LOGOS Volume 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuba and the World.Book

CUBA FUTURES: CUBA AND THE WORLD Edited by M. Font Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies Presented at the international symposium “Cuba Futures: Past and Present,” organized by the The Cuba Project Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies The Graduate Center/CUNY, March 31–April 2, 2011 CUBA FUTURES: CUBA AND THE WORLD Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies www.cubasymposium.org www.bildner.org Table of Contents Preface v Cuba: Definiendo estrategias de política exterior en un mundo cambiante (2001- 2011) Carlos Alzugaray Treto 1 Opening the Door to Cuba by Reinventing Guantánamo: Creating a Cuba-US Bio- fuel Production Capability in Guantánamo J.R. Paron and Maria Aristigueta 47 Habana-Miami: puentes sobre aguas turbulentas Alfredo Prieto 93 From Dreaming in Havana to Gambling in Las Vegas: The Evolution of Cuban Diasporic Culture Eliana Rivero 123 Remembering the Cuban Revolution: North Americans in Cuba in the 1960s David Strug 161 Cuba's Export of Revolution: Guerilla Uprisings and Their Detractors Jonathan C. Brown 177 Preface The dynamics of contemporary Cuba—the politics, culture, economy, and the people—were the focus of the three-day international symposium, Cuba Futures: Past and Present (organized by the Bildner Center at The Graduate Center, CUNY). As one of the largest and most dynamic conferences on Cuba to date, the Cuba Futures symposium drew the attention of specialists from all parts of the world. Nearly 600 individuals attended the 57 panels and plenary sessions over the course of three days. Over 240 panelists from the US, Cuba, Britain, Spain, Germany, France, Canada, and other countries combined perspectives from various fields including social sciences, economics, arts and humanities. -

AS/Jur (2019) 50 11 December 2019 Ajdoc50 2019

Declassified AS/Jur (2019) 50 11 December 2019 ajdoc50 2019 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Abolition of the death penalty in Council of Europe member and observer states,1 Belarus and countries whose parliaments have co-operation status2 – situation report Revised information note General rapporteur: Mr Titus CORLĂŢEAN, Romania, Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group 1. Introduction 1. Having been appointed general rapporteur on the abolition of the death penalty at the Committee meeting of 13 December 2018, I have had the honour to continue the outstanding work done by Mr Yves Cruchten (Luxemburg, SOC), Ms Meritxell Mateu Pi (Andorra, ALDE), Ms Marietta Karamanli (France, SOC), Ms Marina Schuster (Germany, ALDE), and, before her, Ms Renate Wohlwend (Liechtenstein, EPP/CD).3 2. This document updates the previous information note with regard to the development of the situation since October 2018, which was considered at the Committee meeting in Strasbourg on 10 October 2018. 3. This note will first of all provide a brief overview of the international and European legal framework, and then highlight the current situation in states that have abolished the death penalty only for ordinary crimes, those that provide for the death penalty in their legislation but do not implement it and those that actually do apply it. It refers solely to Council of Europe member states (the Russian Federation), observer states (United States, Japan and Israel), states whose parliaments hold “partner for democracy” status, Kazakhstan4 and Belarus, a country which would like to have closer links with the Council of Europe. Since March 2012, the Parliamentary Assembly’s general rapporteurs have issued public statements relating to executions and death sentences in these states or have proposed that the Committee adopt statements condemning capital punishment as inhuman and degrading. -

VADP 2015 Annual Report Accomplishments in 2015

2015 Annual Report Working to End the Death Penalty through Education, Organizing and Advocacy for 24 years VADP Executive Directors, Past and Present From left: Beth Panilaitis (2008 -2010), Steve Northup (2011 -2014), Jack Payden -Travers (2002 -2007), and Michael Stone (2015). Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty P.O. Box 12222 Richmond, VA 23241 (434) 960 -7779 [email protected] www.vadp.org Message from the VADP Board President Dear VADP Supporter, resources to band together the various groups and Last year was a time of strong forward movement individuals who oppose the death penalty, for VADP. In January, we hired Michael Stone, whatever their reasons, into a cohesive force. our first full time executive director in four years, I would like to thank those of you who made a and that led to the implementation of bold new monetary donation to VADP in 2015. But our strategies and expanded programs. work is not done. So I ask you to increase your In 2015 we learned what can be accomplished in support in 2016 and to help us find others to join today’s politics when groups with different overall this important movement. And, if you are not yet purposes decide to work together on a specific a supporter of VADP, now is the time to join our shared objective — such as vital work to end the death penalty in Virginia, death penalty abolition. That, once and for all. happily, is starting to occur. Sincerely, As an example, nationally and Kent Willis in Virginia activists from every Board President point on the political spectrum are joining an extraordinary new movement to re -examine The Death Penalty in Virginia how we waste tax dollars on our expensive and ineffective criminal justice system, including ♦ Virginia has executed 111 men and women capital punishment. -

Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission

The Report of the The Report Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission Review Penalty Oklahoma Death The Report of the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission OKDeathPenaltyReview.org The Report of the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission The Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission is an initiative of The Constitution Project®, which sponsors independent, bipartisan committees to address a variety of important constitutional issues and to produce consensus reports and recommendations. The views and conclusions expressed in these reports, statements, and other material do not necessarily reflect the views of members of its Board of Directors or its staff. For information about this report, or any other work of The Constitution Project, please visit our website at www. constitutionproject.org or e-mail us at [email protected]. Copyright © March 2017 by The Constitution Project ®. All rights reserved. No part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of The Constitution Project. Book design by Keane Design & Communications, Inc/keanedesign.com. Table of Contents Letter from the Co-Chairs .........................................................................................................................................i The Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission ..............................................................................iii Executive Summary................................................................................................................................................. -

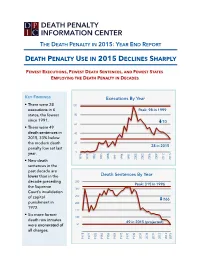

Year End Report

THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT DEATH PENALTY USE IN 2015 DECLINES SHARPLY FEWEST EXECUTIONS, FEWEST DEATH SENTENCES, AND FEWEST STATES EMPLOYING THE DEATH PENALTY IN DECADES KEY FINDINGS Executions By Year • There were 28 100 executions in 6 Peak: 98 in 1999 states, the fewest 80 since 1991. ⬇70 60 • There were 49 death sentences in 40 2015, 33% below the modern death 20 28 in 2015 penalty low set last year. 0 • New death 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 sentences in the past decade are lower than in the Death Sentences By Year decade preceding 350 Peak: 315 in 1996 the Supreme 300 Court’s invalidation of capital 250 ⬇266 punishment in 200 1972. 150 • Six more former 100 death row inmates 49 in 2015 (projected) were exonerated of 50 all charges. 1974 1977 1980 1983 1986 1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2015 THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT U.S. DEATH PENALTY DECLINE ACCELERATES IN 2015 By all measures, use of and support for the death penalty Executions by continued its steady decline in the United States in 2015. The 2015 2014 State number of new death sentences imposed in the U.S. fell sharply from already historic lows, executions dropped to Texas 13 10 their lowest levels in 24 years, and public opinion polls revealed that a majority of Americans preferred life without Missouri 6 10 parole to the death penalty. Opposition to capital punishment polled higher than any time since 1972. -

The Struggle for Democratic Environmental Governance Around

The struggle for democratic environmental governance around energy projects in post-communist countries: the role of civil society groups and multilateral development banks by Alda Kokallaj A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014 Alda Kokallaj Abstract This dissertation focuses on the struggle for democratic environmental governance around energy projects in post-communist countries. What do conflicts over environmental implications of these projects and inclusiveness reveal about the prospects for democratic environmental governance in this region? This work is centred on two case studies, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline and the Vlora Industrial and Energy Park. These are large energy projects supported by the governments of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Albania, and by powerful international players such as oil businesses, multilateral development banks (MDBs), the European Union and the United States. Analysis of these cases is based on interviews with representatives of these actors and civil society groups, narratives by investigative journalists, as well as the relevant academic literature. I argue that the environmental governance of energy projects in the post-communist context is conditioned by the interplay of actors with divergent visions about what constitutes progressive development. Those actors initiating energy projects are shown to generally have the upper hand in defining environmental governance outcomes which align with their material interests. However, the cases also reveal that the interaction between civil society and MDBs creates opportunities for society at large, and for non-government organizations who seek to represent them, to have a greater say in governance outcomes – even to the point of stopping some elements of proposed projects. -

