler legacy lives on in a Roger benefits, scholarships, and health care.