G E N E R a L R E S U L

Analysis of the 2012 Maryland General Elections Item Type Report Authors University of Maryland, Baltimore. Office of Government & Community Affairs Publication Date 2012-11 Keywords Analysis; Elections--United States--Maryland Download date 02/10/2021 05:30:58 Item License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10713/4670 G E N ANALYSIS E OF THE R 2012 MARYLAND GENERAL ELECTIONS A L OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT AND COMMUNITY AFFAIRS R HTTP://WWW.UMARYLAND.EDU/OFFICES/GOVERNMENT/ E BALTIMORE: 620 WEST LEXINGTON STREET, FIRST FLOOR ANNAPOLIS: 60 WEST STREET, SUITE 220 S U NOVEMBER 2012 L T S UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, BALTIMORE Analysis of 2012 Maryland General Elections This summary report reflects the unofficial results of the November 6, 2012 general election for public office and statewide ballot issues in Maryland. Election results will be certified as final by the Maryland Board of State Canvassers on December 11, 2012. Results can be verified at the Maryland State Board of Elections. President of the United States Barack Obama and Joe Biden were re‐elected by popular and electoral vote as the President and Vice President, respectively. According to the Maryland State Board of Elections (unofficial results), the Obama/Biden ticket received 61.4% of the popular vote in Maryland, excluding absentee and provisional ballot results. On December 17, 2012, Maryland’s Electoral College delegates will officially cast their votes. Maryland has ten Electoral College delegates. Delegates typically cast their vote in conformance with the popular vote, but several states do not require delegates to do so. -

Visual Culture and Us-Cuban Relations, 1945-2000

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-10-2010 INTIMATE ENEMIES: VISUAL CULTURE AND U.S.-CUBAN RELATIONS, 1945-2000 Blair Woodard Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Woodard, Blair. "INTIMATE ENEMIES: VISUAL CULTURE AND U.S.-CUBAN RELATIONS, 1945-2000." (2010). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/87 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTIMATE ENEMIES: VISUAL CULTURE AND U.S.-CUBAN RELATIONS, 1945-2000 BY BLAIR DEWITT WOODARD B.A., History, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1992 M.A., Latin American Studies, University of New Mexico, 2001 M.C.R.P., Planning, University of New Mexico, 2001 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2010 © 2010, Blair D. Woodard iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writing of my dissertation has given me the opportunity to meet and work with a multitude of people to whom I owe a debt of gratitude while completing this journey. First and foremost, I wish to thank the members of my committee Linda Hall, Ferenc Szasz, Jason Scott Smith, and Alyosha Goldstein. All of my committee members have provided me with countless insights, continuous support, and encouragement throughout the writing of this dissertation and my time at the University of New Mexico. -

Death Penalty System Is Unconstitutional

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 ERNEST DEWAYNE JONES, ) 11 ) Case No.: CV 09-02158-CJC Petitioner, ) 12 ) vs. ) 13 ) ) ORDER DECLARING 14 KEVIN CHAPPELL, Warden of ) CALIFORNIA’S DEATH PENALTY California State Prison at San Quentin, ) SYSTEM UNCONSTITUTIONAL 15 ) AND VACATING PETITIONER’S Respondent. ) DEATH SENTENCE 16 ) ) 17 ) 18 19 20 On April 7, 1995, Petitioner Ernest Dewayne Jones was condemned to death by the 21 State of California. Nearly two decades later, Mr. Jones remains on California’s Death 22 Row, awaiting his execution, but with complete uncertainty as to when, or even whether, 23 it will ever come. Mr. Jones is not alone. Since 1978, when the current death penalty 24 system was adopted by California voters, over 900 people have been sentenced to death 25 for their crimes. Of them, only 13 have been executed. For the rest, the dysfunctional 26 administration of California’s death penalty system has resulted, and will continue to 27 result, in an inordinate and unpredictable period of delay preceding their actual execution. 28 Indeed, for most, systemic delay has made their execution so unlikely that the death -1- 1 sentence carefully and deliberately imposed by the jury has been quietly transformed into 2 one no rational jury or legislature could ever impose: life in prison, with the remote 3 possibility of death. As for the random few for whom execution does become a reality, 4 they will have languished for so long on Death Row that their execution will serve no 5 retributive or deterrent purpose and will be arbitrary. -

1 of 4 DOCUMENTS ALFREDO PRIETO, Plaintiff, V. HAROLD C

Page 1 1 of 4 DOCUMENTS ALFREDO PRIETO, Plaintiff, v. HAROLD C. CLARKE, et al., Defendants. 1:12cv1199 (LMB/IDD) UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, ALEXANDRIA DIVISION 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 161783 November 12, 2013, Decided November 12, 2013, Filed COUNSEL: [*1] For Alfredo Prieto, Plaintiff: Abid Alfredo Prieto ("Prieto" or "plaintiff") is an inmate at Riaz Qureshi, LEAD ATTORNEY, Latham & Watkins Sussex I State Prison ("SISP") in Waverly, Virginia, LLP, Washington, DC. awaiting execution for two capital murder convictions. Like all capital offenders in Virginia, 1 plaintiff is For Harold C. Clarke, Director, A. David Robinson, confined in a separate housing unit commonly known as Deputy Director, E. Pearson, Warden, Defendants: "death row." He has been there since October 30, 2008. Richard Carson Vorhis, LEAD ATTORNEY, Office of See Defs.' Mem. in Supp. [hereinafter Defs.' Mem.], Ex. the Attorney General, Richmond, VA; Kate Elizabeth 1, ¶ 4. Dwyre, Office of the Attorney General (Richmond), Richmond, VA. 1 As of October 2013, plaintiff was one of only eight capital offenders in the state, all of whom JUDGES: Leonie M. Brinkema, United States District are housed at SISP. See Pl.'s [*2] Mem. in Supp. Judge. of Summ. J. [hereinafter Pl.'s Mem.], Ex. 19, at 75:9-10. OPINION BY: Leonie M. Brinkema Conditions on death row are more restrictive than OPINION incarceration in the general population housing units at SISP, which is a maximum-security facility. The former amount to a form of solitary confinement: On average, MEMORANDUM OPINION plaintiff must remain in his single cell for all but one hour of the day. -

Eighth Amendment Concerns in Warner V. Gross

OCULREV Spring 2016 Willey Macro 83--117 (Do Not Delete) 6/2/2016 5:31 PM CHALLENGES TO THE “KILLING STATE”: EIGHTH AMENDMENT CONCERNS IN WARNER V. GROSS Sarah Willey* I. INTRODUCTION “That today most executions in the United States are not newsworthy suggests that the killing state is taken for granted.”1 Author and Professor Austin Sarat theorizes that the law “must find ways of distinguishing state killing from the acts to which it is a supposedly just response and to kill in such a way as not to allow the condemned to become an object of pity and, in so doing, to appropriate the status of the victim.”2 Where executions were once public displays of state power, they now take place far from the public view, hiding “behind prison walls in . carefully controlled situation[s].”3 But the State cannot hide from the inevitable— there is “violence inherent in taking human life.”4 Using drugs meant for individuals with medical needs to carry out executions is a misguided effort to mask the brutality of executions by making them look serene and peaceful—like something any one of us might experience in our final moments. But executions are, in fact, nothing like that. They are brutal, * Sarah Willey is a 2017 J.D. Candidate at Oklahoma City University School of Law. She would like to thank her family for their never-ending love, support, and encouragement. She would also like to thank the editors and the members of the Oklahoma City University Law Review for all of their assistance and patience during this process. -

ENGLISH United States Mission to the OSCE

PC.DEL/1309/15 9 October 2015 Original: ENGLISH United States Mission to the OSCE Response to the Statement Regarding Executions in the United States As delivered by Ambassador Daniel B. Baer to the Permanent Council, Vienna October 8, 2015 Thank you to our colleagues from the delegations of the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland, and all those who associated themselves with the European Union's statement for raising their concerns. As they noted, on October 6, the State of Texas executed Juan Martin Garcia for the 1998 murder of Hugo Solano. On October 1, the Commonwealth of Virginia executed Alfredo Prieto for the rape and murder of Rachael Raver and the killing of her boyfriend, Warren Fulton III, in 1988. On September 29, the State of Georgia executed Kelly Renee Gissendaner for orchestrating the murder of her husband, Douglas Gissendaner, in 1997. The United States recognizes the debate on the death penalty both within and among nations. In our closing statement, as was already mentioned, at the 2015 Human Dimension Implementation Meeting, we committed to inviting a non-governmental participant in that debate in our country to come to Vienna and share perspectives on this issue. We respect the views of our friends around this table. We remind colleagues that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which the United States is a party, provides for imposition of the death penalty for the most serious crimes when carried out pursuant to a final judgment rendered by a competent court, and accompanied by appropriate procedural safeguards and the observance of due process.